Читать книгу A Socialist Defector - Victor Grossman - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1—Wrong Way?

I was ten years old in the summer of 1938 when a jolly, somewhat nutty airplane mechanic named Corrigan, instead of flying back from New York to California in his air jalopy as officially authorized, flew it solo, secretly and illegally, across the Atlantic to Ireland. On his return he got a hilarious confetti welcome—and the term “wrong-way Corrigan” went into the language of the day.

Fourteen years later I did something maybe even nuttier. The water barrier I crossed was far narrower, about 400 or 500 yards across the Danube River. But I didn’t fly, I fled, and not in a plane but swimming. At that time the river divided the U.S. Zone from the USSR Zone in Austria, so I was piercing the Iron Curtain—but also in the wrong direction. I certainly did not expect any confetti welcome. Nor did I get any.

That cold water immersion obviously didn’t kill me. But didn’t it at least cure me? And didn’t it ruin my life, making me a traitor to everything decent in the world, starting with the United States? What in the name of God or the devil made me commit such an amazing blunder? How soon did I begin to regret it? This book will try to answer those questions, while raising many new ones, for me and possibly some readers as well.

My immediate motivation was clear. Drafted into the U.S. Army in 1951 in the icy days later known as the McCarthy era, and in great fear of the new McCarran Act with its threat of unlimited years in prison as a “foreign agent” (or in concentration camps authorized by the same law), I signed the paper required of all Korean War draftees that I had never been a member of the 120 listed organizations, many long gone, all “taboo” and nearly all leftist. I had indeed been in about a dozen, not only the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Appeal (for Spanish Civil War victims) and the Southern Negro Youth Congress (out of sympathy and support) but also, as a student opposed to atom bombs, anti-union laws, and racism—and believing in socialism—in the most ostracized of them all, the Communist Party. I was not a card-carrying member only because the Party no longer gave out membership cards.

My hope was that if I kept my nose clean and my mouth shut then the two years of army service might come and go without a check on my past delinquency. At first, I was very lucky, I was sent not to Korea but to Germany. Then luck turned sharply against me: they did check up—and discovered my perjury. Ordered to report to a military judge, I read the threatened punishment for my crime—up to $10,000 and five years in prison. Five years behind bars, in Leavenworth? With no one to consult or advise me I simply panicked. The threat of prison is what made me wade in and swim across the swift but not at all blue Danube.

What has that got to do with this book? Everything. Upon arrival, the Soviet authorities, without consulting my possible preferences, held me briefly in confinement and then released me into a town of East Germany, the still very young German Democratic Republic, or GDR.

Thus, after twenty-four years growing up in New York and New Jersey, after nine schools, public and private (two years each at posh Dalton and Fieldston Schools), a B.A. at Harvard, unskilled factory work in Buffalo, and a long hitchhike trip from one U.S. coast to the other and back, I now became an inside witness to the growth, development, and demise of the GDR and of what has happened since. As a worker again and once more as a student, when I became the one and only person in the world with a diploma from both Harvard and the Karl Marx University of Leipzig (and since the latter has dropped the name, I will undoubtedly retain this distinction) I became finally a freelance journalist and lecturer and got to visit nearly every town and city and many a village. I saw, heard, and took part in almost every phase of GDR life, while my base and main vantage point was my apartment near downtown East Berlin, less than a mile from its famous, or infamous, Wall.

I think I can hear two reactions: one sympathetic: “My God, you poor guy! How in blazes did you survive such a long ordeal in that hellhole?”

Or unsympathetic: “Thirty-eight years locked up in there? Serves you damned right for your treacherous act!”

To the second reaction I would mildly absolve myself by noting that the man who framed the law that frightened me from the start, Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada, turned out to be the rottenest, most vicious anti-Semite in Washington, DC. That paper, which my fear made me sign when I was drafted, thus totally altering my life, was later ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. And I can add that in 1994 the U.S. Army mercifully decided to discharge me, with no punishment at all, after forty-two years. But to both reactions I would reply that life in general, politics in particular, and most specifically the GDR story, are just not that simple.

My first twenty-four years were spent in the world’s leading land of free enterprise. By strange circumstance, in 1952, I landed in a country with a “planned economy,” variously referred to as communist, “real socialist,” “command economy,” or some far saltier appellations. In 1990, after thirty-eight years, this time with no swimming involved, I was again back in a free market system.

Even at my ripe old age, I make no claim to be wiser or more correct than anyone else. But we live in a time when many good people are hunting for answers to severe problems facing our world, often fearlessly exploring a wide range of possible solutions. My life journey taught me lessons and led to conclusions that might be of interest, even value. I offer no ready-to-bake recipes but only some ideas, if only because, more than most Americans, I had an unusual opportunity to make comparisons.

“What? Opportunity? Comparisons?” some voices will retort. “Are you stupid? Or simply stubborn? Need anyone even consider contradictions between good and evil, justice and injustice, freedom and totalitarian dictatorship? Don’t you know the words of that great freedom-fighter Winston Churchill: ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others’? Can there really be any doubts about that corpse of a misbegotten regime daring to call itself the German Democratic Republic?”

Was it my ancestral background, my schooling, or my checkered past that imbued me with a firm rule to look at things “on the one hand”—but then, too, “on the other hand”? Life and politics are hardly drawn in one or even two dimensions. This does not always apply, it is true, and not everywhere. But, rightly or wrongly, this habit forced its way into my thinking about the GDR and East Berlin both before and after the “fall of the Wall” in 1989–90. However, before I reflect about capitalism, socialism, communism, freedom, and democracy or any other isms or solutions for the world’s troubles, I want to describe some of what I experienced.

2—Future Dreams in an Ancient Town

After many hours, and finding no sign of the Red Army, I was finally picked up by the Austrian police, barefoot and bedraggled from my fateful Danubian swim, and escorted, as I demanded, to the Soviet Kommandantur (because, very wisely, I did not trust the cops). I was briefly questioned, then driven the next day to Soviet HQ in Baden near Vienna, and politely but unceremoniously locked up in a small, very primitive cell, under armed guard, for a period of two weeks. After some initial skepticism about the long day I had spent hunting for the Soviet armed forces I had expected to find patrolling this stretch of the Iron Curtain, the guards became friendly. I had fascinating discussions on literature and cinema with the armed soldier outside my cell; using my ten, at most twenty Russian words, mostly from names of books. I would say “Anna Karenina?” He would gradually understand me despite my false pronunciation and then say with a big smile: “Da, da, chital, khorosho!”—“Yes, yes. I’ve read it. Good!” Since I had also seen a number of Soviet films, like Gulliver and Lenin in October, these exchanges and evaluations lasted a while, to our mutual satisfaction, and I learned new vocabulary. Most essential was “ubornaya” for “toilet.”

After twice reading the three available books in English, one a history of Scotland, and getting a complete new outfit of clothes and accessories (“And for you a red tie!”), I was driven to an unknown destination, which turned out to be the GDR, and was placed in an isolated room in a building in Potsdam, near Berlin. I had a one-hour daily walk in the garden behind the guarded house and about once a week got a visit from a friendly fellow called “George,” with only a slight Russian accent, who asked me about myself, chatted about politics, showed me match tricks, and asked if I was interested in moving to Western Europe. I definitely wasn’t and that was dropped.

I suggested assuming a new name to protect my family from difficulties, so he told me to choose one. Try as I could, I could think of no new moniker. When a decision became necessary he asked if Victor Grossman was okay. I didn’t like it at all but, having failed in my own search, accepted it, also in the knowledge that unlike, say, Murphy or Johnson, it retained some of my Jewish identity (though it was seen by some as German, until I corrected them).

After two months, and another set of clothes from the Soviets plus one now from the GDR authorities, I landed in Bautzen, a town of 45,000 inhabitants in a corner of East Germany near the Czech and Polish borders. What I found was certainly not the communist-type Utopia I may have been dreaming of. The war, less than eight years earlier, had not spared the town, long a battle-point: a few remaining ruins, cleared lots, and a cemetery of Soviet soldiers attested to that. But I saw no signs of the hunger or rags that press reports might have led me to expect; life seemed to move along fairly normally. The few vehicles were old, sometimes unusual: delivery trucks with two wheels in back but one in front, or cars with wood ovens mounted in back as motors. In 1952 the shops offered basic groceries and textiles and were quite spartan; I recall long hunts for handkerchiefs and a new washrag. For a few weeks razor blades were short, which meant lining up to get old ones resharpened. Toilet paper was unavailable, so newspapers or pulpy magazines (but no Sears and Roebucks catalogues) were torn into neat squares.

It seems that the Soviet authorities had chosen Bautzen to settle deserters from Western armies because it was as far as possible from West Berlin and West German borders but not directly on a crossing point to Poland or Czechoslovakia. Also, it was large enough to provide jobs but not too large to lose track of us in a big city atmosphere. Our numbers changed, since there were new arrivals every month or so but a similar number would abscond westward again. About fifteen to twenty were Americans, about ten were British, and five to ten were French with a similar number from North African French colonies who deserted so as not to be sent to fight in Indochina. There were a few from the Netherlands, a Spaniard, an Irishman, a Mexican, and a Nigerian. Many were not there for political reasons; some had fled because of various conflicts, often connected with drinking, a few because their relationships with German women were prohibited; of these one such was too “Red East German,” a few were African Americans with white women friends. Some of the British had rejected service in Korea. It was a strange bunch. New arrivals were put up in a hotel, then rooms were found or apartments for families. In general, those who found female partners or wives tended to integrate quite well while single GIs, with no trade and almost no German, and no TV as yet, gathered at various dives or the all-night bar at the train station, thus often missing shifts at their usually low-level jobs, or getting into trouble. One interesting exception was a black American, a trained baker and a boxer, who became a favorite athlete until his age caught up with him. Since he worked regularly and neither smoked nor drank, he had a pleasant apartment on the central square of town, and because he was perhaps the first person of color ever seen in this out-of-the-way town, he often attracted and enjoyed a bunch of happy kids, like the Pied Piper. Though he traveled to matches, the rest of us had only one restriction—not to leave the county without permission. It was a very big county, and since we had as yet little reason to travel this hardly worried us.

After a week or so a job was found for me. I received about 250 marks a month in wages, always paid in cash. Rent for my furnished room was 25 marks a month. Like every working person in the GDR I received a hot lunch, which was the main meal of the day in Germany, for one mark or less, and since I had been given enough clothing, shopping problems bothered me less than those of a sanitary nature. Typically for prewar housing, there was no flush toilet but an indoor privy a half-flight down from my room; the pail of water to flush it had to be constantly refilled. So did the pitcher with basin in my room for washing and shaving. Baths were at a bathhouse. And almost every day power was cut off, always unexpectedly; matches and candles had to be kept handy. Like nearly all homes in those days, my room was heated by a big ceramic oven. That required making a fire every day, a technique with newspaper, kindling, and black coal briquettes, which had to be carried up from the cellar after bringing down the ashes from the day before. The coal had to burn thoroughly, for about an hour, before the oven could be safely screwed shut. I soon gave up and lived for one icy winter in a room heated only on Sundays by my merciful but slightly scornful landlady, who also invited me to join the family for Sunday dinners.

Of course, even for a New Yorker whose family seldom had it easy and almost never lived in a comfortable, roomy apartment, one free of roaches and bugs, life was rather primitive. But I rarely complained or even grumbled about it; I had chosen this path myself and could blame no one, except those distant politicians who passed the McCarran Act.

Then too, at twenty-four, I was very much a devoted young communist. I had not chosen the GDR but I was now here. The aim of the government and ruling party, declared four months before my arrival and proclaimed constantly ever since, was to “build socialism.” That was my aim, too, making me willing to endure growing pains, if that’s what they were, and generally take the bad with the good.

Was there really any good?

My start in this workers’ paradise was helping to tote heavy oak and beech planks at a large factory. This required a long, early walk to work—there were no buses yet—and an equally long, far more tired walk back after work. In those early years there was still a half-day’s work on Saturday. I soon learned to balance one end of a plank on one shoulder while the man in front of me carried his end on the other. It was hard work; I hope they eventually modernized it after I left. In our “brigade” of five men, Jakob, the “brigadier,” received the assignments—how many oak or beech planks were needed—and did the required paper work. Jakob, as a member of the German minority, had been forced to leave his Hungarian home at war’s end. Although I could speak German pretty fluently by then, his accent was at first hard for me to understand. He was an easygoing fellow, however, and we got along well from the start.

There were certainly differences from the two factories I had worked in in Buffalo. There we had to bring our own lunch or run to a diner we called the “Greasy Spoon.” In the factory in Bautzen there was both a breakfast room for the mid-morning break, called “second breakfast,” with as much free ersatz coffee as you wanted; the canteen, run by the union, served the not fancy but quite adequate hot lunch, which always included potatoes with meat or fish and vegetables.

Unlike at the Buffalo factory, in the Bautzen factory there was visible propagandizing, with slogans urging socialism and improved labor effectivity, always in white letters on red cloth, but few paid any attention to them (except me, at first). In general, there and in many factories I visited in later years, I found a rather relaxed atmosphere, perhaps in part because, with every hand needed, no one feared losing their job. In fact, whenever the workload permitted, it was possible to visit a doctor, a dentist, a hairdresser, and even a little cooperative grocery, where now and again some goods were on sale that were not easy to find, if at all, in shops outside the factory. That meant that if the factory grocery offered imported lemons or raisins or fresh, early tomatoes, strawberries, or cherries, a considerable line quickly formed. Work could wait! And that explained what had at first puzzled me: why people came to work not with a lunchbox but with a worn but capacious briefcase.

I think everyone was automatically in the union, but I can hardly recall the union meetings—perhaps my language handicap induced me to skip them. I think everyone, or almost everyone, also felt obliged to pay a few pfennigs in dues as a member of the German-Soviet Friendship Society—even me. I had been moved when the victory of Stalingrad over the Nazi Wehrmacht ten years earlier was marked by a special ceremony in the center of town—in Germany!—but now I think that many of my fellow workers saw the occasion largely as a chance to get home a little earlier than usual with no loss of pay.

A memory note: A workmate, pointing to a big furnace, said, “When Friedrich Flick owned this plant during the war that’s where they threw corpses of foreign workers or prisoners of war. Too many hours, too heavy work and too little to eat.”

A very different but also moving note for me: Seeing a train pull into the station, still using an old steam locomotive, and reading, painted on it in big white letters, “Free the Rosenbergs!”—the Jewish couple facing death in Sing-Sing prison.

My factory job lasted only five months. At that time, before my second winter, I had the greatest luck. I found and fell for my Renate. Coming from a village too far to commute daily, she also had a rented room, nicer than mine. And it was, like her, warm and cozy in the evening.

I SOON DISCOVERED customs that were neither good nor bad, just unusual, even comical. Like the constant handshaking at any and every occasion, such as with every single member of my work team each morning, then all over again at quitting time. Or little girls’ curtseys and boys’ forelock-tossing bows of the head when introduced. Also, the “Guten Tag” and “Auf Wiedersehen” greetings on entering and leaving every grocery or bakery, whether or not anyone was listening. Or the reluctance of young fathers to push a baby carriage and, if there were no escaping it, to do so with one sidewise outstretched hand while looking away, as if the child belonged to someone else. Completely taboo for males in those days was carrying a bouquet of flowers, even if concealed under paper. Later, these taboos disappeared.

Then there were the language problems: the (impossible) need to know whether a noun is masculine, feminine, or neuter and treat it accordingly, which Mark Twain happily satirized by noting that a red beet is a “she” but a pretty girl an “it.” One witty Turkish woman I know of, having the usual trouble with such rulings, asked her teacher why the word for “table” was masculine—“der Tisch.” Looking under one she said, “I don’t see anything masculine about it!” I found that Gift means poison, Mist means manure, a glove is a Handschuh or, almost a desecration, a nipple is a Brustwarze—a “breast wart.” Some words caused visiting Americans fewer blushes than laughs: “Schmuck” meaning jewelry, and the polite wish to patrons driving away after a restaurant meal to have a good trip: “gute Fahrt.”

While improving my German and adjusting to customs, I soon noticed the political tensions in the air, reflecting different directions and varying types of people. Some, most to my liking, were warm-hearted people who rejected everything from the Nazi past and were dedicated to creating a fair socialist society. I also found narrow-minded dogmatists, who spouted clichés, surely believing them, but could hardly grasp basic humane concepts and were all too quick to browbeat those with doubts or “wrong ideas.” I had already met some such people in various political parties in the United States, including my own. Often disarmingly similar were the careerists who could parrot the correct vocabulary but were primarily devoted to advancing personal interests. As everywhere, I guess, there were also slow thinkers and downright idiots. And then there were those who, rarely uttering their views out loud, hated the GDR and any idea of socialism, pined for the rule of West German Chancellor Adenauer, dreamed of retaking provinces they had been forced to leave or had learned little or nothing from the defeat of fascism. But humans are complicated creatures who waver, learn, even alter their views. There was a wide range of mixtures and borderline cases; it was neither simple nor really wise to paste people into one or another pigeon hole.

A key factor in my positive outlook was, of course, finding Renate, then a stenographer-typist in a construction company. Not only did I no longer freeze evenings in my lonely room, hunting and pecking at my newly bought typewriter until my fingers were too cold to function, but now, as spring came upon us, we could enjoy wonderful strolls through shabby but oh-so-romantic cobblestone alleyways in the Old Town, baroque squares, and pathways around the sturdy city walls of this beautiful, thousand-year-old town, perched on cliffs above a swift little river. Together we enjoyed good plays and concerts (a new experience for my village-bred girlfriend) in the fine theater and a memorable candle-lit performance of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio in the magnificent cathedral, one of only three church buildings in all Germany which was half Lutheran, half Roman Catholic, and quite amicably divided by a little fence right down the middle.

3—Hot Times in Germany

Germany, too, was divided, though by no means amicably and not nearly down the middle. In this larger edifice the Federal Republic (FRG) occupied far, far more pews and almost exclusively the better ones. The main sermon preached in its pulpit, aside from demanding the return of lost territories, was about German unity: brothers and sisters in the two states must no longer be separated. But the commandment often evoked, unlike the ten from Mount Sinai, was not carved in stone from the start. The unity problem trod dramatically onto the world stage in June 1948 when Britain, France, and the United States suddenly introduced a new monetary currency in their West German occupation zones and, even more divisively, into the populous political island of West Berlin in the middle of the Soviet Zone. There was no Wall or other barrier then. Anyone could shop in the East or West, so the switch to a new currency immediately threatened to flood the East with old currency, suddenly useless in the West, and thus swiftly wreck the entire Eastern economy. Inevitable countermeasures triggered the Airlift to supply West Berlin with food and fuel.

The belligerent politician and later secretary of state John Foster Dulles revealed, but not very publicly, that it was always possible to cool the situation by agreeing on the currency question, but then explained that, firstly, “The deadlock is of great advantage to the United States for propaganda purposes, secondly, the danger of settling the Berlin dispute resides in the fact that it would then be impossible to avoid facing the problem of a German peace treaty. The United States would then be faced with a Soviet proposal for the withdrawal of all occupation troops and the establishment of a central German government. Frankly I do not know what we would say to that.” (Overseas Writers Association, January 10, 1949, quoted in Democratic German Report, DGR, February 2, 1962, 32.)

He was right. The Berlin Airlift proved immensely advantageous for Cold War political acoustics and a dissonant propaganda disaster for the USSR. It also split Berlin and Germany for over forty years.

This had occurred while I was a student at Harvard and resulted in harsh repercussions for the Progressive Party candidate, Henry Wallace, a campaign in which I was actively engaged. Four years later, in 1952, I arrived in divided Germany as a simple Private 1st Class. But while the U.S. Army was sifting through my political past, present, and possible future, Germany’s past, present, and future were being surveyed by far more important figures, President Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin. On March 10, 1952, Stalin made an unexpected offer to remove Soviet troops and control from East Germany, to support free all-German elections, and to permit unification and full German sovereignty. The offer came with one condition, a result of the Nazis’ near total destruction and virtual genocide in the Soviet Union a decade earlier: Germany must be “free, neutral, and demilitarized” and, like Finland or Austria, in no pacts, Eastern or Western.

The response was a resounding “No!” U.S. policy had long aimed at pumping up West Germany. Its powerful, rebuilt industrial base, strategic location, and top-drawer generals with “Eastern” experience were major chess pieces in the worsening Cold War, or someday in a hot one (which a few firebrands were demanding). As the German-born banker and former Roosevelt adviser, James Warburg, vainly told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on March 28: the Soviet proposal might be a bluff, but it seemed “that our government is afraid to call the bluff for fear that it may not be a bluff at all” and lead to unity. (Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, March 28, 1952.)

To this “No” a loud “Nein!” was added. Chancellor Adenauer also feared such unity, preferring an expanding Western ambience with his two-thirds of Germany bound up in it. Only a few West Germans had the courage to blame him for rebuffing this chance at unification. Instead, in Paris, he signed onto a “European Defense Community” with a large German military component, a plan ditched by the French people two years later. All East German proposals to heal the split were ignored; thus, by 1952, the chips were down. One result was the GDR leaders’ call to move on and build socialism in their corner of the country. That smaller corner where, a few months later, I was to land.

As a foreign newcomer who still read no newspapers and heard no radio, I could hardly comprehend such fateful events. But as 1953 moved along. I could see that something was not okay. Earlier rapid improvements in life were slowing down with signs of going into reverse. Even a breakfast staple of mine, ersatz honey, defied past trends—its price went up, not down.

With hopes of unification giving way to increasing fears of Western annexation attempts, the decision to “build socialism,” a lifelong goal of most East German leaders, now required the rapid buildup of an industry to produce coke, iron, and steel, basics increasingly hard to get from traditional West German sources. It was also seen necessary to counter Western rearmament with GDR armed forces. Both endeavors consumed billions of marks. To pay for them and “clear the decks” politically, a stringent, tough policy was adopted, rough on private businesses and wealthier farmers but also on workers, whose wages were to be tied to stricter norms, or quotas, aimed at increasing productivity without putting too many more inflationary 10- or 20-mark bills into pay envelopes. During my first winter and spring I could sense the growing unhappiness at all of this.

In March 1953, Stalin died. What would that mean for the world, for the USSR, for us in the GDR? We could not peer through the distant thick Kremlin walls and perceive that the new ruling team in Moscow, noting that the economic strategy in the young GDR was not going well at all, had concluded that urgent changes were needed if menacing dangers were to be prevented. They pushed the GDR rulers into a sudden, quick reversal.

On June 11, the New Course was announced, annulling all unpleasant restrictions, cuts, pressures, and many jail sentences, with one important exception. The tighter production norms would remain unchanged. This exception neglected the main cause of anger for the working people who were always hailed as the foundation of the new republic, and so the entire turnaround proved to be too little and too late. On June 16 and 17, first in East Berlin, then in many towns and cities around the GDR, there were demonstrations, stoppages, as well as violence by workers and those who jumped on board with them, including young toughs from West Berlin. A few local official buildings were seized, a Berlin department store was set ablaze, and prisoners were freed, allegedly including virulent Nazi war criminals.

Workers in a railroad coach factory in nearby Görlitz also went on strike for a day or two. In its sister plant in Bautzen, where I had been working seven weeks earlier, little work was done on June 17, but there was no strike. A tiny riot by young men in Bautzen attracted only a handful of workers and ended quickly when a truckload of Soviet soldiers arrived and fired some shots into the air.

There were some casualties elsewhere, but Soviet military involvement, also involving tanks (with orders not to shoot), soon ended the uprising. Historians still argue about whether it was based solely on the resistance of downtrodden workers, as claimed and celebrated to this day, or was fostered by Western propaganda and provocateurs, as GDR media asserted. In my view it was both. Genuinely angry protests reflecting disappointment and frustration were quickly utilized from without, especially in the twisted divided city of Berlin. A key factor was the CIA-financed radio station RIAS (Radio in the American Sector) in West Berlin. Egon Bahr, then RIAS director and later a leading Social Democrat, admitted—or boasted—that though RIAS had not planned or directed it, its broadcasts had acted “as the catalyst of the uprising … without RIAS the uprising would never have taken place in this form.” (Interview with Nana Brink, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, January 9, 2006). Indeed, RIAS broadcast the call for a general strike. The basic goal, it seems clear, was what is now called “regime change,” an early version of the Maidan Square “uprising” in Kiev in 2014 (and many other countries). Most GDR citizens did not take part, but few had been happy in the preceding months.

As for me, since I had left the factory and taken a job as cultural director of a new clubhouse for the thirty or forty Western army deserters then settled in Bautzen, responsible for chess, billiards, and ping-pong tournaments, for outings, dances, films, and such, these events had little effect on me, although I was happy when the price of my artificial honey and other items was reduced and those power stoppages for homes, requiring candles and matches, were finally eliminated.

After six months I quit as cultural director and joined the other deserters in a special one-year apprenticeship in any one of four handicraft skills. Since few had ever learned a non-military trade I found this a clever, wise, and humane idea, with all receiving a generous monthly stipend, more for those with dependents. And to my amazement, I learned how to work a lathe machine.

Before I could test my new skill, however, and perhaps luckily not just for me but for the economy, I got a very different opportunity—to take a four-year course in journalism at Karl Marx University in Leipzig. Although I was already twenty-six, I was only too happy to move from a small town to the GDR’s second-largest city, with a half-million inhabitants and a famous old culture, Johann Sebastian Bach being its main gem, along with Goethe, Schumann, Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, and an annual book fair nearly as old as printed books. Plus, there was a monstrous monument from 1913 celebrating the defeat of Napoleon there in 1813. I had no problem getting accustomed to city life, nor did Renate, now my fiancée, who had found herself a job and a room in Leipzig even before I arrived.

4—Leipzig and Karl Marx University

A year later, we got married. We were assigned a room-and-a-quarter in the apartment of an elderly, by no means welcoming couple. An interest-free 2,000-mark credit for all Bautzen ex-soldiers allowed us to set up a household centered around a big bed and a big desk. Though Renate’s job as stenographer-typist was not well paid, students received scholarships, 180 or 240 marks a month, with possible bonuses, and a small but growing number of foreign students, including me, got 300. After buying our main furniture, no other major purchases were possible, yet we were able to get along quite well without financial worries. My hot meal of the day, as in the Bautzen factory and like Renate’s in her publicly owned wholesale firm, cost a pittance. The New Course in June 1953 ended reparation payments to the USSR and meant a steady increase in the amount and assortment of consumer goods. Once again people looked forward to May Day and the “Day of the Republic” on October 7 when the press had page-long lists of price cuts on food, clothing, and other goods. We bought our groceries in consumer cooperatives or private retail shops, where our ration coupons enabled us to buy meat, milk, butter, and sugar at very low prices. Since rations varied according to one’s job and profession (lowest for non-working seniors), jealousy and not a little bitterness were often involved, but pregnant or nursing mothers received higher rations, and this category soon included Renate! When monthly ration coupons were used up, people could buy all they wanted (and could afford) at the well-stocked but highly priced nationally owned shops called HO (an abbreviation for Retail Organization). Nationally owned restaurants (Gaststätten) added a letter, forming the interesting abbreviation over the entrance: HOG.

When our son was born, we were assigned two rooms and a small kitchen, again within a larger apartment but with a friendlier widow. Everyone had to be housed, no one could be homeless, but since the huge apartment construction projects did not start up for another decade, many, like it or not, had to share their larger apartments.

After our first joy at our unplanned but dearly loved baby we faced the unhappy necessity, first due to Renate’s short illness, then because of our work, of placing him in a weekly nursery for student mothers, fetching him only for weekends. This cost almost nothing but often meant tears on Monday morning. Otherwise we led an untroubled life, always with enough for our Sunday schnitzel, potatoes, mushrooms, and vegetable, plus a self-made plum cake which, lacking an oven, we gave to a bakery on Saturday and fetched fresh and warm on Sunday. We had enough for the movies, the theater, and occasionally the opera. Regular medical and dental care and medicines, a special gymnastics course for expectant mothers, the ambulance and virtually private delivery of little Thomas were all covered by national low-cost insurance, with six weeks paid leave before and eight weeks afterward, which were later greatly increased. Breast-feeding was also rewarded, and homemakers, almost always women, got one free paid “household day” every month. Life was markedly improving, though at uneven rates for different groups and never without a variety of shortages. Disposable diapers and prepared baby food did not arrive until we had our second son, Timothy, six years later, which meant that I did a lot of helping with diaper-washing and squeezing of carrot juice, mashing potatoes, or other baby needs.

Despite all improvements, the conflicting, often hostile, standpoints I had noticed in Bautzen were still quite evident in Leipzig. One flight above us, the widow and daughter of a man executed by the Nazis for his communist underground activity were fully devoted to the GDR. So were a young couple, puppeteers, who lived a flight below us. A young pastor and his wife were clearly if mildly opposed to “this system”; relations between the GDR leadership and the Lutheran Church were at one of their periodic low points. A man on the ground floor, expelled from now Polish Silesia, was violently anti-GDR and often traveled to West Berlin to join in angry rallies, sanctioned by the Western occupation authorities and the West German government, to demand the return of the “lost provinces.” The GDR, in sharp contrast, recognized the new borders and signed friendship treaties with the Communist-led governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia, while its media played down or omitted references to Silesia, East Prussia, Sudetenland, and the other lost areas. Every effort was made to integrate their former inhabitants, never referred to as “refugees” as in the West but as “re-settlers.” Many who rejected such integration moved westward.

The atmosphere at the Journalism School was free of such conflicts. Some students had also been forced to leave “lost homelands,” but I heard no complaints on this issue, certainly not from my roommate, who came, as an orphan, from East Prussia. Nearly all those who chose journalism—and were accepted as students—were pro-GDR; our department wasn’t called the Roter Kloster (Red Cloister) for nothing. It was very different from, say, the Medical School, with its many offspring of doctors, relatively prosperous yet often far from satisfied with socialist medical policies.

From the start, we were apportioned into “seminar groups” of about twenty-five students each, all of whom had the same classes in the first two years and kept together for political meetings, cultural evenings, trips to the movies or a concert, and occasional trips to help clear the last of Leipzig’s rubble, help in the potato or sugar beet harvest, or, in one case, tamp in rail tracks in an open-pit lignite mine (for a week with pay). Of our group, over the four years, two disappeared and moved to the West, a relatively low average in those days.

We in the Red Cloister also noted some variations, beginning with the professors. Two were dyed-in-the-wool dogmatists. The one who taught basic communist theory, “Historical Materialism,” defended every party and government policy up until the very day it was altered—and then defended the new policy just as uncompromisingly. The other, of Romanian-Jewish background, had been a daring left-wing fighter during the First World War and in the Hungarian Revolution of 1919. Forced to flee to the USSR, he had tried to reeducate fascist Romanian, Hungarian, and German prisoners of war during the Second World War. I wondered how successful his efforts had been, for he was no teacher and the students laughed at his weak endeavors. Perhaps he was given the job out of respect for his past.

But our dean, Hermann Budzislavski, who taught German Press History with a stress on progressive journalists, gave dynamic lectures, with constant pacing back and forth and changing of eyeglasses. He was popular with everyone. While a wartime exile in the United States, as a Jewish leftist, he had been an assistant of the famous journalist Dorothy Thompson, the wife of author Sinclair Lewis.

Wieland Herzfelde, who had also found refuge in the United States (and was also Jewish), taught World Literature, with a stress on the classics. He himself was part of German history, having built up and managed the legendary Malik publishing house until 1933. With his famous brother John Heartfield and the great artist Georg Grosz, he had led the German section of the Dada art movement and developed political photomontage, with witty, biting attacks on the Nazis, from whom they escaped in 1933 by the skin of their teeth. The brothers, on arrival in the GDR from Britain and the United States, had been treated with shocking distrust at first; those were the shameful Stalin-motivated years of mistrust of “Western emigrants,” often Jewish. But then Stalin was dead, and so was that evil period, and they soon came to deserved honors. As professor, Herzfelde made high demands, assigning lots and lots of great books to read, but was therefore not so popular with some students.

Most popular was Hedwig Voegt from Hamburg, imprisoned three times for fighting the Nazis, who came to the GDR after the war to study and became an expert on German literature. Her moving lectures inspired admiration and love for many great writers, for me largely unknown till then.

Many professors and administrators had been active anti-fascists. University rector Georg Mayer retained, to my amazement, the ancient title “His Magnificence” and wore the traditional golden chain at ceremonies. But he also joked that as a young fraternity student the titles “Bottle-Mayer,” “Duel Mayer,” and “Bordello-Mayer” had all applied to him. Later I learned that the Nazis had thrown him out of academia for his courageous opposition.

Sadly, two famous anti-fascist professors in other departments proved too independent for GDR leaders. The philosopher Ernst Bloch was dropped from his position in 1957 and left the GDR in 1961; literature scholar Hans Meyer left in 1963. Neither, I believe, ever abandoned his belief in a socialist future.

Those were turbulent times for socialists or communists, with many ups and downs. The uprising of June 17, 1953, caused very unpleasant shake-ups for some near the top but brought not only more consumer goods and an end to rising prices, taxes, and power blackouts but a loosening of many strictures on political discussion. All this thanks in great measure to the new man in Moscow, Nikita Khrushchev, whose “secret speech” in February 1956 detailed immense crimes committed during the Stalin years. (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1956khrushchev-secret1.html) Countless prisoners in the Soviet Union were freed, pressures were reduced, and books written that, in translated editions in the GDR, broke many political taboos. Ilya Ehrenburg’s The Thaw gave the era its name. One unexpected result of this thaw was a brief uprising in Poznan in Poland and a new leadership there under the once-imprisoned and far less dogmatic Wladislaw Gomulka. The always hostile BBC, in its broadcast for the GDR, aired an acerbic joke: A young prisoner asks his older cellmate, “What are you in for?”—“I denounced Gomulka. And you?”—“That’s odd. I’m in for praising him.” Just then a third man is locked into the cell. And why? “I’m Gomulka!”

My marriage after my first college year meant living “off campus,” so I was not so closely involved in “private-level” exchanges. But I couldn’t fail to notice the increase in discussion, often reflecting hopes, like my own, for a far more elastic, realistic approach to our “unbending principles.” This was reflected in our first printed student newspaper. One article reviewed the East Berlin political cabaret Der Distel (The Thistle), which satirized attempts to ignore events in nearby Poland. Another urged that the Leipzig press should also print the critical letters to the editor. My article called for more balanced, less simplistic media reports about the United States. Other articles were also mildly critical; none were “oppositional.”

But the Polish upsets were followed by an uprising in Hungary, with angry workers waging a brief civil war, enthusiastically encouraged by the Catholic Church and Voice of America. Party employees and government employees, including security service agents, were hanged or otherwise killed, and when Soviet tanks moved in there were deaths on all sides. These tragic events caused a crisis in the world’s left-wing movements and also frightened GDR leaders politically and perhaps personally, although, as I heard it, moving their homes out of Berlin to an inaccessible enclave to the north was due less to their fears than to the worries of their security officers. But it was certainly their fears that led to another tightening of screws generally. A second issue of our student newspaper was long in coming—and then tame as a lapdog. Political “deviations” by students, or in one case by a teacher, were harshly castigated. The teacher lost his job, but rather than “proving himself” at some temporary industrial job, as demanded, he too took the option, still open before the Wall, and went west.

And me? I received the U.S.-Communist newspaper Daily Worker, which, after Khrushchev’s speech, had opened its “Letters” pages to an amazingly critical debate. The hot arguments and hot words and my American background made finding my way especially complicated. I wondered whether the constraints on free discussion and one-sidedness in the GDR press were too similar to what I had experienced in the United States. Was this a mirror image of McCarthyism? Could I approve of it?

There was a semi-official rebuttal to such doubts. The pressures in the GDR were actually the opposite of those used by McCarthyites, who aimed at suffocating all efforts at progress for workers and unions, for blacks and women in their fights for equality, and squelching all opposition to the Cold War, or a hot one with atomic weapons. GDR pressures, it was averred, were the opposite—to strengthen a society where working-class youngsters got a free college education, no one was jobless, and everyone was medically insured.

I could not dismiss such a justification out of hand. In the United States, I had experienced the merciless offensive of the powers-that-be against all opposition, most dramatically at Peekskill in 1949, when state troopers supported the goon mobs that threw rocks at us at a concert with Pete Seeger and the great singer and actor Paul Robeson. All the windows in my bus had been shattered, along with any possible illusions. Every dirty, even bloody method was used to silence us. Could I get distressed at countermeasures aimed at stymieing such elements here in this most sensitive spot in the world, where nose cones of opposing atomic missiles faced each other? But were such counter-measures really the most effective method? And what about morality? I had plenty to chew on.

Again, ups followed downs. The atmosphere improved with the flight of Sputnik on October 4, 1957, and recurrent Soviet space successes that followed. Today many are unaware of the alarm in the United States over the triumph in the Eastern bloc. The GDR press was delirious with each new achievement: the Sputnik starting things off; the first animal in space—the dog Laika, who unfortunately could not return; the first human, Yuri Gagarin, who could. Then the first two men together, then three men, the circling, filming, and hitting the moon (but not landing), the first woman in space in June 1963. For the GDR media each new feat was proof of the superiority of socialism. An American sour-grapes comment on this one-upmanship was that “before we send a woman into space the Russians will have sent up the Leningrad Symphony Orchestra.” (Meg Waite Clayton, “Female Astronauts: Breaking the Glass Atmosphere,” Los Angeles Times, June 15, 2013.) Some years later the tables were turned—but very quietly in the GDR.

There was good news closer to home for the GDR. In May 1958 rationing was finally dropped. Instead of a dual price system with cheap ration card staples and all you wanted at higher prices there was now a single-price system, uniform in the whole country, for goods like bakery, butcher, and dairy products. Amazingly—some said unwisely—these new prices stayed firmly frozen for over thirty years, until the end of the GDR.

In September 1958 my four college years came to an end. Some dogmatic aspects had been troubling, but on the whole I had found a friendly, often quite jolly atmosphere among most students, now full of curiosity and expectation as to their future careers. I celebrated with a spaghetti Bolognese feast for the twenty-odd members of my group and directed that the males do the main work, shaping little meatballs, slicing onions and mushrooms. That was totally new for most of them, but a big success. And now I had a second diploma. It was not an M.A., but that never bothered me.

After a happy two-week vacation with Renate and our two-year-old Thomas on the cliffs of “Saxon Switzerland” along the Elbe River, where I had first seen the GDR six years earlier, I landed in Berlin, at first in a rented room on the city outskirts and commuting every weekend to Leipzig.

5—Life in Doubled Berlin

What a different world I found! Though not like the picture of East Berlin so often conjured up with nothing but military parades, cloak-and-dagger Stasi men snooping everywhere and long lines of angry customers, it was nevertheless a highly unusual town, with countless complexities.

This was before the Berlin Wall; people moved back and forth between East and West through that strange open door in the Iron Curtain. And did they ever move back and forth! Bonn and Washington, with sights set on impressing and winning people in East Berlin and the GDR, used West Berlin as a magic magnet, pouring in billions to repair war damage, renovate older buildings, build new ones and, by slashing taxes, attract lots of industry and fine shops with quantities of fancy goods. One symbol was the KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens) department store with a legendary assortment of delicacies. Closing times for nightclubs, bars, and dance-halls were eliminated, and well-subsidized cultural events were offered for every taste, with the desired effect on large numbers of Easterners. U.S. culture, from bebop and theater of the absurd to Disney and dungarees, all of it attractive, swamped West Germany and, just as intended, spilled over eastward in great quantity, if not always quality.

The existence of two currencies had strange effects unknown to the Western world. Many East Berliners commuted to West Berlin, happily undercutting wage levels there. Measly 200 West-marks were magically transformed by the many Western money-changing offices into 800 or more GDR marks—the rate changed daily. An untrained East Berliner, perhaps a cleaning woman, could return eastward on payday with more in her purse than a highly trained GDR engineer. Many such commuters bought butter, a large sausage, or a dozen eggs at low East Berlin prices, sneaked them across in the subway or el under their coats and sold them to West Berliners at well under the going price. Translating this into GDR marks meant a nice additional source of income. A woeful story about hard times in the East might also get a sympathetic gift from an employer, maybe a pack or two of Luckies or Camels that could be sold for a stiff price back in East Berlin. With 50,000 to 80,000 commuters it certainly worsened a perpetual East Berlin lack of labor power.

For many, smuggling was part of everyday life. At the last station before crossing into West Berlin, two GDR customs men walked through the el or subway cars and collared some who were all too conspicuous, perhaps a middle-aged or elderly woman looking strangely pregnant. They could hardly control such butter-eggs-sausage smuggling; their trained eyes were keener to catch professional smugglers of valuable GDR products like cameras, children’s goods, or Meissen (that is, Dresden) chinaware.

The two currencies caused endless problems. The largely artificial 4:1 or 5:1 exchange rate led many West Berliners to cross over for themselves and buy groceries in East Berlin at dirt-cheap prices, thus helping to empty the not so heavily laden East Berlin shelves. This was then prevented; a show of ID was demanded (which all Germans possessed) to prove GDR identity for every purchase, even an ice-cream cone or a bockwurst (a hot dog equivalent). Though an awful bother, most East Berliners agreed with this and wished that ID also be required for services like beauty parlors and physical therapists. It wasn’t, and those businesses near the sector borders were full of crossover West Berlin customers using West-marks or West cigarettes as bribes to avoid waiting and get the best treatment at a very low price.

Along the west side of the zigzag border, glittering movie theaters lured East Berlin kids to Hollywood cowboy or gangster films with special low ticket prices to overcome the currency disadvantage. Superman-type comic books were sold to them at cut-rate prices. East Berlin adults crossed over to see Hollywood and West German films, good and not so good; one hit was Kazan’s On the Waterfront. Highbrow crossovers went to West Berlin theaters to see dramas then popular in the Western world. I soon realized that most East Berliners did cross over, whether commuting to a West Berlin job then spending a Saturday night dancing or at a show, or purchasing items, modern, fashionable, or simply in short supply in the GDR. East Berlin, despite constant improvement and a better assortment of goods than elsewhere in the GDR, could never keep pace with the enticing offerings of a Marshall Plan—subsidized, booming capitalist economy just a few streets away.

As I mentioned, this migration was not entirely one-sided. Excluded from ID requirements in East Berlin besides hairdressers and physical therapists were books, records, and theater tickets, already extremely inexpensive. Even opera tickets cost only 15 East-marks. Thanks to the exchange rate, this meant that West Berliners, for the best seats in the East, paid little more than they would for a serving of coffee and cake, making it harder for us East Berliners to get good seats, or sometimes any at all. But it was well worth the effort, as I will soon describe.

Berlin, already split before the Wall, had its amusing features. At one corner in downtown East Berlin you could look north and read the GDR version of the evening news in rotating electric letters at Friedrichstrasse Station. If you turned your head 90 degrees westward you could read a very contrary CIA version rotating from a tall RIAS radio tower in West Berlin.

A few subway lines moved from one West Berlin borough to another, crossing through a part of East Berlin and stopping at stations there. So for some stretches passengers were mixed. I enjoyed seeing one passenger reading about evil drugs and joblessness in the West while another, sitting peacefully next to him, read about the hunger and oppression in the Soviet Zone he was passing through.

I watched West Berlin loudspeaker trucks drive right up to the unguarded borderline, loudly blaring anti-GDR messages. As soon as possible, a sound truck arrived on the Eastern side and, almost bumper to bumper, blasted loud music to drown it out until it drove off to the next location.

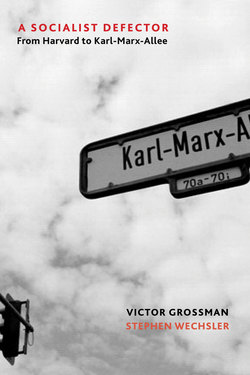

As for me, fearful of somehow being recognized or simply asked to identify myself, if only as witness to some accident, I never risked putting one toe across a border marked only by the famous signposts “You are now leaving the American (or British or French) Sector.” I was also a bit nervous since the street where, after a year, we got a new little apartment that was separated from the U.S. sector only by unlighted gardens. I was doubly glad when, after a lucky swap, we got a centrally heated apartment in the very safe Stalin Allee, which, happily, five months after we moved there, was renamed Karl-Marx-Allee.

6—Berlin’s Cultural Scene

Renate and I were not greatly tempted by the goodies across the dividing line (and we did get a few goodies from my parents). The stage and the opera, which we had greatly enjoyed in Bautzen and Leipzig, meant more to us. Despite fantastically low prices, the quality in East Berlin was superb.

The first play after the war, in September 1945 in East Berlin, had been Gottfried Lessing’s 1779 classic Nathan the Wise, a call for tolerance between religions, a vigorous rejection of anti-Semitism and fully taboo in the Nazi years. Those first audiences, huddled in the unheated auditorium of the famous Deutsches Theater, often physically hungry, were also hungry for cultural fresh air. Its producer, Gustav von Wangenheim, a communist theater man, had fled from the Nazis to the USSR and during the war called on German soldiers at the front to lay down their arms. Then he taught German POWs at the “anti-fascist schools.” The Nazis had sentenced him to death in absentia. His response was Nathan the Wise, four months after their defeat. His second production was Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, its Berlin premiere and first introduction to recent American drama.

Similar sentiments motivated many people of stage, screen, and the arts who came out of hiding, literally or figuratively, or returned from exile in a dozen countries. Von Wangenheim was followed by Wolfgang Langhoff, arrested by the Nazis the night of the Reichstag fire in 1933, tortured and sent to toil as one of the “peat bog soldiers,” prisoners made famous by their song, which, after his release and flight to Switzerland, he had edited and publicized. His first great success was Goethe’s Faust and even more an adaptation of Aristophanes’ ancient comedy Peace by the brilliant writer Peter Hacks, newly arrived from West Germany. At the premiere the ovation lasted three-quarters of an hour, the stage “iron curtain” had to be raised fifteen times!

The manager of the wrecked and rebuilt Volksbühne (People’s Stage) was Fritz Wisten, also a leftist, and Jewish, arrested and mistreated by the Nazis but saved from deportation and death because his actress wife was Aryan. They were even able to conceal and rescue a few colleagues from the Jewish Cultural Association that he had once headed. At the Volksbühne, we enjoyed jolly but still hard-hitting plays by old Molière from seventeenth-century France.

Most of all I loved the Brecht theater. The great Bertolt Brecht arrived in Berlin in 1948 with his wife, Helene Weigel, forced to flee his exile home in California by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Neither Switzerland nor Austria offered him a chance to produce his plays, but then East Berlin gave his new Berliner Ensemble the same beautiful, baroque theater where his Three-Penny Opera had triumphed in 1928. The first production was his play Mother Courage, about a woman who sells goods to soldiers during the Thirty Years War (1618–1648) and, despite one tragic loss after another, never comprehends that war is never good for “little people” like her. The role, wonderfully played by his wife, was an early source of controversy. Mother Courage was far from the “socialist hero” type often sought in those years. It was really hard to identify with her. Brecht did not want audiences to “identify,” however, but to reflect and draw their own conclusions; most in the audience had also been forced to learn that war brought nothing but misery and ruins. Mother Courage’s run-down little wagon circling at center stage became a legend.

Co-starring with Weigel, and even more legendary, was the actor and singer Ernst Busch. The Spanish Civil War songs he recorded during the fascist bombing of Barcelona in 1938, based on the international song book he compiled, are still loved in many countries. After Spain’s defeat, he was turned over to the Gestapo and narrowly escaped death when the penitentiary was bombed. Now, defying partial facial laming, he triumphed again and again, once again with the song “Mackie Messer” (“Mack the Knife”) from The Three-Penny Opera and above all in the title role in The Life of Galileo. Every production in the Brecht theater was noteworthy, unique—and a treat.

And then there was opera, far more popular here than in the United States. The State Opera House on Unter den Linden boulevard, built for King Frederick II (Frederick the Great), whose classical lines made it my favorite building, was managed by Max Burkhardt, who had spent six years behind bars, partly in solitary confinement, and also survived only because his wife, thanks to false documents, was an Aryan. I recall Shostakovich’s The Nose, not only its music and absurdly funny plot, but because our balcony seats were five meters from the loge where Party head Walter Ulbricht was also enjoying the premiere. Also, in Tosca, otherwise done beautifully, I recall how the heroic tenor Cavaradossi’s can of paint defied stage directions by falling from its scaffold position and rolling slowly downward, with all eyes on it except those of the oblivious hero, till it fell into the orchestra. Best of all was the jolly Barber of Seville, a production so appealing with its ironic charm that it is still being offered.

Good as the State Opera House was, the rival Komische Oper (Comic Opera), headed by the great Austrian Walter Felsenstein, was even better. It featured no world-famous singers, just very good ones who could also act. Felsenstein and his team rehearsed even the smallest roles for months till they attained, for us, perfection. Every performance was a true delight, from the eerie cellar and riotous court in Offenbach’s Barbe-Bleue or Bluebeard to the overwhelming gale and heart-rending ending in Verdi’s Otello, to Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen, which even delighted Renate’s parents, no opera-goers, with its jolly barnyard full of chickens, its forest with wonderful birds and animals played by children, and the melancholy arias of love and aging in a Slovak tavern. They were all unforgettable.

For those who liked operettas or an occasional musical there was the Metropol Theater, and for revues, chorus lines, and big circus shows the Friedrichstadt Palast. I come later to political cabaret.

Indeed, East Berlin had oodles to offer in the cultural field. In 1959 West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt, a Social Democrat, speaking to an American TV interviewer about the GDR, said that “to live under communism would be worse than an atomic war.” And yet, as one living “under communism” in this so horrible land, I found that its theater and opera, which matched any in Europe, offered at least a few compensations of which Willy Brandt was perhaps unaware.

7—Filmmakers and Other Anti-Fascists

Renate and I saw more movies than plays and operas, of course, and both Eastern and Western films were always a frequent subject of discussion, critical or admiring. The GDR’s one film company, DEFA, was often the center of debate.

East Germany was well ahead in reviving postwar movie-making, aided by Soviet advisers like Lt. Col. Alexander Dymschitz, an expert on German culture who supported many first steps in a new cultural life. In November 1945, a group of writers and filmmakers, former emigrants and some who had remained but had never been Nazis, discussed possible plans. As Paul Wandel, the head of the group, recalled: “When we first met in the wrecked Hotel Adlon to discuss the future of German film, most of those present doubted whether there was any point to it at all.” (Stephen Brockman, A Critical History of German Film, Rochester: Camden House, 2010, 188–89). Conditions were abysmal; the first director once asked his assistant to find a little butter so he could stay on his feet. But, they concluded, “Film today must offer answers to our people’s basic questions.” And so DEFA was founded.

Its first task was tackling questions about fascism. Within a year, the first postwar German film, The Murderers Are Amongst Us, warned that men guilty of war crimes were already regaining wealth and influence. This film, which started the world career of the fine actress Hildegard Knef, was followed in 1947 by Marriage in the Shadows, a poignant yet hard-hitting tragedy about Hitler’s genocide against Jews. Eleven million tickets were sold, mostly in East Germany; nearly every adult must have seen it, a factor of great importance in combating Nazi ideology. A year later The Blum Affair laid bare the roots of anti-Semitism before 1933. Such anti-fascist films, among DEFA’s best, some real masterpieces, were almost completely ignored or boycotted west of the Elbe and abroad.

Instead, West Germany was inundated with two hundred Hollywood films a year plus dubious pre-1945 German revivals. When filming was finally begun, wartime rubble was occasionally shown, but, for years, almost nothing about the reasons for it. Romances on happy Alpine slopes and meadows were frequent, at times with the same directors who once produced rabid Nazi films.

In all cultural fields the prevailing atmosphere in East Berlin was unambiguously anti-fascist. The first head of the artists’ association, Otto Nagel, had been thrown out of a leadership position by the Nazis in 1933, imprisoned in Sachsenhausen, then released with a strict ban on painting even at home. His successor was Leah Grundig, arrested by the Nazis but able to emigrate to Palestine (there was no Israel then). Her husband, Hans, also a noted artist, was first imprisoned, then sent on suicide missions into battle on the Eastern Front, where he deserted. The writers’ association was headed first by a writer who had fought the fascists in Spain, then by Anna Seghers, an exile in France, Cuba, and then Mexico, whose anti-Nazi novel The Seventh Cross was filmed with Spencer Tracy in Hollywood.

The composers elected a president who had not been an anti-fascist but was no Nazi, just a good composer, and the composers’ secretary-general at his side had been active in the Dutch underground resistance. The dean of East Berlin’s musical conservatory, Eberhard Rebling, after an amazing escape from a Nazi police van, had also been active in the underground in Amsterdam.

The leading cultural organization, the Academy of Arts, was similar. Its first chosen chair was Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann’s brother, whose novel, filmed as The Blue Angel, had made Marlene Dietrich a star, died just before leaving his California exile. The equally famous novelist Arnold Zweig came from exile in Palestine to replace him, followed by the exiled poet Johannes R. Becher, author Willi Bredel, a veteran of Nazi prisons and front action in the Spanish Civil War, and Konrad Wolf, who had been a young lieutenant in the Red Army and later a master film director—in my eyes one of the very greatest. His father was a world-famous writer, Friedrich Wolf, his brother was the master spy chief Markus Wolf, the East German–Jewish counterpart to Bonn’s ex-Nazi general, Reinhard Gehlen.

8—Democratic German Report

After four months working at Seven Seas Books, which published books in English by leftists whose views hampered or prevented sales in their home countries, I became an assistant at Democratic German Report, a biweekly bulletin financed by the GDR. Its masterful English editor, John Peet, twice wounded in Spain, had been Reuters correspondent in Vienna, Warsaw, and West Berlin until, at a sensational press conference in 1951, he accused Reuters and the British press of distorting news from the east and moved to the GDR.

The bulletin reported positively on the GDR but not in the simplistic tones so common in Eastern Bloc publications. He loved wit and irony and liked to quote insipid reports by “daring” Western journalists, who, the minute they risked stepping into East Berlin, found that the sun stopped shining and everyone looked glum. Some incidents were far from glum. One of our readers, an English shop steward touring Eastern Europe by bike, had faced a dilemma at the West-East German border. Western citizens could drive the 120 kilometers through GDR territory to West Berlin, but only on the Autobahn, where bicycling was forbidden. Everyone looked worried until a bright driver put the bike on his truck and told the jolly Englishman, with ragged shorts and a big handlebar mustache, to hop in. In West Berlin he set up his pup tent near the Reichstag. When the police chased him away at dawn, he came to us for help. John Peet called the international office of the GDR labor federation: “We have a British union official here. Can you arrange accommodations?” With high political expectations, they reserved their fanciest guest suite. I must give credit where it is due: the official who came to fetch him with a big car hid any surprise at seeing our somewhat scruffy shop steward, and brought him and his bike to the suite without a word of disappointment.

Since Peet hated travel, I drove around and wrote reports on what I found. At the factory complex where the GDR’s legendary little Trabant cars were made, looking for an interview with a worker, not an official, I picked at random a friendly-looking man making car seats (who turned out to be a rare Baptist church member). He agreed to talk to me and was given a twenty-minute (paid) break. Without a trace of tact, I asked him mercilessly about his earnings, his home, how many suits, coats, and shoes he and his wife owned, about summer vacation trips and the like, and reported it exactly in my article. (Allen Mann [pseudonym of Victor Grossman], “Meet Herr Mueller: GDR Car-Worker,” Democratic German Report (hereinafter DGR), March 3, 1961, 37–39.)

Two months later we had another visitor from London, a young bus driver, his little daughter, and pregnant wife. After reading my report, they wanted to move to the GDR. The husband said, “I don’t have three suits or two overcoats, just one each”; and the woman added, “When could we ever afford a vacation trip?” Their immigration attempt, certainly unwise and officially more than difficult (they spoke not a word of German), ended when the wife became ill and they had to return to London. The episode gave me new food for thought about comparisons—in all directions.

So did my trip to the huge Ernst Thälmann Works in Magdeburg, with its 30,000 employees. I was impressed by its kindergartens and bookshop, its clinic with a medical staff of ninety, and all outpatient facilities. Krupp, its pre-1945 owner, had offered a total of two nurses. I learned of the good contact between a work team I visited and the 9th-grade school class that joined them biweekly, in line with school curriculum, to gain simple skills and learn of factory life. Some Sundays they played soccer together. I noted a sign hanging from the ceiling in one work hall: “Our factory library has thousands of books. How many have you already read?” And in another hall, even bigger: “Our work team saw Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and enjoyed Gerhart Hauptmann’s The Beaver Coat. When were you last at the theater? When are you going again?” With the GDR’s demise this modern complex was split up and sold to five short-lived private firms. Little but empty ruins remain. (Allen Mann [VG], “A Krupp Factory Under Socialism,” DGR, October 14, 1960, 166–67)

9—Nazis and Anti-Nazis

A major aim of DGR was to expose former Nazis still in leadership in West Germany, where the major parties eloquently praised democracy and free elections so long as all those taking part had basically similar goals. But one with very different goals, the Communist Party, was forbidden in 1956, its publications shut down and its leaders arrested. A second rule, quickly learned, was that entrée into the Western community of nations could be achieved by paying compensation to Jewish survivors (if in the West) and, after its birth, paying restitution to Israel and suppressing any and all criticism of its policies. Behind this libertarian “rebirth” and its “economic miracle,” I found that the praise of West Germany for turning over a new leaf was based on well-packaged lies.

Many in the West hated fascism and wanted to create a better Germany. Some U.S. and British officers who themselves fought the Nazis were able to get some of the biggest and worst hanged or locked up, and General Dwight Eisenhower declared shortly after war’s end that National Socialists were nowhere “indispensable.” But many were mysteriously spirited away to South America or Washington, and before long U.S. and British policy was altered. By 1947, with the Soviets no longer seen as allies but as foes, German industrial know-how and military skills were very desirable. In what was called “de-Nazification,” those investigated sought good buddies who testified, perhaps in expectation of return assistance, that they had simply been oh-so-unwilling cogs in all the repression and mass murder and had on one occasion actually helped some Jewish friend or family to get away, or at least expressed a desire to do so. Only a very few unlucky leopards with too many guilty spots, or too few buddies, lost jobs or spent a couple of easy years in prison before being amnestied, to resume their hunt for prey.

A great help in climbing back up was an addendum to Article 131, passed unanimously by the first Bundestag in 1951, which permitted, indeed required, government institutions to fill at least 20 percent of their staffs with people employed there before May 1945, no lower than in their former rank, and excluding only a few who were officially ruled guilty. Full pensions were guaranteed to retirees. For several hundred thousand that meant it was back again to their former elevated status. (Timothy Scott Brown, “West Germany and the Global Sixties: The Anti-Authoritarian Revolt, 1962–1978,” in Basic Law. i.e. Grundgesetz, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 93.)

10—Diplomats

Our eight-page Democratic German Report, to help spoil their return, put facts from GDR research sources into good English and mailed them to all British Labour MPs and many journalists. In 1962 we had our biggest coup, headlined “THE PLAGUE.” (DGR, January 19, 1962, 17–21; March 16, 1962, 20; April 13, 1962, 76; and May 11, 1962, 87.) On a world map we placed a swastika on every country where the West German ambassador had belonged to the Nazi Party. Over fifty were splattered from Santiago to Stockholm, from Washington to Wellington. We added membership numbers and a few details: in 1943 Dr. Ernst-Günther Mohr, then legation counselor, boasted to Berlin that “after 11 months the de-Judification of the Netherlands is almost three-quarters completed.” In 1962 he was ambassador to Switzerland. Our story, often with the map, was picked up in twenty countries, but in West Germany not for two months. Then Der Spiegel finally risked a brief mention, and was promptly, angrily accused by the influential paper Christ und Welt of repeating propaganda from an “obscure and clumsy propaganda sheet,” Peet noted maliciously that neither publication denied a single one of the facts and that the editor of Christ und Welt had himself been a leading Nazi propagandist and SS captain. Dr. Mohr was soon removed, then sent as ambassador to safely fascistic Argentina. (“Berlin Notebook,” DGR, April 13, 1962, 76.)

The West German government tried to respond to jabs and attacks, mostly from Britain, often thanks to facts from our Democratic German Report. They insisted that there were no alternatives and that the GDR leadership was also loaded with Nazis. Bonn’s media connections guaranteed this campaign no little success, above all in the United States, where many accepted West Germany’s voluble regret for past sins and its assertions that East Germany had no regrets for them.

UNTIL THE MID-1970s, thanks to Bonn’s pressure, the GDR was recognized by few countries outside the Eastern Bloc and thus needed few ambassadors. But who were they?

The first GDR ambassador to Poland, with the delicate task of breaking political ice and anti-German feelings, was the famous author and medical doctor Friedrich Wolf, whose taboo-breaking play and film Zyankali (Cyanide), a moving appeal for abortion rights, had shaken up pre-Hitler Germany. Wolf, a Jewish anti-Nazi, had to flee in 1933. His Professor Mamlock, perhaps the first major work about what was to become the Holocaust, premiered in 1934 at Warsaw’s Yiddish Art Theater, then in Tel Aviv, New York, Moscow, and around the non-fascist world. It was filmed in the USSR in 1938 and again in 1961 in the GDR (directed by his son Konrad Wolf).

His successor in Warsaw was Stefan Heymann, who survived Dachau, Auschwitz, and Buchenwald. As the political situation in Poland grew stormier he was followed by Josef Hegen, known as a hard-liner, perhaps as a result of his past. After fleeing to the USSR and working as a machinist until the war, he parachuted behind Nazi lines, fought as a partisan in Poland till he was captured and sent to Mauthausen concentration camp.

An ambassador to North Vietnam was Eduard Claudius. A mason by trade and active union leader, later a writer, he fled the Nazis and was one of the first to volunteer in Spain. He was wounded, then interned in France and Switzerland where Hermann Hesse helped save him from deportation to Germany. When released, he joined the Garibaldi partisans fighting the Nazis in Italy and later became a popular author in the GDR and, briefly, a diplomat.

Almost all those first ambassadors had been Communists-in-exile, fought in Spain or the Resistance, or been imprisoned. One spent seven years in solitary confinement. Another was one of the “peat bog soldiers” made famous by the great song. One man was beaten so viciously by stormtroopers that he lost an eye. Most were of working-class origin; they had to learn on the job to be diplomats. Not one had been in the fascist Foreign Service. Adenauer once replied to criticism on his appointments: “One cannot build up a Foreign Ministry without giving leading positions to persons with past experience.” The obvious question is: Okay, but what kind of experience? (Hennig Köhler, Adenauer: Politische Biographie, Berlin: Propyläen, 1994, 971–74.)

11—School Days

Schools were even more important than diplomats, and Hitler had paid great attention to them. Most teachers were in the Nazi Party. Renate shuddered at any thought of their brutally sadistic ways.

The French and British armies in West Germany showed relatively little interest in the matter. The Americans did; things were at first tough in the U.S. Zone: 11,310 Nazi-era teachers were dismissed. Then came the big anti-Soviet emphasis and resultant appeasement. In Bavaria, for example, 1,800 fired teachers had been pensioned off or had moved away or died. But 8,820 were back in their schoolrooms by 1951, using textbooks that often skirted any analysis or rejection of the Nazi era. The main labor union newspaper, examining West German schoolbooks in 1960, wrote: “There are even history books which deal with the persecution of the Jews in only one line. The average lies between 8 lines and 15 lines.” (Welt der Arbeit No. 9, 1960, quoted in DGR Notebook, August 31, 1960, 148.)