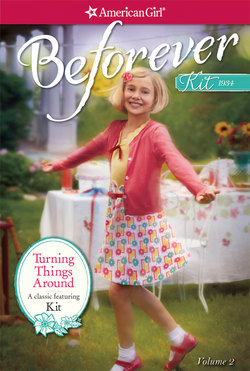

Читать книгу Turning Things Around - Valerie Tripp - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Waste-Not, Want-Not Almanac CHAPTER 2

Оглавлениеhe next day, Aunt Millie woke Kit early.

“Come with me,” she said.

“Now?” Kit asked groggily.

“Yes! Time to greet the ‘rosy-fingered dawn,’” Aunt Millie replied.

Kit swung out of bed and dressed as quickly as she could. Aunt Millie was not wearing the Sunday-best clothes she had worn for traveling the day before. Instead, she was wearing no-nonsense work clothes. Her old leather boots and straw hat had seen better days, and her sweater had mismatched buttons and tidy patches on the elbows. Over her faded, but very clean, flowered dress, she wore a starched and ironed all-over apron. She was holding two empty cloth sacks.

“What’re we doing?” Kit whispered as she tiptoed behind Aunt Millie.

“Collecting while the dew is fresh,” said Aunt Millie. When they were outside, Aunt Millie handed Kit one of the sacks. “We’re going to gather dandelion greens for salad,” she said.

“Dandelions?” squeaked Kit. “You mean we’re going to eat our lawn?”

Aunt Millie picked out a dandelion green and handed it to Kit. “Taste this,” she said.

Kit took a nibble. “Hey!” she said. “It’s good!”

“And free,” said Aunt Millie. “Let’s get to work.”

It was just like Aunt Millie to see the possibilities in a weed. No one in the world is better at making something out of nothing, Kit thought as she picked.

By the time everyone else was up, Aunt Millie and Kit had filled their sacks with dandelion greens and had also weeded most of the lawn while they were at it. Aunt Millie was a great one for being efficient. That very afternoon, Aunt Millie, Kit, Dad, and Charlie took hoes and shovels out of the garage and started to rip up a corner of the lawn to plant vegetables there.

“Wait!” cried Mother. “I like the idea of growing vegetables. But couldn’t we put the patch behind the garage, where people wouldn’t see it?”

“This is nice, flat land that gets plenty of sunshine,” said Aunt Millie positively. “Things’ll grow beautifully here. It’s too shady behind the garage.”

“I guess that makes sense,” said Mother.

Kit could tell that Mother was not pleased to have the lawn torn up right next to her azaleas. The plot for the vegetable garden was an unsightly mud patch. Kit herself was doubtful that the little seeds Aunt Millie had brought would amount to anything. The seeds were wrapped in twists of newspaper that Aunt Millie had labeled and packed carefully in an old cloth flour sack. As Kit planted the tiny gray seeds, she couldn’t believe they’d become big red tomatoes, orange carrots, green beans, or yellow squash. But Aunt Millie was cheerfully confident that time, sun, water, and hard work would bring about the magical transformation.

“How come you’re so sure?” Kit asked her.

Aunt Millie considered Kit’s question. “I guess teachers and gardeners are just naturally optimistic,” she said. “Can’t help it. Children and seeds are never disappointing.” She stood and brushed the dirt off her knees. “Save the flour sack,” she said. “I’ll make you a pair of bloomers out of it.”

“Bloomers?” laughed Kit. “Oh, Aunt Millie, you’re kidding! I couldn’t wear underwear made out of a flour sack, for heaven’s sake!”

“And why not?” Aunt Millie asked.

“Well,” Kit sputtered, “what if someone saw them? I’d be—”

“Waste not, want not, my girl,” said Aunt Millie tartly. Then, like the spring sun coming out from behind a cloud, she smiled. “You’ll like the bloomers,” she said. “You’ll be surprised.”

Kit soon learned that life with Aunt Millie around was full of surprises because Aunt Millie was full of ingenious ideas. She could find a use for anything, even things that were old and worn out. To Aunt Millie, nothing was beyond hope.

“There’s plenty of good left in these sheets,” she said when Kit showed her the ones that were thin in the middle. It was a few nights later. Everyone was gathered around the radio waiting for President Roosevelt, who was going to speak in what he called a “fireside chat.” Aunt Millie was a big fan of President Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor, and had asked Dad to move Mother’s sewing machine into the living room so that she could sew while she listened. She liked to do two things at once.

“Watch this, Margaret Mildred,” she said to Kit. As Kit watched, Aunt Millie tore the sheets in half, right down the middle. Then she sewed the outside edges together. “Now the worn parts are on the edges and the good parts are in the middle,” she said. “These sheets’ll last ten more years.”

The next night, Aunt Millie taught Kit how to take the collars and cuffs off Dad’s shirts and sew them back on reversed, so that the frayed part was hidden. Kit was pleased to know how to do something so useful. She was glad when Aunt Millie promised, “Tomorrow night I’ll teach you how to sew patches on so they don’t show.” And Kit was proud when, as everyone was saying good night, Aunt Millie announced, “If you’ve got anything that needs patching, bring it down tomorrow. Margaret Mildred and I’ll take care of it for you.”

Kit saw that Mother’s lips were thin as she tidied up the room. Kit was puzzled. Since Dad lost his job, no one had struggled harder than Mother to save money. Surely she appreciated all Aunt Millie’s frugal know-how! And yet it seemed that Mother felt the same way about the sewing machine in the living room as she’d felt about the vegetable patch in the yard. It was just too visible.

But Kit thought it was great fun to have Aunt Millie and the sewing machine right in the thick of things. The living room felt cheery and cozy in the evenings with the sewing machine clicking away while the boarders chatted or listened to the radio. Kit liked learning all of Aunt Millie’s skillful tricks, like how to use material from inside a pocket to lengthen pants, how to embroider yarn flowers over tears, holes, and stains, and how to darn socks so that they were as good as new. Aunt Millie was a good teacher. She was brisk and precise, but patient.

“I love the way Aunt Millie takes things that are ugly and used up and changes them into things that are beautiful and useful,” Kit said to Ruthie and Stirling as they walked home from school one day.

“Just like Cinderella’s fairy godmother,” said Ruthie, who liked fairy tales. “You know, how she turned Cinderella’s rags into a ball gown.”

“Aunt Millie uses hard work instead of a wand,” said Kit. “But it does seem like she can do magic.”

“Maybe you should show her the picture of the Robin Hood party,” said Ruthie. “Maybe she could figure out a way to do that.”

“I don’t think so,” sighed Kit. “But she sure has lots of great ideas.” Suddenly Kit had a great idea of her own. “You know what we can do?” she said excitedly. “We can write down Aunt Millie’s ideas. We’ll make a book! Ruthie, you and I can write it, and Stirling can draw the pictures.”

“What’ll we call it?” asked Ruthie.

“Aunt Millie’s Waste-Not, Want-Not Almanac,” Kit said with a grin. “What else? The thing Aunt Millie hates most is waste, and it would be a terrible waste if we forgot all she’s taught us after she leaves. Writing her ideas down will be a way of saving them. We won’t tell Aunt Millie about our book. Then right before she goes home, we’ll show her. It’ll be a way to thank her.”

“Is she leaving soon?” asked Stirling.

“I hope not!” said Kit. “Come on, let’s run home and get started before I have to do my chores!”

Kit didn’t have a blank book, so she took one of Charlie’s old composition books, turned it upside down, and wrote on the unused back sides of the pages. She divided Aunt Millie’s Waste-Not, Want-Not Almanac into four sections: “Growing,” “Sewing,” “Cooking,” and “Miscellaneous Savings.” In the “Growing” section, Stirling drew a sketch of the vegetable patch. Ruthie labeled the rows, and Kit wrote Aunt Millie’s advice about planting, watering, and weeding in the margins. In the “Sewing” section, Stirling drew diagrams to show how to turn sheets sides-to-middle and how to reverse cuffs. Kit wrote out the directions in easy-to-follow steps.

Almost every day there was something new to add to the Almanac. Aunt Millie taught the children how to trace a shoe on a piece of cardboard, cut it out, and put the cardboard in the shoe to cover up a hole in the bottom. She showed them how to take slivers of soap, melt them together, and mold them into new bars of soap. She also taught the children to save string, basting thread, and buttons, and to be on the lookout for glass bottles to return for the deposit.

One day, when Kit and Stirling came home from school, they saw a horse-drawn wagon parked in front of the house. It belonged to the ragman, who paid by the pound for cloth rags. Kit had always wanted to get to know the ragman’s horse, but Mother never asked the ragman to stop. She said the horse was unsanitary. Aunt Millie, however, was petting the horse and feeding it apple cores. Kit and Stirling were tickled when Aunt Millie let them feed the horse, too.

“‘My kingdom for a horse,’” said Aunt Millie, quoting Shakespeare as she petted the horse’s nose. She smiled at the ragman. “If I’d known you were coming, I’d have gathered up some rags to sell you. We have some dandies.”

The ragman was very pleased by Aunt Millie’s kindness to his horse. “I’ll tell you what,” he said. “I wasn’t planning to come back this way next week, but for you, I will.”

Kit and Stirling exchanged a glance. Here was a typical Aunt Millie idea to put in their Almanac: save apple cores, charm the ragman, and get good money for your rags!

Saturday rolled around, and Kit was delighted when Aunt Millie announced that she and Kit would do the grocery shopping. They set forth after Kit had washed and ironed all the sheets and remade all the beds. Aunt Millie had her hat firmly fixed on her head and her shopping list, written on the back of an old envelope, firmly held in her hand. Kit skipped along next to Aunt Millie, eager and alert. She was sure to hear more good ideas for the Almanac on this shopping trip. Kit had noticed before that when she was writing about something, she had to be especially observant. Writers had to pay attention. Everything mattered.

Kit’s heart sank a little when she saw that they were headed to the butcher shop. The butcher was well known to be a stingy grouch.

“What would you like today?” he asked Kit and Aunt Millie.

Aunt Millie spoke with more of a twang than usual. “I’d like,” she said, “to know what an old Kentucky hilljack like you is doing in Cincinnati.”

Kit gasped. She was sure the butcher would be angry. It was not complimentary to call someone a “hilljack.” But Aunt Millie’s question seemed to have worked another one of her magical transformations.

Smiling, the butcher asked, “How’d you know I’m from Kentucky?”

“Because your accent’s the same as mine,” said Aunt Millie.

The butcher laughed. For a long while, he and Aunt Millie chatted and swapped jokes as if they were old friends.

“Now,” Aunt Millie said at last, “if you’ve got a soup bone and some meat scraps you could let me have for a nickel, I’ll make some of my famous soup.” She pointed to Kit. “And Margaret Mildred here will bring you a portion. How’s that?”

“It’s a deal,” said the butcher cheerfully.

As they left the butcher shop, Kit hefted the heavy parcel of meat. “Gosh, Aunt Millie,” she said. “All this for a nickel?”

“A nickel and some friendliness,” Aunt Millie said. “Works every time.” She caught Kit’s arm. “Slow down there, child. What’s your hurry?”

“Well,” said Kit, “you and the butcher talked so long, I’m afraid the grocery store will be closing when we get there.”

Aunt Millie winked. “I hope so,” she said.

Kit was confused until Aunt Millie explained, “Tomorrow’s Sunday and the store’ll be closed. So, just before closing time today, the grocer will lower the prices on things that’ll go bad by Monday.”

“Ah! I see!” said Kit.

Of course, Aunt Millie was right. The grocer was lowering the prices. Aunt Millie and Kit were able to get wonderful bargains on vegetables close to wilting, fruit that was at its ripest, and bread about to go stale. Aunt Millie bought a whole bag of day-old rolls, jelly buns, and doughnuts for a dime, a loaf of crushed bread and a box of broken cookies for a nickel each, two dented cans of peaches for six cents, and a huge bag of bruised apples for a quarter.

Kit was impressed by Aunt Millie’s money-saving cleverness. Yet for some reason, Kit squirmed. Everyone in this store must know my family’s too poor to pay full prices, she thought. Aunt Millie counted every penny of her change. When the grocer sighed impatiently and the people waiting in line craned their heads around to see what was taking so long, Kit went hot with self-consciousness.

As they walked home, Aunt Millie said, “You’re very quiet, Margaret Mildred. Where’s what Shakespeare would call my ‘merry lark’?”

Kit spoke slowly. “Aunt Millie,” she said, “do you ever feel funny about…you know…having to buy crushed bread and broken cookies and all?”

“Everything we bought’s perfectly good,” said Aunt Millie. “It may not look perfect, but none of it’s rotten or spoiled. It’ll taste fine, you’ll see.”

“I meant,” Kit faltered, “it’s…hard to be poor in front of people.”

“Being poor is nothing to be ashamed of,” said Aunt Millie stoutly, “especially these days, with so many folks in the same boat.”

Kit shook herself. How silly she was being! Of course Aunt Millie was right. Kit knew she should be proud of Aunt Millie’s thrifty ideas. Wasn’t that the whole point of the Almanac? Kit turned her thoughts to her book. Which section should I put these new grocery shopping ideas in? she wondered. “Cooking” or “Miscellaneous Savings”?