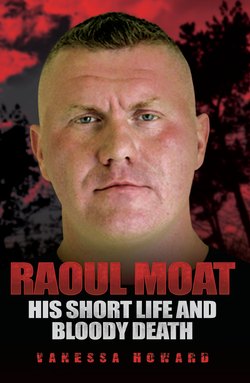

Читать книгу Raoul Moat - Vanessa Howard - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1973

ОглавлениеNewcastle’s West End has known its share of problems. The city as a whole has been in an inexorable economic decline for decades, ever since the collapse of the heavy industries that forged so much of its identity, a proud heritage based on shipping, steel and coal.

There have of course been any number of initiatives to try and halt the decline and rebuild its economy and, as with much of the rest of the country, employment, where it has been created has been in the retail and service sectors. It’s a far cry from its male-dominated blue-collar past, but times change and communities have to find a way to adapt.

The West End is called that because of its geography alone, standing as it does to the west of the city centre and stretching for about four miles to the A1. In many ways it is unremarkable: outlying towns were gradually absorbed by the city as it grew rapidly during the Industrial Revolution and now its residential streets look like many others, dominated by pre-war terraces and social housing built after the bombs stopped falling.

By the 1970s, the West End was at a crossroads although its residents were perhaps unaware of the drastic changes these would bring to the area. It was the start of de-industrialisation, the Vickers plant at Scotswood closed down and was followed by that of Elswick. The economic base that had underpinned the community was disappearing. With Vickers gone, others began to fail – engineering companies, components factories and metal spinners. The firms that provided decent wages and apprenticeships closed and nothing comparable was to take their place. Even when BAE systems opened a new plant in the 1980s, it employed 450 at its Scotswood site, compared to the 25,000 that had been working there at its height. It was truly the end of an era.

Unemployment numbers rose sharply, as did deprivation, and many people began to move out of the area, leaving houses unsold and boarded up. A great many of the ‘slum terraces’ had been demolished in the 1960s, and in the 1970s council estates took their place. Despite a number of initiatives, both on a large and small scale, none had any serious impact on the levels of poverty in the West End.

It was an area in decline. Population fell as those who could leave moved away and for those who stayed, ill-health was rife, educational attainment was poor, and jobs were scarce. It was into this declining community that Raoul Thomas Moat was born. This was not his mother, Josephine’s, first child – she had already given birth to a son three years earlier. She named her first-born Angus, but was not in contact with his father or the father of her newborn second son.

Raoul is not a common first name but Josephine was not deterred by the locality’s somewhat unimaginative expectations. Her family weren’t originally from the West End and her maternal ancestors had once made their fortune in commerce. Much of that was a memory by the time Josephine’s mother Margaret came to marry Thomas Moat. Raoul’s mother was the youngest of three daughters and, like many young women growing up in the 1960s, she had adopted a much less constrained outlook on what she could do with her life in comparison with her mother’s generation.

Josephine sought work as a draughtswoman, creating detailed technical drawings, something again which marked her out as different from many of her contemporaries: women who took part-time or unskilled jobs in order to work around their commitments as wives and mothers first, and wage earners second.

When Josephine was due to give birth to Angus in 1970, she was living with her parents. Neither they nor her sisters knew who the child’s father was and she made the firm decision not to tell them. She was no longer a child, she was in her early twenties, and so there was little the family could do but accept her decision and support her as best they could.

Being a lone parent in 1970 carried a good deal more of a social stigma than it does today, only 40 years later. The word ‘bastard’ was a very hurtful insult for any child to have to bear but Josephine was undeterred and prepared to continue to work and to carry on with her life.

Some may have viewed this as a bold decision but, on the whole, this was a community that had many other concerns to preoccupy it. The West End was becoming notorious. Much of its ‘lawless’ reputation was an exaggeration but its rundown appearance, its empty and derelict houses, and abandoned industrial wastelands did little to alter perceptions. And besides, there were some episodes in its recent past that would forever associate the area with the worst of human tragedies.

Just two years before Angus was born, Mary Bell was arrested and later convicted for the manslaughter of two boys, four-year-old Martin Brown and three-year-old Brian Howe. Mary had grown up in and around the streets of Scotswood. Her mother was a prostitute and Mary had been severely abused, she would later claim, by both her mother and her mother’s clients. She did not know who her father was and by the age of ten, she was a traumatised and troubled girl and it was the expression of her disturbed state of mind that would bring terrible consequences.

It was the day before Mary’s eleventh birthday, 25 May 1968, when she found four-year-old Martin out playing. It wasn’t until later that afternoon that his body was found in a boarded-up house by three other boys out looking for scraps to salvage. At the time, Martin’s death was viewed as a possible accident and an open verdict was returned, but local residents were distraught and demanded that something should be done about the dangerous and derelict houses in the area. Indications that the young boy had been strangled were missed.

Just two months later, Mary and a friend Norma, an older girl but one very much in Mary’s thrall, lured three-year-old Brian Howe onto some waste ground. Norma later confessed that she saw Mary asphyxiate Brian and that her attempts to pull Mary off the boy failed. She later returned with Mary to where Brian’s body was hidden. Mary had brought with her a pair of scissors and a razor blade. The eleven-year-old carved the letter ‘M’ onto Brian’s stomach and cut away some of his hair.

A month later the police had linked the two murders and the two girls were taken away to the West End police station and the trial was held in December of that year. Norma was acquitted but Mary was convicted and sentenced to an indefinite sentence of imprisonment. She was eventually released in 1980 and her story hit the headlines once more when she collaborated on producing a book with the writer Gitta Sereny, a journalist who had covered the original trial.

In Cries Unheard, Bell revisited her childhood trauma and attempted to understand what drove her to do such appalling acts. One of the most revealing moments came when she described what she felt when she strangled another child:

‘I’m not angry. It isn’t a feeling… it is a void that comes… it’s an abyss… it’s beyond rage, beyond pain, it’s a draining of feeling.’

This chilling absence of feeling, a release from feeling in fact, is characteristic of abused children who grow up to become abusers. Children who have suffered are at risk of maturing into young adults who find release only when inflicting pain on others.

At the time of Mary Bell’s conviction she was described as displaying signs of psychopathology. To the residents of the West End she was seen as a monster. ‘Mary Bell, Mary Bell, there’s a place for you in hell’, became a childhood rhyme and her name became a byword for something evil, something that could stalk and prey on children, a figure in the shadows like any other bogeyman.

Raoul Moat would have come to know the name – every child in the area did. There were some who believed she was born evil but as time moved on, more who wondered how much her environment shaped her, and in particular, the destructive role played by her mother, Betty Bell.

Neglect in childhood can have devastating consequences on the way a child develops, particularly the child’s ability to form emotional bonds and show empathy for others. It is an issue that goes far beyond failing to provide food or clothing, it also encompasses the impact of emotional neglect.

Very often, if a primary carer is unable to provide loving and consistent emotional care for a child, the damage can be far reaching. It may be a temporary state such as postnatal depression and therefore can be overcome, and long-term difficulties can be avoided. But if a primary carer has an ongoing mental illness, the obstacles can be far harder to navigate, as Josephine’s sons were to find.

Raoul’s mother’s surviving son, Angus, has spoken to the press of the difficulties he faced growing up. He has characterised his mother as someone who failed him and his brother. He said: ‘Our mother was selfish. Without getting all dewy-eyed about it, we had a terrible childhood. My mother is not a very nice person.’

Every unhappy family is beset with anger and accusation and it is impossible to ever find the truth of what has gone on behind closed doors. No two accounts of what happened will match up and as time moves on, the past becomes ever more distorted by memory and regret. What is known is that Raoul and his brother were in large part raised by their maternal grandmother. Angus has said that his mother’s presence was erratic and that she was absent for periods of time, although he accepts that her diagnosis as someone who was suffering with a bipolar disorder accounted for her spells in hospital.

Bipolar disorder, once known as manic depression, can be a challenge for any family. Children can witness a parent stare absently in a trance-like state for hours, or find them possessed by excessive energy, making plans that are hopelessly impractical and even running up serious debt as they pursue them. Not knowing what state a parent will be in each day, whether high and excitable or low and depressed, can cause stress and ongoing upset in a child. The youngster then might blame him or herself for the illness and internalise a lot of anguish, and the impossibility of distracting their parent and gaining much needed attention, can be the root of additional problems.

Not all children with a bipolar parent suffer, but many do. Looking at the bright and bonny pictures of Raoul as a baby, it is easy to imagine that he was a boy with everything to look forward to. But Angus has spoken of the difficulties his younger brother faced, saying: ‘My mum was absent a lot of the time in mental hospitals. And often at home she was knocked out on medication. So you basically got a zombie or an absent mother.

‘It’s not a good position to be in. My grandma had to be there for us – and she was. She did a very good job.’

Having a stable and consistent influence in the life of any child that has an absent parent is essential if a young person is to thrive, but even with his grandmother’s steady influence Angus has said that he struggled, particular with anger. He said: ‘Yeah, it made me angry. I’m always angry. I’m still angry. Just not as angry as Raoul.’

How boys learn to mitigate their anger has been the subject of a number of studies and the impact of parenting in the early-years cannot be overlooked. It is believed that if boys do not receive enough consistent care and attention that the areas of the brain that process empathy and self-control can be damaged. It can affect the amygdalae, the part of the brain that processes memories that are connected to emotional events; and if the child has not learned that their needs are met, it can lead to an oversensitive reaction to stress.

Emotional neglect has also been linked to the fall in the production of the hormone serotonin that induces calm, whilst the production of corticosterone, the stress hormone, is increased. Taking all these factors into account, neglect in the early years can mean that some boys find it harder to develop empathy and have less control over their violent impulses when they encounter stress.

The plump baby smiling out in the Moat family album would grow up to find that his mother could not always provide him with the care he wanted and he would enter school knowing that he was one of the very few who did not have a father.

Angus helped. Being three years older, he was someone Raoul looked up to and would follow around his grandmother’s house, and, unlike many brothers, Angus was happy to spend time with his young brother and the two quickly became inseparable. They looked different: perhaps not surprisingly, Angus had brown locks like his mother whilst Raoul had a shock of red hair. Physically the one thing they shared was their eye colour – both had bright blue eyes.

From the very start, as soon as he was able to, Raoul liked to spend time outside. He was at his happiest in the garden, looking under stones to find bugs, and he’d watch with fascination as insects and spiders crawled around. Sometimes he would even put them in his pocket, as if to keep them for later inspection. He was gentle, an inquisitive soul.

Come washing day, it wasn’t uncommon to find Raoul’s pockets filled with stones, leaves and anything else that caught his eye as he explored the garden. In that way, he was just like any other boy and yet his grandmother Margaret knew that when it was time to start school, he would not be regarded and accepted in the same way as the other boys would.

There was his name for a start. Raoul is uncommon now and was virtually unheard of in the mid 1970s. It is a French version of the name Ralph and its roots are in Old Norse, meaning ‘wolf counsel’. Josephine would hint at one stage to her youngest son that his father was French but it isn’t possible to know if this was true or not. As it stood, no one would know how to spell his name and many would struggle with its pronunciation. Having an unusual first name is increasingly fashionable today, but 30 years ago it was more likely to guarantee that other children would find it something to mock rather than admire.

Angus was a name that wasn’t common but at least it was recognisably Scottish and a great many people on Tyneside have Scottish ancestry. Yet even Angus found that his name would be played on and ‘Angry Angus’ and ‘Anguish’ would become two of the nicknames he’d become known by.

Anger. Even from the start it seemed that the two Moat boys would not be able to escape the effects of anger. Anger at an absent mother, anger at the void she left by not allowing them to know who their fathers were, anger that their ageing grandmother was the only consistent presence in their lives, and anger that others knew as much about their history as they did.

It is hard to keep any secrets in a tightknit community such as that of the West End. This may have been a community suffering economically and socially but that did not stem the persistent and ever-present interest that everyone had in everyone else’s business; in fact, as family units started to break down and broken homes and absent fathers became more common, it could even intensify it. In Raoul’s family there was a ‘mad’ mother and two ‘bastard’ boys.

Margaret would lie awake at night and wonder what would happen to her two beloved grandsons. Her boys were always together and in a favourite image, Raoul’s first school photograph, they sat shoulder-to-shoulder with beaming smiles. She prayed that all her affection and care would be enough, that it would anchor them both. They’d had a tough start it was true but then so do many people who subsequently turn out perfectly all right.

Margaret had little idea of what lay ahead, of what would come to pass that would mean that two once inseparable brothers would spiral away from one another and onto very different paths.