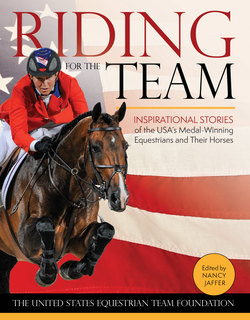

Читать книгу Riding for the Team - United States Equestrian Team Foundation - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеRobert Ridland

A Californian Comes to Gladstone

After a West Coast screening trial for U.S. Equestrian Team candidates, Robert Ridland was selected by show jumping Coach Bertalan de Némethy to train at the team’s Gladstone, New Jersey, headquarters.

Bert was a graduate of the Hungarian cavalry school and had served in World War II, so everything was done with military precision and according to impeccable standards at the historic stables when Robert rode there in the 1970s. The facility was recognized worldwide as the base for such renowned riders as team captain William Steinkraus, Frank Chapot (who would succeed Bert as coach), Kathy Kusner, and George Morris.

Robert was the reserve rider at the 1972 Olympics in Munich and rode on the 1976 fourth-place Montreal Olympic team, as well as winning Nations Cup teams at Lucerne in 1976 and in Rotterdam and Toronto in 1978. In 2012, Robert became coach of the U.S. Show Jumping Team, with a stellar record that includes team and individual bronze medals at the 2014 FEI World Equestrian Games, team bronze and individual gold and bronze at the 2015 Pan American Games, team silver at the 2016 Olympics, and team gold at the 2018 WEG—the first gold for the U.S. team at a World Championships in 32 years.

The president of show management company Blenheim EquiSports, Robert has served as a member of the U.S. Equestrian Federation board of directors and the FEI Jumping Committee. An international course designer who also has been a World Cup finals technical delegate, the Yale University graduate has run the Las Vegas World Cup finals and was co-manager of the Washington International Horse Show.

Robert and his wife, Hillary, who live in California, have two children, Peyton and McKenna.

The few of us left who once were part of the old U.S. Equestrian Team, the original concept, can look at show jumping with a unique perspective to compare it with where the sport is today. So much time has passed that there are not that many current riders who are familiar with where the sport came from and the circumstances that led to what it has become.

Having Coach Bertalan de Némethy go around the country to select riders with potential was a totally different system than what we have now. Another difference was the fact that we didn’t have private owners to the degree that we do today. The top horses in the country were owned by the USET or loaned to the team, and we got matched with the ones we were going to ride.

U.S. Equestrian Team Coach Bertalan de Némethy with (left to right) Robert Ridland, Dennis Murphy, Michael Matz, and Buddy Brown after winning the 1978 Nations Cup in Rotterdam.

When I got to team headquarters in Gladstone, I was young, only 18, and already enrolled at Yale. I was well prepared by my riding and competition experience to that point and had ridden at shows in the East. Even so, there was a bit of culture shock.

The first time I met Bert was when he was in California for the screening trials. Bert was Hungarian nobility and very old world; I was very West Coast and didn’t leave my California ways at home. It was quite a proving ground.

Robert Ridland guided the United States to two bronze medals in his first world championships coaching gig at the 2014 FEI World Equestrian Games.

The riders in training lived in rooms over the team stables. One of the many requirements involved always dressing appropriately in boots and breeches. It also meant making sure they were clean. A few times, we had to have the washer and dryers working on our breeches at the last minute before we got on the horses in the morning.

I wasn’t really prepared for winter, having grown up with California’s sunny version of the season. I will never forget a particularly cold morning when there was only time to wash the breeches, not dry them. And that was a problem, because at the time, I had just one pair of breeches (something I rectified soon after).

Once we got outside, my breeches basically froze. We were riding on the flat in the indoor ring. Bert was there in front of this jet engine of a heater that was blasting at him! He was wearing this heavy overcoat and looked as if he could survive the Arctic, while I was practically shivering.

George Simmons, the barn manager, had been in the military and ran the place like a Marine sergeant. He gave us all lessons in tack cleaning. I had thought I was pretty good at it—that is, until I ran into George at Gladstone. And Dennis Haley, one of the grooms there, also was meticulous about making sure we cleaned our tack according to the team’s requirements.

I was lucky enough to be taken under the wing of our team captain, Bill Steinkraus, the Olympic individual gold medalist who was one of the greatest riders of all time. When I first rode on the team, Billy was my mentor in so many ways. He needed someone to go golfing with, so he taught me how to play on our off days.

That gave us a lot of time to talk, and I was always watching how he approached the sport. I remember my first couple of shows in Europe when I joined the team. We got to Lucerne, Switzerland, which was the third one. As we were sitting on the Volkswagen bus being driven to the showgrounds, Billy turned around to us and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, now we start.”

I’ll never forget that because I thought we had started two weeks earlier. But Lucerne was the important Nations Cup, with the honor of our country riding on our performance.

Billy was all the things that everyone said about him—the class he brought to the sport, the sense of perfectionism. Billy never compromised on anything. He was the sport.

The thing that impresses me in retrospect about my experience at Gladstone is how young we all were at the time. I rode on my first international team when I was 19 years old. A couple of years later, Buddy Brown rode on his first team when he was 18 and won the Grand Prix at Dublin. Michael Matz was my age as well.

After my years with the team, however, there seemed to be a trend, not just in the United States, but in other countries as well, to have older riders—and the same riders—constantly on their team. The British, before they turned things around and won gold at the 2012 London Olympics, fielded lots of squads with riders who were older, and that was detrimental.

When I came in as U.S. coach, I said, “We’re going to use the riders who were our age when we started competing.” There’s no reason in the world why you would have to wait until you were in your late twenties or early thirties to bring something to the table from the point of view of international competitions.

While the USET ran things at the international end of the sport for America when I was riding, having stepped in to replace the cavalry after World War II, today everyone, in effect, has his or her own private professional team. That means we don’t just select the rider, we embrace not only the rider, but also the owners, and all the support staff behind the horses.

These teams operate the same way Gladstone did in its heyday. An example is Beezie Madden, the Olympic and WEG medalist, who works with her husband, John. He grew up in Gladstone just like I did, except that he was a groom there. He started his career from the bottom up, which is why he is so good at what he does. He was immersed in Bert’s program—his system, his standards—from the very beginning…from polishing the brass to cleaning the tack.

Bert would come downstairs for inspection and all of us were there to make sure the horses were turned out appropriately and everything was done right. John took that knowledge and the other knowledge he gained through his career to establish with Beezie what they have today at their business in New York State. It’s a mini-Gladstone that didn’t just develop out of thin air. Bert’s system lives on, even though it’s not all under one roof in New Jersey.

At the 2012 Olympics, Robert Ridland consulted with Beezie Madden as he was learning the ropes.

It was a big change when we went from the team structure of my era to the professional sport we have today, but in many ways, it’s the same at the top level. Our top professional riders have the same degree of perfection and control of the details that Bert oversaw in Gladstone.

Since that job already is taken care of by our top riders, I don’t have to look over their shoulders and micro-manage every single professional. What I have to do is manage the chess pieces, and that’s a completely different job. I have to make sure what the objectives are, as well as how we get there and how each rider has the priorities for reaching that goal. Those priorities are, of course, different from the priorities of individual riders and owners. My job is to mesh the two together.

While I may lead the way, I’m not going solo on this. The U.S. Equestrian Federation in effect also has its own team, from Lizzy Chesson, the Managing Director of Show Jumping, to my Assistant Coach, Olympic medalist Anne Kursinski, and Young Rider Chef d’Equipe DiAnn Langer, as well as members of the USEF committees who work on behalf of the sport’s best interests.

From the horse side, some things haven’t changed. Over-competing and not adhering to a strict schedule of long-term goals and long-term scheduling still will be detrimental. Bert knew what our schedule was in the beginning of the year, as well as when the training sessions would be. He knew when we would select the team for Europe, when we would prepare for Europe, what shows we would do in Europe, which Nations Cups we were going to compete in, what the fall circuit would be. He was always 12 months ahead of time in his planning.

I do the same thing, but I do it with each individual rider instead of with a group. Unless our objectives are very clear about what our priorities are, it’s too easy to add a little too much to the schedule because the world is so much different in our sport from Bert’s time.

The opportunities to compete in big money Grands Prix have proliferated. Even in our own country, the number of FEI events has ballooned. It’s really crucial that the riders who are part of this program, who we feel can really contribute to the team’s important goals and markers we have for the year, stick to the plan and the schedule. That’s what I do in the early weeks of each year at the winter circuits in Florida and California, getting together with each rider to develop the plans so we can stick with them. I have always stressed that I will defer to sound horsemanship and long-term planning over short-term results.

What has made a huge difference for my job is technology. I can monitor the riders and watch their Grands Prix performances from my office. I’m seeing live-stream Grands Prix from Europe and all over the world from there. That helps me spend more time at home than I would have if I were doing this job in the 1970s or ‘80s.

At competitions, we go in there one horse at a time, one rider at a time, and it’s our course to do. What I pay attention to is how we can be our best and lay down as many clean rounds as we can. If we do that, we’ll be in a good position—it doesn’t really matter who we’re up against.

We have had a situation where it was felt that in order to really compete, you had to be in Europe. For us to be and remain competitive for the next 20 years, we need to truly level the playing field so people don’t feel they have to go to Europe in order to compete at the highest level. While I like to see the best competitors spending more time riding in the United States, that doesn’t mean we should never show in Europe. But if the top riders are always in Europe, it means they are not in the U.S., inspiring a new generation of riders and generating star power for the discipline.