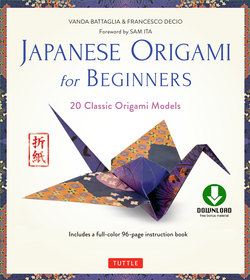

Читать книгу Japanese Origami for Beginners Kit Ebook - Vanda Battaglia - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

I grew up in a rural area of the United States. There was no Japanese community. When I was four or five years old, my grandmother sent care packages from Seattle to my family, containing items such as soy sauce, dried miso, mushrooms, and various pickled vegetables or plums. Sometimes these packages would include a pack of origami paper. They always gave instructions for the same half dozen traditional models. We also had a fairly basic book of origami birds. At the time, I found some of these models very difficult and confusing. Others, easy enough, yet the finished product was unsatisfying. A few seemed to have a magical quality. The resulting object was greater than the sum of its folds. I practiced these models over and over, until I understood their logic, and could recreate them from memory with my eyes closed—often from school paper.

As an adolescent, I did very little origami. As an adult, sometimes I’d buy an origami book in an airport book store or a gift shop. I’d try folding a model or two from it. While I had neglected it, origami was growing at a tremendous pace! Perhaps, because I began folding at such an early age, I had never considered the creative aspects of origami. Each model I had casually folded was the result of someone else’s experimentation, decisions, and careful documentation.

I joined a folding group. We meet periodically at coffee shops in New York to talk origami, and fold. We fold everything; modulars, tessellations, animals, objects, furniture, etc.—often until the place closes. Some of my origami friends began folding from diagrams as children, just as I did, except they never stopped. They travel around the world attending origami conventions, inventing, and contributing models to publications. My newfound awareness of this expansive world of origami gives me an even greater appreciation for some of the traditional Japanese models, which undeniably inform and inspire their beautiful work.

Occasionally, I am invited to teach origami to groups of people. Whether they are graduate students at elite universities, or young children in a community center, they all seem to progress through similar degrees of frustration, determination, satisfaction, and delight. Some of the traditional models still popular around the world today were only transmitted through oral traditions for hundreds of years. Perhaps, origami holds the key to some sort of universal creative potential.

I am asked at times if making pop-up books, my occupation, is related to origami. My answer is yes. While on the surface, they both involve folding paper; on a deeper level, I believe origami holds relevance to all artists. Perhaps my experience of learning traditional models as a young child helped me take to paper engineering early in my career. As pop-up books have become more and more sophisticated, there is always the temptation to try forcing paper to my will. More often than not, I find the paper will rebel, and produce results that are cluttered, frivolous, or not properly functional. Traditional origami serves as a reminder of efficiency and elegance, using the properties of the paper to express the model. I’ve heard that Michelangelo described sculpting as a process of freeing the model from a block of marble. Similarly, Yoshizawa spoke of the process of folding origami as an embryo developing, maturing, and emerging. I still find that folding paper relaxes the mind, and nurtures the soul.

This book contains a great deal of information, and some of the most important Japanese traditional models. Whether it is your introduction to origami, or you are already well along on your journey, I hope you will be inspired by its contents. Happy folding.

Sam Ita

www.samita.us