Читать книгу The Foreign German - Umeswaran Arunagirinathan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

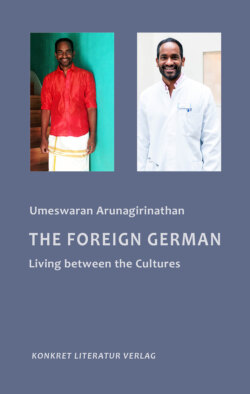

THE FOREIGN GERMAN

ОглавлениеWE WERE FOUR CANDIDATES. One even came with suit and tie, although the day before we had, at his suggestion, decided to appear quite informal at the examination. Only in shirt and pants. A kind of egoistic personality disorder, I thought. We were all very nervous. The last written exam, the so-called hammer exam, we had already successfully passed. Now only the results of this oral exam separate us from being a doctor.

After about 30 minutes of fearful waiting, the examiners called us in. We had all passed! The fellow student in a suit had even received a One. (A). Outside, waited my friends and student colleagues: Freddy, the Fredericks family. Isabel and Madlen with their children, who all called me Uncle Umes. They brought a special non-alcoholic sparkling wine for me. The parents had come for the other candidates, for me my friends were my family. Of course it would have been marvelous if my parents had been there to share the fulfillment of the dream of my life – becoming a doctor. I took my Nokia cell phone with its little antenna out of my pocket and called my parents in Sri Lanka. My father answered.

“Dad, it’s me, Umes. I passed my exam, now I’m a doctor.” I felt my father’s joy on the phone, he said: “You have managed to become a doctor, despite so many difficulties. We are all so proud of you.” I was the happiest I had ever been. It was the first time my father said he was proud of me. Unfortunately I had to end the call quickly as a telephone call to Sri Lanka was then rather expensive.

I didn’t have much time to celebrate or relax. In a week’s time already, I was to to take up a position as assistant physician at the University heart center in Hamburg-Eppendorf. I was happy and thankful that I had gotten this position. Ever since I had worked as a temporary assistant in the heart surgery in Luebeck during my studies, I had been fascinated by heart surgery.

As a non-German, at first I was not given certification, but rather “a permit to engage in medical practice.”

I remember well that day that I got the call from the secretary of Professor Reichenspurner at the University heart center. I was sitting already in bus number 9, on my way home from the University Library. She informed me that I was invited to a personal interview and described the way to the heart surgery in East House 70 on the site or the University Clinic in Eppendorf.

I was very excited and worried about what I should wear. My only suit that I had bought for 20 Euros from a second-hand shop for a Un iball, seemed inappropriate for the introductory interview, but I had no money for a new suit. My colleague Alexia, with whom I had studied everyday the last months before the exam, was able to help. She asked her boyfriend to lend me one of his. He agreed. As I already had suitable shoes and a shirt, all that was missing was a tie. Alexia always knew how to dress well, and she also knew how men should dress. We went shopping together and bought a blue tie with grey-white stripes. Very serious, matching well her boyfriend’s suit. It was fabulous, wearing a Hugo-Boss suit. I felt good in it. On the day of the interview I took the regional express from Luebeck to Hamburg. It only cost me 5 Euros, as I was able to travel with a group ticket.

At the main station my best friend Sahar waited for me. She is Iranian, and I am kind of a big brother for her. As there was still a little time before the interview, we went into a cafe on Siemersplatz not far from the University clinics. I had a black tea with milk and sugar, the way I liked it when I was a child. From the café I could see the Restaurant Antikes, where I had a weekend job as a dishwasher during my abitur time and the first semester in Luebeck. And now, 8 years later, I was going to apply for a position in further education as an assistant in heart surgery. What a trip!

Sahar left me at the side entrance to the University clinics. With the secretary’s directions I quickly found East House 70. Tense, I waited for the interview to begin. It all went very well. At the end I could ask questions or say something.

“One day I will be a heart surgeon, I would be very happy if you would be my professor,” I said to Professor Reichenspurner and said goodbye to him and the other head physicians who attended the interview. Except for a gray-haired doctor who gave me a skeptical look, all of them shook my hand. On this day I couldn’t imagine that this head physician would one day become a good adviser to me..

The daily work of an assistant doctor doesn’t match the picture of it I had made myself during my studies. Yet there are clear guidelines from the medical board for the training of a heart surgeon, regarding duration and content. But there is no regulation for the training of young doctors, and there is no guarantee that an assistant doctor can become a specialist within a given time frame. The training at a medical specialist is supposed to take six years. Actually the average length of time for the training as a heart surgeon in Germany is more than nine years.

Thousands of young assistants work day and night without the observing of the European labor protection laws and without pay for hundreds of hours of overtime. They do it in the hope that those responsible will, in the long run, train them well. These assistants in our country feel like a squeezed lemon after their hospital work. It is very difficult to motivate doctors to work publicly for their own betterment. Already during their studies, the interest in academic politics in negligible among medical students. On average, their voting participation for student body officers lay just under 15 percent. We fought on election days, even with hotdogs and beer, for every vote cast to get voter participation up over 20 percent. Unfortunately, unsuccessfully.

Just as difficult was it to get the participation of a doctor in the worker council of the hospital. A hard fought battle. Most doctors were not interested in the rights of the employees, and the assistant doctors do not run because they’re afraid their council work will be a disadvantage for their training.

In almost all professions, there are training contracts that give the trainees the security that they will have the appropriate qualifications. In medicine, the clinic director alone decides whether and when an assistant will be trained as a specialist. Regulation of the training by a medical board or by politics does not happen in Germany, despite numerous objectively based shortcomings and numerous complaints.

I didn’t want to criticize this system, without myself contributing toward improvement. Therefore I offered to be assistant speaker in my clinic and ran for the management council as the sole doctor among more than 200 medical co-workers.

In the first years of my training I was assigned as doctor to a station that took over patients who after a surgical heart intervention stayed there until their discharge. It was station H5B, my home at work. Every day I pushed the visitation cart with the patients’ electronic files from one room to the next, going from patient to patient. Most of the information about a patient’s healing process I got from the proper caregivers. That is the professional group in a hospital that spends the most time with the patients.

I stood before room 513, the assigned caregiver spoke hesitantly to me: perhaps it would be better if a colleague could take the visit. It was visibly unpleasant for her. I didn’t kwhat to think about it, and wanted to know what was going on. She came right out and said the patient, Mister Clausen, had complained about being treated by a black man, who wasn’t even a regular doctor at the clinic. The patient’s wife also had called the station and asked if a black man worked in the clinic as a doctor. That surprised me very much, for during my visit the previous day I had not noticed anything peculiar in Mister Clausen’s behavior. As usual I had entered the ward with the greeting ”Moin Moin, dear friends” and had asked every patient how he was feeling. When I asked Mister Clausen, he just looked out the window and said nothing. I had assumed that the 80-year old patient had gone through a difficult bypass operation, and was not yet able to respond to my question.

That his behavior was directed against me, hurt me, but I said to my caregiver colleague, “It doesn’t matter whether he is a Nazi or a criminal or whatever prejudices he may have, he is my patient and I will continue to treat him.”

The wife’s complaint circulated quickly in the clinic. My medical superintendent became angry, and told him he could be transferred anytime to another clinic. I insisted that he was my patient and that I would like to continue to treat him, unless he chose to leave the clinic voluntarily.

I recalled a similar situation when I had looked over a patient during my night shift, who had to be treated with many medications because of a weak heart. I wanted to be sure that his condition was stable, that I did not have to take further measures.

The next day the patient complained about the visit of a station doctor who was a pakistani refugee who had come into the room at night and had said he was a doctor. My colleague became angry about this patient and told the superintendent about it. The superintendent said to the patient during his visit quite casually: “Please don’t be surprised that there are pakistani refugees working in this clinic. They are, by the way, the best we have.” and left the ward. My colleague who had been there at the time told me the story, and we enjoyed a good laugh about it.

Now I had the second visit with Mister Clausen, who didn’t want to be treated by a dark skinned doctor. For me it was important to get along with him, detached and polite, without emotion. I had to treat every patient equally well, irrespective of background, skin color, religion or political persuasion. This is my medical duty. Even a Sri Lankan president, responsible for the persecution and annihilation of thousands of Tamils. If he is my patient, I have to treat him as I would my own father.

I entered room 513, greeted Mister Clausen, listened to the noise from his lungs, checked the wounds on his breastbone and the right thigh, where the veins had been taken for bypass material, and thoroughly inspected his legs for edema. I explained to him how important the regular breathing exercises were after heart surgery, and that during the day it would be better for him to sit, to stand, or to walk rather rather than lie in bed to prevent his getting pneumonia. Pneumonia, in older people, can even end in death. I asked him to activate the muscles of his legs, when sitting, with foot movement, so that the muscle pump could force the peripheral edema quickly to the heart and thus over the kidneys. Lastly I formed a small ball from OP socks that he should use for hand gymnastics in order to get rid of the hand edema.

Then with the nurse I prepared the removal of the thorax drainage that had been laid for the discharge of wound fluid. For the patient, the pulling out of the drainage was very unpleasant. I patiently explained to Mister Clausen every step and removed the drainage without problem. I also explained to him every medicine that he had to take right away. I visited him daily and I didn’t hear him utter a word. Mostly he avoided looking at me. That was frustrating.

Mister Clausen made progress, and there wasn’t ever any rhythm interruption, as is often the case with a heart operation caused by electrolytic loss or volume shift. I removed his pacemaker cable which had been inserted during the operation. This too I explained precisely.

Normally the ultrasound scrutiny was conducted by colleagues of the late service before discharge. Because it was important for me, and also because I considered it a challenge to give Mister Clausen the opportunity to get to know me, I carried out the scrutiny myself, colors explained the black and white pictures and the structures of the heart and the colors in the color Doppler over his cardiac values.

I also worked on locating a rehab clinic for him, in order to fulfill his wish for a stay in the Curschmann Clinic on the Baltic, and telephoned with the women of the rehab management. On the seventh day after his bypass operation I planned to allow him to be transferred to a rehab clinic. On the day of the discharge, I went to room 513. Mister Clausen was sitting on the edge of the bed, his packed bag sat on the chair and his cane leaned on the foot of the bed. I was happy that he had got through the bypass operation without complication. I wished him well and said: “Keep away from hospitals, keep well, I would never like to see you with us again.” I smiled and left the room to continue my visits.

Prejudice and rejection, of course, I find not only at work in the clinic, but also in daily life and in my leisure time. Often I have not been allowed into discotheques because of my dark skin. They tell me that I could become aggressive and eventually cause trouble. Already during my Abitur time and particularly during my study years in Luebeck I had problems getting into a discotheque. Sometimes it was: “Sorry, today no foreigners can come in, because last week ten Turks caused difficulties.” What did I have to do with the behavior of these ten Turks? What do foreigners or Turks living among us have to do with ten violent youth?

If I will always be considered only a foreigner by others, I can’t ever in my lifetime become a part of German society. And just as small a chance if I see myself only as a Sri Lankan. For a long time, I have felt myself a German citizen and a part of this society -- until a racist idiot wants to rub out this feeling again.

Like on an evening at the Rosenheim fall festival. My residence mate and friend Berndi comes from Rosenheim, a town south of Munich, with a marvelous view of the Bavarian alps. He enthusiastically showed me photos of the Rosenheim festival. Men wearing Lederhosen and colorful costume shirts and vests, and women in gorgeous dirndls. The colors remind me of a traditional Tamil wedding with all the colorful Saris and shirts. My curiosity was aroused and I wanted to experience a festival in Rosenheim, even if I didn’t drink beer. Berndi smilingly reassured me that there would be plenty of apple "spritz" for me.

I booked a flight from Hamburg to Munich in good time and waited there for the regional express train in the direction of Salzburg. After about an hour I arrived in Rosenheim. Berndi with his girlfriend Heike and my hostess Birgit, a friend of theirs, picked me up at the station. With Berndi’s colleague Frank from Hamburg, we drove to a big costume shop to get me a pair of Lederhosen. There was a huge selection at every price. With Brigit and Heike’s approval I got my first Lederhosen for a proud 385 Euros. Many pay over a thousand euros for a Lederhosen.

We bought a suitable vest and a shirt, shoes I had already acquired in Hamburg, and the matching knee stockings I had been given by Heike and Berndi in March on my birthday as invitation to the festival.

Brendi drove me around the Rosenheim area and I marveled at the glorious countryside at Chiemsee (a large lake) with the mountains in the background, a dream. Then we drove to the village of Zacking where I enjoyed the hospitality of Berndi’s parents.

Berndi’s father showed me his garden, with its herbs and fruit trees and especially a small vineyard behind the house. We sat in the garden and drank homemade apple juice. The garden reminded me of the many banana plants and mango trees in my parents’ backyard, but the vineyard was very special.

The next day we all went together, in full costume, to the fall festival. A very unusual feeling, to be in Lederhosen, Bavarian and traditional. I had imagined it would be uncomfortable, but the Lederhosen sat well and looked good on me. Berndi had wisely reserved a table for us in a huge tent with 5000 seats. The waitresses were able to carry an unbelievable number of beer mugs at one time. In the middle of the tent there was a stage, where music was played and sung. The later the evening grew, more and more people stood on the benches, sang, danced, and drank beer. I didn’t understand the songs that were sung, but the mood was happy and relaxed.

While my friends drank beer, I ordered an apple shorle and half a chicken. It is customary to eat chicken with one’s fingers. I was accustomed to this; until I was twelve, I had only eaten using my fingers.

In front of the tent there was a fair, like at the Hamburg cathedral. Many families were in crowds with their children, even the littlest of the little also wore a costume. I was happy to be at this happy festival. Again and again I got a new table neighbour as soon as there was a free seat. One says hello with “Servus” and clinks with the beer mug, and quickly a stranger becomes a friend with whom one celebrates and laughs.

After the fall festival we went to the Rosenheim Asia snack shop, which for Heike was a tradition, where there were asian dishes offered at reasonable prices. We stood with our Asian chicken food along the street and watched the inebriated flock on their way home. Some were hardly able to walk forward, others were singing enthusiastically and dancing in the street. After we had eaten, I went with the Rosenheim clique – Heike, Berndi, Birget, Christian and Maria – to a discotheque. Everyone got in the door without trouble, but I was refused entry. Like so often in my student days in Luebeck. Back then I had learned not to get involved in a discussion with doormen. But it was devastating to be treated again this way after such a beautiful day.

My friends didn’t want to accept this treatment and argued with the doorman. His arguments were, if one wants to call them such, his prejudices, absurd and not acceptable.

For my friends it was unpleasant that their guest could not be admitted to the discotheque where they had celebrated for many years. Whether I had gotten in if I had shown my German ID, I rather doubt. Sooner or later we hope such people will accept a German citizen who must not be light skinned, blond, and blue-eyed, but that a German citizen could look like me. And I hope they will learn to treat foreigners and Germans equally. This seems to be a long time away.

I convinced my friends to move on. Then we stood before another club, where I couldn’t be admitted either. At this moment I actually had to laugh – I said thanks and turned away and left. My friends were ashamed of what had happened and I felt bad because I had caused them an unpleasant experience.

Hardly fifty meters from the disco lay an unconscious individual on the ground, while the police tried in vain to shake him awake. I went over and offered medical assistance and checked the young man’s circulation: a strong pulse with sufficient blood pressure, pupils reaction to light, normal breathing. A typical condition of full drunkenness. I brought the young man into a stable lying position and asked the police to take him to the hospital for observation, and continued on with my friends.

We stood in front of the third disco, and my friends went first to the doorman and asked whether he would admit their friend from Hamburg. He had no objection so we went in and partied away our frustration.

On the way home I encountered a big blond youth pointing with his index finger and saying to his buddy, “Look at that, we have a nigger in town.” Perhaps I should come to Rosenheim more often, maybe many more dark-skinned people like myself should go to the fall festival in Lederhosen. Maybe then the young man would say one day, “Look at that! Umes is in town.” That would be beautiful. There’s scarcely another country in the world that has better medical coverage than Germany. If we intended to keep this medical standard in our health system, we have to be prepared to make people from other countries our fellow citizens.

Patients will get older and older and even more people will need assistance. The need for care personnel is growing so fast that we can’t even cover the need in several of the federal states. For many Germans the care profession is not attractive, many re-train, change their profession or emigrate to other countries where there are better financial incentives.

We are dependent on the people who come to us from foreign countries, for they accept the salaries and are ready to make contributions to our health care system. This, however, assumes the recognition of and respect for our foreign colleagues. I am glad and thankful that until now I’ve not had to hear discriminating phrases in my clinic like: “Look at that, here comes a nigger with a smock,” or remarks like that of a colleague who was traveling with his family in Africa, and joyfully reported that on an “all inclusive vacation” a negro had been provided them!

While I was standing in front of the patient room 527 with the visitation cart and was studying the next electronic file, suddenly Mr. Clausen, who was waiting for transport to rehab clinic, tapped my shoulder. When I turned around, he said: “You’re a good boy,” giving me a friendly look. That was one of my most beautiful experiences at the hospital. Man is able, until his last breath, to learn something new. It would have been unreasonable to shove Mr. Clausen in a drawer with the label “racist.” It would also have been understandable if I had not continued to treat him. The reasonable reaction was just what I had done – going toward someone who distances himself from you because of prejudice.

Presumably Mister Clausen had never before had the opportunity to get to know a dark-skinned man. Perhaps, in the future, he’ll encounter a colored person differently than before. Perhaps, with my behavior, I had given an 80-year old man the possibility that he wouldn’t die a racist. I think it’s important to engage in dialogue with those who think differently, even if it takes energy and patience. If we didn’t invest in these qualities, we won’t change anyone. With our help they can have the possibility of leaping out from their own shadow to see every person as a human being and not to be make distinct ones. The foreigner remains foreign so long as he feels himself foreign and is acknowledged as foreign by society.