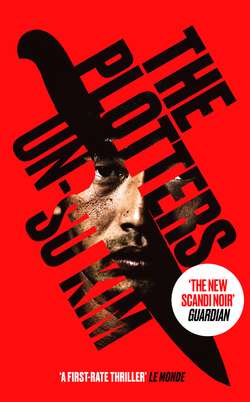

Читать книгу The Plotters - Un-su Kim - Страница 5

ON HOSPITALITY

ОглавлениеThe old man came out to the garden.

Reseng tightened the focus on the telescopic sight and pulled back the charging handle. The bullet clicked loudly into the chamber. He glanced around. Other than the tall fir trees reaching for the sky, nothing moved. The forest was silent. No birds took flight, no bugs chirred. Given how still it was out here, the noise of a gunshot would travel a long way. And if people heard it and rushed over? He brushed aside the thought. No point in worrying about that. Gunshots were common out here. They would assume it was poachers hunting wild boar. Who would waste their time hiking this deep into the forest just to investigate a single gunshot? Reseng studied the mountain to the west. The sun was one hand above the ridgeline. He still had time.

The old man started watering the flowers. Some received a gulp, some just a sip. He tipped the watering can with great ceremony, as if he were serving them tea. Now and then he did a little shoulder shimmy, as if dancing, and gave a petal a brief caress. He gestured at one of the flowers and chuckled. It looked like they were having a conversation. Reseng adjusted the focus again and studied the flower the old man was talking to. It looked familiar. He must have seen it before, but he couldn’t remember what it was called. He tried to recall which flower bloomed in October—cosmos? zinnia? chrysanthemum?—but none of the names matched the one he was looking at. Why couldn’t he remember? He furrowed his brow and struggled to come up with the name but soon brushed aside that thought, too. It was just a flower—what did it matter?

A huge black dog strolled over from the other end of the garden and rubbed its head against the old man’s thigh. A mastiff, purebred. The same beast Julius Caesar had brought back from his conquest of Britain. The dog the ancient Romans had used to hunt lions and round up wild horses. As the old man gave the dog a pat, it wagged its tail and wound around his legs, getting in his way as he tried to continue his watering. He threw a deflated soccer ball across the garden, and the dog raced after it, tail wagging, while the old man returned to his flowers. Just as before, he gestured at them, greeted them, talked to them. The dog came back immediately, the flattened soccer ball between its teeth. The old man threw the ball farther this time, and the dog raced after it again. The ferocious mastiff that had once hunted lions had been reduced to a clown. And yet the old man and the dog seemed well suited to each other. They repeated the game over and over. Far from getting bored, they looked like they were enjoying it.

The old man finished his watering and stood up straight, stretching and smiling with satisfaction. Then he turned and looked halfway up the mountain, as if he knew Reseng was there. The old man’s smiling face entered Reseng’s crosshairs. Did he know the sun was less than a hand above the horizon now? Did he know he would be dead before it dipped below the mountain? Was that why he was smiling? Or maybe he wasn’t actually smiling. The old man’s face seemed fixed in a permanent grin, like a carved wooden Hahoe mask. Some people just had faces like that—people whose inner feelings you could never guess at, who smiled constantly, even when they were sad or angry.

Should he pull the trigger now? If he pulled it, he could be back in the city before midnight. He’d take a hot bath, down a few beers until he was good and drunk, or put an old Beatles record on the turntable and think about the fun he’d soon have with the money on its way into his bank account. Maybe, after this final job, he could change his life. He could open a pizza shop across from a high school, or sell cotton candy in the park. Reseng pictured himself handing armfuls of balloons and cotton candy to children and dozing off under the sun. He really could live that life, couldn’t he? The idea of it suddenly seemed so wonderful. But he had to save that thought for after he pulled the trigger. The old man was still alive, and the money was not yet in his account.

The mountain was swiftly casting its shadow over the old man and his cabin. If Reseng was going to pull the trigger, he had to do it now. The old man had finished watering and would be going back inside any second. The job would get much harder then. Why complicate it? Pull the trigger. Pull it now and get out of here.

The old man was smiling, and the black dog was running with the soccer ball in its mouth. The old man’s face was crystal clear in the crosshairs. He had three deep wrinkles across his forehead, a wart above his right eyebrow, and liver spots on his left cheek. Reseng gazed at where his heart would soon be pierced by a bullet. The old man’s sweater looked hand-knit, not factory-made, and was about to be drenched in blood. All he had to do was squeeze the trigger just the tiniest bit, and the firing pin would strike the primer on the 7.62 mm cartridge, igniting the gunpowder inside the brass casing. The explosion would propel the bullet forward along the grooves inside the bore and send it spinning through the air, straight toward the old man’s heart. With the high speed and destructive force of the bullet, the old man’s mangled organs would explode out the exit wound in his lower back. Just the thought of it made the fine hairs all over Reseng’s body stand on end. Holding the life of another human being in the palm of his hand always left him with a funny feeling.

Pull it.

Pull it now.

And yet for some reason, Reseng did not pull the trigger and instead set the rifle down on the ground.

“Now’s not the right time,” he muttered.

He wasn’t sure why it wasn’t the right time. Only that there was a right time for everything. A right time for eating ice cream. A right time for going in for a kiss. And maybe it sounded stupid, but there was also a right time for pulling a trigger and a right time for a bullet to the heart. Why wouldn’t there be? And if Reseng’s bullet happened to be sailing straight through the air toward the old man’s heart just as the right moment fortuitously presented itself to him? That would be magnificent. Not that he was waiting for the best possible moment, of course. That auspicious moment might never come. Or it could pass by right under his nose. It occurred to him that he simply didn’t want to pull the trigger yet. He didn’t know why, but he just didn’t. He lit a cigarette. The shadow of the mountain was creeping past the old man’s cottage.

When it turned dark, the old man took the dog inside. The cottage must not have had electricity, because it looked even darker in there. A single candle glowed in the living room, but Reseng couldn’t make out the interior well enough through the scope. The shadows of the man and his dog loomed large against a brick wall and disappeared. Now the only way Reseng could kill him from his current position would be if the old man happened to stand directly in the window with the candle in his hand.

As the sun sank below the ridge, darkness descended on the forest. There was no moon; even objects close at hand were hard to make out. There was only the glimmer of candlelight from the old man’s cottage. The darkness was so dense that it made the air seem damp and heavy. Why didn’t Reseng just leave? Why linger there in the dark? He wasn’t sure. Wait for daybreak, he decided. Once the sun came up, he’d fire off a single round—no different from firing at the wooden target he’d practiced with for years—and then go home. He put his cigarette butt in his pocket and crawled into the tent. Since there was nothing else to do to pass the time, he ate a packet of army crackers and fell asleep wrapped up in his sleeping bag.

Reseng was awakened abruptly about two hours later by heavy footsteps in the grass. They were coming straight toward his tent. Three or four irregular thuds. A torso sweeping through tall grass. He couldn’t decipher what was coming his way. Could be a wild boar. Or a wildcat. Reseng disengaged the safety and pointed his rifle at the darkness, toward the approaching sound. He couldn’t pull the trigger yet. Mercenaries lying in wait had been known to fire into the dark out of fear, without checking their targets, only to discover that they’d hit a deer or a police dog or, worse, one of their fellow soldiers lost in the forest while out scouting. They would sob next to the corpse of a brother in arms felled by friendly fire, their beefy, tattooed bodies shaking like a little girl’s as they told their commanding officers, “I didn’t mean to kill him, I swear.” And maybe they really hadn’t meant to. Since they’d never before had to face their fear of things going bump in the night, the only thing someone with muscles for brains knew how to do was point and shoot into the dark. Reseng waited calmly for whatever was out there to reveal itself. To his surprise, what emerged was the old man and his dog.

“What are you doing out here?” the old man asked.

Now, this was funny. As funny as if the bull’s-eye at the firing range had walked right up to him and said, Why haven’t you shot me yet?

“What’re you doing out here? I could’ve shot you,” Reseng said, his voice trembling.

“Shot me? How’s that for turning the tables?” the old man said with a smile. “This is my land. You’re the one who doesn’t belong, crashing on someone else’s property.” He looked relaxed. The situation was unusual, to say the least, and yet he didn’t seem at all taken aback. Instead, the one taken aback was Reseng.

“You startled me. I thought you were a wild animal.”

“You’re a hunter?” the old man asked, looking pointedly at Reseng’s rifle.

“Yes.”

“That’s a Dragunov. You only see those in museums. So poachers these days hunt with Vietnam War rifles?”

“I don’t care how old the gun is as long as it can take down a boar.” Reseng tried to sound nonchalant.

“True. If it stops a boar, then it doesn’t matter what gun you use. Hell, if you can stop a boar with chopsticks—or a toothpick, for that matter—you can skip the gun altogether.”

The old man laughed. The dog waited patiently at his side. It was much bigger than it had looked through the scope. And much more intimidating than when it was chasing after a deflated soccer ball.

“That’s a nice dog,” Reseng said. The old man looked down at the dog and stroked its head.

“He is a nice dog. He’s the one who sniffed you out. But he’s old now.”

The dog never took its eyes off of Reseng. It didn’t growl or bare its teeth, but it wasn’t exactly friendly, either. The old man gave the dog’s head another pat.

“Since you insist on staying the night, don’t catch cold out here. Come to the house.”

“Thank you for the offer, but I wouldn’t want to trouble you.”

“It’s no trouble.”

The old man turned and strode back down the slope, the dog at his heels. He didn’t have a flashlight, but he seemed to have no trouble finding his way through the dark. Reseng’s mind was in a whirl. His rifle was charged and ready, and his target was only five meters away. He watched the old man disappear into the darkness. A second later, he shouldered the rifle and headed down after him.

The cottage was warm. A fire blazed in the redbrick fireplace. There were no furnishings or decorations, save for a threadbare rug and small table in front of the fire and a few photos on the mantelpiece. The photos were all of the old man, sitting or standing with others, always at the center of the group, the people at his sides smiling stiffly, as if honored to be photographed with him. None of the photos seemed to be of family.

“Kind of early in the year for a fire,” Reseng said.

“The older you get, the more you feel the cold. And I’m feeling it more than ever this year.”

The old man stuffed a few pieces of dry wood into the fire, the flames balking briefly at the new addition. Reseng unslung his rifle from his shoulder and leaned it against the doorjamb. The old man stole a glance at the gun.

“Isn’t October closed season for hunting?”

There was a twinkle in his eye. He’d been using banmal, the familiar form of speech, as if he and Reseng were old friends, but it didn’t bother Reseng.

“A man could starve to death trying to follow every law.”

“True, not all laws need to be followed,” the old man murmured. “You’d be stupid to try.”

As he stirred the logs with a metal poker, the flames rose and licked at a piece of wood that had not yet caught fire.

“Well, I’ve got booze and I’ve got tea, so pick your poison.”

“Tea sounds good.”

“You don’t want something stronger? You must’ve been freezing.”

“I don’t usually drink when I’m hunting. Besides, it’s dangerous to drink if you’re going to sleep outdoors.”

“Then indulge tonight,” the old man said with a smile. “Not much chance of freezing to death in here.”

He went to the kitchen and returned with two tin cups and a bottle of whiskey, then used a pair of tongs to carefully retrieve a kettle of black tea from inside the fireplace. He poured tea into one of the cups. His movements were smooth and measured. He handed the cup to Reseng and filled his own, then surprised Reseng by topping it off with whiskey.

“If you’re not warmed up yet, a touch of whiskey’ll get you the rest of the way. You can’t go hunting until daybreak anyway.”

“Does tea go with whiskey?” Reseng asked.

“Why not? It’s all the same going down.”

The old man wrinkled his eyes at him. He had a handsome face. He looked like he would have received a lot of compliments in his younger days. His chiseled features made him seem somehow tough and warm at the same time. As if the years had gently filed down his rough edges and softened him. Reseng held out his cup as the old man tipped a little whiskey into it. The scent of alcohol wafted up from the warm tea. It smelled good. The dog sauntered over from the other end of the living room and lay down next to Reseng.

“You’re a good person.”

“Pardon?”

“Santa likes you,” the old man said, gesturing at the dog. “Dogs know good people from bad right away.”

Up close, the dog’s eyes were surprisingly gentle.

“Maybe it’s just stupid,” Reseng said.

“Drink your tea.”

The old man smiled. He took a sip of his spiked tea, and Reseng followed suit.

“Not bad,” Reseng said.

“Surprising, huh? Tastes good in coffee, too, but black tea is better. Warms your stomach and your heart. Like wrapping your arms around a good woman,” he added with a childish giggle.

“If you’ve got a good woman, why stop at hugging?” Reseng scoffed. “A good woman is always better than some boozy tea.”

The old man nodded. “I suppose you’re right. No tea compares to a good woman.”

“But the taste is memorable, I’ll give you that.”

“Black tea is steeped in imperialism. That’s what gives it its flavor. Anything this flavorful has to be hiding an incredible amount of carnage.”

“Interesting theory.”

“I’ve got some pork and potatoes. Care for some?”

“Sure.”

The old man went outside and came back with a blackened lump of meat and a handful of potatoes. The meat looked awful. It was covered in dirt and dust and still had patches of hair, but even worse was the rancid smell. He shoved the pork into the hot ash at the bottom of the fireplace until it was completely coated, then skewered it on an iron spit and propped it over the fire. He stirred the flames with the poker and tucked the potatoes into the ash.

“I can’t say that looks all that appetizing,” Reseng said.

“I lived in Peru for a while. Learned this method from the Indians. Doesn’t look clean but tastes great.”

“Frankly, it looks pretty terrible, but if it’s a secret native recipe, then I guess there must be something to it.”

The old man grinned at Reseng.

“Just a few days ago, I discovered something else I have in common with the native Peruvians.”

“What’s that?”

“No refrigerator.”

The old man turned the meat. His face looked earnest in the glow of the fire. As he pricked the potatoes with a skewer, he murmured at them, “You’d better make yourselves delicious for our important guest.” While the meat cooked, the old man finished off his spiked tea and refilled his cup with just whiskey, then offered more to Reseng.

Reseng held out his cup. He liked how the whiskey burned on its way down his throat and radiated smoothly up from his empty stomach. The alcohol spread pleasantly through his body. For a moment, everything felt unreal. He would never have imagined it: a sniper and his target sitting in front of a roaring fire, pretending to be best friends … Each time the old man turned the meat, a delicious aroma wafted toward him. The dog moved closer to the fireplace to sniff at the meat, but he hung back at the last moment and grumbled instead, as if afraid of the fire.

“There, there, Santa. Don’t worry,” the old man said, patting the dog. “You’ll get your share.”

“The dog’s name is Santa?”

“I met this fellow on Christmas Day. That day, he lost his owner and I lost my leg.”

The old man lifted the hem of his left pant leg to reveal a prosthesis.

“He saved me. Dragged me over nearly five kilometers of snow-covered road.”

“That’s a hell of a way to meet.”

“Best Christmas gift I ever got.”

The old man continued to stroke the dog’s head.

“He’s very gentle for his size.”

“Not exactly. I used to have to keep him leashed all the time. One glimpse of a stranger and he’d attack. But now that he’s old, he’s gone soft. It’s odd. I can’t get used to the idea of an animal being this friendly with people.”

The meat smelled cooked. The old man poked at it with the skewer and took it off the fire. Using a serrated knife, he carved the meat into thick slices. He gave a piece to Reseng, a piece to himself, and a piece to Santa. Reseng brushed off the ash and took a bite.

“What an unusual flavor. Doesn’t really taste like pork.”

“Good, yeah?”

“It is. But do you have any salt?”

“Nope.”

“No fridge, no salt—that’s quite a way to live. Do the native Peruvians also live without salt?”

“No, no,” the old man said sheepishly. “I ran out a few days ago.”

“Do you hunt?”

“Not anymore. About a month ago, I found a wild boar stuck in a poacher’s trap. Still alive. I watched it gasp for breath and thought to myself, Do I kill it now or wait for it to die? If I waited for it to die, then I could blame its death on the poacher who left that trap out, but if I killed it, then I’d be responsible for its death. What would you have done?”

The old man’s smile was inscrutable. Reseng gave the tin cup a swirl before polishing off the alcohol.

“Hard to say. I don’t think it really matters who killed the boar.”

The old man seemed to ponder this for a moment before responding.

“I guess you’re right. When you really think about it, it doesn’t matter who killed it. Either way, here we are enjoying some Peruvian-style roasted boar.”

The old man laughed loudly. Reseng laughed, too. It wasn’t much of a joke, but the old man kept laughing, and Reseng followed suit with a loud laugh of his own.

The old man was in high spirits. He filled Reseng’s cup with whiskey until it was nearly overflowing, then filled his own and raised it in a toast. They downed their drinks in one gulp. The old man picked up the skewer and fished a couple of potatoes from the hot ashes. After taking a bite of one, he pronounced it delicious and gave the other to Reseng. Reseng brushed off the ashes and took a bite. “That is delicious,” he said.

“There’s nothing better than a roasted potato on a cold winter’s day,” the old man said.

“Potatoes always remind me of someone …” Reseng started to babble. His face was red from the alcohol and the glow of the fire.

“I’m guessing this story doesn’t have a happy ending,” the old man said.

“It doesn’t.”

“Is that someone alive or dead?”

“Long dead. I was in Africa at the time, and we got an emergency call in the middle of the night. We jumped in a truck and headed off. It turned out that a rebel soldier who’d escaped camp had taken an old woman hostage. He was just a kid—still had his baby fat. Must’ve been fifteen, maybe even fourteen? From what I saw, he was worked up and scared out of his wits, but not an actual threat. The old woman kept saying something to him. Meanwhile, he was pointing an AK-47 at her head with one hand and cramming a potato into his mouth with the other. We all knew he wasn’t going to do anything, but then the order came over the walkie-talkie to take him out. Someone pulled the trigger. We ran over to take a closer look. Half of the kid’s head was blown away, and in his mouth was the mashed-up potato that he never got the chance to swallow.”

“The poor thing. He must’ve been starving.”

“It felt so strange to look into the mouth of a boy with half his head missing. What would’ve happened if we’d waited just ten more seconds? All I could think was, If we had waited, he would’ve been able to swallow the potato before he died.”

“Not like anything would’ve changed for that poor boy if he had swallowed it.”

“No, of course not.” Reseng’s voice wavered. “But it still felt weird to think about that chewed-up potato in his mouth.”

The old man finished the rest of his whiskey and poked around in the ashes with the skewer to see if there were any more potatoes. He found one in the corner and offered it to Reseng, who gazed blankly at it and politely declined. The old man looked at the potato; his face darkened and he tossed it back into the ashes.

“I’ve got another bottle of whiskey. What do you say?” the old man asked.

Reseng thought about it for a moment. “Your call,” he said.

The old man brought another bottle from the kitchen and poured some for him. They sipped in silence as they watched the flames dance in the fireplace. As Reseng grew tipsy, a feeling of profound unreality washed over him. The old man’s eyes never left the fire.

“Fire is so beautiful,” Reseng said.

“Ash is more beautiful once you get to know it.”

The old man slowly swirled his cup as he gazed into the flames. He smiled then, as if recalling something funny.

“My grandfather was a whaler. This was back before they outlawed whaling. He didn’t grow up anywhere near the ocean—he was actually from inland Hamgyong Province, but he went down south to Jangsaengpo harbor for work and ended up becoming the best harpooner in the country. During one of the whaling trips, he got dragged under by a sperm whale. Really deep under. What happened was, he threw the harpoon into the whale’s back, but the rope tangled around his foot and pulled him overboard. Those flimsy colonial-era whaling boats and shoddy harpoons were no match for an animal that big. A male sperm whale can grow up to eighteen meters long and weigh up to sixty tons. Think about it. That’s like fifteen adult African elephants. I don’t care if it were just a balloon animal—I would never want to mess with anything that big. No way, no how. But not my grandfather. He stuck his harpoon right in that giant whale.”

“What happened next?” Reseng asked.

“Utter havoc, of course. He said the shock of falling off the bow made him woozy, and he couldn’t tell if he was dreaming or hallucinating. Meanwhile, he was being dragged helplessly into the dark depths of the ocean by a very angry whale. He said the first thing he saw when he finally snapped out of his daze was a blue light coming off the sperm whale’s fins. As he stared at the light, he forgot all about the danger he was in. When he told me the story, he kept going on about how mysterious and tranquil and beautiful it was. An eighteen-meter-long behemoth coursing through the pitch-black ocean with glowing blue fins. I tried to break it to him gently—he was practically in tears just recalling it—that since whales are not bioluminescent, there was no way its fins could have glowed like that. He threw his chamber pot at my head. Ha! What a hothead! He told the story to everyone he met. I told him everyone thought he was lying because of the part about the fins. But all he said to that was, ‘Everything people say about whales is a lie. Because everything they say comes from a book. But whales don’t live in books, they live in the ocean.’ Anyway, after the whale dragged him under, he passed out.”

The old man refilled his cup halfway and took a sip.

“He said that when he came to, there was a big full moon hanging in the night sky, and waves were lapping at his ear. He thought luck was on his side and the waves had pushed him onto a reef. But it turned out he was on top of the whale’s head. Incredible, wouldn’t you say? There he was, lying across a whale, staring at a buoy, a growing pool of the whale’s slick red blood all around him, and the whale itself, propping him up out of the water with its head, that harpoon still sticking out of its back. Can you imagine anything stranger or more incomprehensible? I’ve heard of whales lifting an injured companion or a newborn calf out of the water so they can breathe. But this wasn’t a companion or a baby whale, or even a seal or a penguin. It was my grandfather, a human being, and the same person who’d shoved a harpoon in its back! I honestly don’t understand why the whale saved him.”

“No, it doesn’t make any sense,” Reseng said, taking a sip of whiskey. “You’d think that whale would have torn him apart.”

“He just lay there on the whale’s head for a long time, even after he’d regained consciousness. It was awkward, to say the least. What can you do when you’re stuck on top of a whale? There was nothing out there but the silvery moon, the dark waves, a sperm whale spilling buckets of blood, and him—well and truly up shit creek. My grandfather said the sight of all that blood in the moonlight made him apologize to the whale. It was the least he could do, you know? He wanted to pull out the harpoon, too, but easier said than done. Throwing a harpoon is like making a bad life decision: so easy to do, but so impossible to take back once the damage is done. Instead, he cut the line with the knife he kept on his belt. The moment he cut it, the whale dove and resurfaced some distance away, then headed straight back to where my grandfather was clinging to the buoy, struggling to stay afloat. He said it watched as he flailed pathetically, filled with shame, all tangled up in the line from the harpoon he himself had thrown. According to my grandfather, the beast came right up and gazed at him with one enormous dark eye, a look of innocent curiosity that seemed to say, How did such a little scaredy-cat like you manage to stick a harpoon in the likes of me? You’re braver than you look! Then, he said, it gave him a playful shove, as if to say, Hey, kid, that was pretty naughty. Better not pull another dangerous stunt like that! All the blood it had lost was turning the water murky, and yet it seemed to brush off the whole matter of my grandfather stabbing it in the back. Each time my grandfather got to this part of the story, he used to slap his knee and shout, ‘That monster’s heart was as big as its body! Completely different from us small-minded humans.’ He said the whale stayed by his side all night, until the whaleboat caught up to them. The other whalers had been tracking the buoys in search of my grandfather. As soon as the ship appeared in the distance, the whale swam in a circle around him, as if it were saying good-bye, and then dove again, even deeper than before, the harpoon with my grandfather’s name carved into it still quivering in its back. Incredible, huh?”

“Yeah, that’s quite a story,” Reseng said.

“I guess that after that narrow escape from a watery death, my grandfather had some serious second thoughts about whaling. He told my grandmother he didn’t want to go back. My grandmother was a very kind and patient woman. She hugged him and said if he hated catching whales that much, then he should stop. He said he sobbed like a baby in her arms and told her, ‘I felt so scared, so terribly scared!’ And then he really did keep his distance from whaling for a while. But those crybaby days of his didn’t last long. They were poor, there were too many mouths to feed, and whaling was the only trade he’d ever learned. He didn’t know how else to provide for all those hungry children squawking at him like baby sparrows. So he went back to work and launched his harpoon at every whale he saw in the East Sea until he retired at the age of seventy. But there was one more funny thing that happened: In 1959, he ran into the same sperm whale again. Exactly thirty years after his miraculous survival. His rusted old harpoon was still stuck in its back, but the whale was just swimming along, all gallant and free, as if that harpoon had always been there and were simply a part of its body. Actually, it’s not uncommon to hear about whales surviving long after a harpoon attack. They even say that once, in the nineteenth century, a whale was caught with an eighteenth-century harpoon still stuck in it. Anyway, the whale didn’t swim off when it saw the whaling ship; in fact, it cruised right up to my grandfather’s boat, the harpoon sticking straight up like a periscope, and slowly circled it. As if it were saying, Hey! Long time no see, old friend! But what’s this? Still hunting whales? You really don’t know when to quit, do you?” The old man laughed.

“Your grandfather must have felt pretty embarrassed,” Reseng said.

“You bet he did. The sailors said my grandfather took one look at that sperm whale and dropped to his knees. He threw himself on the deck and let out a howl. He wept and called out, “Whale, forgive me! I’m so sorry! How awful for you, swimming all those years with a harpoon stuck in your back! After we said good-bye, I wanted to stop, I swear. You probably don’t know this, since you live in the sea, but things have been really tough up on land. I’m still living in a rental, and my brats eat so much, you’d be shocked at what it costs to feed them. I had to come back because I could barely make ends meet. Forgive me! Let’s meet again and have a drink together. I’ll bring the booze if you catch us a giant squid to snack on. Ten crates of soju and one grilled giant squid should do it. I’m so sorry, Whale. I’m sorry I stabbed you in the back with a harpoon. I’m sorry I’m such a fool. Boo-hoo-hoo!’”

“Did he really yell all of that at the whale?” Reseng asked.

“They say he really did.”

“He was a funny guy, your grandfather.”

“He was indeed. Anyway, after that, he gave up whaling and left Jangsaengpo harbor for good. He came up to Seoul and spent all his time drinking. I imagine he felt pretty trapped, given that he couldn’t go out to sea anymore, and with barbed wire strung all across the thirty-eighth parallel, he couldn’t go back north to his hometown, either. So whenever he got drunk, he latched on to people and started up with that same boring old whale tale. He told it over and over, even though everyone had already heard it hundreds of times and no one wanted to hear it again. But he wasn’t doing it to brag about his adventures on the high seas. He believed that people should emulate whales. He said that people had grown as small and crafty as rats, and that the days of taking slow, huge, beautiful strides had vanished. The age of giants was over.”

The old man swigged his whiskey. Reseng refilled his cup and took a sip.

“Toward the end, he found out he was in the final stages of liver cancer. It wasn’t exactly a surprise. As a sailor, he’d been guzzling booze from the age of sixteen to the age of eighty-two. But I guess the news meant nothing at all to him, because no sooner did he return from seeing the doctor than he hit the bottle again. He gathered his kids together and told them, ‘I’m not going to any hospital. Whales accept it when their time comes.’ And he never did go back to the doctor. After about a month, my grandfather put on his best clothes and returned to Jangsaengpo harbor. According to the sailors there, he loaded a small boat up with ten crates of soju, just like he’d said he would, and rowed until he disappeared over the horizon. And he never came back. His body was never found. Maybe he really did row until he caught the scent of ambergris and tracked down his whale. If he did, then I’m sure he broke open all ten crates of soju that night as they caught up on the years they’d missed, and if he didn’t, then he probably drifted around the ocean, drinking alone, until he died. Or maybe he’s still out there somewhere.”

“That’s quite an ending.”

“It’s a dignified way to go. In my opinion, a man ought to be able to choose a death that gives his life a dignified ending. Only those who truly walk their own path can choose their own death. But not me. I’ve been a slug my whole life, so I don’t deserve a dignified death.”

The old man smiled bitterly. Reseng was at a loss for a response. The look on the old man’s face was so dark that Reseng felt compelled to say something comforting, but he really couldn’t think of what to say. The old man refilled his cup with whiskey and polished it off again. They sat there for a long time. Each time the flames died down, Reseng added more wood to the fire. While Reseng and the old man sipped whiskey in comfortable silence, each new piece caught fire, crackled and flared up hot and ferocious, then slowly burned down to glowing charcoal, and then to white ash.

“I really talked your ear off tonight. They say the older you get, the more you’re supposed to keep your purse strings open and your mouth shut.”

“Oh, no, I enjoyed it.”

The old man shook the whiskey bottle and eyed the bottom. There was only about a cup left.

“Mind if I finish this off?”

“Go right ahead,” Reseng said.

The old man poured the rest of the whiskey into his cup and downed it.

“We’d better call it a night. You must be exhausted. I should’ve let you sleep, but instead I kept talking.”

“No, it was a nice evening, thanks to you.”

The old man curled up on the floor to the right of the fireplace. Santa sauntered over and lay down next to him. Reseng lay down to the left of the fireplace. The shadows of the two men and the dog danced on the brick wall opposite them. Reseng looked at his rifle propped against the door.

“Have some breakfast before you leave tomorrow,” the old man said, rolling onto his side. “You don’t want to hunt on an empty stomach.”

Reseng hesitated before saying, “Of course, I’ll do that.”

The crackling fire and the dog’s steady breaths sounded unusually loud. The old man didn’t say another word. Reseng listened for a long time to the old man and the dog breathing in their sleep before he finally joined them. It was a peaceful sleep.

When he awoke, the old man was preparing breakfast. A simple meal of white rice, radish kimchi, and doenjang soup made with sliced potatoes. The old man didn’t say much. They ate in silence. After breakfast, Reseng hurried to leave. As he stepped out the door, the old man handed him six boiled potatoes wrapped in a cloth. Reseng took the bundle and bade him a polite farewell. The potatoes were warm.

By the time Reseng returned to his tent, the old man was watering the flowers again. Just as before, he tipped the watering can with care, as if pouring tea. Then, just as before, he spoke to the flowers and trees and gestured at them. Reseng made a minor adjustment to the scope. The familiar-looking flower grew sharp and distinct in the lens and blurred again. He still could not remember its name. He should have asked the old man.

It was a nice garden. Two persimmon trees stood nonchalantly in the courtyard, while the flowers in the garden beds waited patiently for their season to come. Santa went up to the man and rubbed his head against the man’s thigh. The old man gave the dog a pat. They suited each other. The old man threw the deflated soccer ball across the garden. While Santa ran to fetch it, the old man watered more flowers. What was he saying to them? On closer inspection, he did indeed have a slight limp. If only Reseng had asked him what had happened to his left leg. Not that it makes any difference, he thought. Santa came back with the ball. This time, the old man threw it farther. Santa seemed to be in a good mood, because he ran around in circles before racing off to the end of the garden to fetch the ball. The old man looked like he had finished watering. He put down the watering can and smiled brightly. Was he laughing? Was that carved wooden mask of a face really laughing?

Reseng fixed the crosshairs on the old man’s chest and pulled the trigger.