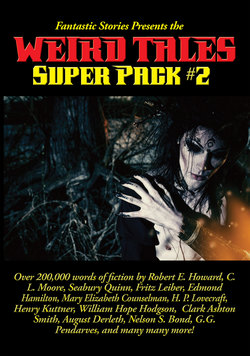

Читать книгу Fantastic Stories Presents the Weird Tales Super Pack #2 - Уильям Хоуп Ходжсон - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Birthmark

Оглавлениеby Seabury Quinn

Last minute shopping at Liberty’s and the Garelies LaFayette had taken more time than I’d reckoned, and the six-seated compartment to which I’d been assigned on the Treves rapide was nearly filled when I finished checking through the provost marshal’s booth at the Gare del’Est and scuttled down the inner platform. Three of the four early arrivals I recognized: Amberson, who as a former New York police lieutenant had been assigned to the Intelligence; Weinberg of the Medical Corps, like me assigned to base hospital work in Treves; and Fontenoy apKern, an infantryman about to take up duties at the provost marshal’s office at the old walled city.

The fourth man was unknown to me and, for no reason I could think of, I disliked him with the sudden spontaniety of a chemical reaction. The double braid on his cuffs marked him as a captain, and where the raccoon collar of his short coat was thrown back, I saw crossed rifles on the neckband of his blouse. His uniform was well-cut and expensive—English-made, I guessed—his blond hair neatly trimmed, his slim, long, white hands sleekly manicured. More of a fop than a soldier he seemed, some dandy from the fashionable East Fifties with a bullet-proof commission going from the secretariat at Paris to staff headquarters at Coblenz; but in the army one goes where he is sent and does the work they set him at.

It wasn’t mere resentment of a grime-and-blood veteran for a pantywaist soldier that stirred my quick, instinctive dislike. It was the smug arrogance of him. Clear-cut as the image on a coin, his profile silhouetted against the window, high-cheeked, hard-eyed, sharp-chinned. Prussian as an oberleutnant of the Elite Guards Corp, that face would have seemed more in its proper setting above the field gray of a German uniform than the olive drab of our army.

The stranger glanced up quickly at my advent, and I had a momentary glimpse of faintly sneering mouth and hard, cold, haughty eyes, then he resumed his reading of the Paris edition of the London Daily Mail.

Greetings were in character: “Hullo,” said Amberson, sweeping me with the quick look of suspicion which is the mark of the professional policeman.

“Thought you’d gone A.W.O.L.,” grinned Weinberg. “Wouldn’t blame you if you had. Lot o’ flu up Treves way; lots o’ work for us poor suckers in the M.C.”

“Hi lug!” apKern saluted me. “Mopped ‘em all up on the Paris sector and goin’ up to croak a few in Germany?”

The blond captain of infantry took no notice of me, nor any of us.

I stumbled over an assorted lot of feet, stowed my duffel in the rack above my seat, and dropped down on the hard cushions. The place across from me was vacant, but a white card indicated it had been reserved. “Wonder who’ll draw it?” apKern wondered. “Pity the poor bloke, havin’ to look at your ugly mug from here to Treves. Gosh, when I came to up at Catigny and saw you starin’ at me, I thought I still was under ether and havin’ a bad dream! If I could a’ talked I’d a’ asked the nurse to slip me a fresh dose of anesthetic—”

“Quiet!” cut in Weinberg. “Who’d know when you were conscious or anesthetized, anyhow? If I’d been there, I would a’ operated on you as they brought you in, you—” His amiable insults stopped half uttered, and a sudden blankness wiped expression from his face as he looked past apKern to the compartment door.

Followed by a railway porter, a girl stood at the entrance. I felt my own heart skip a beat as I looked at her. Mentally I commented, “There ain’t no such animal.”

She was quite young, not more than twenty-three or -four, quite breathtaking in her loveliness. A red cross gleamed upon her overseas cap, and beneath her heavy dark coat with its wide fur collar showed a white stock and the well-cut, smoothly-fitting whipcord uniform of the Red Cross Motor Corps. Three service chevrons on her left cuff showed she was no post-Armistice importation, and her utter lack of self-consciousness showed she was at home with soldiers. More like an effeminate boy than a young woman she seemed as she stepped lissomely between the rows of booted feet and dropped down in the seat across from me. I realized her eyes were golden, a light brown that was almost orange, harmonizing to perfection with her copper hair, her smooth pale cheeks, and slim red lips.

When she took her cap off and shook her hair, I saw that it was close-cropped, almost like a man’s, and riotous with curls.

I cast a glance at apKern, sitting two seats from her, and he must have read the malice in my eyes, for almost instantly he sounded off.

“See this?” he tapped the dispatch case that rested on his knees. “Lot o’ valuable dope in here; list o’ suspected enemy agents and so forth I’m takin’ up to Treves. ‘Captain apKern,’ the general says to me, ‘I’ve got some very confidential documents to go to Germany. They’re so secret that I daren’t trust ‘em to an ordinary courier. Only a man of proved sagacity, indomitable courage, and more than usual cleverness can be entrusted with these papers, Captain. You’re going up to Treves, aren’t you?’

“‘Sure, General,’ I tells him. I’m fed up with all this work in Paris; want to get where there’s a chance for action, so I’m joinin’ the M.P.’s at Treves. I’ll be happy to accommodate you by taking those papers, and you need fear nothing. They’ll be safe with me as if—’”

“‘You published ‘em in the New York Times,’” completed Amberson sarcastically.

I glanced across the narrow aisle at the girl. She was joining in the laugh that followed Amberson’s deflation of apKern. Her lips were opening like a flower, and a smile glowed in her orange eyes. “Lovely!” I whispered to myself. “Perfect—” as I eyed the long sweet line from her waist to knee, from knee to ankle, the small gentle bosom and the long slim hands and feet—“she’s just perfect.”

The guard blew his absurd tin trumpet, and we slid out of the station, past the platform bright with French officers in fur coats or long capes of horizon blue, like birds of brilliant plumage among the somber O.D. of our own and British uniforms, through the blinking lights that marked the station yard and out into the fog-blurred night.

The train had a wagon-restaurant, and presently the girl went forward, followed in a moment by apKern, Weinberg, and Amberson. I’d lunched late at the Café de la Paix and had no wish for food, so settled back in my seat with a copy of the Bystander.

Our coach was German, taken over by the Allies, and a sign phrased with Teutonic arrogance stared at me from the farther wall of the compartment with the information that such indiscretions as smoking or falling from the window were stringently verboten under penalty of heavy fine. I grinned at it. I was an American soldier on my way to conquered territory. Presently their officers would be saluting me as I walked down the street, their civilians crowding to the curb to give me sidewalk-room. Their signs meant nothing to me, and I broke out a packet of Fatimas.

“Smoke?” I proffered the pack to my silent companion.

“No,” he returned shortly, never glancing up from his paper, and with renewed irritation I realized that he had not added “thank you,” to his refusal.

In a little while the diners came back from their meal, on the best possible terms with each other, and I was duly presented to Miss Felicia Watrous of Philadelphia. Moved by common courtesy, I bent to catch the aloof infantryman’s eye, intending to introduce him. For just a moment he looked up at me above his paper, and I was fairly chilled by the cold challenge in his agate stare. To hell with him! All of us, except Amberson who was a major, were his equals in rank. Where did he get off treating us like a lot of railway porters? Let him read his London Daily Mail and be damned to him!

Stories of the front and service, of communications lines, of base hospitals, Paris, Brest, and Saint-Nazarire sped the time till we passed Epernay. The air grew cold with a hard bitterness while the fog congealed to sleety rain that spattered like thrown sand against the window and gushed down the glass like the backwash of a sullen tide. The window casing somehow rattled loose from its sides, and a current of chilled air, with now and then a spit of sleet, came straight against me. After several ineffectual efforts to right matters, I turned the collar of my trench coat up about my ears, slid down until I rested on the extreme end of my spine, and sought forgetfulness of my discomfort in sleep.

Conversation had died down to monosyllables. Even apKern seemed drained dry of wisecracks, and Amberson rose lurching from his seat.

“See you in the morning—I hope,” he rumbled, jerking at the leather cord that worked the single light in the compartment. For a moment the globe glowed with fading incandescence, then we were smothered in Cimmerian darkness.

Was it a trick of tired nerves, the retention of the light-image upon my retina in the dark? I wondered. Somehow, it seemed to me that as night flattened on the window and the blackness closed about us the orange eyes of the girl sitting opposite me glowed with a sort of smoky, sulphurus luminance like those of a cat in the gloom. The impression lasted but a moment. Either she had lowered her lids or my eyes had grown accustomed to the lack of light, and I was staring sightlessly into a shadow as impenetrable as a velvet curtain.

Memory was scratching at my brain, softly but insistently as a cat demanding admission to a room. Miss Waltrous’ face was poignantly familiar to me and, dimly, I connected it with something vaguely unpleasant.

I tried to fit the pieces of the mental picture-puzzle together, assembling keywords, fumbling with my thoughts. The riddle of her strange familiarity—that persistent thought, “I’ve seen her somewhere”—was within reach of my brain if only I could get the facts in proper perspective, I was sure. Her name: Felicia Watrous. Did its syllables strike some note of memory? No. Try again: That face, that sweet, pale oval face, almost too perfect in its symmetry; the long red lips of that red, sensitive mouth; those glowing orange eyes and hair as russet as the leaves of a copper-beech in autumn; she came from Philadelphia—

I had it!

The triumph of remembering brought me up right in my seat, I almost snapped my fingers in delight. Not faintly, but clear-cut as a motion picture flashed upon a screen, I saw that scene in Fairmount Park. I was in my final year of internship and, as always, short of money, had gone to the zoo for the afternoon. Beside the monkey cage a boy and girl stood idly. Through closed lids I could see them perfectly with my mind’s eye, the lad in baggy trousers rolled high above his ankles to display bright socks, a V-necked sweater with the “F” that showed he was an athlete at Friends’ School; the girl in Peter Thompson suit, hatless, her small proud head aflame with copper hair as sweetly poised as a chrysanthemum upon its stalk. They had a bag of sugar cookies and had tossed one to the ravenous little rhesus monkeys swarming up the bars. One of the greedy little simians fastened on a cake fragment with its hand, then, not content, seized another with its hand-like foot, leaped to an overhanging perch and proceeded to feed itself, nibbling first from the bit clutched in its hand, then from the fragment grasped in its prehensile foot.

“Look there!” the lad exclaimed as he nudged his companion. “Lookit that glutton feedin’ his face with hands and feet. Bet you couldn’t do that!”

The innocent remark was devastating in effect. The girl seemed suddenly to lose all strength and wilted brokenly against the railing set before the cages. Her face was twisted in mute agony, her brow was glistening with sweat, her cheeks had gone pale with a pallor that passed white and seemed gray verging on green. And from the tortured mask of stricken features, her eyes seemed to beg for pity.

I ran to offer her my help, but she smiled away my kindly meant assistance. “A—little—faint,” she murmured in a voice that shook as if it took her last remaining ounce of strength to speak. “I’ll—be—all—right.” Then, with the frightened boy assisting me, we got her to the red-wheeled dog-cart waiting by the fountain, and he had driven her away.

That had been in 1910—nine years ago. I had been a barely-noticed bystander—a member of the audience of her brief drama—she had been the star of the short tragedy. No wonder she had failed to recognize in the uniformed medical officer the callow intern who had helped her.

Was there, I asked myself as I leaned back against the hard, uncomfortable cushions of the German railway coach, some connection between the lad’s reference to her inability to feed herself with her foot and her collapse, or had she been seized with a fainting spell? If she had, it sounded like a cardiac affection; yet the girl who slept so peacefully across from me was certainly in the prime of health. More, she must have passed a rigid physical examination before they let her come overseas. Puzzling over it I saw the lights of Chálons station flash past, watched the darkness deepen on the window pane once more, and fell into a chilled, uncomfortable sleep.

*

Consciousness came to me slowly. The window had worked farther down in its casings, and sleet-armed rain was stabbing at my face. My feet and legs felt stiff with a rheumatic stiffness, and my head was aching abominably.

“Damn these Jerry coaches,” I swore spitefully as I rose to force the window back in place. “If I ever see a Pullman car again I’ll—”

My anger protests slipped away from my lips. The blackness of the night had given way to a diluted gray, and by this dim uncertain light I made the forms of my companions out—and there was something horribly wrong with them. ApKern was slumped down in his seat as if he had been a straw man from which the stuffing had been jerked, Amberson lay with feet splayed out across the aisle; Weinberg’s shoulders drooped, and his hands hung down beside his knees and swung as flaccidly as strings with each movement of the train. The girl across from me lay back against her cushions, head bent at an unnatural angle. Thus I called the roll with a quick frightened glance and noted that the stranger was not present.

Yes, he was! He was lying on the floor at apKern’s feet, one arm bent under him, his legs spread out as though he’d tried to rise, felt too tired for it, and decided to drop back. But in the angles of his flaccid legs, their limpness at the hips and knees and ankles, I read the signs no doctor has to see twice. He was dead.

The others? I jerked the leather light-cord, and as the weak bulb blossomed into pale illumination took stock. Dead? No, their color was too bright. Their cheeks were positively flushed—too flushed! I could read it at a glance. Incredibly, I was the only person in that cramped compartment not suffering carbon monoxide poisoning.

I drove my fist through the window, jerked the door open and as the raw air whistled through the compartment, I bent to examine Miss Watrous. Her pulse was very weak but still perceptible. So were Weinberg’s, Amberson’s, and apKern’s. The stranger was past helping, and the air would help revive the others.

My first job was to find the chef de train—the conductor—and report the casualty.

“Find whoever is in charge of this confounded pile o’ junk,” I told an enlisted man I met in the corridor of the next coach. “There’s been an accident back there—four officers and a Red Cross woman gassed—”

“Gassed?” he echoed unbelievingly. “Does the captain mean—”

“The captain means just what he says,” I snapped. “Go get me the conductor toot sweet. Shake it up!”

“Yes, sir.” He saluted and was off like the proverbial shot, returning in a few moments with a young man whose double bars proclaimed him a captain, with the red R denoting he was in the Railroad Section on his shoulder.

It was no time to stand on ceremony. Technically, I suppose, the Medical Corps outranked the Railroad Section, but I tendered him a salute. “Gas?” he echoed as the corporal had when I completed my recital.

“If we haven’t five cases of carbon monoxide poisoning—one of ‘em fatal—back there, I never rode an ambulance,” I answered shortly. “How it happened, I don’t know—”

“How’d you happen not to get it?” he broke in suspiciously.

“I was sitting by the window, and it worked loose in the night. Air blew directly in my face. That accounts for the girl’s not being more affected, too. She was facing backward, so didn’t get the full effect of ventilation, but her case seems the mildest. Major Amberson, who was farthest from the window, seems most seriously affected, but all of them were unconscious.”

We had reached the compartment as I concluded. “Help me with this poor chap,” I directed, bending to take up the dead man’s shoulders. “If they have a spare compartment, we can put him in that.”

“There’s one right down the corridor,” he told me. “Party debarked at Chálons when we took the train over from the Frogs.”

“Thank the Lord for that,” I answered. “If the French were still in charge, we’d have the devil of a time explaining—ah!” Amazement fairly squeezed the exclamation from me.

“What is it, sir?”

“This,” I answered, reaching under apKern’s feet and holding up a metal cylinder. The thing was six or eight inches long by about two inches in diameter, made of brass or copper, like those fire extinguishers carried on trucks and buses in America, and fitted with a nozzle and thumb-screw at one end.

“What’s it smell like?” he demanded, staring at my find uncomprehendingly.

“Like nothing. That’s just it—”

“How d’ye mean—”

“That cylinder was filled with CO—carbon monoxide—which is a colorless and odorless gas almost as deadly as phosgene. It was pumped in under pressure, and late last night someone turned the thumb-screw while we were asleep, let the gas escape, and—”

“Nuts!” he interrupted with a shake of his head. “No one would be such a fool. It’d get him, too—”

“Yes?” I broke in sarcastically. “Think so, do you?” Rolling the dead man over to get a grip beneath his arms I had discovered something he was lying on. A small, compact, but perfect gas mask.

“Well—I’ll be a monkey’s uncle!” he declared as I held my find up. “I sure will. But how’d it happen he was the only one to get it in the neck, when he was all prepared—”

“That’s what we’ll have to find out, or what a board of inquiry will determine,” I replied. “Help me get him into that compartment, then we’ll see about first aid for these—”

“Here, what goes on?” Weinberg sat up suddenly and stared about him like a man emerging from a bad dream. “What’re you guys up to?”

“How d’ye feel?” I countered.

“Terrible, now you mention it. My head is aching like nobody’s business, but”—he bent and touched the supine dead man, then straightened with a groan as he pressed hands against his throbbing temples—“what’s all this? Did his Nibs pass out, or—”

“Clear out,” I assured him. “He’s dead as mutton, and the rest of us came near joining him. Look after ‘em a moment, will you? I’ll be right back.”

*

Fresh air and copious draughts of cognac, followed by black coffee and more brandy, had revived the gas victims when I returned. Amberson was still too weak to stand, apKern complained of dizziness and clouded vision, but Weinberg, tough and wiry as a terrier, seemed none the worse for his close call. Due to her seat beside the window, Miss Watrous seemed less seriously affected than the rest. In half an hour she was ministering to apKern and Amberson, and they were loving it.

“Look here, Carmichael,” Weinberg said as we bent above the dead man while Amberson went through his papers, “this is no case of CO poisoning.”

“If it isn’t, I never used a pulmotor on a would-be suicide in South Philly,” I rejoined. “Why, there’s every indication of—”

“Of your granddad’s Sunday-go-to-meetin’ hat!” he broke in. “Take a look, Professor.”

Obediently, I bent and looked where he was pointing. “Well, I’ll be—” I began, and he grinned at me, wrinkling up his nose and drawing back his lips till almost all his teeth showed at the same time.

“You sure will,” he agreed, “but not until you’ve told me what you make of it.”

“Why, the man was throttled!” I exclaimed.

There was no doubting it. Upon the dead man’s throat were five distinct livid patches, one, some three inches in size, roughly square, the other four extending in broken parallel lines almost completely around the neck.

“What d’ye make of it?” he insisted.

I shook my head. “Possibly the bruise left by some sort of garotte,” I hazarded. “The neck’s broken and the hyoid bone is fractured; dreadful pressure must have been exerted, and with great suddenness. That argues against manual assault. Besides, no human hand is big enough to reach clear round his neck—he must have worn a sixteen collar—and even if it were, there isn’t any thumb mark here.”

He nodded gloomily, almost sullenly. “You said it. Know what it reminds me of?”

“I’ll bite.”

“Something I saw when I was hoppin’ ambulances at Bellevue. Circus was playin’ the Garden, and a roustabout got in a tangle with one of the big apes. It throttled him.”

“So?” I raised my brows. “Where’s the connection?”

“Right here. These livid patches on this feller and the ones on that poor cuss we took down to the morgue are just alike. Charlie Norris had us all down to the mortuary when he performed the autopsy on that circus man and showed us the characteristic marks of an ape’s hand contrasted with a man’s. He was particular to point out how a man grasps something using his thumb as a fulcrum, while the great apes, with the exception of the chimpanzee, make no use of the thumb, but use the fingers only in their grasp. Look here—” he pointed to the large square livid mark—“this would be the bruise left by the heel of the hand, and these—” he indicated the long, circling lines about the dead man’s neck—“would be the finger-marks. That’s just the way the bruises showed on that man at the Bellevue Morgue.”

“Snap out of it!” I almost shook him in my irritation. “Here’s one time when observed phenomena don’t amount to proof. It seemed fantastic enough to find a cylinder of concentrated carbon monoxide in the car, with you chaps and Miss Watrous almost dead of CO poisoning, but to lug in a gorilla or orangutan to throttle our would-be murderer before he had a chance to slip his gas mask on—Poe never thought up anything as wild as that.”