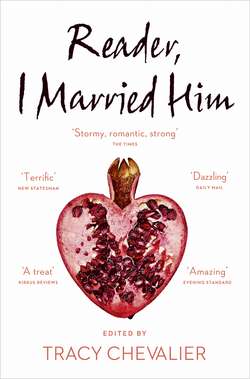

Читать книгу Reader, I Married Him - Tracy Chevalier - Страница 10

SARAH HALL

ОглавлениеIT WAS THE LAST week of the season and the lido was nearly deserted. She arrived at the usual time, changed into her suit, left her clothes in a locker and walked out across the chlorine-scented vault. The concrete paving had traces of frost in the corners and was almost painful on the soles of her feet. Light rustled under the blue rectangular surface. She climbed down the metal ladder and moved away from the edge without pausing. In October, entering the unheated pool was an act of bravery; the trick was to remain thoughtless. The water was coldly radiant. Her limbs felt stiff as she kicked and her chin burned. At the halfway mark she looked up at the guard, who was sinking into the fur hood of his parka. Nothing in his demeanour gave the impression of a man ready to intervene, should it be necessary. She took a breath, put her head underwater, surfacing a few strokes later. She was awake now, her heart jabbing. She turned on to her back, rotated her arms. The clouds above were grey and fast. Rain later, perhaps.

She swam twenty lengths, by which time she was warm and the idea of autumn seemed acceptable, then rested her head on the coping and caught her breath. The pool slopped gently against her chest. Light filaments flashed and extinguished in the rocking fluid. In summer it was hard to swim, hard to find the space; the pool was choppy, kids bombed in at the deep end, and the water washed out over the edges, soaking towels and bags. Barely an inch between sunbathers. Not many came after early September. But the old couple with rubber caps she always saw on quieter mornings were in the next lane, swimming side by side: her chin tipped high, his submerged. She followed in their wake. They nodded hello when she reached the end, and she smiled. She climbed out. Her breasts and thighs were blotched red with the chill and exertion.

In the changing room she tried not to look at her midriff in the mirrors, the crêping and the sag. She showered and dressed, and went into the poolside café. It was busy as usual. There were prams parked between tables, people working on laptops and reading books. The debris of muesli, pastries and napkins was strewn about. On the walls were photographs from the thirties, pictures of young women diving from the high board, now dismantled, or posing with their hands on their hips. The grace, the vivacity of another era: dark mouths, straight teeth, a kind of ebullient confidence. The scenes looked pre-industrial – open sky, birds in vee formations overhead. The five-storey civic building opposite the park hadn’t been built. London had not yet arrived.

The man behind the counter leaned away from the growling espresso machine and predicted her order.

Latte?

Yes, please.

There was an immaculate row of silver rings in his bottom lip.

Bring it over.

She took a seat by the window, in the corner, and watched the old couple emerge from the lido. Their stamina was far greater than hers – an hour’s swimming at least. They stood dripping and chatting for a moment as if unaffected by the smart breeze. The woman’s legs were thin, but strung with muscle. Her belly was a tiny mound under the swimming costume. The man had a buckled torso, a white beard. There was a vast laparotomy scar up his abdomen. They were the same height and seemed perfectly suited. She wondered if they’d evolved towards their symmetry over the years. The couple parted and went towards separate changing rooms. He walked awkwardly, favouring one hip. In the pool he swam well. Occasionally she’d seen his sedate, companionable breaststroke morph into an energetic butterfly.

There was no one left in the lido. The guard rested his head on his hand, eyes closed, the whistle attached to his wrist hanging in the air. The surface of the pool stilled to a beautiful chemical blue.

Her coffee arrived. She opened a packet of sugar and poured it. She shouldn’t be taking sugar – the baby weight was still not coming off – but hadn’t ever been able to drink coffee without. She sipped slowly. The pool was hypnotic; something about the water was calming, rapturous almost. Time here, after swimming, always felt inadmissible to her day. She would linger, ignore her phone. Often she had to race round the shops to be back in time for the sitter. “Luxury hour”, Daniel called it, as if she were indulging herself, but it was the only time she had without the baby.

After a while she went to the counter, paid and left. She began to walk through the park. The breeze was strengthening, the leaves of the trees moving briskly. There were some kids playing cycle polo on one of the hard courts, wheeling about and whacking the puck against the metal cage. Dogs bounded across the grass. She passed the glass merchant’s mansion and the old glassworks, both hidden under flapping plastic drapes and renovation scaffolding. She’d hated the city when she and Daniel had first arrived. She’d missed the Devon countryside, the fragrance of peat and gorse, horses with torn manes, the lack of people. But it was what one did – for the jobs, for the culture; London’s sacrificial gravity was too strong and it had taken them. Discovering the park had changed everything, and the nearby property was just about affordable.

She passed through the rank of dark-trunked sycamores. Beyond was the meadow. Its pale brindle stirred in the wind, belts of grass lightening and darkening. The field had been resown after a local campaign by the Friends of the Park. For a century it had been a wasteland – the horses used for pulling the carts of quartz sand to the glassworks had overgrazed it. Dust, cullet and oil from the annealing ovens had polluted the soil. Now it was lush again; there were bees and mice, even city kestrels – she’d seen them tremoring above the burrows, stooping with astonishing speed. There was a dry, chaff-like smell to the meadow after the summer; the grasses clicked and hushed. The enormous, elaborate spider webs of the previous month had broken apart and were drifting free.

A man was walking down the scythed path towards her. She stepped aside to let him pass but he stopped and held out his hand.

Alex.

She looked up. For a second she didn’t recognise him. He had on a tie and a suit jacket. The planes of his face came into focus. The heavy bones, the irises, with their concentration of colour, no divisions or rings. He was a little older, his hair darker than she remembered, but it was him.

Oh, God, she said. Hi.

He moved to kiss her cheek. She put a hand on his arm, turned her face too much and he kissed her ear, awkwardly.

Hi. Do you still live around here?

Yes, I’m over on Hillworth. Near the station.

Nice area.

Yes.

The wind was throwing her hair around her face, tangling it. She hadn’t properly washed or brushed it in the changing room. She moved a damp strand from her forehead. It felt sticky with chlorine. He was looking at her, his expression unreadable.

I’ve been swimming.

At the lido?

She nodded.

Wow! It’s still open? I must go there. Is it cold?

It’s OK. Bracing.

Had he forgotten? The cold water never used to bother him. She ran a hand through her hair again, tried to think what to say. Her mind felt white, soft. The shock of the real. Even though he’d said he was going, she’d expected to run into him and had, for a time, avoided the park. After a few months the expectation had lessened, and the hope, and she had reclaimed the space. Then the baby had come, and life had altered drastically. She’d assumed he’d moved away for good. His face was becoming increasingly familiar as she looked. The shape of his mouth, too full, voluptuous for a man, the fine white scar in the upper lip.

So, where are you these days? she asked.

Brighton.

Brighton!

I know!

He smiled. His teeth. One of the front ones was a fraction squarer, mostly porcelain – the accident on his bike. She had liked tapping it, then the tooth next to it, to hear the difference. Heat bloomed up her neck. These days she could not remember things – where her purse was, which breast she had last fed the baby on, the name of the artist from her university dissertation. But she could remember his mouth, and lying so close to his face that the details began to blur. She felt as if she might reach out now and touch the hard wet surface of his tooth. She put her hands in her coat pockets. Around them the grass was swaying and hissing. The silk webs floated. A bird darted up out of the field, flew a few feet and then disappeared between stalks.

He was studying her too. Probably she looked tired, leached, aged, the classic new mother, not like the woman who had come up to him in a low-cut swimsuit and asked to borrow change for the locker.

I’ll pay you back tomorrow.

I might not be here tomorrow.

Yes, you will.

So confident, then.

She hadn’t applied make-up, there was no point most days really, and her mouth was dry and bitter from the coffee. At least the long coat hid her figure.

Did you go to Burma? she asked.

Myanmar, he said, quietly. I did. For eighteen months. Well, officially to Thailand for eighteen months, but we went across the border most days into the training camps.

I thought you would.

Now it’s not such a problem getting in. Tourism.

She nodded. She was not up to speed on such things any more; she’d lost interest.

Was it difficult?

She was not sure what she meant by this question, only that she imagined privation, forfeit, that he had made the wrong decision.

Sometimes. We had a decent team. A lot of them were more missionaries than medics really, but on the whole the quality was good. I don’t know whether we helped really. The students qualify, then get arrested for practising.

He shrugged. He glanced towards the north end of the park.

So it’s still open?

Yes. Last week before winter closing. You should go before it shuts.

For old times’ sake. She did not say it. Nor, why have you come back?

He glanced at his watch.

I have a conference. I’m presenting the first paper, actually. I have to get to Barts.

Oh, great. Congratulations.

Hence the suit, the tidy version of his former self. He shrugged again. Humility; the duty was clearly very important. There was a pause. She could barely look at him; the past was restoring itself too viscerally. Since the baby she had felt nothing, no desire, not even sorrow that this part of her life had vanished, perhaps for good. Daniel had been understanding, patient. She couldn’t explain it: breastfeeding, different priorities, the wrong smell. Now, that familiar low ache. She wanted to step forward, reach out. Compatible immune systems, he had once said, to explain their impulses, that’s what it really is. For something to do she took her bag off her shoulder and rummaged around inside. It was a pointless act, spurred by panic; she was looking for nothing in particular. But then, in the inside pocket, she found the season ticket. She held it out.

Here. It still has a couple of swims. They won’t check the name when they stamp it, they never do.

He took the pass.

You should go, since you’re here.

That’s so thoughtful of you. God, I do miss it!

He was grinning now, and she could see in him the uninhibited man who’d never cared about the cold, who’d plunged into the pool without hesitation and swum almost a length under the surface. She could see his damp body on the bed in his flat, those stolen moments, the chaos of sheets, his expression, agonised, abandoned, as if in a seizure dream. She could see herself, holding the railings of the bed, fighting for control of the space they were using. Walking quickly home, ashamed, electrified, and holding her swimsuit under the kitchen tap, so that it would look used. Luxury hour.

She still swam, in October. Perhaps he was impressed because his interest suddenly seemed piqued.

So, Alexandra. What’s your life like now? Are you still at the gallery?

No. I’m married.

Ah.

She looked at him, then away.

To Daniel?

Yes, to Daniel.

Any children?

There was nothing to his tone other than polite conversation, the logical assumption of one thing following another. Or perhaps a slight wistfulness, some emotion, it was always hard to tell. The wind moved across the meadow. The grass rippled, like dry water.

No. No children.

He nodded, neither surprised nor sympathetic. She looked at the meadow. As if it could be as it was before. It was suddenly harder to breathe, though there were acres of air above. The lie was so great there would surely be a penalty. She would go home and the house would be silent, her son’s room empty. Or the baby would be screaming in the cot, and he would turn to ash when she lifted him up. The baby would be motionless in the shallow water of the bath while the minder sat on a stool, waiting.

He was speaking, saying something about his engagement to a woman from Thailand; her name was Sook, his family liked her, they had no children yet either. He was holding the season pass. He looked contented, established, a man in a tie about to give an important paper. Everything had moved on, except that he was here, and this was not the way to Barts. She reached out and touched his arm. He was real, of course he was.

You should swim, she said. Will you swim?

He looked at his watch again.

Yeah. Why not. I reckon there’s time, if I’m quick. What shall I wear? Will I get away with boxers?

I have to go, she said.

Oh. OK.

It was too abrupt, she knew, a breach in the otherwise civil conversation between old lovers that should have wound up more carefully. But already she had turned and was walking away up the path. His voice, calling behind her:

Bye, Alex. Lovely seeing you.

She kept walking. She did not turn round. At the edge of the meadow she stepped off the track, put her bag down, and crouched in the grass. He would not follow her, she knew, but she stayed there a long time, hidden. From her bag came the faint sound of ringing. She was late for the sitter again. She stayed crouched until her legs felt stiff. Embedded in the earth, between stalks, were tiny pieces of brown glass from the old works. The wind had lessened, the rain still holding off. She stood. If she ran back to the lido maybe she could catch him. She could apologise, and explain, tell him that she’d been afraid, she’d been angry and hurt that he was leaving; she’d had to choose, as he’d had to choose. The baby was a complication, but she could tell him what the child’s name was, at least. They could exchange numbers. They could meet, somewhere between Brighton and here. Or she could just watch him swimming from the café window, from the corner table, behind the blind pane, his body a long shadow under the surface.