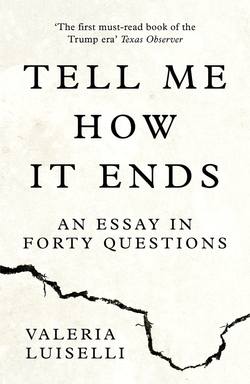

Читать книгу Tell Me How it Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions - Valeria Luiselli - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеIn Tell Me How It Ends there are no answers, only more questions. In this urgent, haunting, exquisitely written little book, the questions asked by Valeria Luiselli are her own, her children’s, and those she finds on the questionnaire drawn up by immigration attorneys for the tens of thousands of Central American children who arrive in the United States each year after being smuggled across Mexico to the U.S. border. These children are the most vulnerable members of an ongoing exodus of Central Americans fleeing poverty and violence in their shattered nations in the expectation of finding a better life in the United States. Many of the children are raped, robbed, or even killed along the way.

As a Mexican woman living in the United States, facing her own travails with the immigration service for a green card that would grant her U.S. residency and permission to work, Luiselli became transfixed by the surge of child refugees during the summer of 2014. She began working as an interpreter with an immigration court in New York City, where she was given the task of assisting the children with the intake questionnaire, asking its questions of them in Spanish and then translating their answers. Depending on those answers, they might or might not be granted legal sanctuary of some sort—and thus a future—in the United States. Luiselli soon realized it was impossible to fit the children’s lives neatly into the boxes provided, observing, “The children’s stories are always shuffled, stuttered, always shattered beyond the repair of a narrative order. The problem with trying to tell their story is that it has no beginning, no middle, and no end.”

The result of Luiselli’s experience is this book, in which the questions posed to the refugee children become catalysts for her own questions about the nature of family, childhood, and community, and above all, about national identity and belonging. She offers a fascinating rumination on the complex nature of the attraction of the United States for the refugee children and their families—and even for herself—despite its unwelcoming nature, casual racism, and official disinterest in their very existence. “Before coming to the United States, I knew what others know: that the cruelty of its borders was only a thin crust, and that on the other side a possible life was waiting,” she concludes. “I understood, some time after, that once you stay here long enough, you begin to remember the place where you originally came from the way a backyard might look from a high window in the deep of winter: a skeleton of the world, a tract of abandonment, objects dead and obsolete. And once you’re here, you’re ready to give everything, or almost everything, to stay and play a part in the great theater of belonging.”

Luiselli’s book appears during an especially raw juncture in the relationship between her birthplace, Mexico, and her adoptive home, the United States. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign, the nature of the relationship between the two countries became an essential plank in the candidacy of Republican billionaire Donald Trump, who notoriously referred to Mexicans as unwelcome intruders, as “criminals, drug dealers, and rapists” and called for a wall to be built along the border, one that, in an apparent effort to be as humiliating as possible, he insisted “Mexico will pay for.”

In this hallucinatory global political climate, in which bigoted notions about national identity, sect, and race have reared their heads to a degree not seen in many decades, Trump’s statements gained him a sizeable American following. It is distressingly clear that the fears and hatreds he has unleashed—especially since he, and not Hillary Clinton, won the election to become president—will not be easily put to rest. What does this mean for the refugee children and their families who flee shattered communities to the United States, hoping to make themselves whole again? Luiselli does not know, but she feels certain that whatever their reception in the United States, the children will keep coming as long as there is a need to escape from realities too frightening to bear. “Children run and flee. They have an instinct for survival, perhaps, that allows them to endure almost anything just to make it to the other side of horror, whatever may be waiting there for them.” And what awaits them is a bewildering and often daunting reality, with little in the way of guidance to help them adapt. After six months adjusting to life in a tough neighborhood of New York, one Honduran youngster tells Luiselli what he has learned thus far: his new home “is a shithole full of pandilleros, just like Tegucigalpa.”

In the course of her work, Luiselli’s young daughter has heard about some of the children’s stories, and she repeatedly asks, as children do, “Tell me how it ends, Mamma.” Luiselli has no answers for her. There are, as yet, no happy endings, but toward the end of the book she offers a small hint of promise. It comes in the form of a decision by ten young Americans, just a few years older than the children of the intake questionnaires, to form a group that will help teenage refugees who have made it to the United States and managed to stay.

This is a profoundly moving book, one that, with its modest hundred pages and simple, teasing title, presents itself as a mere story guided by forty questions. But appearances are, after all, beguiling, and this is a most powerful story, beautifully told by Valeria Luiselli. I feel sure that whoever reads it will not regret it, nor easily forget it.

Jon Lee Anderson

Dorset, England

January 14, 2017