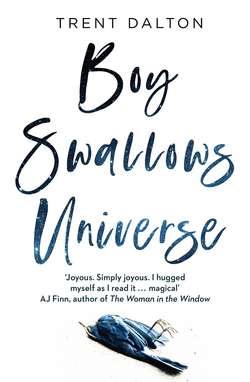

Читать книгу Boy Swallows Universe - Trent Dalton - Страница 11

ОглавлениеBoy Kills Bull

Here’s Mum through a half-open bedroom door. She stands in her red going-out dress in front of the mirror hanging on the inside door of her wardrobe, fixing a silver necklace around her neck. How could any sane man not be happy in her presence, not be content, not be grateful for what he’s got to come home to?

Why would my father fuck that up? She’s so fucking wondrous my mum that it fills me with rage. Fuck any and all of those fuckers who stood within a foot of her without first seeking permission from Zeus.

I pad into her bedroom, sit on the bed near her at the mirror.

‘Mum?’

‘Yes, matey.’

‘Why did you run from my father?’

‘Eli, I don’t want to talk about this now.’

‘He did bad things to you, didn’t he?’

‘Eli, that’s a conversation—’

‘We’ll have when I’m older,’ I say. The go-to line.

She gives a half-smile into the wardrobe mirror. Half apologetic. Half touched I give a shit.

‘Your father wasn’t well,’ she says.

‘Is my father a good man?’

Mum thinks. Mum nods.

‘Is my father more like me or more like Gus?’

Mum thinks. Mum says nothing.

‘Does Gus ever scare you?’

‘No.’

‘Sometimes he scares the shit out of me.’

‘Watch your language.’

Watch my language? Watch my language? This is what really shits me, when the clandestine heroin operation truth meets the Von Trapp family values mirage we’ve built for ourselves.

‘Sorry,’ I say.

‘What scares you?’ Mum asks.

‘I don’t know, the stuff he says, the stuff he writes in the air with his magic finger wand. Sometimes it doesn’t make sense and sometimes it makes sense only two years later or a month later when it’s impossible for him to have known it would make sense.’

‘Like what?’

‘Caitlyn Spies.’

‘Caitlyn Spies? Who’s Caitlyn Spies?’

‘That’s just the thing. We have no idea whatsoever, but ages ago Slim and I were messing around in the LandCruiser and we were watching August write his little messages in thin air and we caught him writing that name over and over. Caitlyn Spies. Caitlyn Spies. Caitlyn Spies. Then, last week, we read this big article in the South-West Star, this big “Queensland Remembers” spread, and it’s all about Slim, it’s the whole story of the Houdini of Boggo Road and it’s a really interesting piece and then we see the name of the woman who wrote it squeezed down in the bottom right-hand corner of the page.’

‘Caitlyn Spies,’ Mum says.

‘How’d you know?’

‘You were kinda setting it up for that, buddy.’

She moves to her jewellery box on a white chest of drawers. ‘He’s obviously been reading her pieces in the local rag. He probably just liked how her name sounded in his mind. He does that, latches on to a name or a word and runs it over and over again in his mind. Just because he doesn’t speak words doesn’t mean he doesn’t love them.’

She clutches two green gem earrings in her hand and leans down to me, talking softly and carefully.

‘That boy loves you more than he loves anything in this universe,’ she says. ‘When you were born . . .’

‘Yeah, I know, I know.’

‘. . . he watched over you so carefully, guarded your crib like all of human life depended on it. I couldn’t drag him away from you. He’s the best friend you will ever have.’

She stands and turns to the mirror.

‘How do I look?’

‘You look beautiful, Mum.’

Keeper of lightning. Goddess of fire and war and wisdom and Winfield Reds.

‘Mutton dressed up as lamb,’ she says.

‘What does that mean?’

‘I’m an old mutton dressing up as a young lamb.’

‘Don’t say that,’ I say, frustrated.

She sees my mood in the mirror.

‘Hey, I’m just joking,’ she says, fixing her earrings in.

I hate it when she puts herself down, self-worth being, I believe, a fairly major root cause of everything from our living in this street to my outfit tonight, a yellow polo shirt and a pair of black slacks all purchased from the St Vincent de Paul Society opportunity shop in the neighbouring suburb of Oxley.

‘You’re too good for this place, you know,’ I say.

‘What are you talking about?’

‘You’re too good for this house. You’re too smart for this town. You’re too good for Lyle. What are we doing here in this shithole? We shouldn’t even fucking be here.’

‘All right, thanks for the heads-up, matey. I think you can go finish getting ready now, huh?’

‘All those arseholes got the lamb because she always thought she was mutton.’

‘That’s enough now, Eli.’

‘You know you should have been a lawyer. You should have been a doctor. Not a fucking drug dealer.’

Her hard slap hits my shoulder before she’s even turned around.

‘Get out of my room,’ she barks. Another slap on my shoulder with her right hand, then another with her left on the other shoulder.

‘Get the hell out of my room, Eli!’ she screams. Her teeth are gritted so tight I see the creases in her top lip, breathing hard, breathing deep.

‘Who are we kidding?’ I shout. ‘Watch my language? Watch my language? We’re fucking drug dealers. Drug dealers fucking swear. I’m sick of all these bullshit airs and graces you and Lyle go on with. Do your homework, Eli. Eat your fuckin’ broccoli, Eli. Tidy this kitchen, Eli. Study hard, Eli. Like we’re the fucking Brady Bunch or somethin’ and not just a dirty bunch of smack pushers. Give me a fucking bre—’

Then I’m flying. Two hands grip my underarms from behind and I’m flying, hurled off Mum and Lyle’s bed, shoulders first, head second, into their bedroom door. I bounce off the door and drop to the polished wooden floorboards in a bone heap. Lyle looms above me and kicks me in the arse so hard with his Dunlop Volleys – his going-out shoes, one step up from his rubber flip-flops – that I belly slide two metres across the hallway floor to the bare feet of August who gives a curious This again? So soon? look to Lyle.

‘Fuck you, druggo cunt,’ I scream, rabid and groggy, trying to get to my feet.

He kicks me in the arse again and I dive this time across the living room floor.

Mum’s screaming behind him. ‘Stop it, Lyle, that’s enough.’

Lyle’s got the red-mist rage I’ve had the misfortune of encountering thrice before. Once when I ran away from home and slept a night in an empty bus in a wrecker’s yard in Redlands. Another time when I stuck six cane toads in the freezer to die a humane death and those hardy and uneasy-on-the-eye amphibians survived in that sub-zero coffin all the way through to Lyle’s after-work rum and Coke and he opened the freezer to find two toads blinking on his ice tray. A third time when I joined a schoolmate, Jock Whitney, on a neighbourhood doorknock fundraising drive for the Salvation Army, except we were really fundraising to buy ET the Extra Terrestrial on Atari – I still feel rotten about that, the game was a piece of shit.

August, dear, pure-of-heart August, stands in front of Lyle as he approaches for a third arse punt. He shakes his head, holding Lyle’s shoulders.

‘It’s all right, mate,’ Lyle says. ‘It’s time Eli and I had a little talk.’

Lyle brushes past August and he hauls me up by the collar of my opportunity shop polo, then pushes me out the front door. He hauls me down the front stairs and along the path, through the gate, still holding my collar, his big streetfightin’ fists pushing against the back of my neck. ‘Keep walkin’, smartarse,’ he says. ‘Keep walkin’.’

He takes me across the street, under the streetlight outshining the moon above us, into the park opposite our house. All I can smell is Lyle’s Old Spice aftershave. All I can hear is our footsteps and the sound of cicadas rubbing their legs, like they’re excited by the tension in the air, rubbing their legs the way Lyle rubs his hands before an Eels preliminary final.

‘What the fuck’s got into you, Eli?’ he asks, forcing me on across the cricket oval grass, unmown so my shoes keep kicking up the black fur of the tall paspalum grass shoots onto my pant legs. He walks me to the centre of the cricket pitch and he lets me go. He paces back and forth, fixing the buckle on his belt, breathing in, breathing out. He’s wearing his cream-coloured slacks with his blue cotton button-up shirt with the white tall ship cutting full mast across it.

Don’t cry, Eli. Don’t cry. Don’t cry. Fuck. You pussy, Eli.

‘Why are you crying?’ Lyle asks.

‘I don’t know, I really didn’t want to. My brain doesn’t listen to me.’

I cry some more with this realisation. Lyle gives me a minute. I wipe my eyes.

‘You all right?’ Lyle asks.

‘Me arse stings a bit.’

‘Sorry about that.’

I shrug. ‘I deserved it,’ I say.

Lyle gives me another moment.

‘You ever wonder why you cry so easy, Eli?’

‘Because I’m a pussy.’

‘You’re not a pussy. Don’t you ever be ashamed of crying. You cry because you give a shit. Don’t ever be ashamed of giving a shit. Too many people in this world are too scared to cry because they’re too scared to give a shit.’

He turns and looks up at the stars. He sits down on the cricket pitch for a better angle, looks up and takes in the universe, all that scattered space crystal.

‘You’re right about your mum,’ he says. ‘She’s way too good for me. Always has been. Far as I’m concerned, she’s too good for anyone. She’s too good for that house. She’s too good for this town. Too good for me.’

He points to the stars. ‘She belongs up there with Orion.’

I park my tender arse down beside him.

‘You want to get out of here?’ he asks.

I nod, stare up at Orion, the cluster of perfect light.

‘So do I, mate,’ he says. ‘Why do you think I been doing the extra work for Tytus?’

‘That’s a nice way of putting it. Extra work. I wonder if Pablo Escobar calls it that.’

Lyle drops his head.

‘I know it’s a hell of a way to make a buck, mate.’

We sit in silence for a moment. Then Lyle turns to me.

‘I’ll make you a deal.’

‘Yeah . . .’

‘Gimme six months.’

‘Six months?’

‘Where you wanna move to? Sydney, Melbourne, London, New York, Paris?’

‘I want to move to The Gap.’

‘The Gap? Why the fuck ya wanna move to The Gap?’

‘Nice cul-de-sacs in The Gap.’

Lyle laughs.

‘Cul-de-sacs,’ he says, shaking his head. He turns to me, deeply serious. ‘It’ll get good, mate. It’ll get so good you’ll forget it was even bad.’

I look up at the stars. Orion fixes his target and he draws his bow and he lets his arrow fly, straight and true through the left eye of Taurus and the raging bull is silenced.

‘Deal,’ I say. ‘Under one condition.’

‘What’s that?’ Lyle asks.

‘You let me work for you.’

*

We can walk to Bich Dang’s Vietnamese restaurant from home. The restaurant is called Mama Pham’s, named in honour of the stocky cooking genius, Mama Pham, who taught Bich how to cook in her native Saigon in the 1950s. The Mama Pham’s sign on the front is written in blinking lime green neon against an eastern red backdrop, but the neon ‘P’ is busted and dulled so the restaurant, for the past three years, has looked to passersby more like a pork and bacon–based restaurant named ‘Mama ham’s’. Lyle holds a six-pack of XXXX Bitter in his left hand and opens the Mama Pham’s front glass door for Mum, who slips past him in the red dress and the black heels from beneath her bed. August walks past next with his hair combed back carelessly and his pink Catchit T-shirt tucked into shiny silver-grey slacks, bought from the Darra Station Road opportunity shop seven or eight shops past the TAB down from Mama Pham’s.

The inside of Mama Pham’s is as big as a cinema hall. There are more than twenty round dining tables with lazy Susans spinning for eight, ten, sometimes twelve people per table. Beautiful Vietnamese mums with made-up faces and immovable hair and normally quiet Vietnamese dads loosened and laughing heartily on beer and wine and tea. There are great beasts of the ocean lying sideways in the centre of each table, glazed and oiled and boiled and crumbed and salted and peppered, and whole deep-sea leviathans from the Mekong and beyond, Neptune maybe; big fat awkward bottom lips and slimy tentacle whiskers in colours of green and moss green and blue green and grey green and brown, black and red. Bich Dang owns acres of land at the back of Darra, beyond the Polish migrant centre, with soil like chocolate cake where her old and wrinkled and wise farmers grow the piles of rau ram coriander, shiso leaf, hung cay mint, basil, lemongrass and Vietnamese balm that guests pass between themselves tonight like they’re playing some children’s party game called Hands Across the Table. An oversized mirror ball twinkles above us and a Vietnamese lounge singer twinkles on stage, purple glitter make-up on her cheeks and a turquoise sequined dress that shimmers the way a mermaid’s scales might shimmer beached on the banks of the Mekong. She sings ‘Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft’ by The Carpenters, sways to the crackly backing track, alien somehow, like she just flew into Darra on the kind of craft she’s calling through that old microphone. Red tinsel lines the walls, running above fish tanks with catfish and cod and red emperor and fat snapper fish with balls on their heads that look like someone’s clubbed them with a cricket bat. There’s two more tanks dedicated to the crayfish and the mud crabs who always seem so resigned to the fact they’ll form tonight’s signature dish. They sit beneath their tank rocks and their cheap stone underwater novelty castle decorations, so breezy bayou casual all they’re missing is a harmonica and a piece of straw to chew on. They’re so unaware of their importance, so oblivious to the fact they’re the reason people drive from as far away as the Sunshine Coast to come taste their insides baked in salt and pepper and chilli paste.

A staircase to the right of the restaurant runs up to a second balcony level with ten more round tables where ‘Back Off’ Bich Dang seats her VIP guests, and tonight there’s only one VIP and his name is stretched across the birthday banner running across the balcony rail of the top level: Happy 80th Tytus Broz.

‘Lyle Orlik, son of Aureli!’ Tytus Broz says grandly, his arms raised welcomingly in the air, standing over the balcony rail. ‘It seems Bich has pulled out all the bells, all the whistles and all the stops to celebrate my eighth decade on this good planet!’

Tytus makes me think of bones. He wears a bone-white suit over a bone-white shirt and a bone-white tie. His shoes are brown polished leather and his hair is as bone white as his suit. His body is all bone, tall and thin, and he smiles like a skeleton frame would smile if it hopped off a Biology classroom hook and started to dance like Michael Jackson in the ‘Billie Jean’ clip August and I love like lemonade. Tytus’s cheekbones are round like the protruding balls on the heads of Bich Dang’s tank snapper, but his actual cheeks have been slowly sucked inwards over eighty years on earth and when his lips tremble – and they tremble all the time – it looks like he’s permanently sucking on a pistachio nut, or a vampire bat sucking on a human liver.

Tytus Broz makes me think of bones because he’s made a fortune out of bones. Tytus Broz is Lyle’s boss at Human Touch, the Queensland prosthetics and orthotics sales centre and manufacturing plant he owns and runs in the suburb of Moorooka, ten minutes’ drive from our house. Lyle is a mechanic there, works maintenance on the machines that build artificial arms and legs for amputees across the State. Tytus Broz is the Lord of Limbs, whose vast natural arm reach has stretched across my and August’s lives for the past six years, ever since Lyle landed the Human Touch maintenance job through his best friend, Tadeusz ‘Teddy’ Kallas, the man with the thick black moustache seated four plastic white chairs to the right of Tytus at the VIP dining table. Teddy is also a maintenance mechanic at Human Touch. Teddy is also, I have long suspected, a man with a lucrative on-the-side stream of Tytus Broz’s ‘extra work’ that Lyle spoke of earlier this evening. The man sitting next to Teddy in a grey suit and maroon tie with black hair like a newsreader’s looks a hell of a lot like our local council member, Stephen Bourke, the man who sends us magnetised calendars each year that keep Mum’s shopping lists pinned to the refrigerator. He sips from a glass of white wine. Yeah, in fact, I’m certain that’s our local member. ‘Stephen Bourke – Your Local Leader’ the calendar reads. Stephen Bourke, right here at the table of Tytus Broz, ‘Your Local Dealer’.

The thing about Tytus Broz that reminds me most of bones is that every time I see him – and this is only my second sighting of him – I get a shiver down my spine. He smiles at me now and he smiles at Mum and he smiles at August, but I don’t buy that pistachio-nut-sucker smile for a second. I don’t know why. Just something in my bones.

*

The first time I met Tytus Broz was two years ago when I was ten years old. Lyle was taking me and August to the roller-skating rink in Stafford, on the north side of Brisbane, but on the way he had to drop in to his work at Moorooka to fix a faulty lever on the machine that shaped the artificial arms and legs that paid for Tytus Broz’s bone-white suits. It was the old warehouse back then, before the business was overhauled into the whole Human Touch modern manufacturing plant of today. The warehouse was an aluminium shed the size of a tennis court, with giant ceiling fans to fight the suffocating heat of all that sun-baked metal housing a thousand fake limbs spread across hooks and shelves that led past plaster-makers casting body shapes and mechanics turning screws into fake bent knees and fake bent elbows.

‘Don’t touch anything,’ Lyle ordered as he led us past endless leg limbs standing in a row like a Moulin Rouge can-can troupe miraculously dancing without their torsos. We walked through rows of arms hanging on hooks from the ceiling and these arms had plastic hands that touched my face as we passed and I pictured those arms connected to the bodies of dead Arthurian knights impaled and hanging from long spears in the ground and their hands were reaching out for help that August and I could not give because Lyle insisted we didn’t touch anything, not even the reaching hand of the great Sir Lancelot du Lac. I saw those arms and legs coming alive, reaching at me, clutching for me, kicking at me. That warehouse was the end of a hundred bad horror movies, the start of a hundred nightmares I was yet to have.

‘These are Frances’s boys, August and Eli,’ Lyle said, ushering us into Tytus Broz’s office at the back of the warehouse. August was the taller and the older so he walked into the office first and it was August who captivated Tytus from the start.

‘Come closer, young man,’ Tytus said.

August looked up at Lyle for assurance and an exit out of that moment, but Lyle didn’t give it, he just nodded at August like he should do what was polite and walk closer to the man who was putting the meat and three veg on our table every night.

‘Give me your hand,’ Tytus said from a swivel chair at a red-brown antique work desk. There was a framed painting of a giant white whale above this desk. It was Moby Dick, from what Lyle told me later was Tytus Broz’s favourite book, the one about the elusive whale hunted by an obsessive-compulsive amputee who could have benefited from having a Human Touch prosthetics and orthotics sales centre and warehouse in downtown Nantucket. I asked Slim soon after that if he’d ever read Moby Dick and he said he’d read it twice because it’s worth reading a second time, though he said second time around he skipped the bit where the writer goes on about all the different species of whales found across the world. I asked Slim to tell me the whole story from start to finish and for two hours while we washed his LandCruiser he told me that thrilling adventure tale so enthusiastically I wanted Nantucket fish chowder for lunch and white whale steaks for dinner. When he described Captain Ahab, with his wild-eyed face and his age and his thinness and his whiteness, I pictured Tytus Broz on that whale ship barking at his spotters high up in raging wind, demanding to see his prey, his white whale as white as Tytus Broz himself. Slim turned the LandCruiser into Moby Dick and the garden hose was the harpoon that he stabbed into the whale’s side and we grabbed onto the hose rubber for dear life as the whale dragged us into the abyss and the hose water became the ocean that would take us down, down, down to Poseidon, god of seas and garden hoses.

August offered his right hand and Tytus cupped it gently in his own two hands.

‘Mmmmmmm,’ he said. With his forefinger and thumb he squeezed each of the fingers of August’s right hand, moving his way along the hand, thumb to pinkie.

‘Oh, there is a strength in you, isn’t there?’ he said.

August said nothing.

‘I said, “There is a strength in you, boy, isn’t there?”’

August said nothing.

‘Well . . . would you care to respond, young man?’ Tytus said, puzzled.

‘He doesn’t talk,’ Lyle said.

‘What do you mean he doesn’t talk?’

‘He hasn’t spoken a word since he was six years old.’

‘Is he simple?’ Tytus asked.

‘No, he’s not simple,’ Lyle said. ‘Sharp as a tack, in fact.’

‘He’s one of those autistic boys, is he? Can’t function in society but he can tell me how many grains of sand are in my hourglass?’

‘There’s nothin’ wrong with him,’ I said, frustrated.

Tytus turned his swivel chair to me.

‘I see,’ he said, studying my face. ‘So you’re the talker of the family?’

‘I talk when there’s somethin’ worth talkin’ about,’ I said.

‘Wisely talked,’ Tytus said.

He reached out his hand.

‘Give me your arm,’ he said.

I held out my right arm and he gripped it with his soft and old hands, his palms so smooth it felt like they were covered in the Glad Wrap Mum kept in the third drawer down beneath the kitchen sink.

He squeezed my arm hard. I looked at Lyle, he nodded assurance.

‘You’re scared,’ Tytus Broz said.

‘I’m not scared,’ I said.

‘Yes, you are, I can feel it in your marrow,’ he said.

‘Don’t you mean my bones?’

‘No, your marrow, boy. You are weak-boned. Your bones are hard but your bones are not full.’

He nodded at August. ‘Marcel Marceau’s bones are hard and they are also full. Your brother possesses a strength that you will never have.’

August shot a smug and knowing smile at me. ‘But I’ve got great finger bone strength,’ I said, flipping August the bird.

That was when I spotted the human hand resting on a metal prop on Tytus’s desk.

‘Is that real?’ I asked.

The hand looked real and unreal at the same time. Severed and capped cleanly at the wrist, all five fingers looked like they were made of wax or wrapped in Glad Wrap like Tytus’s felt.

‘Yes, it is, in fact,’ Tytus said. ‘That is the hand of a sixty-five-year-old bus driver named Ernie Hogg who kindly donated his body to the Anatomy students of the University of Queensland whose recent investigations into plastination have been most enthusiastically sponsored by yours truly.’

‘What’s plastination mean?’ I asked.

‘It’s where we replace water and body fats inside the limb with certain curable polymers – plastics – to create a real limb that can be touched and studied up close and reproduced, but the dead donor limb does not smell or decay.’

‘That’s gross,’ I said.

Tytus chuckled. ‘No,’ he said with a strange and unsettling wonder in his eyes, ‘that’s the future.’

There was a pottery figurine of an ageing man in chains on his desk. The ageing man was wearing an Ancient Greek man dress, and had oil paint blood streaks across his exposed back. He was mid-stride, favouring a leg that was missing a foot and bandaged roughly.

‘What’s that?’ I asked.

Tytus turned to the figurine.

‘That’s Hegesistratus,’ he said. ‘One of history’s great amputees. He was an Ancient Greek diviner capable of profound and dangerous things.’

‘What’s a diviner?’ I asked.

‘A diviner is many things,’ he said. ‘In Ancient Greece the diviners were more like seers. They could see things others could not see by interpreting signs from the gods. They could see things coming, a valuable skill in war.’

I turned to Lyle. ‘That’s like Gus,’ I said.

Lyle shook his head. ‘All right, that’ll do, mate.’

‘What do you mean, boy?’ Tytus asked.

‘Gus sees things, too,’ I said. ‘Like Hegesistaramus or whatever here.’

Tytus cast a new eye over August, who gave a half-smile, shaking his head, moving backwards to stand beside Lyle.

‘What things exactly?’

‘Just crazy things that sometimes turn out to be true,’ I said. ‘He writes them in the air. Like when he wrote Park Terrace in the air and I wondered what the hell he was talking about, then Mum came home and told us she was standing at a set of traffic lights while she was shopping in Corinda when she saw an old woman just step right out into traffic. Right out there into the middle of it all, not giving a shit—’

‘Watch your language, Eli,’ Lyle said, cross at me.

‘Sorry. So Mum drops all her grocery bags and takes two steps forward and reaches for this old woman and yanks her back hard to the footpath just as a big council bus is about to clean her up. She saved the old lady’s life. And guess what street that happened on?’

‘Park Terrace?’ Tytus said, eyes wide.

‘No,’ I said. ‘It happened on Oxley Avenue, but then Mum walks this old lady back to her house a few blocks down the road and this old woman doesn’t say a word at all, just has this dazed look on her face. Then they come to this woman’s house and the front door is wide open and one of the old casement windows is banging hard in the wind and the old woman says she can’t go up the front stairs and Mum tries to guide her up there but she goes crazy, “No, no, no, no,” she screams. And nods to Mum like she should go up those stairs, and because Mum has hard and full bones too, she climbs those stairs and she walks into the house and all the casement windows on all four sides of this old Corinda Queenslander are banging in the wind and Mum paces through this house and into the kitchen where there’s a ham and tomato sandwich being eaten by flies and this whole house stinks of Dettol and something darker underneath, something fouler, and Mum keeps walking through the living room, down a hallway, all the way to the house’s main bedroom and the door is closed and she opens it and she’s almost knocked out by the smell of the old dead guy sitting in an armchair by a king-size bed, his head wrapped in a plastic bag and a gas tank by his side. And guess what street this house was on?’

‘Park Terrace,’ Tytus said.

‘No,’ I said. ‘The cops came to the house and they pieced together the whole story and they told Mum how the old woman had found her husband like that in the bedroom a month before and she was so cross at him because he told her he was going to do it but she demanded he didn’t and he defied her and she was so pissed off with him and shocked by the situation that she simply pretended he wasn’t there. She closed the door on the main bedroom for a month, spreading Dettol around the house to mask the smell as she went about her daily business like making ham and tomato sandwiches for lunch. Finally, when the smell got too much, reality kicked in and she opened all the windows in the house and walked straight down to Oxley Avenue to throw herself in front of a bus.’

‘So where did Park Terrace come in?’ Tytus asked.

‘Well, that had nothing to do with Mum. That was Lyle who copped a speeding fine on Park Terrace while driving to work that same day.’

‘Fascinating,’ Tytus said.

He looked at August, leaned forward in his swivel chair. There was something sinister in his eye then. He was old but he was threatening. It was the sucked-in cheekbones, the white hair, the something I felt in my weak bones. It was Ahab.

‘Well, young August, you budding diviner, do please tell me,’ he began, ‘what do you see when you look at me?’

August shook his head, shrugged off the whole story.

Tytus smiled. ‘I think I’ll keep my eye on you, August,’ he said, leaning back in his swivel chair.

I turned back to the figurine.

‘So how did he lose his foot?’ I asked.

‘He was captured by the bloodthirsty Spartans and put in bonds,’ he said. ‘But he managed to escape by cutting his foot off.’

‘Bet they didn’t see that coming,’ I said.

‘No, young Eli, they did not,’ he said. He laughed. ‘So what does Hegesistratus teach us?’ he asked.

‘Always pack a hacksaw when you travel to Greece,’ I said.

Tytus smiled. Then he turned to Lyle.

‘Sacrifice,’ he said. ‘Never grow attached to anything you can’t instantly separate yourself from.’

*

On Mama Pham’s upper floor dining area, Tytus places a hand on each of Mum’s shoulders and kisses her right cheek.

‘Welcome,’ he says. ‘Thank you for coming.’

Tytus introduces Mum and Lyle to the woman seated directly to his right.

‘Please meet my daughter, Hanna,’ he says.

Hanna stands from her seat. She’s dressed in white like her father, her hair is blonde-white, a kind of non-colour, as if all life has been sucked from it. She’s thin like her father.

Her hair is straight and long and hangs over the shoulders of a white button-up top with sleeves running to the hands that she keeps below the table as she stands. Maybe she’s forty. Maybe she’s fifty, but then she speaks and maybe she’s thirty and shy.

Lyle has told us about Hanna. She’s the reason he’s got a job. If Hanna Broz hadn’t been born with arms that ended at her elbows then Tytus Broz would never have been motivated to turn his small Darra auto-electrics warehouse into the home of his fledgling orthotics manufacturing shop which, in turn, grew into the Human Touch, a godsend for local amputees like Hanna, and a source of several community awards given to Tytus in the name of disability awareness.

‘Hi,’ Hanna says softly, giving a smile that would light small towns if it only had more time in use. Mum puts out a hand for shaking and Hanna meets it with a hand of her own raised from beneath the table, and this hand is no hand at all but an artificial limb beneath the white sleeve, and Mum doesn’t skip a beat as she grips that skin-coloured plastic hand and shakes it warmly. Hanna smiles, a little longer this time.

Tytus Broz reminds me of bones because I am all bones and the other man who just caught my eye is stone. He’s all stone. A man of stone, staring at me. He wears a black short-sleeved button-up cotton shirt. He’s old but not as old as Tytus. Maybe he’s fifty. Maybe he’s sixty. He’s one of those hard men Lyle knows, muscular and grim – you could chop him in half and measure his age by the growth rings in his insides. He’s just staring at me now this guy. All this activity around this circular dining table and here’s this stone man staring at me with his big nose and his thin eyes and his silver hair that is long and pulled back into a ponytail but the hair only starts halfway along his scalp so it looks like this long silver hair is being sucked from his cranium with a vacuum cleaner. Slim’s always talking about this, the little movies within the movie of your own life. Life lived in multiple dimensions. Life lived from multiple vantage points. One moment in time – several people meeting at a circular dining table before taking their seats – but a moment with multiple points of view. In these moments time doesn’t just move forward, it can move sideways, expanding to accommodate infinite points of view, and if you add up all these vantage point moments you might have something close to eternity passing sideways within a single moment. Or something like that.

Nobody sees this moment the way I see it, defined as it will be for the rest of my life by the silver-haired creep with the ponytail.

‘Iwan,’ calls Tytus Broz, his left hand on Lyle’s shoulder, pointing at August, who is standing beside me. ‘This is the boy I was telling you about. He doesn’t talk, like you.’ The man Tytus calls Iwan shifts his focus from me to August.

‘I talk,’ says the man Tytus calls Iwan.

The man Tytus calls Iwan shifts his eyes to a glass of beer before him, which he then grips tightly with his right hand and brings slow as a chairlift to his lips. He drinks half the glass in a single sip. Maybe the man Tytus calls Iwan is actually two hundred years old. Nobody’s ever been able to cut him in half to be sure.

Bich Dang approaches the table, calling from afar. She wears a sparkling emerald gown that hugs her torso and legs all the way to her hidden feet so when she walks across Mama Pham’s upper-floor dining area it looks like she’s hovering over to our table. Darren Dang shuffles over in her wake, visibly troubled by the smart black coat and pants he’s not so much wearing as enduring.

‘Welcome people, welcome, welcome, sit, sit,’ she says. She puts an arm around Tytus Broz. ‘Now I hope you have brought your appetites. I have prepared more hot dinners for tonight than this one has had hot dinners.’

*

Points of view. Vantage points. Angles. Mum in her red dress, laughing with Lyle as she drops chunks of crispy tilapia onto her plate. The tilapia has been drowned in a garlic and chilli and coriander sauce, so many exposed white bones in its charred and thorny dorsal fin that they look like the ivory keys in the warped piano organ the devil plays in hell.

Tytus Broz resting an arm over his daughter, Hanna, as he talks to our local member, Stephen Bourke, who wrestles with a chopstick clump of Vietnamese lemongrass beef noodle salad.

Lyle’s best friend, Teddy, staring across the table at my mum.

Bich Dang bringing another dish to the table.