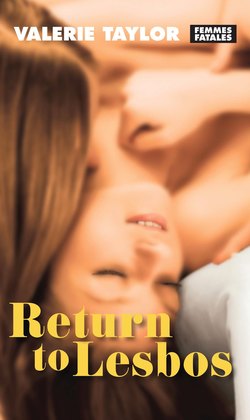

Читать книгу Return to Lesbos - Valerie Taylor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4 SHE LAY AWAKE FOR A LONG TIME AFTER BILL rolled over to his own side of the bed, turned his face to the wall and began to snore. The male smell was on her, the events of the last half hour were clear in her mind, yet it all seemed unreal, like something seen in the movies. She thought, I really am a whore. And she didn’t care.

At last she got up, too restless to lie still anymore and afraid that her turning would wake Bill. She showered, put on her old terry robe, and went downstairs, feeling her way along stair railings and groping for doorknobs in the still-unfamiliar house. Under the bright overhead light of the kitchen she made coffee and sat writing shopping lists while it perked. Things she needed for the house: a sofa, rugs, curtains, a telephone stand. Things she needed for herself: a light jacket, gloves, shampoo. In the morning she would read it all over and decide how much of it made sense; she always felt wide-awake and alert at this hour, but in the light of day her ideas sometimes looked quite different.

She knew, in the back of her mind, why she was doing all this. With a handful of lists she had a valid reason for going downtown in the morning, and while she was there she would visit the bookstore. That was what she had been waiting for all through Friday night, Saturday and Sunday—might as well admit it. She set down her empty cup and looked blindly out of the window.

She was setting out to look for a girl she had seen only once, a girl who had no reason to be interested in her; who might even, if they met again, actively dislike her. No reason she shouldn’t.

She put all the lists in her purse and picked her way back to bed. The radium dial of her clock said one twenty. She lay thinking about Erika’s greenish-gray eyes. Did they slant a little or didn’t they? Something gave her a slightly exotic look, piquant with that fair hair. She fell asleep trying to make up her mind.

Bill looked a little guilty at breakfast and a little resentful too, like a man who has been accused of something he didn’t do but would have liked to. He said, “It’s going to be a hot day,” and she said, scorning the weather, “I’m going downtown to look at some furniture. All right?”

“Better fix yourself some breakfast then.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“You don’t need to diet. You women are all crazy when it comes to weight.”

“That’s right.”

He looked at her, unsatisfied but finding nothing to argue with.

She put on an old cotton skirt, plain shirt and loafers, office clothes left over from the days when she was Bake’s girl—not to be confused with Mrs. William Ollenfield. Pushing the hangers along her closet bar and looking with distaste at her wardrobe, she wondered what had ever possessed her to buy so many clothes she didn’t like. Mrs. William Ollenfield seemed to be the sort of woman who goes shopping in a hat and gloves, who wears little printed silks and puts scatter pins on the lapel of a suit. Sooner or later, she would want and get a fur coat. Frances faced herself in the long mirror.

She was no longer certain who she was or what she might hope to become, but she certainly didn’t intend to spend the rest of her life pretending to be Mrs. William Ollenfield, that smug little housewife. She didn’t even like the way the woman did her hair. She ran a wet comb through the lacquered curls, smacked down the resulting fuzz with a brush dipped in Bill’s hair stuff, and caught the subdued ends in a barrette. The plain styling brought out the oval shape of her face and the winged eyebrows, her only beauty. (Not quite the only one, Bake had argued, touching her lightly to remind her.) Now she was beginning to look like herself again.

She ran downstairs, relishing the freedom of bare legs and old shapeless loafers.

It was one of those lazy summer days that seem endless, with sunlight clear and golden over the world and great patches of shade under arching branches. Grass and trees still wore the bright green of early summer. People moved along with open, friendly faces, looking washed and ironed. She climbed aboard a fat yellow bus and handed the driver a dollar, not wanting to admit that she didn’t know what the fare was. He gave back eighty-five cents.

She saw now that at some point during the weekend she had ceased to take for granted the continued backing of the Ollenfield income. She felt free and self-reliant. She wasn’t sure why, but no doubt she would find out in time.

In front of the bookstore, however, she lost her courage. She stood looking into the display window, which was just as it had been on Friday except for a small ivory Madonna where her wooden cat had been. As long as she didn’t go in, anything was possible. But if she went in and Vince wasn’t there, or if he was cool to her or refused to tell her about Erika—well, she reminded herself, I won’t be any worse off than I was this time last week. Back where I started from.

But she knew she would have lost something important. A hope so new and fragile she dared not examine it.

She turned the knob and went in.

The fair girl was sitting on a folding chair at the back of the room, writing on a clipboard. She looked up as Frances came in, heralded by the little silvery bell. Several expressions crossed her face—recognition, surprise, terror. She stood up, holding the clipboard stiffly at her side. “Vince. Customer.”

A voice from somewhere in the back. “Don’t forget what I said.”

“Vince says that I owe you an apology. I’m sorry I was rude.”

“But you weren’t rude. You were terribly polite.”

“That’s what Vince said. There is a rude kind of politeness.”

“I know, you use it on people you don’t like. But there’s no reason you should like me,” Frances admitted. “You don’t even know me. I have no business going around asking strangers out for drinks—”

“I keep telling her,” Vince said, coming in elegantly from a back room, dirty hands held out in front of him, “you either like people or you don’t, and why wait for a formal introduction? Personally,” he said airily, “I always know the first time I meet somebody, and I hardly ever change my mind. I must say this is an improvement over that terrible dress you had on the other time, though.”

Frances was too embarrassed to answer. Vince came to a graceful stop between her and Erika. “It’s my day for apologies too,” he said nicely. “I didn’t get your name and address when you were here, or ask you what kind of books you were interested in. You left your packages, too.”

“Frances Ollenfield.”

“This is Erika Frohmann. Now you’ve been introduced. You can be rude to each other if you want to.”

He retreated into the back again. There was the sound of running water. Erika Frohmann seemed to be gathering up her courage. “I’m not very good at meeting people,” she said, looking not at Frances but at the floor. “And you reminded me of someone too. Not a parent.”

“I look like a million other people.”

Vince emerged again, drying his hands on a small grimy towel. “Don’t be modest, my dear. You have a lovely profile—now you’ve done away with those dreadful, horrible curls. If I didn’t give my customers a little shove they might never get acquainted. They’re such a small group I feel they ought to know one another.”

Frances said, “I like small groups.” Take off your mask, let me see if you know. They wouldn’t, of course. Even if they wondered, caution was an hourly habit. She asked, hot faced, “Is it all right if I look at the books?”

“Sure, go ahead. You can wash your hands when you get through.”

Erika Frohmann said defensively, “Paper gets so dirty.” She sat down again, but tentatively, propping her clipboard against the edge of a counter and plainly trying to think of something to write. Her apology made and accepted, if only tacitly, the conversation was apparently over as far as she was concerned.

Frances walked slowly to the shelves, conscious of the silent figure behind her. But the fascination of print took over. Bake had long ago introduced her to secondhand bookstores on Clark Street and Dearborn, a wonderful clutter of junk and treasure, with the three-for-a-dollar bins just outside their doors and tables of old tattered paperbacks just inside. She was still unable to pass a secondhand bookstore.

This place was small, but there was enough to keep her here all day. She walked slowly, picking up volumes as she went along, now and then putting one back, scrupulously, where it had been in the first place.

Here were the Ann Bannon books side-by-side with Jeanette Foster’s Sex Variant Women in Literature, North Beach Girl, and Take Me Home next to the Covici-Friede edition of The Well of Loneliness, dated 1928. Here, huddled together as though for warmth in an unfriendly world, were Gore Vidal and a tall thin volume of Baudelaire, translated by someone she had never heard of. Here were books in the field, for people with a special interest, a special orientation.

Her voice came out shrill with self-consciousness. “Are these for sale?”

Vince came to see what she was talking about. “That depends. Why do you want them?”

Now. Tell him. But she could only say, “I’ve read most of them, but there are some I don’t know.”

He looked at her. The right answer evidently showed on her face; he nodded. “I’ll ask Erika. A lot of them belong to her. She may want them back.”

Erika stood up, soundless in flat canvas shoes. He said, indicating Frances with his thumb, “Can she have your books?”

“What for?”

“I thought you wanted to get rid of them. That was the general idea of bringing them here, wasn’t it?”

“But not to just anybody.”

Frances waited. The books are here to be sold, she thought, this is a bookstore. Why are they on display if they’re not for sale? But she said nothing. Something more was involved—this was a matter with deep emotional implications, and anything she said was likely to be wrong. It was the boy, Vince, who said with an impatient edge to his voice, “You can have them back if you’ve changed your mind. Go on, take them home with you.”

Erika’s face was hard and cold. She looked at Frances. “Let her take them if she wants. But not for money.”

“Look, we went through this with the insurance money.”

“It’s the same thing.”

Vince said to Frances, “It’s not just curiosity, is it? You won’t pass them around for your friends to laugh at?”

Frances said steadily, daring everything now, “If I had any friends here, they’d be interested for different reasons.”

Vince smiled. “Okay, they’re yours. No charge. Get them out of Erika’s way. She likes to come here and brood.”

Erika put the clipboard down on the counter, carefully, as though it might shatter. She walked soundlessly out of the store. The chimes over the door jingled. A streak of sunlight flashed across the floor and was gone.

Vince took the half dozen assorted books Frances was holding, since she seemed unable to put them down. “Don’t look that way. I wasn’t trying to hurt your feelings.”

“It’s her feelings.”

“Her best friend was killed. I told you.” The graceful shrug was as much a part of him as his clear brown eyes. “Girls are so sentimental. You have to go on living, and sooner or later you find someone else. It’s a little soon for her, that’s all.”

Frances said in a whisper, “I like her.”

“Sure. She’s had a bad time. She’s an Austrian, she was in a concentration camp when she was eleven, twelve years old, I don’t know exactly. Her whole family was murdered. I think it took all the courage she had to really love anyone—I think Kate was the only person she ever gave a damn about. If Kate had lived they would have stayed together forever like an old married couple. She’s a monogamous type,” Vince said, apparently not considering monogamy much of a virtue.

Frances opened one of the paperbacks to hide her confusion. The name, Kate Wood, was written strongly across the top of the title page in black ink. She said, “Some people would have kept these, and grieved over them.”

“Erika’s very strong. It would be better if she yelled and fainted,” Vince said sadly. “I love her. Not in an erotic way, of course.”

Frances said, “I think I could love her, period.”

“You’re gay.”

“Yes.”

“Doing anything about it?”

“Not right now.”

“You should never admit you’re gay,” Vince said quietly, “people have such fantastic ideas. You have to wear a disguise most of the time—if somebody finds out!” He drew a finger across his throat. “It’s worse for us, though.”

“I believe you.”

He lifted graceful shoulders. “So keep the books. Erika won’t take money for them. It’s a superstition, like the women who won’t cash their children’s insurance policies. We went through that, too. Kate had a group policy where she worked, made out to Erika as the beneficiary. Erika paid the funeral expenses out of it and gave the rest away. She’s terribly hard up, she never has any money, but that’s what she wanted to do.”

“I can see how she felt.”

“Yeah, but couldn’t she see that Kate wanted to leave her provided for? She hasn’t got a nickel saved. What happens if she gets sick and can’t work?”

I’d take care of her, Frances thought, warming. I’d work my hands off to take care of her.

“She gave away all Kate’s clothes and all the furniture and stuff they had and moved into a furnished room. I don’t know what it’s like, I’ve never been there. As far as I know nobody has. I’ve got a key, she gave it to me when she got out of the hospital—she was afraid of dying in her sleep,” Vince said matter-of-factly. “She was supposed to call me up every day, and if she missed a day I was supposed to check. But she never missed. You don’t just walk in on Erika.”

Frances wondered if it were a warning. She said, “I’ll take care of the books. Maybe she’ll want them back some time.”

“I don’t know why she didn’t keep them.”

Frances knew. Books have a life of their own. She felt warm and tender, as though she were melting with compassion. She said with some difficulty, “Tell her I took them, will you? And tell her—”

“With some things, you have to do your own telling.”

“Yes. Of course. Can I take some of these now and come back for the rest?”

“Any time, sure. Wash your hands before you go.”

Out in the street, she looked around with some surprise. For a while she had forgotten where she was—and who she was supposed to be. Maybe, she thought, I can start being myself again. She stood uncertainly in the middle of the sidewalk, holding the heavy package Vince had tied for her: ten, and she could pick up the rest a few at a time. She had a good reason to go back.

Furniture, she thought dimly, finding her crumpled lists as she hunted for tissues in her handbag. She didn’t want to shop. She wanted to go somewhere and think about Erika Frohmann. She wanted to talk to Kay, who was in Iran by this time and out of her reach since there are some things you can’t say in letters.

Vaguely, with nothing better to do, she made her way to Shapiro’s and roamed through the furniture department on the top floor, looking at things without seeing them, until her package became too heavy.

What difference did it make how she furnished the house? It wasn’t her house, never would be. She wasn’t going to stay in it. But she realized that she would have to account for the day to Bill.

She had forgotten Bill, too. For a couple of hours he had stopped existing.

She stood in front of a French Provincial chest, looking beyond it, holding her packet of books as though it were a child.