Читать книгу Frances E. W. Harper - Utz McKnight - Страница 7

1 Frances Harper’s Poetic Journey A life of consciences

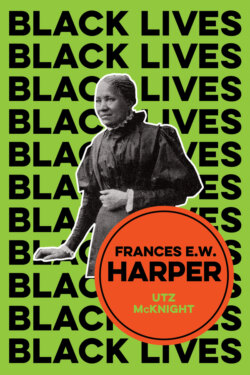

ОглавлениеWe are always writing for the present, for those who share the concerns and anxieties of our lives. But, of course, we can’t know how what we say and do today is measured by those who come after us, in spite of our desire to inhabit the thoughts and concerns of those who follow. Frances Harper – author, abolitionist, orator, political organizer, temperance activist, suffragist, mother, Black, American, woman – she dedicated her life to the politics of racial and gender justice.

Frances Harper was born in 1825 and lived an incredible life, sharing her ideas and her creativity with an American public until her death in 1911. She grew up a free Black person in a society where the majority of Black people were enslaved. The writer of the first short story published by an African American woman, Frances Harper also produced Iola Leroy, one of the most popular fiction novels in the US of the latter half of the nineteenth century. She was an accomplished and popular poet, and was able to make a living on the sale of her poetry at a time when it was not possible for a Black person to find a position at a university. An important orator and organizer for the Abolitionist Movement, the Temperance Movement, and the Suffragist Movement, Frances Harper was an activist – what we today call a public intellectual – with the tenacity and skill to remain at the center of the sweeping political changes that occurred in her lifetime. She was frequently published in the leading African American newspapers and magazines, contributing her ideas to a wide public in the society (Peterson, 1997).

What Harper couldn’t know is that, by the latter part of the twentieth century, her own contributions would be largely obscured by the very forces of racism and sexism that she fought against all her life (Foster, 1990). Each discovery today of the wealth of contributions made historically by Black women in the society is a mandate to again center these voices integral to the American democratic project, who, because of the politics of their time, were obscured or have subsequently had their contributions largely erased. We can only wonder how much of what was achieved by those living before us is unrecoverable; how much of what was accomplished has been erased by disfavor, disinterest, simple neglect, and the prejudices of popular opinion. Our history is derived from the imagination of those who would silence and vilify certain persons, groups, and causes. What ideas and work remain available from our past? What should we think today in a time when racial and gender inequality still remain definitive of American society?

What we do know is that, until the work of Black feminist researchers in the last four decades, much of the writing of Frances Harper was unavailable and thought lost. It is only through the work of these scholars, the diligent work of recovery and preservation, that we now have access, as well as to her popular novel Iola Leroy, to Harper’s three serialized novels, the work Fancy Sketches, many of her speeches, and the majority of her poetry. We owe a great debt to this research movement, by Black women working as established scholars, independent researchers, librarians, and activists. This dedication to recovering a Black past before the nadir in the late 1880s, and the decades of terror that described the time of lynching and Jim Crow, asks us as readers of Frances Harper’s work to question how we consider race and the contribution of Black people today in this society.

Even if the proximate causes have changed, the general social concerns that occupied Frances Harper are shared by us today. She can serve as an inspiration for both creative writing and political engagement. She demonstrates what was possible to do as an individual in a society where Black community members were enslaved and where women were not able to vote. What would it mean for us to live alongside those who remind us of the terrible oppression possible for us as well, to interact with those who share the burden of social descriptions of racial inferiority, even as our political status differentiates us? We know.

Today more Black people are in prison than were enslaved in 1825, and one out of three Black male adults will be incarcerated at some point in their lives. With large numbers of African Americans living in poverty, and a perception of racial inferiority that persists, with significant pay differentials between men and women, and #MeToo a necessity, the words of and life led by Harper provide encouragement and an example of how we might also thrive. The timeline for Harper’s life covers not only the last half of the nineteenth century, when the new nation sought to define its major institutions, but also the last decades of the centuries-long enslavement of Black people, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. She was present as the Western US opened up to settlement, and in the period of national development that saw rapid industrial growth, and then the portion of the late nineteenth century that, because of the establishment of Jim Crow laws and lynching, many consider the nadir of the free African American experience in the US.