Читать книгу Laura - Vera Caspary - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

When, at precisely twelve minutes past four by the ormolu clock on my mantel, the telephone interrupted, I was deep in the Sunday papers. Laura had become a Manhattan legend. Scarlet-minded headline artists had named her tragedy The Bachelor Girl Murder and one example of Sunday edition belles-lettres was tantalizingly titled Seek Romeo in East Side Love-Killing. By the necromancy of modern journalism, a gracious young woman had been transformed into a dangerous siren who practiced her wiles in that fascinating neighborhood where Park Avenue meets Bohemia. Her generous way of life had become an uninterrupted orgy of drunkenness, lust, and deceit, as titillating to the masses as it was profitable to the publishers. At this very hour, I reflected as I lumbered to the telephone, men were bandying her name in pool parlors and women shouting her secrets from tenement windows.

I heard Mark McPherson’s voice on the wire. “Mr. Lydecker, I was just wondering if you could help me. There are several questions I’d like to ask you.”

“And what of the baseball game?” I inquired.

Self-conscious laughter vibrated the diaphragm and tickled my ear. “It was too late. I’d have missed the first couple of innings. Can you come over?”

“Where?”

“The apartment. Miss Hunt’s place.”

“I don’t want to come up there. It’s cruel of you to ask me.”

“Sorry,” he said after a moment of cold silence. “Perhaps Shelby Carpenter can help me. I’ll try to get in touch with him.”

“Never mind. I’ll come.”

Ten minutes later I stood beside him in the bay window of Laura’s living room. East Sixty-Second Street had yielded to the spirit of carnival. Popcorn vendors and pushcart peddlers, sensing the profit in disaster, offered ice-cream sandwiches, pickles, and nickel franks to buzzards who battened on excitement. Sunday’s sweethearts had deserted the green pastures of Central Park to stroll arm-in-arm past her house, gaping at daisies which had been watered by the hands of a murder victim. Fathers pushed perambulators and mothers scolded the brats who tortured the cops who guarded the door of a house in which a bachelor girl had been slain.

“Coney Island moved to the Platinum Belt,” I observed.

Mark nodded. “Murder is the city’s best free entertainment. I hope it doesn’t bother you, Mr. Lydecker.”

“Quite the contrary. It’s the odor of tuberoses and the timbre of organ music that depress me. Public festivity gives death a classic importance. No one would have enjoyed the spectacle more than Laura.”

He sighed.

“If she were here now, she’d open the windows, pluck daisies out of her window-boxes and strew the sidewalks. Then she’d send me down the stairs for a penny pickle.”

Mark plucked a daisy and tore off the petals.

“Laura loved dancing in the streets. She gave dollar bills to organ-grinders.”

He shook his head. “You’d never think it, judging from the neighborhood.”

“She also had a taste for privacy.”

The house was one of a row of converted mansions, preserved in such fashion that Victorian architecture sacrificed none of its substantial elegance to twentieth-century chic. High stoops had given way to lacquered doors three steps down; scrofulous daisies and rachitic geraniums bloomed in extraordinarily bright blue and green window-boxes; rents were exorbitant. Laura had lived here, she told me, because she enjoyed snubbing Park Avenue’s pretentious foyers. After a trying day in the office, she could neither face a superman in gilt braid nor discuss the weather with politely indifferent elevator boys. She had enjoyed opening the street door with a key and climbing the stairs to her remodeled third floor. It was this taste for privacy that led to her death, for there had been no one to ask at the door if Miss Hunt expected a visitor on the night the murderer came.

“The doorbell rang,” Mark announced suddenly.

“What?”

“That’s how it must have happened. The doorbell rang. She was in the bedroom without clothes on. By the time she’d put on that silk thing and her slippers, he’d probably rung a second time. She went to the door and as she opened it, the shot was fired!”

“How do you know all this?” I demanded.

“She fell backward. The body lay there.”

We both stared at the bare, polished floor. He had seen the body, the pale blue garment blood-stained and the blood running in rivulets to the edge of the green carpet.

“The door downstairs had evidently been left unlocked. It was unlocked when Bessie came to work yesterday morning. Before she came upstairs, Bessie looked for the superintendent to bawl him out for his carelessness, but he’d taken his family down to Manhattan Beach for the week-end. The tenants of the first and second floors are away for the summer and there was no one else in the house. The houses on both sides are empty, too, at this time of year.”

“Probably the murderer thought of that,” I observed.

“The door might have been left open for him. She might have been expecting a caller.”

“Do you think so?”

“You knew her, Mr. Lydecker. Tell me, what kind of dame was she anyway?”

“She was not the sort of woman you call a dame,” I retorted.

“Okay. But what was she like?”

“Look at this room. Does it reveal nothing of the person who planned and decorated it? Does it contain, for your eyes, the vulgar memories of a young woman who would lie to her fiancé, deceive her oldest friend, and sneak off to a rendezvous with a murderer?”

I awaited his answer like a touchy Jehovah. If he failed to appreciate the quality of a woman who had adorned this room, I should know that his interest in literature was but the priggish aspiration of a seeker after self-improvement, his sensitivity no more than proletarian prudery. For me the room still shone with Laura’s luster. Perhaps it was in the crowding memories of firelit conversations, of laughing dinners at the candle-bright refectory table, of midnight confidences fattened by spicy snacks and endless cups of steaming coffee. But even as it stood for him, mysterious and bare of memory, it must have represented, in the deepest sense of the words, a living room.

For answer he chose the long green chair, stretched his legs on the ottoman, and pulled out his pipe. His eyes traveled from the black marble fireplace in which the logs were piled, ready for the first cool evening, to softly faded chintz whose deep folds shut out the glare of the hot twilight.

After a time he burst out: “I wish to Christ my sister could see this place. Since she married and went to live in Kew Gardens, she won’t have kitchen matches in the parlor. This place has—” he hesitated “—it’s very comfortable.”

I think the word in his mind had been class, but he kept it from me, knowing that intellectual snobbism is nourished by such trivial crudities. His attention wandered to the bookshelves.

“She had a lot of books. Did she ever read them?”

“What do you think?”

He shrugged. “You never know about women.”

“Don’t tell me you’re a misogynist.”

He clamped his teeth hard upon his pipestem and glanced at me with an air of urchin defiance.

“Come, now, what of the girlfriend?” I pleaded.

He answered dryly: “I’ve had plenty in my life. I’m no angel.”

“Ever loved one?”

“A doll in Washington Heights got a fox fur out of me. And I’m a Scotchman, Mr. Lydecker. So make what you want of it.”

“Ever know one who wasn’t a doll? Or a dame?”

He went to the bookshelves. While he talked, his hands and eyes were concerned with a certain small volume bound in red morocco. “Sometimes I used to take my sisters’ girl friends out. They never talked about anything except going steady and getting married. Always wanted to take you past furniture stores to show you the parlor suites. One of them almost hooked me.”

“And what saved you?”

“Mattie Grayson’s machine gun. You were right. It was no tragedy.”

“Didn’t she wait?”

“Hell, yes. The day they discharged me, there she was at the hospital door. Full of love and plans; her old man had plenty of dough, owned a fish store, and was ready to furnish the flat, first payment down. I was still using crutches so I told her I wouldn’t let her sacrifice herself.” He laughed aloud. “After the months I’d put in reading and thinking, I couldn’t go for a parlor suite. She’s married now, got a couple of kids, lives in Jersey.”

“Never read any books, eh?”

“Oh, she’s probably bought a couple of sets for the bookcase. Keeps them dusted and never reads them.”

He snapped the cover on the red morocco volume. The shrill blast of the popcorn whistle insulted our ears and the voices of children rose to remind us of the carnival of death in the street below. Bessie Clary, Laura’s maid, had told the police that her first glimpse of the body had been a distorted reflection in the mercury-glass globe on Laura’s mantel. That tarnished bubble caught and held our eyes, and we saw in it fleetingly, as in a crystal ball, a vision of the inert body in the blue robe, dark blood matted in the dark hair.

“What did you want to ask me, McPherson? Why did you bring me up here?”

His face had the watchfulness that comes after generations to a conquered people. The Avenger, when he comes, will wear that proud, guarded look. For a moment I glimpsed enmity. My fingers beat a tattoo on the arm of my chair. Strangely, the padded rhythms seemed to reach him, for he turned, staring as if my face were a memory from some fugitive reverie. Another thirty seconds had passed, I dare say, before he took from her desk a spherical object covered in soiled leather.

“What’s this, Mr. Lydecker?”

“Surely a man of your sporting tastes is familiar with that ecstatic toy, McPherson.”

“But why did she keep a baseball on her desk?” He emphasized the pronoun. She had begun to live. Then examining the tattered leather and loosened bindings, he asked, “Has she had it since ’38?”

“I’m sure I didn’t notice the precise date when this object d’art was introduced into the household.”

“It’s autographed by Cookie Lavagetto. That was his big year. Was she a Dodgers fan?”

“There were many facets to her character.”

“Was Shelby a fan, too?”

“Will the answer to that question help you solve the murder, my dear fellow?”

He set the baseball down so that it should lie precisely where Laura had left it. “I just wanted to know. If it bothers you to answer the question, Mr. Lydecker . . .”

“There’s no reason to get sullen about it,” I snapped. “As a matter of fact, Shelby wasn’t a fan. He preferred . . . why do I speak of him in the past tense? He prefers the more aristocratic sports, tennis, riding, hunting, you know.”

“Yep,” he said.

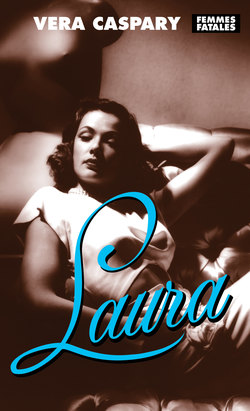

Near the door, a few feet from the spot where the body had fallen, hung Stuart Jacoby’s portrait of Laura. Jacoby, one of the imitators of Eugene Speicher, had produced a flattened version of a face that was anything but flat. The best feature of the painting, as they had been her best feature, were the eyes. The oblique tendency, emphasized by the sharp tilt of dark brows, gave her face that shy, fawn-like quality which had so enchanted me the day I opened the door to a slender child who had asked me to endorse a fountain pen. Jacoby had caught the fluid sense of restlessness in the position of her body, perched on the arm of a chair, a pair of yellow gloves in one hand, a green hunter’s hat in the other. The portrait was a trifle unreal, however, a trifle studied, too much Jacoby and not enough Laura.

“She wasn’t a bad-looking da—” He hesitated, smiled ruefully, “—girl, was she, Mr. Lydecker?”

“That’s a sentimental portrait. Jacoby was in love with her at the time.”

“She had a lot of men in love with her, didn’t she?”

“She was a very kind woman. Kind and generous.”

“That’s not what men fall for.”

“She had delicacy. If she was aware of a man’s shortcomings, she never showed it.”

“Full of bull?”

“No, extremely honest. Her flattery was never shallow. She found the real qualities and made them important. Surface faults and affections fell away like false friends at the approach of adversity.”

He studied the portrait. “Why didn’t she get married, then? Earlier, I mean?”

“She was disappointed when she was very young.”

“Most people are disappointed when they’re young. That doesn’t keep them from finding someone else. Particularly women.”

“She wasn’t like your erstwhile fiancé, McPherson. Laura had no need for a parlor suite. Marriage wasn’t her career. She had her career, she made plenty of money, and there were always men to squire and admire her. Marriage could give her only one sort of completion, and she was keeping herself for that.”

“Keeping herself busy,” he added dryly.

“Would you have prescribed a nunnery for a woman of her temperament? She had a man’s job and a man’s worries. Knitting wasn’t one of her talents. Who are you to judge her?”

“Keep your shirt on,” Mark said. “I didn’t make any comments.”

I had gone to the bookshelves and removed the volume to which he had given such careful scrutiny. He gave no sign that he had noticed, but fixed his fury upon an enlarged snapshot of Shelby looking uncommonly handsome in tennis flannels.

Dusk had descended. I switched on the lamp. In that swift transition from dusk to illumination, I caught a glimpse of darker, more impenetrable mystery. Here was no simple Police Department investigation. In such inconsistent trifles as an ancient baseball, a worn Gulliver, a treasured snapshot, he sought clues, not to the passing riddle of a murder, but to the eternally enigmatic nature of woman. This was a search no man could make with his eyes alone; the heart must also be engaged. He, stern fellow, would have been the first to deny such implications, but I, through these prognostic lenses, perceived the true cause of his resentment against Shelby. His private enigma, so much deeper than the professional solution of the crime, concerned the answer to a question which has ever baffled the lover, “What did she see in that other fellow?” As he glowered at the snapshot I knew that he was pondering on the quality of Laura’s affection for Shelby, wondering whether a woman of her sensitivity and intelligence could be satisfied merely with the perfect mould of a man.

“Too late, my friend,” I said jocosely. “The final suitor has rung her doorbell.”

With a gesture whose fierceness betrayed the zeal with which his heart was guarded, he snatched up some odds and ends piled on Laura’s desk, her address and engagement book, letters and bills bound by a rubber band, unopened bank statements, checkbooks, and old diary, and a photograph album.

“Come on,” he snapped. “I’m hungry. Let’s get out of this dump.”