Читать книгу The Story of Kullervo - Verlyn Flieger - Страница 8

ОглавлениеThe Story of Honto Taltewenlen

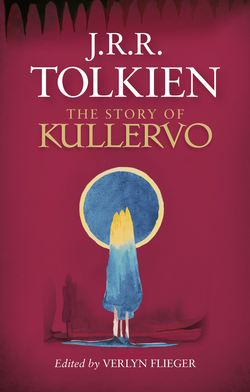

The Story of Kullervo

(Kalervonpoika)

In the days {of magic long ago} {when magic was yet new}, a swan nurtured her brood of cygnets by the banks of a smooth river in the reedy marshland of Sutse. One day as she was sailing among the sedge-fenced pools with her trail of younglings following, an eagle swooped from heaven and flying high bore off one of her children to Telea: on the second day a mighty hawk robbed her of yet another and bore it to Kemenūme. Now that nursling that was brought to Kemenūme waxed and became a trader and cometh not into this sad tale: but that one whom the hawk brought to Telea he it is whom men name Kalervō: while a third of the nurslings that remained behind men speak oft of him and name him Untamō the Evil, and a fell sorcerer and man of power did he become.

And Kalervo dwelt beside the rivers of fish and had thence much sport and good meat, and to him had his wife borne in years past both a son and a daughter and was even now again nigh to childbirth. And in those days did Kalervo’s lands border on the confines of the dismal realm of his mighty brother Untamo; who coveted his pleasant river lands and its plentiful fish.

So coming he set nets in Kalervo’s fish waters and robbed Kalervo of his angling and brought him great grief. And bitterness arose between the brothers, first that and at last open war. After a fight upon the river banks in which neither might overcome the other, Untamo returned to his grim homestead and sat in evil brooding, weaving (in his fingers) a design of wrath and vengeance.

He caused his mighty cattle to break into Kalervo’s pastures and drive his sheep away and devour their fodder. Then Kalervo let forth his black hound Musti to devour them. Untamo then in ire mustered his men and gave them weapons; armed his henchmen and slave lads with axe and sword and marched to battle, even to ill strife against his very brother.

And the wife of Kalervoinen sitting nigh to the window of the homestead descried a scurry arising of the smoke army in the distance, and she spake to Kalervo saying, ‘Husband, lo, an ill reek ariseth yonder: come hither to me. Is it smoke I see or but a thick[?] gloomy cloud that passeth swift: but now hovers on the borders of the cornfields just yonder by the new-made pathway?’

Then said Kalervo in heavy mood, ‘Yonder, wife, is no reek of autumn smoke nor any passing gloom, but I fear me a cloud that goeth nowise swiftly nor before it has harmed my house and folk in evil storm.’ Then there came into the view of both Untamo’s assemblage and ahead could they see the numbers and their strength and their gay scarlet raiment. Steel shimmered there and at their belts were their swords hanging and in their hands their stout axes gleaming and neath their caps their ill faces lowering: for ever did Untamoinen gather to him cruel and worthless carles.

And Kalervo’s men were out and about the farm lands so seizing axe and shield he rushed alone on his foes and was soon slain even in his own yard nigh to the cowbyre in the autumn-sun of his own fair harvest-tide by the weight of the numbers of foemen. Evilly Untamoinen wrought with his brother’s body before his wife’s eyes and foully entreated his folk and lands. His wild men slew all whom they found both man and beast, sparing only Kalervo’s wife and her two children and sparing them thus only to bondage in his gloomy halls of Untola.

Bitterness then entered the heart of that mother, for Kalervo had she dearly loved and dear been to him and she dwelt in the halls of Untamo caring naught for anything in the sunlit world: and in due time bore amidst her sorrow Kalervo’s babes: a man-child and a maid-child at one birth. Of great strength was the one and of great fairness the other even at birth and dear to one another from their first hours: but their mother’s heart was dead within, nor did she reck aught of their goodliness nor did it gladden her grief or do better than recall the old days in their homestead of the smooth river and the fish waters among the reeds and the thought of the dead Kalervo their father, and she named the boy Kullervo, or ‘wrath’, and his daughter Wanōna, or ‘weeping’. And Untamo spared the children for he thought they would wax to lusty servants and he could have them do his bidding and tend his body nor pay them the wages he paid the other uncouth carles. But for lack of their mother’s care the children were reared in crooked fashion, for ill cradle rocking meted to infants by fosterers in thralldom: and bitterness do they suck from breasts of those that bore them not.

The strength of Kullervo unsoftened turned to untameable will that would forego naught of his desire and was resentful of all injury. And a wild lone-faring maiden did Wanōna grow, straying in the grim woods of Untola so soon as she could stand – and early was that, for wondrous were these children and but one generation from the men of magic. And Kullervo was like to her: an ill child he ever was to handle till came the day that in wrath he rent in pieces his swaddling clothes and kicked with his strength his linden cradle to splinters – but men said that it seemed he would prosper and make a man of might and Untamo was glad, for him thought he would have in Kullervo one day a warrior of strength and a henchman of great stoutness.

Nor did this seem unlike, for at the third month did Kullervo, not yet more than knee-high, stand up and spake in this wise on a sudden to his mother who was grieving still in her yet green anguish. ‘O my mother, o my dearest why grievest thou thus?’ And his mother spake unto him telling him the dastard tale of the Death of Kalervo in his own homestead and how all he had earned was ravished and slain by his brother Untamo and his underlings, and nought spared or saved but his great hound Musti who had returned from the fields to find his master slain and his mistress and her children in bondage, and had followed their exile steps to the blue woods round Untamo’s halls where now he dwelt a wild life for fear of Untamo’s henchmen and ever and anon slaughtered a sheep and often at the night could his baying be heard: and Untamo’s underlings said it was the hound of Tuoni Lord of Death though it was not so.

All this she told him and gave him a great knife curious wrought that Kalervo had worn ever at his belt if he fared afield, a blade of marvellous keenness made in his dim days, and she had caught it from the wall in the hope to aid her dear one.

Thereat she returned to her grief and Kullervo cried aloud, ‘By my father’s knife when I am bigger and my body waxeth stronger then will I avenge his slaughter and atone for the tears of thee my mother who bore me.’ And these words he never said again but that once, but that once did Untamo overhear. And for wrath and fear he trembled and said he will bring my race in ruin for Kalervo is reborn in him.

And therewith he devised all manner of evil for the boy (for so already did the babe appear, so sudden and so marvellous was his growth in form and strength) and only his twin sister the fair maid Wanōna (for so already did she appear, so great and wondrous was her growth in form and beauty) had compassion on him and was his companion in their wandering the blue woods: for their elder brother and sister (of which the tale told before), though they had been born in freedom and looked on their father’s face, were more like unto thralls than those orphans born in bondage, and knuckled under to Untamo and did all his evil bidding nor in anything recked to comfort their mother who had nurtured them in the rich days by the river.

And wandering in the woods a year and a month after their father Kalervo was slain these two wild children fell in with Musti the Hound. Of Musti did Kullervo learn many things concerning his father and Untamo and of things darker and dimmer and farther back even perhaps before their magic days and even before men as yet had netted fish in Tuoni the marshland.

Now Musti was the wisest of hounds: nor do men say ever aught of where or when he was whelped but ever speak of him as a dog of fell might and strength and of great knowledge, and Musti had kinship and fellowship with the things of the wild, and knew the secret of the changing of skin and could appear as wolf or bear or as cattle great or small and could much other magic besides. And on the night of which it is told, the hound warned them of the evil of Untamo’s mind and that he desired nothing so much as Kullervo’s death {and to Kullervo he gave three hairs from his coat, and said, ‘Kullervo Kalervanpoika, if ever you are in danger from Untamo take one of these and cry ‘Musti O! Musti may thy magic aid me now’, then wilt thou find a marvellous aid in thy distress.’}

And next day Untamo had Kullervo seized and crushed into a barrel and flung into the waters of a rushing torrent – that seemed like to be the waters of Tuoni the River of Death to the boy: but when they looked out upon the river three days after, he had freed himself from the barrel and was sitting upon the waves fishing with a rod of copper with a silken line for fish, and he ever remained from that day a mighty catcher of fish. Now this was the magic of Musti.

And again did Untamo seek Kullervo’s destruction and sent his servants to the woodland where they gathered mighty birch trees and pine trees from which the pitch was oozing, pine trees with their thousand needles. And sledgefuls of bark did they draw together, and great ash trees a [hundred] fathoms in length: for lofty in sooth were the woods of gloomy Untola. And all this they heaped for the burning of Kullervo.

They kindled the flame beneath the wood and the great bale-fire crackled and the smell of logs and acrid smoke choked them wondrously and then the whole blazed up in red heat and thereat they thrust Kullervo in the midst and the fire burned for two days and a third day and then sat there the boy knee-deep in ashes and up to his elbows in embers and a silver coal-rake he held in his hand and gathered the hottest fragments around him and himself was unsinged.

Untamo then in blind rage seeing that all his sorcery availed nought had him hanged shamefully on a tree. And there the child of his brother Kalervo dangled high from a great oak for two nights and a third night and then Untamo sent at dawn to see whether Kullervo was dead upon the gallows or no. And his servant returned in fear: and such were his words: ‘Lord, Kullervo has in no wise perished as yet: nor is dead upon the gallows, but in his hand he holdeth a great knife and has scored wondrous things therewith upon the tree and all its bark is covered with carvings wherein chiefly is to be seen a great fish (now this was Kalervo’s sign of old) and wolves and bears and a huge hound such as might even be one of the great pack of Tuoni.’

Now this magic that had saved Kullervo’s life was the last hair of Musti: and the knife was the great knife Sikki: his father’s, which his mother had given to him: and thereafter Kullervo treasured the knife Sikki beyond all silver and gold.

Untamoinen felt afraid and yielded perforce to the great magic that guarded the boy, and sent him to become a slave and to labour for him without pay and but scant fostering: indeed often would he have starved but for Wanōna who, though Unti treated her scarcely better, spared her brother much from her little. No compassion for these twins did their elder brother and sister show, but sought rather by subservience to Unti to get easier life for themselves: and a great resentment did Kullervo store up for himself and daily he grew more morose and violent and to no one did he speak gently but to Wanōna and not seldom was he short with her.

So when Kullervo had waxed taller and stronger Untamo sent for him and spake thus: ‘In my house I have retained you and meted wages to you as methought thy bearing merited – food for thy belly or a buffet for thy ear: now must thou labour and thrall or servant work will I appoint for you. Go now, make me a clearing in the near thicket of the Blue Forest. Go now.’ And Kuli went. But he was not ill pleased, for though but of two years he deemed himself grown to manhood in that now he had an axe set in hand, and he sang as he fared him to the woodlands.

Song of Sākehonto in the woodland:

Now a man in sooth I deem me

Though mine ages have seen few summers

And this springtime in the woodlands

Still is new to me and lovely.

Nobler am I now than erstwhile

And the strength of five within me

And the valour of my father

In the springtime in the woodlands

Swells within me Sākehonto.

O mine axe my dearest brother –

Such an axe as fits a chieftain,

Lo we go to fell the birch-trees

And to hew their white shafts slender:

For I ground thee in the morning

And at even wrought a handle;

And thy blade shall smite the tree-boles

And the wooded mountains waken

And the timber crash to earthward

In the springtime in the woodland

Neath thy stroke mine iron brother.

And thus fared Sākehonto to the forest slashing at all that he saw to the right or to the left, him recking little of the wrack, and a great tree-swathe lay behind him for great was his strength. Then came he to a dense part of the forest high up on one of the slopes of the mountains of gloom, nor was he afraid for he had affinity with wild things and Mauri’s [Musti’s] magic was about him, and there he chose out the mightiest trees and hewed them, felling the stout at one blow and the weaker at a half. And when seven mighty trees lay before him on a sudden he cast his axe from him that it half cleft through a great oak that groaned thereat: but the axe held there quivering.

But Sāki shouted, ‘May Tanto Lord of Hell do such labour and send Lempo for the timbers fashioning.’

And he sang:

Let no sapling sprout here ever

Nor the blades of grass stand greening

While the mighty earth endureth

Or the golden moon is shining

And its rays come filtering dimly

Through the boughs of Saki’s forest.

Now the seed to earth hath fallen

And the young corn shooteth upward

And its tender leaf unfoldeth

Till the stalks do form upon it.

May it never come to earing

Nor its yellow head droop ripely

In this clearing in the forest

In the woods of Sākehonto.

And within a while came forth Ūlto to gaze about him to learn how the son of Kampo his slave had made a clearing in the forest but he found no clearing but rather a ruthless hacking here and there and a spoilage of the best of trees: and thereon he reflected saying, ‘For such labour is the knave unsuited, for he has spoiled the best timber and now I know not whither to send him or to what I may set him.’

But he bethought him and sent the boy to make a fencing betwixt some of his fields and the wild; and to this work then Honto set out but he gathered the mightiest of the trees he had felled and hewed thereto others: firs and lofty pines from blue Puhōsa and used them as fence stakes; and these he bound securely with rowans and wattled: and made the tree-wall continuous without break or gap: nor did he set a gate within it nor leave an opening or chink but said to himself grimly, ‘He who may not soar swift aloft like a bird nor burrow like the wild things may never pass across it or pierce through Honto’s fence work.’

But this over-stout fence displeased Ūlto and he chid his slave of war for the fence stood without gate or gap beneath, without chink or crevice resting on the wide earth beneath and towering amongst Ukko’s clouds above.

For this do men call a lofty Pine ridge ‘Sāri’s hedge’.

‘For such labour,’ said Ūlto, ‘art thou unsuited: nor know I to what I may set thee, but get thee hence, there is rye for threshing ready.’ So Sāri got him to the threshing in wrath and threshed the rye to powder and chaff that the winds of Wenwe took it and blew as a dust in Ūlto’s eyes, whereat he was wroth and Sāri fled. And his mother was feared for that and Wanōna wept, but his brother and elder sister chid them for they said that Sāri did nought but make Ūlto angered and of that anger’s ill did they all have a share while Sāri skulked the woodlands. Thereat was Sāri’s heart bitter, and Ūlto spake of selling as a bond slave into a distant country and being rid of the lad.

His mother spake then pleading, ‘O Sārihontō if you fare abroad, if you go as a bond slave into a distant country, if you perish among unknown men, who will have thought for thy mother or daily tend the hapless dame?’ And Sāri in evil mood answered singing out in light heart and whistling thereto:

Let her starve upon a haycock

Let her stifle in the cowbyre

And thereto his brother and sister joined their voices saying,

Who shall daily aid thy brother?

Who shall tend him in the future?

To which he got only this answer,

Let him perish in the forest

Or lie fainting in the meadow.

And his sister upbraided him saying he was hard of heart, and he made answer. ‘For thee treacherous sister though thou be a daughter of Keime I care not: but I shall grieve to part from Wanōna.’

Then he left them and Ūlto thinking of the lad’s size and growing strength relented and resolved to set him yet to other tasks, and is it told how he went to lay his largest drag-net and as he grasped his oar asked aloud, ‘Now shall I pull amain with all my vigour or with but common effort?’ And the steersman said: ‘Now row amain, for thou canst not pull this boat atwain.’

Then Sāri Kampa’s son rowed with all his might and sundered the wood rowlocks and shattered the ribs of juniper and the aspen planking of the boat he splintered.

Quoth Ūlto when he saw, ‘Nay, thou understandst not rowing, go thresh the fish into the dragnet: maybe to more purpose wilt thou thresh the water with threshing-pole than with foam.’ But Sāri as he was raising his pole asked aloud, ‘Shall I thresh amain with manly vigour or but leisurely with common effort threshing with the pole?’ And the net-man said, ‘Nay, thresh amain. Wouldst thou call it labour if thou threshed not with thy might but at thine ease only?’ So Sāri threshed with all his might and churned the water to soup and threshed the net to tow and battered the fish to slime. And Ūlto’s wrath knew no bounds and he said, ‘Utterly useless is the knave: whatsoever work I give him he spoils from malice: I will sell him as a bond-slave in the Great Land. There the Smith Āsemo will have him that his strength may wield the hammer.’

And Sāri wept in wrath and in bitterness of heart for his sundering from Wanōna and the black dog Mauri. Then his brother said, ‘Not for thee shall I be weeping if I hear thou has perished afar off. I will find himself a brother better than thou and more comely too to see.’ For Sāri was not fair in his face but swart and illfavoured and his stature assorted not with his breadth. And Sāri said,

Not for thee shall I go weeping

If I hear that thou hast perished:

I will make me such a brother –

with great ease: on him a head of stone and a mouth of sallow, and his eyes shall be cranberries and his hair of withered stubble: and legs of willow twigs I’ll make him and his flesh of rotten trees I’ll fashion – and even so he will be more a brother and better than thou art.’

And his elder sister asked whether he was weeping for his folly and he said nay, for he was fain to leave her and she said that for her part she would not grieve at his sending nor even did she hear he had perished in the marshes and vanished from the people, for so she should find herself a brother and one more skilful and more fair to boot. And Sāri said, ‘Nor for you shall I go weeping if I hear that thou hast perished. I can make me such a sister out of clay and reeds with a head of stone and eyes of cranberries and ears of water lily and a body of maple, and a better sister than thou art.’

Then his mother spake to him soothingly.

Oh my sweet one O my dearest

I the fair one who has borne thee

I the golden one who nursed thee

I shall weep for thy destruction

If I hear that thou hast perished

And hast vanished from the people.

Scarce thou knowest a mother’s feelings

Or a mother’s heart it seemeth

And if tears be still left in me

For my grieving for thy father

I shall weep for this our parting

I shall weep for thy destruction

And my tears shall fall in summer

And still hotly fall in winter

Till they melt [the] snows around me

And the ground is bared and thawing

And the earth again grows verdant

And my tears run through the greenness.

O my fair one O my nursling

Kullervoinen Kullervoinen

Sārihonto son of Kampa.

But Sāri’s heart was black with bitterness and he said, ‘Thou wilt weep not and if thou dost, then weep: weep till the house is flooded, weep until the paths are swimming and the byre a marsh, for I reck not and shall be far hence.’ And Sāri son of Kampa did Ūlto take abroad with him and through the land of Telea where dwelt Āsemo the smith, nor did Sāri see aught of Oanōra [Wanōna] at his parting and that hurt him: but Mauri followed him afar off and his baying in the nighttime brought some cheer to Sāri and he had still his knife Sikki.

And the smith, for he deemed Sāri a worthless knave and uncouth, gave Ūlto but two outworn kettles and five old rakes and six scythes in payment and with that Ūlto had to return content not.

And now did Sāri drink not only the bitter draught of thralldom but eat the poisoned bread of solitude and loneliness thereto: and he grew more ill favoured and crooked, broad and illknit and knotty and unrestrained and unsoftened, and fared often into the wild wastes with Mauri: and grew to know the fierce wolves and to converse even with Uru the bear: nor did such comrades improve his mind and the temper of his heart, but never did he forget in the deep of his mind his vow of long ago and wrath with Ūlto, but no tender feelings would he let his heart cherish for his folk afar save a[t] whiles for Wanōna.

Now Āsemo had to wife the daughter [of] Koi Queen of the marshlands of the north, whence he carried magic and many other dark things to Puhōsa and even to Sutsi by the broad rivers and the reed-fenced pools. She was fair but to Āsemo alone sweet. Treacherous and hard and little love did she bestow on the uncouth thrall and little did Sāri bid for her love or kindness.

Now as yet Āsemo set not his new thrall to any labour for he had men enough, and for many months did Sāri wander in wildness till at the egging of his wife the smith bade Sāri become his wife’s servant and do all her bidding. And then was Koi’s daughter glad for she trusted to make use of his strength to lighten her labour about the house and to tease and punish him for his slights and roughness towards her aforetime.

But as may be expected, he proved an ill bondservant and great dislike for Sāri grew up in his [Āsemo’s] wife’s heart and no spite she could wreak against him did she ever forego. And it came to a day many and many a summer since Sāri was sold out of Dear Puhōsa and left the blue woods and Wanōna, that seeking to rid the house of his hulking presence the wife of Āsemo pondered deep and bethought her to set him as her herdsman and send him afar to tend her wide flocks in the open lands all about.

Then set she herself to baking: and in malice did she prepare the food for the neatherd to take with him. Grimly working to herself she made a loaf and a great cake. Now the cake she made of oats below with a little wheat above it, but between she inserted a mighty flint – saying the while, ‘Break thou the teeth of Sāri O flint: rend thou the tongue of Kampa’s son that speaketh always harshness and knows of no respect to those above him. For she thought how Sāri would stuff the whole into his mouth at a bite, for greedy he was in manner of eating, not unlike the wolves his comrades.

Then she spread the cake with butter and upon the crust laid bacon and calling Sāri bid him go tend the flocks that day nor return until the evening, and the cake she gave him as his allowance, bidding him eat not until the herd was driven into the wood. Then sent she Sāri forth, saying after him:

Let him herd among the bushes

And the milch kine in the meadow:

These with wide horns to the aspens

These with curved horns to the birches

That they thus may fatten on them

And their flesh be sweet and goodly.

Out upon the open meadows

Out among the forest borders

Wandering in the birchen woodland

And the lofty growing aspens.

Lowing now in silver copses

Roaming in the golden firwoods.

And as her great herds and her herdsman got them afar, something belike of foreboding seized her and she prayed to Ilu the God of Heaven who is good and dwells in Manatomi. And her prayer was in the fashion of a song and very long, whereof some was thus:

Guard my kine O gracious Ilu

From the perils in the pathway

That they come not into danger

Nor may fall on evil fortune.

If my herdsman is an ill one

Make the willow then a neatherd

Let the alder watch the cattle

And the mountain ash protect them

Let the cherry lead them homeward

In the milktime in the even.

If the willow will not herd them

Nor the mountain ash protect them

And the alder will not watch them

Nor the cherry drive them homeward

Send thou then thy better servants,

Send the daughters of Ilwinti

To guard my kine from danger

And protect my horned cattle

For a many are thy maidens

At thy bidding in Manoine

And skilled to herd the white kine

On the blue meads of Ilwinti

Until Ukko comes to milk them

And gives drink to thirsty Kēme.

Come thou maidens great and ancient

Mighty daughters of the Heaven

Come thou children of Malōlo

At Ilukko’s mighty bidding

O [Uorlen?] most wise one

Do thou guard my flock from evil

Where the willows will not ward them

Out across the quaking marshland

Where the surface ever shifteth

And the greedy depths are gulping.

O thou Sampia most lovely

Blow the honey-horn most gaily.

Where the alder will not tend them

Do thou pasture all my cattle

Making flowers upon the hummocks:

With the melody of the mead-horn

Make thou fair this heathland border

And enchant the skirting forest

That my kine have food and fodder,

And have golden hay in plenty

And the heads of silver grasses.

O Palikki’s little damsel

And Telenda thy companion

Where the rowan will not tend them

Dig my cattle wells all silver

Down on both sides of their pasture

With your straying feet of magic

Cause the grey springs to spout coolly

And the streams that flow by swiftly

And the speedy running rivers

Twixt the shining banks of grassland

To give drink of honey sweetness

That the herd may suck the water

And the juice may trickle richly

To their swelling teeming udders

And the milk may flow in runlets

And may foam in streams of whiteness.

But Kaltūse thrifty mistress

And arrester of all evil,

Where the wild things will not guard them

Fend the sprite of ill far from them

That no idle hands do milk them

And their milk on earth be wasted

That no drops flow down to Pūlu

And that Tanto drink not of it

But that when at Kame at milk tide

Then their milkstreams may be swollen

And the pails be overflowing

And the good wife’s heart be gladdened.

O Terenye maid of Samyan

Little daughter of the forests

Clad in soft and beauteous garments

With thy golden hair so lovely

And thy shoon of scarlet leather,

When the cherry will not lead them

Be their neatherd and their shepherd.

When the sun to rest has sunken

And the bird of Eve is singing

As the twilight draweth closer

Speak thou to my horned creatures

Saying come ye hoofed cattle

Come ye homeward trending homeward.

In the house ’tis glad and pleasant

Where the floor is sweet for resting

On the waste ’tis ill to wander

Looming down the empty shorelands

Of the many lakes of Sutse.

Therefore come ye horned creature

And the women fire will kindle

In the field of honeyed grasses

On the ground o’ergrown with berries.

[The following lines are offset to indicate a change of tone. Kirby’s edition does not so distinguish them, but notes in the Argument at the head of the Runo that it contains ‘the usual prayers and charms’ (Kirby Vol. 2, p. 78). Magoun gives the lines the heading ‘Charms for Getting Cattle Home, Lines 273–314’ (Magoun, p. 232).]

Then Palikki’s little damsel

And Telenda her companion

Take a whip of birch to scourge them

And of juniper to drive them

From the hold of Samyan’s cattle

And the gloomy slopes of alder

In the milktide of the evening.

[As above, these lines are offset to indicate a shift in tone and separate them from those preceding. Kirby’s Argument notes a charm for ‘protection from bears in the pastures’ (p. 78), while Magoun supplies the heading ‘Admonitory Charms Against Bears, Lines 315–542 (p. 232).]

O thou Uru O my darling

My Honeypaw that rules the forest

Let us call a truce together

In the fine days of the summer

In the good Creator’s summer

In the days of Ilu’s laughter

That thou sleepst upon the meadow

With thine ears thrust into stubble

Or conceal thee in the thickets

That thou mayst not hear cowbells

Nor the talking of the herdsman.

Let the tinkling and the lowing

And the ringing in the heathland

Put no frenzy yet upon thee

Nor thy teeth be seized with longing.

Rather wander in the marshes

And the tangle of the forest.

Let thy growl be lost in wastelands

And thy hunger wait the season

When in Samyan is the honey

All fermenting on the hillslopes

Of the golden land of Kēme

Neath the faring bees a-humming.

Let us make this league eternal

And an endless peace between us

That we live in peace in summer,

In the good Creator’s summer.

[As with the other separations, this indentation is offset to indicate change in tone, in this case the conclusion or peroration of the lady’s prayers. Neither Kirby nor Magoun so distinguishes these lines.