Читать книгу The First Days of Berlin - Ulrich Gutmair - Страница 10

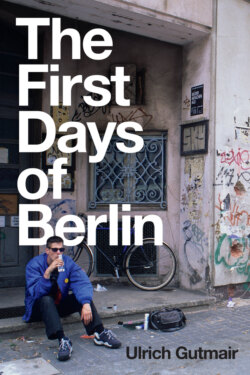

The man who sat by the kiosk outside Tacheles

ОглавлениеKlaus was dead, and the kiosk was gone. Day after day he had watched over the Oranienburger Tor. He would sit there in his lumberjack shirt on his camping chair next to the kiosk, books laid out on the little table behind him, waving to people walking past and engaging them in long conversation. Now, one chill December day in 2005, there was a cardboard sign leaning against the side of the kiosk with his photo and the words Klaus is dead on it. Someone had placed candles and flowers in front of the sign. Alongside them were offerings of bottles of beer and vodka to accompany him on his journey into the realm of the dead.

A little while after Klaus Fahnert died, the kiosk vanished too – it’s visible next to the advertising column on 1950s black-and-white photos – and also the nearby snack stand. The small triangular space on the corner of Linienstrasse and Oranienburger Strasse where Klaus spent his days has been recobbled. It has looked clean and tidy ever since, as if this were a typical West German town grown fat on prosperous decades. Klaus lived in Mitte for fifteen years, for nearly ten of which he was to be found sitting next to Serdar Yildirim’s kiosk, diagonally across the road from Tacheles.

Serdar Yildirim is a small, wiry man with dark shoulder-length hair. It took me a while to track down the former leaseholder of the old kiosk at Oranienburger Tor, though he wasn’t far away. After much enquiring, the friendliest vendor at Dada Falafel told me that the people from the kiosk had moved to the other side of the street. Serdar has set up shop in a repurposed shipping container next to Tacheles and sells articles such as postcards and T-shirts to tourists. He generally works nights. Serdar had known Klaus since late 1996.

‘Klaus was fit as a flea back then’, he says. ‘He walked up, stopped in front of the kiosk and asked for a beer. He told me he was married, had children and loved this part of town. That’s how we met. Then he started coming every day and one day he asked if he could sit next to the kiosk and sell a few books. I said, I don’t mind. If it doesn’t bother the wardens, it doesn’t bother me. He originally came from Bonn and whenever he saw the letters BN on a numberplate, he’d say, “That stands for Berlin Next.” Daytimes aren’t very busy in summer, not many customers, so I’d often sit down with him for a chat’, Serdar says, lighting another cigarette.

By the time Klaus claimed his patch at Oranienburger Tor, Berliners and tourists in the know had long since moved on to other parts of the city to party. Tacheles was just a pesky hangover. The walls of the staircase were sprayed with coat after coat of graffiti, one on top of the other, tags stretching back to the palaeolithic era of the Berlin Republic, the first days and weeks after the fall of the Wall. It stank of beer and urine. Hawkers sold handicrafts on the first floor, and young Italians, Spaniards and Swedes sat in Café Zapata, trying to feel how Berlin must once have felt. For people from the neighbourhood, Klaus was part of the local furniture, whereas for most of the passers-by on their way to the underground station he was presumably just another dosser, lounging around in his camping chair in broad daylight next to a table of books. Klaus was a good fit with Tacheles, which had become one of new Berlin’s international tourist landmarks along with the Television Tower.

Approaching from the east, the party wall of Tacheles is visible from a long way off. It is painted with a large, vague likeness of a woman’s face, and above it is a question: ‘How long is now?’ Is the present a mathematically nonexpansible point in the stream of time that divides the past from the future, or is it more than that? The tourists you see ambling along Oranienburger Strasse have time for now. They wander around taking photos, clearly fascinated by Kunsthaus Tacheles. It’s a bit messy but colourful, slightly dilapidated yet alive. Which is what people all over the world imagine Berlin to be like.

How long is now? It’s a question that sums up handily the spirit of the Wende, the tumultuous years before and after the East German revolution, the sense of a new departure laden with immense possibilities. Now is always. Life is in the present. Tourists intuitively grasp that. However, when they stand gazing at Tacheles and the large piece of empty land around the building, they see more than that. An old wound is being kept open here. Entering East Berlin from the West in 1989, you felt yourself catapulted back into the immediate post-war years; you were moving through an open-air museum. Nothing had been buried, everything lay uncovered. You could engage in archaeology simply by walking around.

Then and for many years afterwards, the wastelands and the scarred house fronts showed that soldiers fought, right here, in the middle of the city. The walls were still pitted with bullet holes from the Battle of Berlin in April 1945. Visitors to Tacheles didn’t need to know that the former shopping arcade and department store were used by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (the Nazi-endorsed German Labour Front, which replaced independent trade unions) and by the SS, or that French prisoners of war toiled away up in the attics. Directly after the fall of the Wall, there was no need for tour guides or information panels to convey the history of Berlin-Mitte. The history of the twentieth century was written into the cityscape – all you had to do was look. ‘Now’ means all the experiences, memories and history present at a given moment in time.

Around noon on 13 February 1990 Leo Kondeyne, Clemens Wallrodt and their friends pull up in an old fire engine outside what remains of the former department store in the Oranienburger Strasse. The squatters climb onto the roof of their vehicle and in through a first-floor window. It is evident from the back of the building that the GDR’s demolition experts carried out their task with great precision. They blew up the majority of the sprawling complex around its central dome because the East German capital’s urban planners wanted to build a street here. The building was still in use in the 1970s. The squatters stand in the large empty space behind the building and stare up into open rooms that have been cut in half.

The complex was built by Franz Ahrens between 1907 and 1909 using reinforced concrete in the modern style. A glassroofed shopping arcade connected the large and still extant entrance arch on Oranienburger Strasse with Friedrichstrasse, and at its central point the arcade opened up into a dome. However, the idea of competing with the major department stores by linking a cluster of specialized shops to a centralized till system, thus making shopping easier, failed after only a year; the arcade-cum-department store closed down in 1914. In 1928 the building was acquired by the electrical company AEG, which renamed it Haus der Technik and exhibited its latest products in the spacious and luxurious showrooms. The first vacuum cleaners in Berlin were supposedly sold here.

In 1933 Nazi organizations began to occupy parts of the building. It was later damaged during Allied bombing raids on the capital of the Third Reich. The bomb damage report for 16 December 1943, filed by Berlin’s anti-air-raid headquarters, indicates that the Haus der Technik was hit during the 160th bombing raid. Two hundred and fifty planes had flown over the city at around 7:30 that evening. The building sustained further bomb damage in 1944.

After the founding of the German Democratic Republic, it was used by the Free German Trade Union Federation and the College of Foreign Trade. The Oranienburger Tor Lichtspiele, a picture house, opened in the building first, followed by the Studio Camera Berlin, the cinema of the state film archive. A branch of the Berlin savings bank and a lingerie shop also moved in. The large cellars were later flooded for structural reasons, and in the early 1980s demolition work commenced.

The squatters occupy the building prior to the first free East German parliamentary elections in March, its scheduled demolition in April and the East Berlin city council assembly elections in May 1990. Construction workers place dynamite into the blast holes by day, and at night the squatters fish it out again. The squatters name the building Tacheles after the free jazz combo of which some of them are members. They are based at Rosenthaler Strasse 68, known as the Eimer because the squatters apparently found buckets in every room. Its full name is I.M. Eimer, meaning literally ‘in the bucket’ or, more idiomatically, ‘shafted’. But I.M. also stands for ‘inoffizieller Mitarbeiter’ (‘informal collaborator’) – someone who was either forced to act as an informant for the Stasi, the East German secret service, or did so out of conviction.

The stand-alone building (there are empty plots on either side) was occupied on 17 January 1990, almost a month before Tacheles, by members of the East German bands Freygang, Ich-Funktion and Die Firma, and their mates. A flyer addressed to the ‘dear people’ of Mitte reads: ‘Since no one seems bothered by the disintegration of many buildings, we, a collective of three rock bands, have taken full responsibility for the house at Rosenthaler Strasse 68.’ They said they were appropriating the building out of ‘euphoria for the present moment’. They would insulate the building for sound and respect the interests of local residents. The squatters proclaimed the house an autonomous cultural centre and established an association called Operative Behavioural Art. Its logo is a giant ear mounted on the roof.

One of the starting points for the occupation of the Eimer was the house at Schönhauser Allee 5. It was home to Autonome Aktion Wydoks, one of whose leaders was Aljoscha Rompe. The stepson of Robert Rompe, the communist resistance fighter, plasma physicist and member of the central committee of the SED (the Socialist Unity Party that ruled East Germany throughout its existence), Aljoscha Rompe founded the GDR’s first official punk band. Feeling B toured the country for years. Concerts in the province were followed by parties, some lasting for days. Feeling B responded to people’s constant griping about scarcities in East Germany with out-and-out hedonism. It wasn’t their political lyrics that irked the authorities but their refusal to toe the line regarding socialism’s world-historical mission; they preferred to party and mess about. The lyrics of one of their tracks, ‘Graf Zahl’ (‘The Count of Numbers’), are a long list of numbers, starting at one and stopping only when the band feels the song has gone on long enough. Two of the members of Feeling B soon moved on to found Rammstein, who once performed at the Eimer before becoming an international synonym for gloomy German pop.

Aljoscha Rompe died in 2000 from an asthma attack in his camper van. An obituary had the following to say about Rompe’s role in the years after the fall of the Wall: ‘He held court at Schönhauser Allee 5 in Prenzlauer Berg, a house that was squatted before the Wende then quickly legalized through tenancy agreements, and came to illustrate in microcosm the Prenzlauer Berg scene’s attempt to conquer the West and its failure to do so. Thanks to Aljoscha, the Schönhauser Allee house became a hub for East Berlin left-wingers, with concerts in the courtyard, its own pirate radio station up in the attic, a cinema in the cellar and lots of drinking in makeshift bars with a shabby living-room charm. These good-time guerilleros had the cheek to tap into public funds and build a recording studio, and Autonome Aktion Wydoks fell only a few votes short of winning seats on the district council.’

Autonome Aktion Wydoks received 824 votes in the East Berlin local elections. The monthly membership fee was five marks, and the statutes said that anyone ‘not too flabby or floppy and able to withstand a constant barrage of at least 150 phons of music at our bar’ could join, according to the German news magazine Der Spiegel. Immediately after the Wende, while it was still a loose association of East German punks and not yet a party, the Aktion called for people to grab empty houses in East Berlin first before others got there.

The flyer announcing the occupation of the Eimer in Rosenthaler Strasse concluded with the words ‘From Wednesday, Berlin will be a cultural metropolis. People of the world, hear the signal!’ It was meant as a joke, but it was still accurate. The squatters chose buildings in strategic spots. One of the heartlands of this future cultural metropolis was in the old Spandauer Vorstadt, a former suburb between Tacheles and the Eimer diagonally bisected by two parallel streets – the neighbourhood’s main thoroughfare, Auguststrasse, and Linienstrasse. The Scheunenviertel (Barn Quarter), part of the Spandauer Vorstadt, and the Rosenthaler Vorstadt north of Torstrasse were also part of the new district of Mitte. Many artists were attracted to live and work there because there was ample room for ateliers and temporary art projects that either cost nothing, being squats, or were cheap by virtue of being available on temporary licence.

The streets of Spandauer Vorstadt had always been home to upstanding citizens alongside nightclubs and brothels. Leo Heller wrote of Linienstrasse in 1928 that it was ‘the main artery of a neighbourhood traditionally associated with crooks’. But it wouldn’t be right to call these roads mean streets, he noted, because ‘strangely, the nastiest and most notorious areas of Berlin are also home to an honest, solidly middle-class population’. Heller mentioned Linienstrasse being the territory of ‘adventurous ladies and their protectors’. The road was lined with hotels, student bars and dives such as Zur Melone, frequented exclusively by burglars. In the late nineteenth century, the Eimer building in Rosenthaler Strasse housed a popular bar called Der Blaue Panther with an adjacent brothel. Prostitution returned to Oranienburger Strasse the summer before the fall of the Wall: the whores were a few months ahead of the revolution. The galleries, bars and clubs that appeared in the neighbourhood soon afterwards foreshadowed its future as a desirable and expensive part of the city.

Fig. 4 Wrecked car in Auguststrasse, 1990

Mitte’s importance as a location for galleries dated back to the days of East Germany. Friedrich Loock started his first gallery in early 1989 in his small flat in Tucholskystrasse before later moving Wohnmaschine to shop premises in the same building. Legend has it that it was he who came up with the idea in the winter of 1989 of organizing an exhibition in the old shopping arcade in Oranienburger Strasse that was squatted and named Tacheles soon afterwards. When the Wall came down, Kunst-Werke opened its doors in Auguststrasse. Judy Lybke’s gallery Eigen + Art took up residence a few buildings away, allgirls gallery was diagonally opposite and for a while Galerie Neu ran a few rooms at the other end of the street. A sculptor opened Hackbarths in Auguststrasse, a corner pub that is still there today. And so, after the fall of the Wall, a web of galleries, bars and clubs quickly came into existence. Art was also the ongoing result of productive hang-outs in bars run and frequented by artists, places where they could share ideas with colleagues, critics and gallery owners.

There was certainly no shortage of opportunities for such conversations at the counters of bars and on the edge of the dance floors in Mitte. Dozens of bars and small clubs sprang up in the area bounded by Chausseestrasse in the west and Alexanderplatz in the east, Oranienburger Strasse and Invalidenstrasse in the south and north. Clustered around Hackescher Markt were Aktionsgalerie, Assel, C-base, Eschloraque Rümschrümpp, the berlin-tokyo gallery, the Gogo Bar, Sniper and Toaster, and in Rosenthaler Strasse you could find Club for Chunk, Delicious Doughnuts and the Eimer; there was Sexiland and the Imbiss International snack stand on Rosenthaler Platz, and the Boudoir, the Glowing Pickle, Hohe Tatra and Subversiv in Brunnenstrasse; Ackerstrasse had Schokoladen, and then there was Acud in Veteranenstrasse, and Suicide Circus in Dircksenstrasse. Mutzek in Invalidenstrasse subsequently became the Panasonic. There was a whole array of Monday bars. For a while 103 took up residence near Oranienburger Strasse, as did the fourth and fifth iterations of WMF, which had been hopping around the city since 1990. People went to Kunst + Technik on the banks of the river Spree opposite the Museumsinsel.

This is only a selection of local clubs. Some stuck around for long enough to become fixtures, some existed for a single summer or winter and others for just one party; very few have survived to this day. Some places quickly made the listings in the city’s magazines, others you could only find if you knew the right people or happened to be in the right place at the right time. Flyers publicized parties and exhibition previews. Sometimes music and loud voices would lure you into a courtyard as you were walking past, and you would stand there outside a house, in a courtyard, by a door, listening out for where the party was. The best plan for someone unfamiliar with the neighbourhood was to get out of the underground at Oranienburger Tor and start their tour at Café Zapata or Obst & Gemüse.

Serdar’s cousin was the first Yildirim here. He opened his snack stand in April 1993. The small building used to be a public toilet in East Germany, perhaps even in Hitler’s day. Now Serdar’s cousin supplied the locals and the Tacheles squatters on the other side of the road with doner kebabs, boreks, multivitamin juice and beer until four or five in the morning.

Serdar’s family soon took over the kiosk next door. Magazines and newspapers were spread on the wide shelves in front of the glass-fronted stall, and tobacco and drinks passed out through the large window. Serdar was fourteen when he started to lend his parents a hand. When he first took his place at the news stand, Café Zapata had opened at Tacheles diagonally opposite, Obst & Gemüse a little further on. People used to drop peanut shells on the floor there, and by the early hours a layer an inch deep would have formed. They drank beer from the bottle standing up, as had long become the custom in Kreuzberg and Schöneberg. In the summer, squatters from Mitte would sit at the tables and on the pavement alongside guests from all over the world. Obst & Gemüse and Café Zapata were there before any other pubs had really got going in Mitte.

‘The Zapata and Obst & Gemüse were enough at the time. The street was busier then than it is now’, Serdar says. ‘People lived in Tacheles and in the building next door. The whole thing was all open, and anyone could just go in and out. There were hundreds of people, from England, Ireland, Spain, Italy, West Germany and East.’

Many others were also involved in German reunification. Serdar’s list could be a lot longer. Totting up the nationalities, he left out the young Americans, Austrians, Australians, Yugoslavs, Poles, Russians, Lithuanians, Finns, Dutch and other overwhelmingly young visitors for whom Tacheles was a gateway into a different land after the fall of the Wall. This was a place where sometime sightseers became squatters, passers-by became partakers, rovers evolved into ravers and middle-class kids got creative. Tacheles was the interface between the official city and the uncharted territory of Berlin-Mitte with its squats, temporary studios and bars, improvised living-room galleries and nomadic basement clubs.

The reunification of West Berlin and the former East German capital was sealed on the dance floor and in bars, at previews and in beds in occupied houses. Everyone in Mitte came from somewhere, which was equally true of the people who’d gone nowhere. The citizens of the capital of the GDR stayed in the same place. They shut the door behind them one evening, went to sleep and woke up the next morning in a different city. The people who drove out the Politburo in the autumn of 1989 and occupied the Stasi’s Normannenstrasse headquarters during the winter were desperate to see the world beyond the Wall, but within months the whole world had come to them. The streets of Mitte echoed to the sound of English, Spanish, Italian and Russian. Given that a majority of East Germans couldn’t speak any English, most of the foreign pioneers quickly picked up a smattering of German to be able to chat, shop and order food at a snack bar.

In his 1992 documentary film Aufgestanden in Ruinen [Risen in Ruins], Klaus Tuschen presents the early days of Art House Tacheles. He shows how an open commune develops into a cultural venue, how a social structure morphs into a subsidized institution. We watch people arguing in plenary sessions and the house’s spokesman taking government minister Rita Süssmuth on a guided tour, describing the various cultural activities in his audibly Swabian accent and informing her about the ongoing repairs. The minister is in a good mood and obviously enthused. Less impressed by the in-house developments are a group of East German punks, including a child, who feel bullied. The professionalization and institutionalization of the house are good for the artists and theatre professionals who plan to work here. The punks, who just want to live and party in the building, are already in the way. In the middle of this laboratory – a microcosm of the way Mitte is heading – a construction squad of young Brits, Australians and Americans is on the job. They sit in front of the camera in their sturdy boots and dusty clothes and explain how they want to remove all the rubble from Tacheles’ cellar so that it can host one of the first clubs in Mitte: Ständige Vertretung.

‘We couldn’t do this in London or any of the other cities we come from. That’s why this is happening in Berlin’, a reddish-haired Brit says.

His American mate says, ‘None of what we’re doing here is forever. Whatever you do in life, it’s only ever temporary.’ But Tacheles is more than a squat. ‘It’s a monument to the East German squatter movement.’

The Tacheles squatters bought cigarettes from Serdar Yildirim, and he made friends with some of them. From time to time, he would have a beer at Café Zapata after work.

‘Once, when I was taking a taxi home at four in the morning, I saw Klaus outside the shop. He’d set up his stall and was just sitting there. The weather made no difference to him. I had an awning and so if it rained, he’d move his stand over to the side of the shop where he wouldn’t get wet.’

Serdar says that Klaus Fahnert used to sleep in an empty plot just around the corner in Torstrasse.

‘That’s where he used to store his books. He would comb skips for books and old lamps. He didn’t really sell them. He gave a lot of things away. Many people donated a few marks or bought him a beer. Begging wasn’t his style. He was very popular in the street, and all the kids knew him. He often ate at the snack stand, and lots of people, not just people from the bakery or the pizzeria on the corner, used to give him food. Almost every day, the nice waitress from the German pub opposite would bring him something to eat, with sauerkraut and potatoes, all wrapped up. Klaus talked to people, and lots of people liked talking to him. He was no idiot. He was pretty smart actually. He’d talk politics. His nickname was “Mr Mayor”. Joschka Fischer often came here to buy something in his funny hat.’

Joschka Fischer, the former agitator of a fairly unsuccessful attempt to organize workers at the Opel car factory in Rüsselsheim, a militant member of the Revolutionärer Kampf group in Frankfurt, taxi driver, translator and actor, was vice chancellor and foreign minister of the Federal Republic of Germany when he stopped off for something at Serdar’s kiosk in the early 2000s. He lived in Tucholskystrasse. His building was three minutes by foot heading down Oranienburger Strasse from the kiosk towards the synagogue.

‘He knew Klaus and would always chat to him for quite a while. That’s why I like Joschka Fischer – he didn’t look down his nose at people’, Serdar says. ‘He always had a look at the books Klaus had and would often buy something. Whether he read them is another matter.’

Klaus Fahnert liked wearing badges on his lumberjack shirts. A TV reporter was struck by one saying ‘Stop Stoiber’ two days before the federal elections in September 2002 when Edmund Stoiber, the head of the Bavarian Christian Social Union party, was trying to dislodge the incumbent red–green government led by Gerhard Schröder and Joschka Fischer. Since Klaus was supposed to represent the homeless people of Mitte in her report and was displaying political messages, the journalist asked if he voted. To which Klaus’s answer was: ‘Your princes are rogues and layabouts. I would abhor voting for you.’ These are the only words ever spoken by Klaus Fahnert that show up on the internet.

There’s a photo of Klaus hanging right next to the door of Serdar’s new kiosk.

‘Klaus was actually quite happy with his life’, Serdar says. ‘But you know how it ended?’