Читать книгу At the Coalface: The memoir of a pit nurse - Veronica Clark, Joan Hart - Страница 10

4 Going Home

ОглавлениеI went to see my doctor, who told me in no uncertain terms that I was so stressed out that I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. I felt it too. Mum was always arguing with Peter over nothing. He refused to kowtow to her, so we lived in a permanent stalemate with me caught in the middle. Secretly, I’d started applying for jobs in Doncaster to see what came up, although I never told a soul, apart from Dad and a staff nurse at work called Maggie.

‘We’ll miss you if you go, Joan,’ she sighed.

‘It’s just that no one will listen to me, Maggie. I feel as though I’m banging my head against a brick wall. It’s got so bad that I dread going home because Peter’s so headstrong that he won’t listen to me, not any more. He just seems intent on winning the argument with Mum, and she’s impossible to live with. I can’t win.’

Maggie looked at me. We were standing in the corridor at work with people flying past us but, thankfully, everyone was too busy to stop and eavesdrop on our conversation. Maggie thought for a moment and then spoke quietly.

‘If it’s that bad then I think your dad is right, Joan. I think you need to go home.’

I looked up at her.

‘Do you really think so?’

She nodded. ‘If it’s going to make you happy, then yes, I do.’

I knew I’d miss Hammersmith and my colleagues, but I felt caught between a rock and a hard place and I needed to escape for my own sanity. Weeks later, I received a response from a nursing home in Doncaster. I told Peter I was going home for the weekend when I was actually going for a job interview. I got the job, returned to London and handed in a month’s notice at work. Of course, people were shocked when I told them I was leaving.

‘We’re moving back to Yorkshire,’ I explained, only there was no ‘we’ about it.

One night, when Peter was still at work, I came home from the hospital and packed my suitcase. I worried he’d find it and stop me, so I hid it under some stuff at the back of the wardrobe, knowing he’d never think to look there. The following day, after everyone had left for work, I sat down and wrote Peter a note.

Dear Peter, I’ve been to see the doctor who says I’m on the verge of a nervous breakdown, I began. I read and reread the sentence. It sounded a little melodramatic written on the page, but it was true. My hand shook slightly as I continued. He says I need to get away so I’ve decided to go back to my dad’s house. I’ll be in touch later, lots of love, Joan x

The note was short and sweet but it said all it needed to say. I found it difficult to write because I hated the thought of running out on anyone, yet that’s exactly what I was doing. Unlike my mother, I didn’t have children and I was leaving purely because of the constant interference from both sides. I was convinced if I did stay it would only be ten times worse. But I was at the end of my tether and couldn’t see another way out. I had to leave London for my own sanity. I read the note again, folded the paper in half and ran my fingers along it to form a neat crease. I placed it inside a small white envelope, sealed it and propped it up against the teapot in the middle of the kitchen table. I glanced up at the clock on the wall; only a few more hours until my train left for Yorkshire. Deep down, I was terrified that Peter would finish work early and find me at home. Less than half an hour later, I closed the door on our rooms in Brackenbury Road, Shepherd’s Bush, and on my married life. I took the tube and headed over to King’s Cross station, fraught with anxiety.

What if Peter comes home and dashes over to look for me? How would I explain myself?

But I hadn’t thought that far ahead. All I knew was that, right then, I needed to go home so desperately that the homesickness ached inside my bones. I hid away in a corner of the café at King’s Cross station, watching the hand of the brown Bakelite clock slowly tick by.

Dad knew I was coming, so he’d prepared a bed for me. He picked me up from Doncaster station when I arrived, and I stayed the first night with him. The following morning, I travelled to the nursing home. I’d been told I’d be responsible for running the home along with two other trained staff. Unfortunately, one of those was a decrepit 80-year-old nun. The owner wasn’t much help either; she was bedridden due to a heart complaint, and she barked orders at me from her single bed. In many ways I felt sorry for her, but I soon realised, sick or not, she still wasn’t a very nice person.

‘I’ll need you to work 12-hour night shifts, five times a week,’ she informed me. The horror must have shown on my face because she quickly added, ‘But, of course, I’ll pay you a little extra.’

However, that was where her generosity started and ended. I discovered to my dismay that she kept the fridge firmly locked with a padlock and chain to stop staff from helping themselves. Not that there was much time to eat. She’d leave me a few slices of bacon and a drop of milk for my supper, but as the live-in help I felt I couldn’t complain. My bedroom was situated on the top floor. It was a small but clean room, and all I needed at that moment in time. The nursing home housed twenty-four patients: twelve were private patients with their own rooms on the first floor, while the other dozen NHS ones were mixed in together according to gender. I was assigned an auxiliary nurse to help me, which was a blessing, because I needed the extra pair of hands. One night, it was freezing cold even though the home had been fitted with a hot-water-boiler heating system.

‘Blimey, it’s bloody freezing in here!’ I remarked to the auxiliary as we turned the sheets over on a patient’s bed.

‘Didn’t you stoke the boiler?’ she asked, a little startled.

I looked up at her blankly.

‘The boiler. We have to stoke it every few hours to keep it going so that it doesn’t burn out,’ she said.

I ran downstairs to the basement and threw some coke on it to try to fire it back into life.

The following morning, after spending the night caring for twenty-four elderly patients, my work still wasn’t done because I had to cook everyone’s breakfast. I’d started at 8 o’clock the evening before but I couldn’t leave or go to bed until 8 o’clock the following morning, when the day-shift workers arrived. It was such gruelling work that I felt less like a nurse and more like Cinderella, locked away in the kitchen.

Shortly afterwards, we had a death in the nursing home. I tried to ring the doctor to come and certify death, but he was already out on his emergency calls and I couldn’t get hold of anyone else. With a dead body and no doctor, the auxiliary nurse and I had to lift the poor deceased woman and wrap her inside a canvas sheet. We laid her on a table in the garage, which was used as a makeshift mortuary, until 9 o’clock the following morning when the doctor finally arrived to certify death. I began to hate the nursing home with a passion. Strangely, I didn’t mind the long hours – it felt good to keep busy because when I was busy I didn’t think about Peter or our marriage. But I hated the fact that they used me as nothing more than a qualified skivvy.

One day, my sister, Ann, called for me. By this time, Ann was training to become a hairdresser. She had no money so she’d walked 2 miles to reach me. I was summoned downstairs by another member of staff, who tapped on my bedroom door.

‘Your sister is waiting in reception for you.’

I was surprised but also a little worried. I’d been invited over to Dad’s house for dinner later that evening because it was my night off, so I worried what was so important that it couldn’t wait. I walked downstairs and, as soon as I saw her standing in reception I ran over to give her a hug. I beckoned her to follow me through to the front-room reception, where she sat down on one of the old, worn leather armchairs. But Ann looked uncomfortable – a little troubled, as though there was something on her mind.

‘Ann,’ I said, cutting straight to the point, ‘whatever’s the matter?’

Ann’s face crumpled as she turned to face me. Something was wrong, I could just tell.

‘Dad says I’m not supposed to tell you in case you don’t come home later, but Peter’s at our house and he’s looking for you.’

My heart leapt inside my chest. I’d left London less than a fortnight before, but Peter was here and now he wanted to speak to me and sort things out. I felt a small glimmer of hope. I asked Ann to wait while I nipped upstairs to get my bag so we could leave. As soon as I approached the front gate at home, my family spotted me through the window and made a sharp exit. It would’ve been comical if it hadn’t been such a serious situation. Dad came outside. He patted me lightly on the arm and muttered something in a low voice.

‘I’ve had a talk with him. He knows what’s going on here and he understands. Now it’s your turn,’ he said, giving me a gentle nudge towards the back door.

As soon as I walked into the house, Peter stood up. He came over, took me in his arms and gave me a hug and a kiss. As he pulled away I gazed into his face – he looked broken. I felt a pang of guilt because I knew I’d done it to him. But I’d been so unhappy, and sometimes desperate situations call for desperate measures. We sat and talked all afternoon. We spoke about our situation in London, living above my mother and the general interference from both sides.

‘Your mother is as bad as mine,’ I eventually sighed. ‘Neither of them wants us to be together.’

Peter agreed.

‘So I can’t go back there,’ I insisted.

Peter nodded. ‘I know. I’ve been speaking to your dad. He says you’ve lived in my world long enough so it’s time I came to live in yours, here in Yorkshire.’

I smiled to myself. Good old Dad.

‘He even said he’d get me a job,’ Peter continued, breaking my thoughts. ‘Reckons he could fix me up with something at the pit.’

‘Oh, Peter, that’s brilliant!’

And it was, because it meant Peter and I could be together and far away from our two meddling mothers. The decision had been made; Peter would leave London and move to Doncaster.

‘I’ve missed you so much,’ I wept.

‘Me too,’ he said, wrapping his arms around me. ‘Your mother has been such a cow to me. It’s been horrible without you, Joan. I just want to make you happy – I want us both to be happy.’

We spoke long into the afternoon and then he told me something quite unexpected.

‘You do know your mother came to Doncaster looking for you after you’d left London, don’t you?’

I was astounded.

‘Yes,’ he continued, ‘she scoured all the hospitals in the area but no one had a record of a Joan Hart, so in the end she came back to London.’

Somehow, the fact that both Mum and Peter had come looking for me filled me with hope. I thought no one would have even noticed that I’d gone, but I’d been wrong.

‘I love you with all my heart,’ I said, taking his hand in mine.

‘Me too, Joan, me too.’

Dad was relieved when we told him we’d made up. But first, Peter had to return down south to serve his notice. In a way it made things easier because it gave me time to find us a suitable house to live in.

‘I think I can help you there,’ Harry, my step-brother, said.

Harry was Polly’s eldest son. He was a successful businessman who owned four busy shops, so he mixed in high circles. One of his acquaintances was a flying officer in the RAF who owned a house he was looking to rent out in a place called Balby, situated on the outskirts of Doncaster. The house, on Stanley Street, sounded charming by description, but if I’d imagined a palatial home then I was sorely mistaken. The two up, two down was a complete tip! To make matters worse, the walls rattled every time a train went past on the main line, which ran along the bottom of the garden right beside the outside loo! Still, with little else available, we took it – beggars can’t be choosers. Thankfully, Tony and Ann offered to help clean it.

‘Don’t worry, Joan. We’ll soon have it sorted!’ Ann said breezily, rolling up her sleeves. I admired her optimism.

There were so many empty beer bottles stashed under the sink and in various hidey-holes around the house that, by the time we’d collected and returned them all to the off-licence – or beer-off, as we called it – we’d earned ourselves £5! The previous tenant, it seemed, had been partial to a drink or three. The house was freezing cold, but thankfully it had a fireplace in the living room, which doubled up as the dining room. Ann would cart huge carrier bags of coal over to me from home, travelling all the way on the bus from Woodlands, because Dad got it for free. It was a good 8 miles away, so her arms always felt a little longer by the time she arrived. I couldn’t have cleaned it without her and Tony because it was the dirtiest place I’d ever seen – even Elsie would have flinched. We discovered some strange things, but the strangest and most interesting find came right at the end, when we tackled the basement.

‘Here, look what I’ve found,’ Tony called as I squinted in the dim light. I could just make him out – he was holding something in the air, high up above his head. He started clacking them with his fingers. At first I thought they were a pair of castanets, but as Ann and I got closer we realised it was a pair of false teeth! Ann screamed the house down, but I fell about laughing and so did Tony. It was nice to laugh; otherwise I think I might have cried. Still, we did what we could with the rest of the house. Ann and I bought metres of red gingham checked material from Doncaster market so that we could make curtains. We hung them up in the kitchen window, and strung them on a piece of elastic in a ‘skirt’ around the bottom of the big white butler’s sink.

Peter visited whenever he could to help out, but without a car he had to catch the train. It was such a long journey that half the weekend was taken up by travel alone. Peter also needed to find himself a job. True to his word, Dad had heard of a position at Brodsworth Colliery. He put Peter’s name forward and helped set him on his way.

‘It’s hard graft, mind you,’ he said, sizing Peter up. I could tell he was wondering if my southern husband was up to the job.

Peter took it, but four weeks later Dad’s north–south prejudice was confirmed when Peter was laid off sick with a sprained back. He was a highly skilled plumber, so he wasn’t used to digging or hard labour to earn a living.

With a house to move into, I gave my notice at the nursing home and secured a better position as Deputy Matron at a day nursery that cared for babies and children aged from a few months old up to two years. The nursery was different to others in the area in that it was used by a lot of one-parent families, which was something I identified with. The matron was an unmarried mother with a little boy who attended the same nursery. I admired her because this was a time when many mothers were so shamed by having a baby out of wedlock that they’d simply abandon them or give them up for adoption, but not this lady. She was incredible, and I had nothing but the utmost respect for how she loved and cared for her little boy.

The working hours were almost as gruelling as the nursing home. When I arrived at 6 a.m., I’d find half a dozen prams already lined up and waiting outside the main door. The parents would’ve gone, usually straight off to work. There was no worry or concern back then that someone might steal a baby, because everyone did the same thing. Mind you, it was also a blissful time when you could leave your front door unlocked without fear of being burgled or murdered in your bed. If I was shocked by the babies being left in the morning, then I was even more surprised when the same parents forgot to pick them up at night. More often than not there was usually a mix-up or breakdown in communication. One parent would presume a friend or relative was picking the child up and vice versa. A lot of the parents were bus drivers or conductors working long shifts, so I’d have to ring Doncaster police station to get them to trace the missing mum or dad.

‘Hello, its Elmfield nursery. I’m afraid we’ve got another no-show,’ I told the officer on the other end of the phone.

‘Another one?’ he gasped. ‘How on earth can you forget to pick up your child?’ The line went silent for a moment and I visualised the officer shaking his head in despair. ‘Don’t worry; someone will be along shortly.’

Whenever I had a situation like that, Peter would sit and wait with me until the police officer arrived. The officer would try to track down the parent, who always had a valid excuse, but they’d still be given a police caution.

I loved working with the children, and I often imagined myself as a mother with a brood of my own. All the same, it was nice to hand them back at the end of the day and switch off. I’d worked at the nursery for almost a year when Dad called to see me. He’d heard of a new job at Brodsworth Colliery.

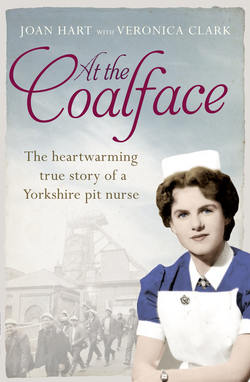

‘They’re looking to set up a new medical centre, so they need a fully qualified nursing officer. I’ve put your name forward. Hope that’s all right?’

It was, because by now I knew it was time to move on, although it didn’t stop the nerves rising inside my stomach. I was still in my early twenties – in many ways I was still learning – yet at the pit I knew I’d be in charge of thousands of men. I’d always been confident in my own nursing world of hospitals and sterile wards, but this was a different type of nursing – this was industrial nursing, which I’d never done before. But I wasn’t proud. I’d ask for help if I needed it.

Although I realised it’d be a whole different ball game, I trusted my father and his judgement. Ultimately, I knew he wouldn’t have recommended me if he didn’t think I was up to the job.