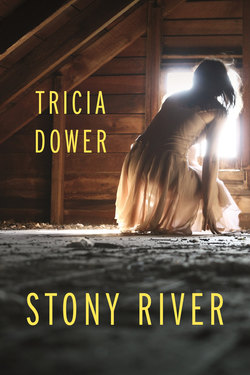

Читать книгу Stony River - Tricia Dower - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSummer Solstice 1955

The river crooked its finger at her.

Linda crab-walked down the treacherous bank, taking care not to slip. She didn’t dare go home with mud on her behind. A swallowtail’s flutter made her jump, the call of a tree frog. Strides ahead, her new friend Tereza was carving a path through tall, hairy milkweed.

The Stony River meandered for miles through a dozen New Jersey towns like this one, passing through woodlands and wetlands, salt marshes and tidal flats. Once upon a time, it harbored creatures with astonishing names like diamondback terrapin, alewives and cormorants. Now you were more likely to find rusty car fenders and stinky chemical foam.

Daddy told of swimming in the river when he was a boy, of the whole town turning out for canoe races past bridges decorated with paper lanterns. Mother told of lying awake at night after Pearl Harbor, sick with worry the Japanese would skulk up the river, signaling each other with jars of lighting bugs. Two boys drowned one winter, the ice breaking as they slid across the river, their frozen bodies found with sad little arms outstretched. If caught anywhere near the river Linda would be banished to her room without dinner and there’d be one more black mark against her on Judgment Day. Honor thy father and thy mother. But on that sticky hot afternoon, when Tereza said, “Let’s go smoke punks at the river, it’ll be cooler there,” she said, “Sure.”

Tereza did whatever she wanted, maybe the difference being she was thirteen and Linda two months shy of twelve. Or maybe because, as Mother said, “There’s more than a little gypsy in that girl.” All Linda knew of gypsies was that they got to play tambourines and trek around exotic lands in painted wagons strung with pots and pans. Tereza’s family rumbled into the neighborhood two weeks ago in a rusting blue truck, choc-a-bloc with boxes, mattresses, a bicycle and furniture odds and sods. They’d lugged it all into the ground-floor apartment of the two-story building across the street and two doors down from Linda’s house. The building housed a corner store to which Mother sent Linda when they ran out of bread and milk, not wanting to go there herself because it was “seedy.” Daddy said it had just been neglected. Linda tried not to feel superior to Tereza for living in a tidy bungalow with green siding and its own yard. Judge not, that ye be not judged.

What Tereza called punks were cattail flowers that looked like fat cigars. To get to where they grew, the girls had scampered down a narrow road past Crazy Haggerty’s house, the biggest and creepiest in the neighborhood, its once white paint weathered to gray. It sat high above the water with no other houses around. The drapes were drawn tight, not a window open to catch a breeze. Linda wondered if Haggerty was in there watching. She’d only ever seen him on her way home from school. He’d be heading toward town, weaving back and forth, always wearing the same red shoes and satiny black suit with sequins. He’d scowl if you gawked, tell you to get lost. Mother said to steer clear of him. Daddy said the poor man seemed tortured.

Reaching the river’s edge without a tumble, Linda released a breath and lifted her gaze from her feet to brown water as sluggish as the air. Bright green slimy globs lazed on the surface. She couldn’t picture Daddy swimming in that.

Tereza held her nose. “Smells like sweaty socks, don’t it?”

Linda grunted in response. When the wind was right, she would catch whiffs of the river on her way to school. The sometimes sweet, sometimes rotten smell of mystery lurked behind houses grander than hers with plush green back yards leading to wooden docks and rowboats. But this close to the water, the smell was almost indecent, more like soiled underwear than sweaty socks.

Tereza pulled a penknife from her pocket and cut a couple of punks, leaving short stems. She produced a small box of wooden matches. The punks weren’t dry enough to flame up and she wasted a couple of matches before they caught and smoldered. “Mmm,” she said, waving her punk under her nose, “I’d walk a mile for a Camel.”

Linda hid herself behind a bush and held her punk down by her knees so the smoke wouldn’t give her away. She stuck the thin, hard stem in her mouth and puh-puh-puhed as she’d seen Daddy do to get his pipe going. The stem tasted like potato peel.

Tereza snorted. “Ain’t nothing to inhale, genius. This your first punk?”

So what if it was? “Of course not. It’s just more fun this way.”

Tereza puh-puh-puhed, too, then sucked on the stem so hard her eyes crossed. “No it ain’t.” She plopped on the ground without a care for the mud.

Linda kept crouching, though her knees and thighs had started to burn. “What should we do this summer?” Tereza was the only girl even close to her age on the “right” side of the highway Linda wasn’t allowed to cross alone. Tereza moving in was like finding an extra gift under the Christmas tree.

“I don’t know. Hang out. Play baseball. I seen a couple cute guys at the store.”

Hoods. Rude boys who made Linda feel ashamed for simply being a girl.

Tereza was first to spot the police car as it crept down the street. “Shit.” She snuffed out her punk and spidered up the riverbank, Linda right behind her. Both girls wore pedal pushers but Tereza looked better in hers. Her skin was the color of a root beer float and her body wasn’t lumpy. Linda squinted. She’d left her ugly glasses at home but she could make out two shapes in uniforms emerging from the car. They scaled the hilly lawn to Crazy Haggerty’s and took the steps to the wraparound porch. One was stout enough to be the crotchety officer who gave talks at school on what to do if someone tried to force you into a car. All Linda could ever remember was to scratch the license plate number in the dirt with a stick. What if there was no dirt, no stick?

“Somebody must’ve got bumped off.”

“No one gets murdered in this boring town,” Linda said.

• • •

The dog has abandoned his post at the foot of the lad’s bed.

He bounds down the once fine staircase to the shadowy front entrance where Miranda stands awash in her own fear. His growl is a deep rumble she feels through her bare feet. Nicholas wouldn’t be growling if the footsteps belonged to James. And James wouldn’t be coming in the front. He’d be shuffling through the back where Miranda has looked for him off and on since last sunset, slipping up and down the stairs, stealthy as a shadow, risking more than one furtive glance under the back door window shade. She’s had to keep the lad amused on her own and cope with Nicholas doing his business all over the house.

James never leaves her overnight. And they’ve not been apart, before, on Summer Sun Standing: the day of the year the sun stands still before retracing his steps down the sky; when night holds her breath, beguiling you, for a moment, into believing mortal life can exist without death. James should be here, dancing with her on the summer king’s tomb.

Nicholas’s growls become short sharp barks as one pair of feet and then another reach the porch. Miranda’s Veranda James named it when she was learning to rhyme. He tells her she trod on its boards when they crossed the threshold. She doesn’t remember. She was three.

Strangers knock from time to time. Most leave quickly after hearing the dog. Not these. Nicholas hurls himself against the ponderous oak door so violently it shudders. The impact throws him to the floor. Miranda winces, feeling his pain in her shoulder and hip.

“Police!” A clean, hard voice, not breathy and musical like James’s. “Anyone home?”

Nicholas’s nails click against the pegged wood floor as he scrambles up, readying himself for a second assault. If James were here, he’d retrieve his shotgun from the closet and make sure she and the lad were hidden.

The doorknob rattles. She ponders the lock and the long black key she’s never turned.

Should they appear one day when I’m away, James said, welcome them a thousand times over but deny all knowledge. She closes her eyes and summons the memory, hoping to extract more guidance from his words, but the memory gets lost in the dog’s barking and the mewling of the lad upstairs, who has woken to find Nicholas gone.

Is there still time to hide?

The door shudders again, this time from pounding on the outside. “Anyone in there?” Louder now. “Don’t make us break the door down and shoot the dog.”

Miranda drops to the floor next to Nicholas and wraps her arms around his quivering body. He smells of decay. His heart thumps so hard she fears it will burst.

“Breathe my air,” she whispers.

He licks her face, his tongue hot and frantic. He’s already lapped up more than his measure of years but she can’t bear the thought of anyone shooting him.

“Open up!”

One arm about the dog, she drags him with her as she sidles on knees to the keyhole. Pinches and turns the key with thumb and forefinger until she hears the click. Stands and grips Nicholas by the ruff. She pulls open the door enough to detect two bodies, one near enough to touch. Muggy air infiltrates the entryway.

“Good day,” she says, summoning the courage of Alice facing the Queen. But her voice comes out as thick as cold treacle and her legs go weak. Nicholas howls and a gun materializes in the closer man’s hand. Miranda presses her free hand against the wall to steady herself. “Silence,” she hisses. Nicholas obeys.

The man with the gun says, “This Mr. James Haggerty’s home?”

“Aye.” In twelve years she has spoken only to James, the lad and Nicholas. She knows not how much or how little to say.

“This your home, too, Miss?”

“Aye.”

He inhales sharply and says to the other man, “Thought they said he lived alone.” He turns back to her. “We have news. Are you able to control the dog?”

She points and firmly says, “Nicholas, go.”

He backs up through the dining room into the kitchen and, with an extravagant sigh, slumps to the floor by the wood stove, in eyeshot of the door.

Miranda’s arm shakes as she opens the door a smidgen wider and blinks into unfamiliar daylight. The one who spoke is tall and wiry, younger than James but clearly a man, a beautiful one, garbed in black trousers and a white short-sleeved shirt bearing a shiny metal emblem. Miranda would like to stroke the light brown hairs covering his arms. Although she means to admit only him, the second one, dressed the same, slides in behind. He’s older and potato-shaped, a gun belt hanging low under his belly.

“Should we wait while you cover up?” that one asks. She shakes her head. On sweltering days she always wears her mother’s white cotton petticoat if she wears anything at all.

The men remove their hats, revealing hair damp with perspiration. They exchange looks she cannot decipher. “It’s dark in here,” the tall one says. The house is illuminated only by sunlight splintered through gaps in the midnight-blue drapes drawn full across the windows. The older man finds a switch on the wall, flicks it up and down.

“Power out?”

“We use candles.” She doesn’t offer to squander any so early in the day. She anxiously follows the tall one’s gaze to the room on his right with the mahogany table where they eat and she does her sums, and then to the library, on the opposite side of the entryway, where she and James play the windup phonograph and he reads to her of ‘a time before time.’ She sees nothing a spy could report. Our way of knowing isn’t wrong, James has said, but others fear it and therein lies the danger for us.

The tall one’s ears stick out like handles and she stares at them frankly. Curiosity instructs, James likes to say, and a sense of wonder is a gift. Is it wonder or dread making her draw a jagged breath? The house has shrunk with the men in it. They’ve swallowed all the air.

The tall one dips his head, smiles and says, “Officer Nolan, Miss. Don’t be afraid. We won’t bite.” He shows her a thin black billfold with his photograph and name. “My partner here’s Officer Dunn. That a baby crying?”

“Cian!” The lad’s old enough to climb from his cot but he’s never tried. James says it’s a sign of Cian’s advanced trust in the universe to provide for his needs. She starts toward the staircase and the one named Dunn says he’ll go with her. She turns back and searches his moon pale face, his small cold eyes. “You’ll vex him,” she says.

“Where’re you from?” Dunn asks. “You talk strange.”

How to answer? She speaks like James. The officers are the strange-sounding ones. Dawg. Tawk.

“How ’bout you radio the station, Frank?” Nolan nods toward the door. “Let ’em know what’s up.” Officer Dunn leaves.

She climbs the stairs and hurries down the hallway to Cian, who’s rattling the bars of his cot and bleating. “Mandy!” he cries, his mouth pitifully distorted. He stands in his cot, hiccupping little sobs. A sodden nappy rings his ankles. Ammonia from it and others in a nearby bucket stings her eyes. His fair hair is sweaty, his wee organ an angry red from rash. When James left yesterday, he said he’d return with the ingredients for a healing salve.

“Mandy’s here, poor biscuit.”

If she had the lad’s trusting nature she’d chance opening a window in hopes of a cooling breeze. If she didn’t fear exhausting the drinking water, she’d bathe Cian and launder his nappies. Fear is the mortal’s curse, James says. Look at me, so dreadfully afraid of losing you. She lifts the slight child, shaking the wet nappy from his feet. She carries him down the stairs.

Nolan peers up from a notepad. His eyebrows lift. In surprise? Dismay? For a moment she forgets to wonder why he’s here. Perhaps he isn’t. It’s easy to imagine herself, James and Cian as the only souls alive. She heads for the burgundy horsehair sofa in the library. As she sits, dust motes rise in a slow dance and drift back down. She drapes Cian across her lap and wriggles one arm free of the petticoat. He clamps his mouth on her breast, wraps a spindly arm about her waist. His head is warm and damp in the crook of her arm.

Nolan remains in the entryway. To see him, she’d have to wrench her head around. “So the child is yours?” he says. “You look too young.”

In three years, when she’s eighteen, nobody can wrest her from James. She will stand beside him under a ceiling of stars while he invokes the mighty ones. When she’s eighteen, she’ll venture out on her own for Cian’s earthly needs. James won’t have to bring her lilacs each spring. She’ll seek them where they grow and drown her nose in their drunken scent, lie on soft grass, garbed in gossamer and sunlight. She will climb Merlin’s oak tree and Heidi’s mountain, row a boat down the enchanted river behind the house, tread on hot sand and sing as boldly as she wants without worrying someone will hear. She and Nicholas will lope over carpets of dandelions as they do in her dreams. Lope is a word she likes to say out loud for the way her tongue starts it off before disappearing behind her lips.

“You say you have news?”

“Yeah.”

She hears him inhale deeply, hears his belt jangle as he shifts weight from one foot to the other. “Mr. Haggerty died on the three-forty-two from Penn Station yesterday,” he says.

“What’s a three-forty-two?”

“You serious?” When she doesn’t answer, he says, “A train.”

“Did he jump?”

“Why would you even think that?” He jangles again.

“Anna Karenina did.”

“Who?”

“A woman in a book.” The longest she’s ever read, one James challenged her to get through, hoping to seduce her from the youthful fantasies she prefers. “But truly, truly, it’s not my fault, or only my fault a little bit,” she says aloud, trying to say it daintily like Anna.

Nolan releases a short, tuneless whistle and says, “Jeez, it’s stifling in here. How can you breathe?” His shoes squeak behind her as he goes to the window and pulls back the drapes. He grunts with the effort of hoisting a sash that’s not been lifted since the lad was born for fear his cries would be heard. Panic rises in her throat, a reflex. She tenses, ready to flee upstairs with Cian until she remembers it’s too late to avoid detection.

“Okay if I take a seat?” He’s at the chair on her left.

She nods and he sits, his face in profile, his gaze averted. She runs an imaginary finger over the small bump on his long nose as he hangs his hat on one knee. World scents cling to him, as they do to James when he’s been out. She likes to guess at them, surprising James with her accuracy. Nolan smells of leather and smoke.

“Several passengers witnessed him collapse and die. The coroner determined it was a heart attack. He won’t order an autopsy unless the family insists.”

She focuses on the far wall near the fireplace on a spot where the floral wallpaper is peeling, envisions an angry heart with arms and legs leaping from James’s chest and stabbing him with a fork. Her own chest begins to ache. Pain is an illusion, James says. Float above it. She stares at the dangling wallpaper strip and floats as far as the anchor of Cian’s rhythmic sucking on her nipple allows.

Nolan glances at her then quickly looks down. “You okay?”

“Aye.”

It will storm tonight. She can tell from the weight of the air pressing in through the open window. Thunder will prowl the sky and Nicholas, the house. Lightning will crackle outside the room she shares with Cian and they’ll both cry out for James.

Later, Bill Nolan will tell his wife the girl’s composure was unnerving. No sign of grief as she sat brazenly nursing that naked, emaciated, shrunken-headed child on a couch with lion-clawed feet. He will file a report that says Miranda Haggerty is disturbingly detached and possibly slow-witted.

“Has he started walking yet?”

“Oh aye.”

“I ask because he seems weak.”

She unhooks Cian from her breast and sits him up on the couch. “Will you walk for the man, then?” The lad widens his hazel eyes at the officer then hides his face in her shoulder. “He’s not seen the likes of you before,” she says.

“The uniform, I suppose. You take him out, right? The park, the doctor’s?”

Why doesn’t the officer leave, now he’s delivered his news? She pulls the strap back over her shoulder, tucks in her breast and lifts her hair from her perspiring neck. She doesn’t lie but she’s learned to remain silent when it suits her.

Nolan stares at her straight on, his cheeks flushing, his Nicholas-brown eyes intense. “I’ve got a three-year-old daughter and my wife’s expecting again. We’re hoping for a boy.”

“Why is that, now?”

“I don’t know.” He laughs self-consciously and rubs the back of his neck. “Don’t most men want sons to carry on their names?” He clears his throat and straightens his spine. “Who’s your boy’s father?”

Some mysteries cannot be expressed in words to the unready, James says, for they will not be understood. She is sworn to secrecy for the child’s sake. She peers down at Cian clinging to her and softly sings his favorite song: “There was an old man called Michael Finnigan, he grew whiskers on his chinnigan.”

Cian lays a finger on her mouth and says, “Mandy.”

She sucks in the finger and he laughs, a deep chuckle that threatens to loosen her fragile hold on the tears pooling behind her eyes. Without James, who will guide Cian to his calling? Who will brush her hair?

Nolan pulls his notepad from his shirt pocket. “That your name? Mandy?”

“Only to the lad.”

He slaps the notepad on his open palm, an angry sound that jolts her. “I’m trying not to push you but I need more to go on, here, Miss Whoever You Are, more than you’re giving me.”

James flashed with impatience, too, yesterday morning, when she asked would he bring back strawberries. “I cannot cover the sun with my finger, can I?” he said.

Well, she, too, can be stroppy. “How are you knowing the dead man is James?”

“He had a library card with him.” Nolan glances at the bookshelves lining two walls. “Seems he liked to read.”

The card was for her benefit. Most books on the shelves were published before Miranda was born. They don’t hold all James wants her to learn. “I mean to see him,” she says. The dead man might have stolen that card. James could be in a public house right now, performing card tricks for drinks.

“I can arrange that, provided you’re next of kin.”

His words call up a line from a book forgotten until now: It is understood that the next of kin is Mr. Henry Baskerville.

“James is my father,” she says, thinking how deficient a word is father. “My mother passed over years ago and there’s no one else.” She thinks on her mother’s parents, brothers and sisters all perishing in their summer cottage when it was swept out to sea by a fierce storm two years before Miranda was born. James spoke of it only once because she trembled and cried for days afterward, imagining herself tossed about and pelted by flying crockery. If there be family alive in Ireland she doesn’t know of them.

Nolan is quiet for a moment. Then, “That’s rough. I’m sorry.” He reaches over and pats her knee, sending a shiver of longing through her. “There a priest or minister I can call for you?”

She shakes her head. James says a soul’s journey needs no priest, no mediator.

“An unusual name, that—Key-uhn. How’s it spelled?”

She tells him and, sensing the need to offer more, adds, “It means ancient one.”

“You and the boy can’t stay here by yourself,” he says, putting words to the terrible truth creeping into her mind: only James knows where the money tree grows, how to find food, bless the well, chop wood.

“And where shall we go?”

“Children’s Aid will find you a family, might take a day or so.” He spins his hat around in his long-fingered hands. “You can stay at my house tonight, at least.”

She cannot recall being anywhere but here.

“I don’t suppose you have a telephone,” he says.

“We do not.” Or anything else that would allow a tradesman access to the house.

“Did your father have an employer we should contact?”

“He did not.”

“Will you be okay if I leave you a few minutes to radio the station? I should let my wife know you’re coming.”

She nods and stands with him, follows him to the door and watches it close behind him. With both men outside, now, she considers locking it. The family they found for Jane Eyre treated her badly: You ought to beg and not live with gentlemen’s children like us.

She’s never tried to leave their house before, though she could have easily. James locked the back from the outside when he made his forays into the World but he always left the key inside the front door. Finding her gone would have shattered him after all he’d forfeited for her: a professorship, old mates, traveling to his mother’s wake. She could never be that ungrateful.

Her mind flies through each room of the house. The windows facing the back are shuttered from the outside. The small window on the back door at the bottom of the kitchen stairs isn’t. She’d have to smash it, drag a chair down the stairs to the landing, stand on it and crawl out. Push Cian through first and drop him to the ground. Would the officers hear? Would Cian get hurt? And Nicholas, how could she leave Nicholas? Her mind is surveying the upstairs when Cian lets out a high-pitched cry. She turns to see him toddling toward her, clutching his groin and dribbling urine. His face twists in pain. She scoops him up, rocks him in her arms and softly finishes the verse, “The wind blew up and blew them in again. Poor old Michael Finnigan.” He smiles up at her with such love and trust she can no longer dam her tears. She carries him into the kitchen and crumbles to the floor next to Nicholas, who licks her salty face.

There’s naught to deliberate. She must accept Nolan’s help.

He and Dunn return with two sweaty-faced men and contraptions for which she has no words. To catch and contain Nicholas, they explain, so they can transport him by truck. He can’t ride with her and the child, they say in response to her question. Not enough room. No, the cage isn’t cruel. It will prevent him from being thrown about the truck and getting hurt. She doesn’t know how else to resist.

The net isn’t needed. Head down, tail drooping, Nicholas meekly enters the cage when she directs him to. “Anon,” she tells this creature she has loved from the time they stood nose to nose. He refuses to meet her gaze.

Nolan suggests she dress the child and clothe herself in something “more suitable.” She remembers a worn valise in James room and tiptoes in to get it, half expecting him to be there and scold her for entering his private space. She chooses a dress her mother once wore and packs two others, along with rags and cotton drawers for her bleeding times, the petticoat, three handkerchiefs, heavy stockings, flannel pajamas, a woolen jumper, clean nappies and the bits of garb James has managed to acquire for Cian. She dresses the lad for the heat, in a white cotton singlet and nappy.

“Sure we never needed them,” she explains, when Nolan inquires about coats. He frowns and scribbles in his notebook. The lad has no shoes but she manages to squeeze into her mother’s open-toed high heels, the ones she played glass slipper in when she was younger.

Dunn asks about birth and death certificates, wills, the deed to the house and other “relevant documents.” If any exist, they’re in the locked desk in James’s room, a possibility she doesn’t mention, partly because Dunn is gruff and presumptuous but also because she doesn’t know what else might be there James wouldn’t want them seeing.

No room for the books, the phonograph and records, they tell her. Someone will collect them for her later. After having lived in this house so long with the days stretched out before her, she’s rushed now into leaving. She packs Cian’s Peter Rabbit bowl and the small flannel blanket he sucks on at night, her lexicon, a pencil, a moonstone, a white candle and matches, her hairbrush and a drawing James made of the goddess Ethleen holding the moon—a milky-skinned, dark-haired woman wearing a gown of starlight. For as long as Miranda can remember, the drawing has hung over her bed as proxy for her mother. She says anon to the walls, floors and ceilings and all who lodge within them, wondering who will hear their scratches and whispers in the night until she returns.

• • •

Tereza’s ass was sweating. She’d rather have been puffing cigs with the guys who hung out at the corner store in her building but they weren’t around. She was stuck with a kid who looked like Tiny Tears with those blond curls and chubby gut. The only cool thing about Linda—sandals with laces that crisscrossed her ankles like a Roman soldier’s—was also the only cool thing about a Jesus movie Tereza had gotten rooked into seeing by a dumb girl the last place she’d lived. When Tereza became a star, she’d say uh-uh to movies that made you feel like you had to be “saved” from yourself. She liked sci-fi thrillers where the entire earth had to be saved from total destruction. She wasn’t keen on most girls, either. They didn’t know as much as guys about things that mattered. Take Linda: she didn’t know shit about the river even though she’d lived only blocks from it her whole life. And she was scared of too much to be any fun.

Tereza would have split by now if the cop car hadn’t shown up. She’d almost crapped her pants when it did, thinking Jimmy had gotten home early and sicced the cops on her for leaving Allen alone while Ma was out looking for work. Then it occurred to her the last person Jimmy would want to see was a cop.

A Charlie Chan mystery was going on in Crazy Haggerty’s. Two cops had clomped into the house, come out one at a time and parked themselves in their car for a while. Then dogcatchers showed up in a white truck, went in with the cops and came out with a black German shepherd. Tereza would’ve liked that dog. Jimmy wouldn’t be so fast to smack her with Rin Tin Tin at her side.

It was ages before the short cop waddled out the front door carrying a small, tan suitcase. The tall one followed, holding the elbow of a girl with cocker spaniel hair down to her waist. The girl wore high heels and a navy blue dress with white polka dots. On her hip she held a puny kid with a freak-show-small head. The girl looked like she might know a thing or two.

“Who’s that?” Tereza asked real low.

“Somebody visiting Crazy Haggerty, I guess,” Linda whispered.

“What’s wrong with the kid?”

“How would I know?”

The girl turned and stared straight out to where Tereza and Linda were hiding. It made Tereza shudder. The kid looked starved. Maybe the cops were taking the girl to jail because of that. Jimmy used to threaten her with jail before she figured out she could scare him worse with it. He told her the cops would pull her fingernails out with pliers and parade her around naked.

A sudden dread for the girl brought her to her feet. “I’m gonna find out what’s going on.”

“No!” Linda yanked the back of Tereza’s pants and pulled her back down. “They might tell on us. I’ll get in trouble.”

“With the cops?”

“No. My folks.”

“What’s the worst they can do to you?”

“You can’t imagine.”

Tereza hadn’t spotted a single scab or bruise on those rubber doll arms and legs but maybe Linda’s old man and lady weren’t as harmless as they looked.

Tereza dropped back to the ground. “My brother’s a big chicken, too.”

Linda’s face collapsed like a squashed Dixie cup. Tough gazzobbies. Tereza couldn’t babysit everybody’s feelings.

• • •

For twelve years Miranda has viewed the World through the attic’s streaky window, seeing half a tree, a snip of street and only the birds and clouds that pass by her scrap of sky. Being at one with nature is our birthright, James said. Depriving her of that pained him. Daylight makes her eyes water. And the smells! She feels dizzy. Focus, James would say. Imagine yourself the circus tightrope walker he described seeing as a child—taking slow, deliberate steps, placing one foot carefully before the other.

She wants to touch the tree whose branches scratch the roof and hug the earth. But Nolan leads her to a black car with two white doors. She balks as Nolan opens a door for her. Is the car any less a cage than that holding Nicholas? Then she recalls the professor’s nephew who feared entering the volcano, at first, nearly missing out on that incredible journey to Earth’s core. She ducks her head inside. Cian squeals when the engine erupts but bounces excitedly on her lap as they pull away. Twisting to see through the rear window, Miranda watches the home she hasn’t seen from outside since she was three shrink and grow faint.

• • •

Tereza hacked off two more punks and handed one to Linda. “If you smoke it down to the end,” she said, “sap will fizz up into your mouth.”

Linda screwed up her nose as if Tereza had farted. “Revolting.”

Tereza turned away and studied the old house. One thing she always did in a new town was suss out possible hidey-holes. No sign of Crazy Haggerty and the dog was gone. If the house turned out vacant for sure she’d come back and prop a window open in case she needed to get in someday. Bordering the neighborhood were the river, a farm and the highway her family had taken all the way from Florida. In the middle were houses, empty lots and trees. The farm had a haystack big enough to hide a girl but a vacant house would be better when the weather turned cold. Across the highway were a zillion other possibilities. Right now, though, Crazy Haggerty’s house was boss. She’d sneak back to it after dark.

• • •

As the car gathers speed, a hot breeze from the open windows lifts Miranda’s hair and slides under her dress. Curious wonders pass by so quickly they become blurs of color, so many shades of green, yellow, brown, blue and red. Cian, frightened and delighted at once, clings to her neck with one arm. He points with the other and babbles, attempting to name all he sees. Each dog is “Nicko.” Closing her eyes when sights overwhelm her makes her queasy. Fixing her gaze on the back of Nolan’s head helps but, even so, she’s bilious and disoriented by the time they arrive at a building Nolan informs her is the hospital.

Dunn deposits them at the entrance. Carrying her valise, Nolan leads them through a door made of glass (imagine!) into a large room with sofas, chairs and an illuminated ceiling. Someone approaches them. A woman, she realizes with a thrill. A woman who rises on the toes of her flat black shoes and kisses Nolan on the cheek.

“Thanks for being here,” he says to her. “Where’s Carolyn?”

“With Mom. She’ll keep her as long as we need.”

“Ah, she’s a peach.” Turning to Miranda, he says, “My wife, Doris.”

Doris has tightly curled black hair and a swollen stomach under a long white shirt: a mother goddess at full moon. Her black trousers stop mid-calf. Doris captures Miranda’s free hand with her two small ones. Her smooth hands are pink against Miranda’s candle-white skin, her pursed lips painted the color of fresh blood.

“You poor thing,” she says.

Panic flaps its wings inside Miranda’s chest as Nolan excuses himself to check on arrangements for viewing James’s body. She no longer wants to see a corpse. About her come and go more people than ever she’s seen. Voices from nowhere say words she can’t decipher and invisible chimes go bing-bing. She misses the slow, predictable rhythm of the house, wants to chase after Nolan and ask would he take her home. But Doris, smelling like dried wildflowers, steps even closer and shines a smile on Cian.

“What’s your name, little guy?”

Miranda answers for him. Cian isn’t one of the five words he can say.

Doris mispronounces it as a single, reverent, syllable: “Keen. That’s a new one on me. How old is he?”

“One year and four months.”

“I would have guessed younger.”

Miranda lays a hand on Doris’s melon-hard stomach.

Doris quicksteps back then catches herself and smiles. “Three more months.” She extracts a red tubular object from a large blue and white checked cloth bag. “Say, Keen, do you like kaleidoscopes?” The lad frowns and sniffs it, puts his tongue on it. She laughs. “No, no. Look into the eyehole. Here, let me show you.” Softly, almost mouthing the words, she asks Miranda, “Can he understand?”

“And why wouldn’t he?”

“Well, I wasn’t sure, given his condition.”

“There’s no want in him,” she says as James answered her when she wondered if the lad was like other children. James said naught about a condition.

Doris succeeds in getting Cian to peer into the tube and hold it by himself. “Oh, you’re clever.” She sets her bag on the floor and opens it wide. “I have more toys. Want to see?”

“See,” Cian says. Miranda sets his bare feet on the floor. He toddles to the bag and reaches in as though he’s done it forever, pulls out a block with the letter Y.

Nolan returns and says to Miranda, “Whenever you’re ready.”

Doris bends her head to touch Miranda’s: a silent benediction. “Go on,” she says, her voice as soft as dusk. “He’ll be fine with me.”

• • •

Their footsteps resound as Nolan leads Miranda through double doors and down a hallway smelling like pinecones. At the end, a blue door opens to a narrow windowless room with a red floor, a yellow chair beside a gurney. Her toes in the open shoes recoil at the cold. She shudders.

All the dark was cold and strange.

“It’s called the cooler,” Nolan says. Another word for her personal lexicon.

They move from doorway to gurney. Tightrope walking again, a thunderous pounding in her head. She stares, unseeing, at the white tiled wall before her. Nolan says, “Jeez, they usually clean them up.” He guides her to a spot in front of the chair. Asks for “a positive eye-dee.”

She slowly lowers her gaze and sucks in a breath. The body on the gurney is rigid, its face and neck the color of moldy bread, the mouth frozen into an O, the eyes open in surprise. The carapace of a life reborn in the Other Life.

So this is what death looks like.

She finds the frigid chair with the back of her legs, sits herself down and says, “Aye, ’tis James.” She knows that shiny black suit with the satin lapels and frayed cuffs, the theatrical red shoes. His Mad King Sweeney outfit, he called it.

He’d make his hair and eyes wild and say, “Tell me, is this a look that would sour cream?” He wanted people to think he was gone in the head so they’d stay away from him and not find out about her. “We are the gods’ hidden children,” he’d say, his voice defiant and proud.

The suit is wet in spots, as though he’s leaking. His cheeks have sunk into his face. Terrible strange flecks lodge in his moustache and beard. She studies his chest, half expecting its rise and fall, sees her child self crawl into his lap and fall asleep to his thumping heart.

Nolan says, “I’ll be right outside.” The door closes on the silent cold.

She reaches out and lightly touches a hand, bloodless on top, deep purple where it rests on the gurney. The fingers curl under as though they died scratching the earth. His skin is as alien as the chrysalis he once carried home to demonstrate life follows death as surely as morning, night. “One day I will shuck this shell,” he said that day, “and emerge on the other side fluttering and swooping among flowers so beautiful they forbid themselves to grow here.”

She wept at that, unable to imagine life without him. Being human is incomplete, he explained, disappointed she couldn’t see that. He could leave his body at will but a craving for whiskey held him back.

Until now.

She swallows a deep breath, holds and releases it, trying to channel his energy. She drinks more air, holds and releases it. She listens with ears and heart.

She’s never matched his concentration, never lifted the physical veil. Someday, he said, she’d summon the will to let the power enter her. Then she’d be ready to accept the legacy of her grandmother and great-grandmother, who taught him to call forth summer and winter on the harp he was to have played for her this day of summer sun standing.

She rises from the chair and sniffs his length. Unwashed hair, stale sweat, urine and feces: the smell of a body abandoned and a vow forsaken. He’s left her alone to care for the child. She and the lad were no longer enough to tether him to the World.

“Couldn’t you wait?” she cries out. She hugs herself to stop her arms from shoving him off the gurney and squeezes until she feels her pulse beneath her fingertips. Empties herself of tears then leans over him until her swollen eyes are level with his deflated ones.

He isn’t in there.

She whispers what he had her say each morning: “I am the same and not the same as I was before.”

“As tonight’s moon will not return tomorrow,” he’d say, “you will emerge altered after each night’s sleep, after each book you read, after each moment you experience.”

She tugs out a strand of his ginger hair for herself and removes the red shoes for Cian. Gives thanks for the hallway’s warmth and for Nolan leaning against the wall.

“Shouldn’t he be buried in those?”

“A butterfly won’t be needing shoes.”

In a small room with a narrow table and two chairs, Nolan records her answers on a Death Information Form. James Michael Haggerty: born March 3, 1907, County Meath, Ireland. Spouse Eileen Reagan Haggerty: born October 10, 1918, Milford, Massachusetts, deceased January 7, 1943, Providence, Rhode Island. Miranda knows these places only on maps but their names, along with the dates, are bound into her memory from a page in a book James kept, inscribed with his flourishes, his script more beautiful than hers despite all her practice. Providence is where James said he met Eileen. He was a visiting professor at the university for which she organized collections of scholarly books and papers.

The Form demands the deceased’s children’s names and birthdates.

“Miranda Brighid Haggerty,” she recites, “May 12, 1940, Providence, Rhode Island.” She was named after Prospero’s daughter and a Celtic goddess. Nolan writes the goddess’ name as she pronounced it—Breege. She doesn’t correct him. He waits a moment. “And Cian?”

On a mattress with James saying, “Float, float,” as Danú possessed her womb.

“Miranda will suffice.”

James catching Cian. The pulsating cord, the bloody placenta.

A tight-lipped smile. “We’ll have to talk about that eventually. Father have insurance?”

“Sure I don’t know.”

“No matter. The city will bury him.” He hands her a large, bulky brown envelope. “Some items he had with him.” James’s brown leather billfold, cracked at the fold, his playing cards and two small paper bags. Inside the billfold, the library card and a dollar bill. She’ll wait to open the small bags when Nolan isn’t watching.

She inquires about Nicholas. Nolan says he’s in a place called Quarantine. He can’t say when Miranda will see him again.

She asks, “Why did yourself come if you thought James lived alone?”

“It’s my job to doubt what others tell me.”

• • •

Daddy was home. His briefcase met the floor with a soft plunk. A hanger scraped the rod as he hung up his jacket. Linda waited for him to call out in the voice she pictured rising from a deep, black well.

“James Haggerty died yesterday. A heart attack, apparently. I stopped in at Tony’s for a new wiper and he told me.” Daddy often did that when he got home: started talking without checking if anyone was around to listen, spilling his news at once as if he’d forget if he didn’t. His shoes rattled the furnace grate as he crossed into the dining room where Linda stood behind her chair on the waxed wood floor, ravenous as usual, counting the purple fleurs-de-lis on the wallpaper to distract her mind from her stomach.

Steam rose from the green beans Mother carried out from the kitchen. “I didn’t think he was that old,” she said. She always got gussied up before Daddy came home, putting on nylons and makeup, fixing her hair. If Daddy noticed, he never let on. That evening Mother was in a full-skirted baby blue dress with a wide white belt and her usual black heels. When Linda ate at Tereza’s the week before, Mrs. Dobra had been barefoot. Her nipples showed under her scoop-necked blouse and her legs through a thin wrap-around skirt.

“Late forties, according to Tony.” Daddy took his position behind Mother’s chair, ready to hold it out. His white shirt was damp under the arms, his round face flushed from heat.

“Must’ve been the drink, then,” Mother said.

“Did he die in his house?” Linda asked.

“Hello, kiddo!” Daddy said. “I forgot to give you a hug.”

Linda stepped into the brick warmth of his open arms. He smelled of starch and underarms. “Did he die in that big house?” she said into his chest.

“No, on the Pennsy from New York. He’d gone into the city for some reason. Had bags of strange stuff in his pockets, so they say.”

Linda had ridden the fifteen miles into New York City on the train once with Mother and Daddy. She pictured the man she knew only as Crazy Haggerty on a slippery brown seat, his shoulders swaying with the train’s motion. “What kind of strange stuff?”

“I think that’s everything,” Mother said, surveying the table, leaving Linda’s words to hover in the air like dragonflies. Daddy pulled out Mother’s chair. She sat and smoothed the tablecloth, brushing away invisible crumbs. Daddy took his place opposite her and Linda hers between them. They bowed their heads.

Daddy said, “For what we are about to receive we are truly grateful.”

They removed the linen napkins from under their forks. Custom-made pads and a white linen cloth protected the ski-legged cherry wood table Daddy bought Mother last year for their fifteenth anniversary.

At Tereza’s, Mrs. Dobra had taken two pans right off the stove and set them on the bare wooden table without the slightest concern about scorch marks. “Dig in,” she’d said: to canned corn and stewed tomatoes and hot dog pieces, like chopped up worms, swimming in baked beans. Eight-year-old Allen stuck his hand in a huge bowl of potato chips. No one said grace. The table wasn’t quite big enough for five people. Tereza’s stepfather, Jimmy, straddled the chair between Allen and Linda, his thigh pressing against hers. He was slighter than Daddy but the muscles on his arms stood out more. A construction worker, Tereza had said. They moved whenever he ran out of work.

“What kind of strange stuff?” Linda asked again.

Mother put a thin slice of roast chicken, a small mound of mashed potatoes and a spoonful of green beans on Linda’s plate. A canned peach-half waiting in a small dish on the sideboard would be her dessert. Since Linda had inherited her father’s build and was already overweight at a hundred and forty, she’d have to watch what she ate for the rest of her life. She had her mother’s ash blonde hair, which was lucky because the gray would blend in when she got old and be hardly noticeable. Tereza’s black hair was “a regular rat’s nest,” according to Mother who set Linda’s hair in tidy pin curls every Saturday night.

“Apparently he had a child,” Daddy said, unbuttoning his cuffs. “Possibly two.” He rolled up his sleeves. “Tony had quite a bit to say about that.”

“Really.” Linda recognized the look Mother gave Daddy as a warning. When she was younger, they’d spoken in Pig Latin. Eally-ray.

“What did you do today, Linda?” Daddy asked.

“Hung around with Tereza.”

“Interesting expression, that. Can you be more specific?” To Daddy, slang exposed an indolent mind and profanity a dearth of imagination. A single new word in your vocabulary, he claimed, could help you see the world differently. Each month, Linda memorized the words in Reader’s Digest’s “It Pays to Increase Your Word Power.” Daddy might have been impressed if she’d said confabulated, but it wouldn’t have expressed the joy, the shivering bliss, of having a friend who wanted to spend the whole day with you.

“I don’t know. We just talked and stuff.” She didn’t let on she and Tereza had been in eyeshot of Crazy Haggerty’s spooky old house. “How old’s his child? Boy or girl?”

“That’s not open for discussion,” Mother said.

“Why not?”

“Don’t argue with your mother. Did you help around the house?”

“She peeled potatoes and set the table.”

“Good. He had a teenaged daughter and there’s a little boy who might be hers.”

“Roger!”

Dinner at Tereza’s had ended badly, too, after Jimmy asked Linda if she’d ever eaten wild boar and she said no sir, and he said it tasted like polar bear and Tereza made a rude noise and said how would he know and Jimmy asked if Tereza was looking for trouble and Mrs. Dobra rushed in to explain that, after the war, before she and Jimmy met, he had worked in the North. Jimmy said he could tell his own stories. He’d waggled his fork at Tereza and said it was in Thunder Bay, Miss Smartass, that’s in Canada, in case you ain’t learnt that yet, I’m not the dumb fuck you think I am. Nobody spoke after that, just applied themselves to getting the meal over and done with, Linda pretending she hadn’t heard Jimmy’s dearth of imagination.

After dinner, Mother and Daddy sat in the backyard while Linda did the dishes, a chore she rarely objected to because it let her pick at the leftovers. Tonight it also allowed her to eavesdrop through the window over the sink, her ears on full alert to even the rasp of Daddy’s match as he lit his pipe. Their voices were as faint as fly hums, at first, but soon came a buzzing and a hornet-like crossness that was loud enough for Linda to pick out words.

“He should have been shot.”

“No point poking a stick in his dead eye, Betty.”

“Why are you defending him?”

“I’m not. I don’t know enough about it to blame or defend. Neither do you.”

“A teenager with a baby and nobody knew she existed. Isn’t that enough?”

Their voices dropped again and then tapered off. Linda wondered why ‘a teenager with a baby and nobody knew’ meant Crazy Haggerty should have been shot. But Mother said no more. She came in and went up to bed—her modus operandi, as Nancy Drew would have said, when she was peeved. She’d have a headache tomorrow and not come down for breakfast. Linda finished the dishes, thinking about the baffling girl who’d emerged from Crazy Haggerty’s house, the child’s arms around her neck, the sway of her hips as she stepped toward the police car. Something about her had seemed older than teenaged, something that made Linda squirm.

Daddy stayed outside for a while, smoking his pipe. Later, Linda sat on his lap, as she did most nights when they watched TV. His lap never objected to her build.

• • •

“Bill has to clean up some paperwork,” Doris explains as she leads Miranda to a grape-green automobile longer and lower than the police car. “We’ll see him at home later.” She places Miranda’s valise on the back seat. Miranda gets to sit in the front, holding Cian on her lap. His hair smells like Doris.

“I can’t imagine how you must be feeling,” Doris says.

Like a tree drained of its sap. Miranda wants to be in her bed, sleeping this bizarre dream away. Even the air is drowsy.

“If you want to talk, my ears are wide open. I don’t suppose you felt like saying much to those two galoots.” Doris waves at Nolan and Dunn as the cars part ways.

James said every word generates its own force and every action its own unique consequences. She wouldn’t be in Doris’s car if that last morning had gone differently. James built a fire on the stove and set water on to boil as he did each morning. He took the chamber pots out the back door, as usual, Nicholas in his wake. She nursed Cian and bathed him in the sink, mixing cold water from a bucket and hot water from the stove. James returned, kissed Cian’s head and quoted the line from Joyce he always did when he came upon her bathing the lad: Why, when I was a nipper every morning of my life I had a cold bath, winter and summer.

“See how light it still is and already seven,” Doris says, her unborn babe’s chrysalis nudging the steering wheel. “The longest day of the year. We should eat outside.”

Miranda and James would prepare breakfast together, she stirring the porridge, he slicing the bread. They’d eat in silence, James hunched in his chair, concentrating on his food. Conversation came later in the day over tea, after her lessons or following the evening’s “reading from the gospel,” as James jokingly called it, the gospel being the sometimes tragic Ulster Cycle tales or myths of the Tuatha Dé Danann, who arrived in Ireland in dark clouds that blotted out the sun for three days and nights. Sometimes he read in unfamiliar tongues but she liked his voice in any language. It saturated her mind, crowding out her own muddled thoughts.

“What should we make for dinner?” Doris asks, as if she and Miranda do so every day.

“Colcannon,” Miranda says, surprised at her own spontaneity.

“Aha! The accent I couldn’t quite place,” Doris says, glancing over with a smile. “You must be Irish. Bill loves colcannon. Never heard of it before I met him.”

“Sure I’m not as Irish as James.”

“Your father?”

“Aye.”

“I wouldn’t have the nerve to call my father by his first name.”

“He wanted me to. I’m supposing he was not like most fathers.”

Doris’s laugh is a song.

Miranda thinks on her father. Was it only yesterday he said, “Well, then, if I’m to get in a good day’s work, I best be off.” His usual jest. His only work was foraging for their food and other supplies, made easier when the money tree was in bloom. She said, “Strawberries would be lovely if you can manage them.” That’s when he wheeled around sharply and said, “I can’t cover the sun with my finger, can I?” That had to be it: the only thing not as usual, not as always. If she hadn’t asked for strawberries, James would still be alive. The back door would have opened that night and Nicholas would have skidded across the floor to greet him.

Doris turns onto a wide street with a ribbon of trees down its middle. She nods to a building on the right. “Good old Stony River High. Did you go there before the baby?”

“I did not.”

“Private school?”

“Nor that.” How fortunate she was, James said, to be free of the distraction of school and friends. They would only draw her away from her spiritual path. She would advance more under his tutelage because most classrooms moved only as fast as their slowest pupils. And she had too fine a mind to queue up for an education she could easily get from him. Not the true reason, of course. If she were to step foot in a school “they” would take her away from James. But his argument made her envy less the young people she saw from the attic window ambling toward the river she pictured shimmering with faeries and moonlight.

“Did you ever go to school?”

“I did not.”

Doris presses her lips together for a long, silent moment before humming under her breath: a joyless, ominous hum. Miranda wants to say more and, at the same time, nothing. She doesn’t know if she can trust Doris.

Doris rounds another corner. “Has Keen had his shots?”

“And what might those be?”

“Inoculations. Needles to prevent a whole nightmare of things that could kill him: smallpox, whooping cough, diphtheria, tetanus.”

“I think not.”

“Do you have a doctor?”

“We do not.” James kept them well with infusions, poultices, teas and tonics of ginger, yarrow, nettles, mullein, lavender, evening primrose, meadowsweet, lemon balm, bergamot, milk thistle, sage and more. The recipes were in a book handed down from his mother and grandmother, a book he’d added to with his own brews using plants that grew wild in the area and ones he cultivated behind their house.

“He’s got to have his shots, hon. I’ll phone Carolyn’s pediatrician tomorrow.”

Miranda hugs Cian tighter. This brave, new World is a dangerous place.

• • •

At twenty-six, Doris was behind schedule for the six kids she and Bill wanted. It took two years doing it every which way before she’d gotten pregnant with Carolyn. All the while, she’d been working for Children’s Aid, typing up case studies about parents who didn’t deserve the precious babies they’d been given. It broke her heart to come across a neglected child she could have been sheltering. And two were in her car, although Miranda was old enough to be more sister than daughter. If not for the missing side tooth and morbidly pale complexion, she’d have been a looker, with her Teresa Brewer nose and wide-set green eyes. Doris wanted to take a brush to that tangled red-gold hair. The boy was another matter. It had taken all the restraint she could muster not to gasp at his stunted head and narrow, receding forehead.

“Welcome to Nolan Manor,” she said, trying to lighten things up as she pulled into the carport beside the modest red brick ranch house.

The desk sergeant who phoned had said only that Bill needed help with a toddler and a teenager whose father had died. He wanted to put them up for a night or two if that was okay with Doris. Of course it was. Whatever Bill’s job demanded came first. She’d learned that from her Army Wife-with-a-capital-W mother. The sixty-four-thousand-dollar question was who’d fathered Miranda’s baby. While Doris dreaded what she might learn, she was drawn to the mystery as to a locked diary. The whole drive she’d been yakking like an old gossip, trying to loosen the girl’s tongue.

They entered through the side door. Doris set the girl’s suitcase on the faux marble linoleum Bill installed last year for their fifth anniversary. With the boy on her hip, Miranda spun around agog as though she’d never seen a kitchen. She walked her fingers along the turquoise tabletop and matching counters, the paper towel rack above the sink. “What’s this?” she asked, opening the refrigerator without the slightest do-you-mind. She lifted the wall phone receiver, listened and smiled. Flicked the ceiling light switch up and down. Turned on the tap and let perfectly good water escape down the drain.

“Looks like you’re thirsty,” Doris said, slipping a glass under the tap. She filled Carolyn’s Tommie Tippee for Cian and held it up to his mouth. He stuck his tongue in it and lapped. “Adorable,” she said, because he was—like any frail creature needing protection. “We’d better feed him soon. He wolfed down the cookie I gave him at the hospital.”

Miranda pulled out a kitchen chair and unbuttoned the dress that looked like a USO hostess hand-me-down with its shoulder pads and Peter Pan collar. Her small, blue-veined breasts were braless. On the shopping list she kept by the fridge, Doris wrote Bra for M/nursing/other?

“Carolyn stopped nursing at nine months.”

“Sometimes this is all he’ll take,” Miranda said with a challenging lift to her chin.

“Well, sure, if you keep indulging him.” Doris immediately regretted her words. Bill complained she was quick to judge and sometimes he was right. “Will he eat a banana?”

“Sure I don’t know. We never have them. They’re too dear.”

“Let’s give it a go.” Doris held out her arms and Miranda uncoupled Cian from her breast. He whined as Doris lowered Carolyn’s high chair tray over his head. Settled down as she sliced a banana onto it. When he stuffed all the slices into his mouth at once, Doris laughed, nearly missing Miranda slip into the hallway. She lifted Cian from the chair and hurried after her.

“I must relieve myself,” Miranda said. Doris directed her to the bathroom. Miranda asked Doris to go with her and insisted the door stay open. Doris made a mental note to add panties to the shopping list. And more appropriate shoes. She would have liked to throttle someone. After Doris showed her how to flush, Miranda remained, watching the swirling water.

Doris handed Cian to Miranda, desperately needing to pee, herself. When she came out, Miranda was in Doris and Bill’s bedroom, as though no one had taught her manners, studying a Blessed Virgin postcard Doris kept tucked in the frame of her dressing table mirror.

“And who’s this?” Miranda asked softly.

“Mary, our Blessed Mother.” The girl must not have had proper religious instruction.

Miranda stared at a framed photograph of Carolyn on Bill’s shoulders, taken last month at Surprise Lake and, then, like a breeze, deserted the room with Cian on her hip. Doris followed her to the living room. Miranda pushed back the sheers covering the picture window and pressed her face against the glass, leaving marks.

“Would you like to go outside?”

Miranda didn’t reply. Still holding Cian, she plopped herself onto the dark green hide-a-bed and, moments later, bounced up to try one wingback chair and then the other. She stood, picked up a newspaper from the maple coffee table and read: “149 confirmed polio cases among children receiving Salk vaccine. What’s polio, then?”

“You can read!”

“Aye.” She glanced about. “Where are your books?” She turned away, not waiting for an answer. Her hand caressed the wooden console TV. “What is this for?”

“I’ll show you later,” Doris said. “Bring Keen into the kitchen, please. It’s time to cook dinner.” She was done letting this flippy girl call the shots.

• • •

Miranda is bewitched by Doris’s house, especially the kitchen with its white box that keeps food cold and the counters and tabletop the color she imagines the ocean to be, the glittery specks in them like the sparkle of sunlight. Knowing from James that water flowed from other people’s pipes doesn’t make witnessing it any less thrilling. And the long-legged chair! Cian is in it, his hands and mouth happily occupied with tiny animal-shaped biscuits. Doris has given him a clean nappy (she calls it a diaper) and smeared thick white cream on his rash. Doris is so clever, Miranda wonders if she has invented her along with all else that’s happened today.

Doris chops a cabbage she’s taken from the cold box and has Miranda wash her hands before peeling the potatoes. Warm water over her fingers makes Miranda giggle. Doris opens a cabinet filled with pots and pans. What bounty. Miranda and James had only what they needed. Whenever she asked for more of anything, James would say she was indulging in wishful jam-on-your-egg thinking.

“I add onion. Do you?” Doris asks.

“When we have it, aye.”

They boil the potatoes in one pan, the cabbage and onion in another. Miranda marvels at the blue flame Doris can force higher or lower simply by twisting a knob. Living here could be as fine as living with James, perhaps finer. If he were here right now, Miranda would be worrying she hadn’t done her lessons correctly or meditated long enough. She’d be watching his eyes and the set of his mouth for what they might mean to the evening ahead.

Doris mashes the potatoes with butter, seasonings (the true art of the dish, according to James) and real milk from a bottle, not the powdered kind. She mixes it all with the cabbage and onion. “Want a bath while it’s in the oven?” she asks. “I’ll keep an eye on Keen.”

Doris fills the tub with water and bubbles so sweet smelling they make Miranda laugh and cry at once. At home, she had a tub bath once a month after her bleeding ended. The water had to be heated on the stove. Not enough to cover her chest and never, ever, bubbles. Doris brings her a spare nightgown and tells her Bill phoned to say they shouldn’t hold up dinner for him.

Since it has started to rain they eat at the kitchen table, an electric fan blowing on them with the breath of a dozen snow angels. Doris touches her forehead, chest and shoulders with two fingers and mumbles something. Miranda touches her forehead, chest and shoulders and mumbles, “Thank you, Mother, for sending Doris.”

Miranda and Cian will sleep in the small, square unborn babe’s room. Its yellow walls close around Miranda like a hug. “The crib is Carolyn’s old one,” Doris says. So a cot is called a crib. A nappy a diaper. Biscuits: cookies or crackers. Miranda has grown new eyes and ears.

Doris plugs a tiny light bulb into an outlet, pulls the sheet over Miranda’s shoulders and kisses her forehead. Crouching by Cian’s cot, she recites, “Angel of God, my guardian dear, to whom His love commits me here. Ever this day, be at my side, to light and guard, to rule and guide. Amen.” Miranda would have said “Angel of god and goddess,” but that would have spoiled the rhythm of the prayer that has lulled Cian into closing his eyes.

Doris leaves the room and returns with a white plastic figurine: a woman in a hooded robe, no taller than Miranda’s hand. Like the picture from Doris’s mirror, it could easily be Ethleen. “Our Blessed Mother will watch over you tonight and light your dreams,” Doris says, placing the figurine on the dresser near Miranda’s bed. She closes the door.

There’s too much daylight for sleep, even with the curtains pulled. Miranda retrieves the valise from under the bed. With an expectant breath, she withdraws the two parcels James had with him when he died. Only packets of powders and dried plants inside. No strawberries speaking of love and forgiveness. She removes the drawing of Ethleen and the moonstone from the valise. Places the drawing beside the figurine. Taking the translucent stone in her left hand, she whispers, “I am one with the moon” three times. The ritual often yields the sense of a wise and caring presence Miranda associates with her mother. Tonight, it’s Doris.

She tiptoes to Cian’s cot and studies his sleeping face. Now that she’s seen a picture of Doris’s daughter Carolyn, she suspects something is amiss with the lad. James claimed Danú and Dagda brought forth nothing but geniuses. But wouldn’t they give a genius a bigger head?

She returns to the bed and watches shadows skip along the ceiling. It’s her first night here yet she can almost believe this is the life she’s always had. James would be proud she’s forgotten to be afraid and allowed herself to trust. Tomorrow she will be the same and not the same as she is tonight. Tomorrow she will take Cian to a park and ask again about Nicholas.

As the longest day finally darkens, the Blessed Mother begins to glow.

Another scorcher. Waiting for Tereza in the small woods she’d dubbed The Island, Linda closed her eyes and pretended the pines were palms and their cones coconuts. Last year Aunt Libby airmailed a coconut from a real island and Daddy smashed it open with a hammer. Mother said it must be nice to gallivant around the world. A buyer for a department store in Elizabeth, Aunt Libby got to wear Tabu perfume and suits with pleated skirts.

Linda sat on the old hollowed-out log, the ridges scratchy against her bare legs under Bermuda shorts. The log stowed props she and Tereza stashed for Swiss Family Robinson: a bent spoon, acorns, some string, the silver foil from gum wrappers. Tereza saw uses for things Linda considered trash, like cigarette butts. She stripped them and collected the loose tobacco in a Wonder Bread bag. She said they could sell it for food when they escaped from The Island.

Escape to where?

Eyes still closed, Linda was listening to the ebb and flow of cars and trucks on Route 1 four blocks away, pretending it was the sound of the shipwrecking sea, when Tereza snuck up on her like an Indian scout and stomped on her foot. She laughed when Linda yelped. Her hair was wild as if she’d just gotten out of bed. She wore tiny red shorts and her arms were full of cattails.

Linda didn’t like being taken by surprise. “What are those for?” She didn’t care how grouchy she sounded.

“If we let the punks dry out they’ll be better smokes. When they turn to fluff we can make pillows. We can weave the leaves into sleeping mats.”

“The rule is we live on whatever we find on The Island,” Linda said. “Punks don’t grow here. Berries and acorns do.”

“It’s our game, right? We make the rules.”

“It’s my game. I played it a whole year before you came.”

“Yeah, and what have you got to show for it? You didn’t make a tree house. You didn’t make nothin’ we could sell when we get off The Island.”

“What if I don’t want to get off? What if I want to live here forever?”

“Why? Nothin’ to do here, nobody to see. Might as well be Crazy Haggerty’s kid, locked up in that house.” It had been a week since they’d watched the teenager and her baby leave.

“Maybe she liked it there.”

“Not a chance.” Tereza stuffed the cattails in the log and sat next to Linda. “Jimmy said her old man must’ve parked his car in her garage.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

Tereza made a hand gesture Linda could tell was dirty. “I told Jimmy he tries that with me, I’ll kick him in the balls. He backhanded me for that.”

Linda sucked in a breath. You weren’t supposed to say balls. At least she wasn’t. Her cousin’s dog was always licking his. She didn’t like to think of fathers having them. “Maybe Jimmy is wrong,” she said. The way the girl walked out like she wasn’t in any hurry to leave had stuck in Linda’s head. “Maybe Haggerty wasn’t her father.”

“Nope,” Tereza said. “Ma found this.” She pulled a newspaper clipping from under her waistband and began reading aloud as slowly as a third grader, shaping each word with her lips as though tasting it. It made Linda’s jaw ache.

She held out her arm. “Here, let me.” Tereza handed her the clipping.

Linda read, “James Michael Haggerty, 48, of 2 Lexington Street passed away June 21 of natural causes. Predeceased by his wife Eileen. Survived by his daughter Miranda. He will be buried in the potter’s field section of Stony River Cemetery.” Seeing the girl’s name in print gave her a thrill, as though she’d discovered the secret in Nancy Drew’s old clock. “It doesn’t say anything about the child.”

“They don’t want nobody knowing that crazy coot knocked her up. My mom got knocked up with me, you know.”

“Did it hurt?”

Tereza laughed so hard Linda wanted to punch her. She stood and said, “I’m leaving.”

“No wait. Go with me to Crazy Haggerty’s. You gotta see something.”

Linda didn’t want Tereza to call her a chicken again and she itched to learn more about the girl who now had a name. “As long as you don’t tell your folks so they can’t tell mine.”

Not that Mother was likely to seek out the Dobras. At dinner one night she’d said, “Just because she’s the only girl your age this side of the highway doesn’t mean you have to play with her. We don’t know anything about them.” Daddy suggested Mother walk over and welcome them to the neighborhood, poke around in their garbage can. She didn’t, of course.

Tereza pulled a rusty crowbar from the log.

“How’d that get there?” Linda didn’t like the idea of Tereza visiting The Island on her own and putting stuff in the log without her agreement.

“I found it back of my house, hiding in the grass.”

Tereza lived in an apartment building and what she called grass was more like weeds but Linda didn’t correct her.

They crept along the riverbank, approaching Crazy Haggerty’s from the back, stepping around mounds of dog poop. “I never saw him walk that dog,” Linda said.

A small stack of firewood rested against a wall by the back door. “The door’s locked,” Tereza said. “I tried it already. I could’ve busted in but I waited for you.” Padlocked shutters covered the windows on the outside. “I can smash ’em open, easy.”

“If you do, I’m not staying. I won’t tell, but I won’t stay.”

“Look up there.” Tereza pointed to a small window close to the corner of the house, too high to reach without a ladder. Its shutter hung by a hinge. “I broke that one because it’s harder for the cops to spot. I jimmied the window open with a rock.”

“When?”

“Last week, at night. It was too dark to see inside.” She monkeyed up the drainpipe and chinned herself on the window ledge. If Linda tried that, her weight would bring the pipe down. Her heart thumped at the fear of getting caught but she was too curious to leave.

“The kitchen,” Tereza said when she got back down. “Nothing in it except a wood stove. No table, no chairs.”

“They must’ve eaten in the dining room.”

“Or not at all. They could be zombies from outer space.”

Linda sighed in exasperation. Tereza might be older but she wasn’t all that smart. “Zombies are already dead. Crazy Haggerty wouldn’t have died of natural causes if he was a zombie.” Then she noticed two small basement windows barred but not shuttered. Kneeling on a piece of wood so she wouldn’t get her knees dirty, she peered in one window. The light was dim but she could make out two white pillars with black drapes hanging between them.

“I see a cape on a hook,” Tereza called out from the other window.

Linda scooted over to look.

“The guys at the store say Crazy Haggerty worshipped the devil,” Tereza said. “They say he had snake fangs, rat tails and porcupine quills in his pockets when he died. I think the old man kept her as a slave, sicced the dog on her if she didn’t do everything he wanted. Too bad I didn’t move here sooner. I would’ve sprung her.”

“How?”

“I would’ve figured a way.”

“Maybe she was a lunatic Haggerty saved from the horrors of an asylum,” Linda said. “They tie you up and turn hoses on you, you know, attach wires to your head and cook your brain.” She’d learned about asylums from a comic book passed around the school playground. She wanted to believe Haggerty had been protecting Miranda from that or something worse.

Tereza snorted. “The horrors? La-di-dah, Miss Dictionary.”

Linda stomped home alone.

At dinner, she asked, “Did Mr. Haggerty’s daughter have a garage?”

“What an interesting question,” Daddy said.

Linda related what Tereza had said.

Mother looked at her plate.

Daddy said, “You and your mother need to have a chat.”

That night a black bug as big and heavy as Linda climbed onto her back. She couldn’t breathe. She must have screamed because Mother came into her room and rubbed her back. “Hush, angel,” she said. “It was only a dream.”

• • •

Six weeks later Mother disappeared into the hospital for what Daddy called a female thing. “Take care of your father,” she said. “He has no idea what to do with a stove.”

Linda rummaged in her brain for everything she knew about being a wife. Keep your hands out of the wringer washer. Start with the collar when you iron a shirt, then the yoke, then the sleeves. Skim the cream from the milk for his coffee. Be sure all evidence of your housework is out of sight by the time he gets home.

Tereza was no help. She didn’t want to help dust or vacuum or wash floors. “I’m never getting married,” she said. “If I have to clean somebody’s house I’d better get paid for it.” When Linda was stuck at home cooking and cleaning, Tereza hung out with the greasy-haired boys who prowled the neighborhood in a pack.

Sometimes, women from church dropped off a meatloaf, cabbage rolls or even a chocolate cake but you couldn’t count on it. Linda could scramble eggs, dissolve Jell-O and open cans of Daddy’s favorite Manhattan clam chowder soup. She’d sit outside with him after dinner while he talked about his secretary, his boss and the vital role of the cost accountant at Bartz Chemicals. He’d help her with the dishes before their nightly hospital visits. While he was at work, she stood at the sink, guzzling jars of expensive Queen Anne cherries Mother had hidden in the pantry behind a broken toaster and buried the jars later under garbage in the can outside. She sat at Mother’s mahogany dressing table and smeared her face with Pond’s, as cool and creamy as Junket pudding. Licked two fingers as she’d seen Mother do and moistened the tiny brush before dipping it into the little red mascara box. She washed her hair by herself for the first time and needed every bobby pin in the house to set it. Without a mother, how would Miranda know to brush her hair a hundred strokes a night?

Driving with Daddy to the hospital a week after Mother went in, Linda asked, “How come nobody knew Mr. Haggerty had a daughter?” She was in the front where Mother usually sat and got to watch Daddy shift gears. The seat cushion still held Mother’s lemony scent.

“People were scared of him. Your mother went over there once to collect for the Red Cross and he greeted her on the porch with a shotgun.”

“Do you suppose his daughter went to school somewhere?”

“I doubt it.”

Poor Miranda. Linda liked almost everything about school: getting escorted across the highway by a police officer, waiting on the playground for the bell to ring, learning about the solar system, using the pencil sharpener. “Why wouldn’t her father have let her go?”

“No idea.” He reached over and patted her leg. “If only we’d known. Everybody just thought he was eccentric. We left him alone.”

“Where did he work?”

“He didn’t as far as anybody knew. If you asked, he’d tell you he had a ‘condition’ and ‘scraped by’ on his ‘ma’s meager charity.’ I had an inkling he was smarter than he let on. During the war he did his bit patrolling the neighborhood. After that, he kept to himself.” He slowly shook his head. “How long ago that was. To think a little girl was in there all that time.”

He’d never spoken to Linda so confidentially. The regret in his voice emboldened her to confess in a quiet voice, “I used to call him Crazy Haggerty.”

“You weren’t the only one.”

“Daddy?”

“Yes?”

“You said he had strange stuff in his pockets when he died on the train.”

“Did I? Why are you so interested in Mr. Haggerty?”

“I want to know, that’s all.”

“Well, kiddo, there are some things we’re just not meant to know.”

• • •

Linda’s twelfth birthday and Mother was still in the hospital. Daddy said he’d take care of dinner and the three of them would celebrate later that night at the hospital, wouldn’t that be fun? But Daddy didn’t know how to make Baked Alaska. Linda considered trying it on her own but the effort it took on Mother’s part was what she liked best.

“Forget housework,” Daddy said at breakfast. “Spend the day with your little friend.”

Tereza showed up at The Island wearing dungarees that didn’t fit. “Somebody gave ’em to Allen but they ain’t his size.”

“They’re too big in the waist for you.”

“Yeah, and they cut into my crotch. I feel sorry for guys. Ever seen a dick?”

“A what?”

“A penis. A guy’s pee-pee.”

Linda’s face got hot. “I don’t think so.”

“Some are stubby like punks. Others are kinda worm-like.”

“How many have you seen?”

“Well, my brother’s, natch, but that don’t count. Let’s see. . . .” She added on her fingers: “Richie, Vinnie, Paul, Vlad”—the greasy-haired boys who blocked the sidewalk and said “all that meat and no potatoes” whenever Linda tried to walk by.

“They smoke cigs,” Tereza said, “and let me take drags if I kiss ’em.”

Linda was horrified. “Kiss their penises?”

“No, genius, their mouths.”

“Can you taste what they’ve been eating?”

“Natch.”

“How nauseating.” Nauseating was Linda’s favorite new word but Daddy wouldn’t allow her to say it at the dinner table. “Don’t your folks mind you going with them?”

“They don’t ask and I don’t tell.”

Linda didn’t want to hear any more about the greasy-haired boys. She suggested they play Swiss Family Robinson. Tereza said she wasn’t going to pretend anymore until she became a Broadway or Hollywood star. Linda didn’t mention it was her birthday. She didn’t want Tereza to play with her out of pity. She went home and looked up penis in Webster’s Unabridged and then the words in the definition she didn’t understand. Eventually she got to “intercourse” and “impregnate” and began to think about Miranda and Crazy Haggerty.

It made her stomach hurt.