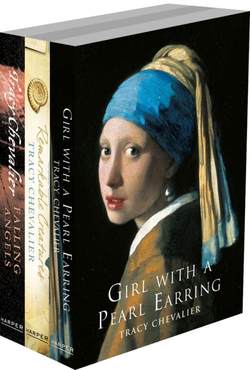

Читать книгу Tracy Chevalier 3-Book Collection: Girl With a Pearl Earring, Remarkable Creatures, Falling Angels - Tracy Chevalier - Страница 10

1666

Оглавление‘You smell of linseed oil.’

My father spoke in a baffled tone. He did not believe that simply cleaning a painter's studio would make the smell linger on my clothes, my skin, my hair. He was right. It was as if he guessed that I now slept with the oil in my room, that I sat for hours being painted and absorbing the scent. He guessed and yet he could not say. His blindness took away his confidence so that he did not trust the thoughts in his mind.

A year before I might have tried to help him, suggest what he was thinking, humour him into speaking his mind. Now, however, I simply watched him struggle silently, like a beetle that has fallen on to its back and cannot turn itself over.

My mother had also guessed, though she did not know what she had guessed. Sometimes I could not meet her eye. When I did her look was a puzzle of anger held back, of curiosity, of hurt. She was trying to understand what had happened to her daughter.

I had grown used to the smell of linseed oil. I even kept a small bottle of it by my bed. In the mornings when I was getting dressed I held it up to the window to admire the colour, which was like lemon juice with a drop of lead-tin yellow in it.

I wear that colour now, I wanted to say. He is painting me in that colour.

Instead, to take my father's mind off the smell, I described the other painting my master was working on. ‘A young woman sits at a harpsichord, playing. She is wearing a yellow and black bodice — the same the baker's daughter wore for her painting — a white satin skirt and white ribbons in her hair. Standing in the curve of the harpsichord is another woman, who is holding music and singing. She wears a green, fur-trimmed housecoat and a blue dress. In between the women is a man sitting with his back to us-’

‘Van Ruijven,’ my father interrupted.

‘Yes, van Ruijven. All that can be seen of him is his back, his hair, and one hand on the neck of a lute.’

‘He plays the lute badly,’ my father added eagerly.

‘Very badly. That's why his back is to us — so we won't see that he can't even hold his lute properly.’

My father chuckled, his good mood restored. He was always pleased to hear that a rich man could be a poor musician.

It was not always so easy to bring him back into good humour. Sundays had become so uncomfortable with my parents that I began to welcome those times when Pieter the son ate with us. He must have noted the troubled looks my mother gave me, my father's querulous comments, the awkward silences so unexpected between parent and child. He never said anything about them, never winced or stared or became tongue-tied himself. Instead he gently teased my father, flattered my mother, smiled at me.

Pieter did not ask why I smelled of linseed oil. He did not seem to worry about what I might be hiding. He had decided to trust me.

He was a good man.

I could not help it, though — I always looked to see if there was blood under his fingernails.

He should soak them in salted water, I thought. One day I will tell him so.

He was a good man, but he was becoming impatient. He did not say so, but sometimes on Sundays in the alley off the Rietveld Canal, I could feel the impatience in his hands. He would grip my thighs harder than he needed, press his palm into my back so that I was glued to his groin and would know its bulge, even under many layers of cloth. It was so cold that we did not touch each other's skin — only the bumps and textures of wool, the rough outlines of our limbs.

Pieter's touch did not always repel me. Sometimes, if I looked over his shoulder at the sky, and found the colours besides white in a cloud, or thought of grinding lead white or massicot, my breasts and belly tingled, and I pressed against him. He was always pleased when I responded. He did not notice that I avoided looking at his face and hands.

That Sunday of the linseed oil, when my father and mother looked so puzzled and unhappy, Pieter led me to the alley later. There he began squeezing my breasts and pulling at their nipples through the cloth of my dress. Then he stopped suddenly, gave me a sly look, and ran his hands over my shoulders and up my neck. Before I could stop him his hands were up under my cap and tangled in my hair.

I held my cap down with both hands. ‘No!’

Pieter smiled at me, his eyes glazed as if he had looked too long at the sun. He had managed to pull loose a strand of my hair, and tugged it now with his fingers. ‘Some day soon, Griet, I will see all of this. You will not always be a secret to me.’ He let a hand drop to the lower curve of my belly and pushed against me. ‘You will be eighteen next month. I'll speak to your father then.’

I stepped back from him — I felt as if I were in a hot, dark room and could not breathe. ‘I am still so young. Too young for that.’

Pieter shrugged. ‘Not everyone waits until they're older. And your family needs me.’ It was the first time he had referred to my parents' poverty, and their dependence on him — their dependence which became my dependence as well. Because of it they were content to take the gifts of meat and have me stand in an alley with him on a Sunday.

I frowned. I did not like being reminded of his power over us.

Pieter sensed that he should not have said anything. To make amends he tucked the strand of hair back under my cap, then touched my cheek. ‘I'll make you happy, Griet,’ he said. ‘I will.’

After he left I walked along the canal, despite the cold. The ice had been broken so that boats could get through, but a thin layer had formed again on the surface. When we were children Frans and Agnes and I would throw stones to shatter the thin ice until every sliver had disappeared under water. It seemed a long time ago.

A month before he had asked me to come up to the studio.

‘I will be in the attic,’ I announced to the room that afternoon.

Tanneke did not look up from her sewing. ‘Put some more wood on the fire before you go,’ she ordered.

The girls were working on their lace, overseen by Maertge and Maria Thins. Lisbeth had patience and nimble fingers, and produced good work, but Aleydis was still too young to manage the delicate weaving, and Cornelia too impatient. The cat sat at Cornelia's feet by the fire, and occasionally the girl reached down and dangled a bit of thread for the creature to paw at. Eventually, she probably hoped, the cat would tear its claws through her work and ruin it.

After feeding the fire I stepped around Johannes, who was playing with a top on the cold kitchen tiles. As I left he spun it wildly, and it hopped straight into the fire. He began to cry while Cornelia shrieked with laughter and Maertge tried to haul the toy from the flames with a pair of tongs.

‘Hush, you'll wake Catharina and Franciscus,’ Maria Thins warned the children. They did not hear her.

I crept out, relieved to escape the noise, no matter how cold it would be in the studio.

The studio door was shut. As I approached it I pressed my lips together, smoothed my eyebrows, and ran my fingers down the sides of my cheeks to my chin, as if I were testing an apple to see if it was firm. I hesitated in front of the heavy wooden door, then knocked softly. There was no answer, though I knew he must be there — he was expecting me.

It was the first day of the new year. He had painted the ground layer of my painting almost a month before, but nothing since — no reddish marks to indicate the shapes, no false colours, no overlaid colours, no highlights. The canvas was a blank yellowish white. I saw it every morning as I cleaned.

I knocked louder.

When the door opened he was frowning, his eyes not catching mine. ‘Don't knock, Griet, just come in quietly,’ he said, turning away and going back to the easel, where the blank canvas sat waiting for its colours.

I closed the door softly behind me, blotting out the noise of the children downstairs, and stepped to the middle of the room. Now that the moment had come at last I was surprisingly calm. ‘You wanted me, sir.’

‘Yes. Stand over there.’ He gestured to the corner where he had painted the other women. The table he was using for the concert painting was set there, but he had cleared away the musical instruments. He handed me a letter. ‘Read that,’ he said.

I unfolded the sheet of paper and bowed my head over it, worried that he would discover I was only pretending to read an unfamiliar hand.

Nothing was written on the paper.

I looked up to tell him so, but stopped. With him it was often better to say nothing. I bowed my head again over the letter.

‘Try this instead,’ he suggested, handing me a book. It was bound in worn leather and the spine was broken in several places. I opened it at random and studied a page. I did not recognise any of the words.

He had me sit with the book, then stand holding it while looking at him. He took away the book, handed me the white jug with the pewter top and had me pretend to pour a glass of wine. He asked me to stand and simply look out the window. All the while he seemed perplexed, as if someone had told him a story and he couldn't recall the ending.

‘It is the clothes,’ he murmured. ‘That is the problem.’

I understood. He was having me do things a lady would do, but I was wearing a maid's clothes. I thought of the yellow mantle and the yellow and black bodice, and wondered which he would ask me to wear. Instead of being excited by the idea, though, I felt uneasy. It was not just that it would be impossible to hide from Catharina that I was wearing her clothes. I did not feel right holding books and letters, pouring myself wine, doing things I never did. As much as I wanted to feel the soft fur of the mantle around my neck, it was not what I normally wore.

‘Sir,’ I spoke finally, ‘perhaps you should have me do other things. Things that a maid does.’

‘What does a maid do?’ he asked softly, folding his arms and raising his eyebrows.

I had to wait a moment before I could answer — my jaw was trembling. I thought of Pieter and me in the alley and swallowed. ‘Sewing,’ I replied. ‘Mopping and sweeping. Carrying water. Washing sheets. Cutting bread. Polishing windowpanes.’

‘You would like me to paint you with your mop?’

‘It's not for me to say, sir. It is not my painting.’

He frowned. ‘No, it is not yours.’ He sounded as if he were speaking to himself.

‘I do not want you to paint me with my mop.’ I said it without knowing that I would.

‘No. No, you're right, Griet. I would not paint you with a mop in your hand.’

‘But I cannot wear your wife's clothes.’

There was a long silence. ‘No, I expect not,’ he said. ‘But I will not paint you as a maid.’

‘What, then, sir?’

‘I will paint you as I first saw you, Griet. Just you.’

He set a chair near his easel, facing the middle window, and I sat down. I knew it was to be my place. He was going to find the pose he had put me in a month before, when he had decided to paint me.

‘Look out the window,’ he said.

I looked out at the grey winter day and, remembering when I stood in for the baker's daughter, tried not to see anything but to let my thoughts become quiet. It was hard because I was thinking of him, and of me sitting in front of him.

The New Church bell struck twice.

‘Now turn your head very slowly towards me. No, not your shoulders. Keep your body turned towards the window. Move only your head. Slow, slow. Stop. A little more, so that — stop. Now sit still.’

I sat still.

At first I could not meet his eyes. When I did it was like sitting close to a fire that suddenly blazes up. Instead I studied his firm chin, his thin lips.

‘Griet, you are not looking at me.’

I forced my gaze up to his eyes. Again I felt as if I were burning, but I endured it — he wanted me to.

Soon it became easier to keep my eyes on his. He looked at me as if he were not seeing me, but someone else, or something else — as if he were looking at a painting.

He is looking at the light that falls on my face, I thought, not at my face itself. That is the difference.

It was almost as if I were not there. Once I felt this I was able to relax a little. As he was not seeing me, I did not see him. My mind began to wander — over the jugged hare we had eaten for dinner, the lace collar Lisbeth had given me, a story Pieter the son had told me the day before. After that I thought of nothing. Twice he got up to change the position of one of the shutters. He went to his cupboard several times to choose different brushes and colours. I viewed his movements as if I were standing in the street, looking in through the window.

The church bell struck three times. I blinked. I had not felt so much time pass. It was as if I had fallen under a spell.

I looked at him — his eyes were with me now. He was looking at me. As we gazed at each other a ripple of heat passed through my body. I kept my eyes on his, though, until at last he looked away and cleared his throat.

‘That will be all, Griet. There is some bone for you to grind upstairs.’

I nodded and slipped from the room, my heart pounding. He was painting me.

‘Pull your cap back from your face,’ he said one day.

‘Back from my face, sir?’ I repeated dumbly, and regretted it. He preferred me not to speak, but to do as he said. If I did speak, I should say something worth the words.

He did not answer. I pulled the side of my cap that was closest to him back from my cheek. The starched tip grazed my neck.

‘More,’ he said. ‘I want to see the line of your cheek.’

I hesitated, then pulled it back further. His eyes moved down my cheek.

‘Show me your ear.’

I did not want to. I had no choice.

I felt under the cap to make sure no hair was loose, tucking a few strands behind my ear. Then I pulled it back to reveal the lower part of my ear.

The look on his face was like a sigh, though he did not make a sound. I caught a noise in my own throat and pushed it down so that it would not escape.

‘Your cap,’ he said. ‘Take it off.’

‘No, sir.’

‘No?’

‘Please do not ask me to, sir.’ I let the cloth of the cap drop so that my ear and cheek were covered again. I looked at the floor, the grey and white tiles extending away from me, clean and straight.

‘You do not want to bare your head?’

‘No.’

‘Yet you do not want to be painted as a maid, with your mop and your cap, nor as a lady, with satin and fur and dressed hair.’

I did not answer. I could not show him my hair. I was not the sort of girl who left her head bare.

He shifted in his chair, then got up. I heard him go into the storeroom. When he returned, his arms were full of cloth, which he dropped in my lap.

‘Well, Griet, see what you can do with this. Find something here to wrap your head in, so that you are neither a lady nor a maid.’ I could not tell if he was angry or amused. He left the room, shutting the door behind him.

I sorted through the cloth. There were three caps, all too fine for me, and too small to cover my head fully. There were pieces of cloth, left over from dresses and jackets Catharina had made, in yellows and browns, blues and greys.

I did not know what to do. I looked around as if I would find an answer in the studio. My eyes fell on the painting of The Procuress — the young woman's head was bare, her hair held back with ribbons, but the old woman wore a piece of cloth wrapped around her head, crisscrossing in and out of itself. Perhaps that is what he wants, I thought. Perhaps that is what women who are neither ladies nor maids nor the other do with their hair.

I chose a piece of brown cloth and took it into the storeroom, where there was a mirror. I removed my cap and wound the cloth around my head as best I could, checking the painting to try to imitate the old woman's. I looked very peculiar.

I should let him paint me with a mop, I thought. Pride has made me vain.

When he returned and saw what I had done, he laughed. I had not heard him laugh often — sometimes with the children, once with van Leeuwenhoek. I frowned. I did not like being laughed at.

‘I have only done what you asked, sir,’ I muttered.

He stopped chuckling. ‘You're right, Griet. I'm sorry. And your face, now that I can see more of it, it is —’ He stopped, never finishing his sentence. I always wondered what he would have said.

He turned to the pile of cloth I had left on my chair. ‘Why did you choose brown,’ he asked, ‘when there are other colours?’

I did not want to speak of maids and ladies again. I did not want to remind him that blues and yellows were ladies' colours. ‘Brown is the colour I usually wear,’ I said simply.

He seemed to guess what I was thinking. ‘Tanneke wore blue and yellow when I painted her some years ago,’ he countered.

‘I am not Tanneke, sir.’

‘No, that you certainly are not.’ He pulled out a long, narrow band of blue cloth. ‘None the less, I want you to try this.’

I studied it. ‘That is not enough cloth to cover my head.’

‘Use this as well, then.’ He picked up a piece of yellow cloth that had a border of the same blue and held it out to me.

Reluctantly I took the two pieces of cloth back to the storeroom and tried again in front of the mirror. I tied the blue cloth over my forehead, with the yellow piece wound round and round, covering the crown of my head. I tucked the end into a fold at the side of my head, adjusted folds here and there, smoothed the blue cloth round my head, and stepped back into the studio.

He was looking at a book and did not notice as I slipped into my chair. I arranged myself as I had been sitting before. As I turned my head to look over my left shoulder, he glanced up. At the same time the end of the yellow cloth came loose and fell over my shoulder.

‘Oh,’ I breathed, afraid that the cloth would fall from my head and reveal all my hair. But it held — only the end of the yellow cloth dangled free. My hair remained hidden.

‘Yes,’ he said then. ‘That is it, Griet. Yes.’

He would not let me see the painting. He set it on a second easel, angled away from the door, and told me not to look at it. I promised not to, but some nights I lay in bed and thought about wrapping my blanket around me and stealing downstairs to see it. He would never know.

But he would guess. I did not think I could sit with him looking at me day after day without guessing that I had looked at the painting. I could not hide things from him. I did not want to.

I was reluctant, too, to discover how it was that he saw me. It was better to leave that a mystery.

The colours he asked me to mix gave no clues as to what he was doing. Black, ochre, lead white, lead-tin yellow, ultramarine, red lake — they were all colours I had worked with before, and they could as easily have been used for the concert painting.

It was unusual for him to work on two paintings at once. Although he did not like switching back and forth between the two, it did make it easier to hide from others that he was painting me. A few people knew. Van Ruijven knew — I was sure it was at his request that my master was making the painting. My master must have agreed to paint me alone so that he would not have to paint me with van Ruijven. Van Ruijven would own the painting of me.

I was not pleased by this thought. Nor, I believed, was my master.

Maria Thins knew about the painting as well. It was she who probably made the arrangement with van Ruijven. And besides, she could still go in and out of the studio as she liked, and could look at the painting, as I was not allowed to. Sometimes she looked at me sideways with a curious expression she could not hide.

I suspected Cornelia knew about the painting. I caught her one day where she should not be, on the stairs leading to the studio. She would not say why she was there when I asked her, and I let her go rather than bring her to Maria Thins or Catharina. I did not dare stir things up, not while he was painting me.

Van Leeuwenhoek knew about the painting. One day he brought his camera obscura and set it up so they could look at me. He did not seem surprised to see me sitting in my chair — my master must have warned him. He did glance at my unusual head cloth, but did not comment.

They took turns using the camera. I had learned to sit without moving or thinking, and without being distracted by his gaze. It was harder, though, with the black box pointed at me. With no eyes, no face, no body turned towards me, only a box and a black robe covering a humped back, I became uneasy. I could no longer be sure of how they were looking at me.

I could not deny, however, that it was exciting to be studied so intently by two gentlemen, even if I could not see their faces.

My master left the room to find a soft cloth to polish the lens. Van Leeuwenhoek waited until his tread could be heard on the stairs, then said softly, ‘You watch out for yourself, my dear.’

‘What do you mean, sir?’

‘You must know that he's painting you to satisfy van Ruijven. Van Ruijven's interest in you has made your master protective of you.’

I nodded, secretly pleased to hear what I had suspected.

‘Do not get caught in their battle. You could be hurt.’

I was still holding the position I had assumed for the painting. Now my shoulders twitched of their own accord, as if I were shaking off a shawl. ‘I do not think he would ever hurt me, sir.’

‘Tell me, my dear, how much do you know of men?’

I blushed deeply and turned my head away. I was thinking of being in the alley with Pieter the son.

‘You see, competition makes men possessive. He is interested in you in part because van Ruijven is.’

I did not answer.

‘He is an exceptional man,’ van Leeuwenhoek continued. ‘His eyes are worth a room full of gold. But sometimes he sees the world only as he wants it to be, not as it is. He does not understand the consequences for others of his point of view. He thinks only of himself and his work, not of you. You must take care then—’ He stopped. My master's footsteps were on the stairs.

‘Take care to do what, sir?’ I whispered.

‘Take care to remain yourself.’

I lifted my chin to him. ‘To remain a maid, sir?’

‘That is not what I mean. The women in his paintings — he traps them in his world. You can get lost there.’

My master came into the room. ‘Griet, you have moved,’ he said.

‘I am sorry, sir.’ I took up my position once more.

Catharina was six months pregnant when he began the painting of me. She was large already, and moved slowly, leaning against walls, grabbing the backs of chairs, sinking heavily into one with a sigh. I was surprised by how hard she made carrying a child seem, given that she had done so several times already. Although she did not complain aloud, once she was big she made every movement seem like a punishment she was being forced to bear. I had not noticed this when she was carrying Franciscus, when I was new to the house and could barely see beyond the pile of laundry waiting for me each morning.

As she grew heavier Catharina became more and more absorbed in herself. She still looked after the children, with Maertge's help. She still concerned herself with the housekeeping, and gave Tanneke and me orders. She still shopped for the house with Maria Thins. But part of her was elsewhere, with the baby inside. Her harsh manner was rare now, and less deliberate. She slowed down, and though she was clumsy she broke fewer things.

I worried about her discovering the painting of me. Luckily the stairs to the studio were becoming awkward for her to climb, so that she was unlikely to fling open the studio door and discover me in my chair, him at his easel. And because it was winter she preferred to sit by the fire with the children and Tanneke and Maria Thins, or doze under a mound of blankets and furs.

The real danger was that she would find out from van Ruijven. Of the people who knew of the painting, he was the worst at keeping a secret. He came to the house regularly to sit for the concert painting. Maria Thins no longer sent me on errands or told me to make myself scarce when he came. It would have been impractical — there were only so many errands I could run. And she must have thought he would be satisfied with the promise of a painting, and would leave me alone.

He did not. Sometimes he sought me out, while I was washing or ironing clothes in the washing kitchen, or working with Tanneke in the cooking kitchen. It was not so bad when others were around — when Maertge was with me, or Tanneke, or even Aleydis, he simply called out, ‘Hello, my girl,’ in his honeyed voice and left me in peace. If I was alone, however, as I often was in the courtyard, hanging up laundry so it could catch a few minutes of pale winter sunlight, he would step into the enclosed space, and behind a sheet I had just hung, or one of my master's shirts, he would touch me. I pushed him away as politely as a maid can a gentleman. None the less he managed to become familiar with the shape of my breasts and thighs under my clothes. He said things to me that I tried to forget, words I would never repeat to anyone else.

Van Ruijven always visited Catharina for a few minutes after sitting in the studio, his daughter and sister waiting patiently for him to finish gossiping and flirting. Although Maria Thins had told him not to say anything to Catharina about the painting, he was not a man to keep secrets quietly. He was very pleased that he was to have the painting of me, and he sometimes dropped hints about it to Catharina.

One day as I was mopping the hallway I overheard him say to her, ‘Who would you have your husband paint, if he could paint anyone in the world?’

‘Oh, I don't think about such things,’ she laughed in reply. ‘He paints what he paints.’

‘I don't know about that.’ Van Ruijven worked so hard to sound sly that even Catharina could not miss the hint.

‘What do you mean?’ she demanded.

‘Nothing, nothing. But you should ask him for a painting. He might not say no. He could paint one of the children — Maertge, perhaps. Or your own lovely self.’

Catharina was silent. From the way van Ruijven quickly changed the subject he must have realised he had said something that upset her.

Another time when she asked if he enjoyed sitting for the painting he replied, ‘Not as much as I would if I had a pretty girl to sit with me. But soon enough I'll have her anyway, and that will have to do, for now.’

Catharina let this remark pass, as she would not have done a few months before. But then, perhaps it did not sound so suspicious to her since she knew nothing of the painting. I was horrified, though, and repeated his words to Maria Thins.

‘Have you been listening behind doors, girl?’ the old woman asked.

‘I—’ I could not deny it.

Maria Thins smiled sourly. ‘It's about time I caught you doing things maids are meant to do. Next you'll be stealing silver spoons.’

I flinched. It was a harsh thing to say, especially after all the trouble with Cornelia and the combs. I had no choice, though — I owed Maria Thins a great deal. She must be allowed her cruel words.

‘But you're right, van Ruijven's mouth is looser than a whore's purse,’ she continued. ‘I will speak to him again.’

Saying something to him, however, was of little use — it seemed to spur him on even more to make suggestions to Catharina. Maria Thins took to being in the room with her daughter when he visited so that she could try to rein in his tongue.

I did not know what Catharina would do when she discovered the painting of me. And she would, one day — if not in the house, then at van Ruijven's, where she would be dining and look up and see me staring at her from a wall.

He did not work on the painting of me every day. He had the concert to paint as well, with or without van Ruijven and his women. He painted around them when they were not there, or asked me to take the place of one of the women — the girl sitting at the harpsichord, the woman standing next to it singing from a sheet of paper. I did not wear their clothes. He simply wanted a body there. Sometimes the two women came without van Ruijven, and that was when he worked best. Van Ruijven himself was a difficult model. I could hear him when I was working in the attic. He could not sit still, and wanted to talk and play his lute. My master was patient with him, as he would be with a child, but sometimes I could hear a tone creep into his voice and knew that he would go out that night to the tavern, returning with eyes like glittering spoons.

I sat for him for the other painting three or four times a week, for an hour or two each time. It was the part of the week I liked best, with his eyes on only me for those hours. I did not mind that it was not an easy pose to hold, that looking sideways for long periods of time gave me headaches. I did not mind when sometimes he had me move my head again and again so that the yellow cloth swung around, so that he could paint me looking as if I had just turned to face him. I did whatever he asked of me.

He was not happy, though. February passed and March arrived, with its days of ice and sun, and he was not happy. He had been working on the painting for almost two months, and though I had not seen it, I thought it must be close to done. He was no longer having me mix quantities of colour for it, but used tiny amounts and made few movements with his brushes as I sat. I had thought I understood how he wanted me to be, but now I was not sure. Sometimes he simply sat and looked at me as if he were waiting for me to do something. Then he was not like a painter, but like a man, and it was hard to look at him.

One day he announced suddenly, as I was sitting in my chair, ‘This will satisfy van Ruijven, but not me.’

I did not know what to say. I could not help him if I had not seen the painting. ‘May I look at the painting, sir?’

He gazed at me curiously.

‘Perhaps I can help,’ I added, then wished I had not. I was afraid I had become too bold.

‘All right,’ he said after a moment.

I got up and stood behind him. He did not turn round, but sat very still. I could hear him breathing slowly and steadily.

The painting was like none of his others. It was just of me, of my head and shoulders, with no tables or curtains, no windows or powderbrushes to soften and distract. He had painted me with my eyes wide, the light falling across my face but the left side of me in shadow. I was wearing blue and yellow and brown. The cloth wound round my head made me look not like myself, but like Griet from another town, even from another country altogether. The background was black, making me appear very much alone, although I was clearly looking at someone. I seemed to be waiting for something I did not think would ever happen.

He was right — the painting might satisfy van Ruijven, but something was missing from it.

I knew before he did. When I saw what was needed — that point of brightness he had used to catch the eye in other paintings — I shivered. This will be the end, I thought.

I was right.

This time I did not try to help him as I had with the painting of van Ruijven's wife writing a letter. I did not creep into the studio and change things — reposition the chair I sat in or open the shutters wider. I did not wrap the blue and yellow cloth differently or hide the top of my chemise. I did not bite my lips to make them redder, or suck in my cheeks. I did not set out colours I thought he might use.

I simply sat for him, and ground and washed the colours he asked for.

He would find it for himself anyway.

It took longer than I had expected. I sat for him twice more before he discovered what was missing. Each time I sat he painted with a dissatisfied look on his face, and dismissed me early.

I waited.

Catharina herself gave him the answer. One afternoon Maertge and I were polishing shoes in the washing kitchen while the other girls had gathered in the great hall to watch their mother dress for a birth feast. I heard Aleydis and Lisbeth squeal, and knew Catharina had brought out her pearls, which the girls loved.

Then I heard his tread in the hallway, silence, then low voices. After a moment he called out, ‘Griet, bring my wife a glass of wine.’

I set the white jug and two glasses on a tray, in case he chose to join her, and took them to the great hall. As I entered I bumped against Cornelia, who had been standing in the doorway. I managed to catch the jug, and the glasses clattered against my chest without breaking. Cornelia smirked and stepped out of my way.

Catharina was sitting at the table with her powderbrush and jar, her combs and jewellery box. She was wearing her pearls and her green silk dress, altered to cover her belly. I placed a glass near her and poured.

‘Would you like some wine too, sir?’ I asked, glancing up. He was leaning against the cupboard that surrounded the bed, pressed against the silk curtains, which I noticed for the first time were made of the same cloth as Catharina's dress. He looked back and forth between Catharina and me. On his face was his painter's look.

‘Silly girl, you've spilled wine on me!’ Catharina pushed away from the table and brushed at her belly with her hand. A few drops of red had splashed there.

‘I'm sorry, madam. I'll get a damp cloth to sponge it.’

‘Oh, never mind. I can't bear to have you fussing about me. Just go.’

I stole a look at him as I picked up the tray. His eyes were fixed on his wife's pearl earring. As she turned her head to brush more powder on her face the earring swung back and forth, caught in the light from the front windows. It made us all look at her face, and reflected light as her eyes did.

‘I must go upstairs for a moment,’ he said to Catharina. ‘I won't be long.’

That is it, then, I thought. He has his answer.

When he asked me to come to the studio the next afternoon, I did not feel excited as I usually did when I knew I was to sit for him. For the first time I dreaded it. That morning the clothes I washed felt particularly heavy and sodden, and my hands not strong enough to wring them well. I moved slowly between the kitchen and the courtyard, and sat down to rest more than once. Maria Thins caught me sitting when she came in for a copper pancake pan. ‘What's the matter, girl? Are you ill?’ she asked.