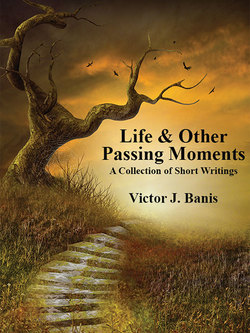

Читать книгу Life & Other Passing Moments - Victor J. Banis - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWELCOME TO ANTOINETTE’S

“You’ll have to go now, Victor,” the woman behind the counter said. “I’ve got to close up.”

He had been staring at a print on the coffee house wall: a Thomas Kincaid inn, mullioned windows, pink and white flowers lining the walk, and an aproned woman smiling beatifically from the open doorway. “Welcome to Antoinette’s,” the plaque at the bottom said.

“Sure,” he said, and drained the last of the long-cold coffee from the bottom of the paper cup, hoping maybe she would offer a free refill, but without much hope. She hadn’t even charged him for the original fill.

He realized belatedly that she had called him by name. Did he know her? He glanced over to where she was busy filling a paper bag with rolls from the shelves. She looked familiar—but he was too hungry, and too tired. His memory had gone to sleep while he struggled to keep body awake.

“Here.” She came from behind the counter and set the paper bag on the table in front of him. “It’s the old rolls, they’ll just throw them out when they open after Christmas. There’s no point in their going to waste. And a panino someone forgot to pick up.”

“Do I know you?” he asked.

“Well, you’ve been sitting here long enough, we could be old friends.” She smiled. “It’s Karen. Karen Delvecchio.”

Which rang no bells in his benumbed mind. “Thanks,” he said, setting the bag on his lap, as if she might change her mind and try to take it back.

She saw him glance again at the print of Antoinette’s. “Maybe you should be looking at that one instead,” she said, indicating the print that hung near the register. He knew which one she meant. There was a birdhouse, in an intense blue, and in the foreground, a large brown bird, holding a glass bottle in his feet, and inside the bottle, what appeared to be a note. There were other bottles, too, floating in a stream at the bottom of the picture. “Heavenly Messages,” it was titled.

“I don’t get that one,” he said, getting up and slipping into the light windbreaker, and donning the thick blue parka over that. The temperature outside had been hovering at about twenty degrees earlier; by now, it was probably more like zero. “I don’t know what it means.”

“Maybe that’s what it means,” she said. “Maybe Heavenly messages aren’t supposed to be writ large, so we can take them in at a casual glance. Maybe we’re supposed to have to work on them.”

He shrugged. “Maybe. I like Antoinette’s better, though. A cozy little restaurant. Warm food, a fire burning. Nothing to puzzle over.” He started toward the front door.

“Wait, here,” she said. She dipped her hand into the tip jar on the counter and pulled out a handful of bills, and thrust them at him.

“What’s this?” he asked, staring stupidly at the money.

She gave him a pale smile. “Maybe it’s one of Heaven’s messages,” she said. “Merry Christmas.”

He knew he ought to say the same back to her, but the words wouldn’t come. Merry Christmas? Nothing merry about it, that he could see.

“Goodnight,” he said instead, and went out. He heard her lock the door after him, eager to go home, to spend the rest of Christmas Eve with her family. He couldn’t blame her. It wasn’t her fault he didn’t have a home to go to, or a family to share it with. The sign said they closed at eight o’clock tonight, and it was after ten now. She had stayed late as it was, to let him nurse that free coffee, and put off the inevitable. He knew that he ought to be grateful, but the gratitude was sour in his mouth.

The inevitable was colder even than he had anticipated. It had begun to snow, and a devilish wind spit the snow in his face and seemed to slice right through the parka. He didn’t have gloves, and it was too cold to carry the paper bag of rolls barehanded. He tucked it inside the parka, and looked at the bills she had handed him. All ones, eleven of them. He shoved them and his hands into his pockets, and thought, I could get something hot to eat, if anything’s open. The Seven Eleven, maybe? Or, better yet, there were the tacky motels on the edge of town. Maybe he could persuade a night clerk to let him have a room for the night on the cheap. Hey, it was Christmas Eve, wasn’t it, as everyone kept reminding him?

He veered off in the direction of Winchester, cutting through the deserted mall. The night was preternaturally still. The steakhouse next door was closed, and the Office Max across the street. Everything was closed; everyone was at home, or hurrying to get there in the lone car that suddenly loomed out of the darkness. On an impulse, he stuck out his thumb, but they whizzed by as if they hadn’t seen him at all, the tires splashing wet snow across the tops of his shoes.

Not quite everyone was home, as it turned out. He saw someone sitting on the curb a few feet away, and slowed his steps. These days you had to be chary of strangers at night, even on Christmas Eve night. The bad guys didn’t take holidays off.

It was an old man, though; he certainly did not look a threat. What he looked, was wracked with despair—and cold—he was in his shirtsleeves, despite the bitter cold.

Victor hesitated, thinking he would slip on by, hopefully unnoticed. But the slump in the old man’s shoulders...and, when he got closer, he could hear that he was crying, great heaves that shook his body and sounded like the muffled wail of a coyote in the silent night.

“Are you okay?” Victor asked, coming closer.

“Okay? Now there’s a laugh,” the old man said without looking at him. “The damn bastards! They took everything. Took my coat, took the few pennies I had in my pocket, took my pint of Jack. Everything. And on Christmas Eve, too.”

“You were mugged?”

“Three of them, their damned britches hanging halfway down their butts. Little punks. If I’d been twenty years younger....”

What could he say? He was no stranger himself to life’s misfortunes. Still.... “What are you going to do?”

“Do? What can I do? Sit here and cuss, is all I can see.”

“You’ll freeze to death. It must be close to zero by now.”

The old man did look at him then. He stared, stared in particular at the blue parka, as if judging its warmth. Victor felt its woolen bulk seem of a sudden to weigh heavily upon him. Automatically, he pulled it closer about himself, asserting his ownership. The old man saw the gesture, and shrugged, and put his head in his hands. There was blood on his cheek, apparently where someone had struck him.

Damn. “Here,” Victor said aloud, unfastening the buttons with numb fingers. He slipped the coat off, and thrust it at the man. “Take this.”

“Just means you’ll freeze to death instead of me,” the old man said, but he took the coat, and hurriedly slipped his arms into the sleeves.

“No, I’ve got this windbreaker, see, it’s warmer than it looks, actually. And some other stuff under it, it’s what they call layering. To be honest, I was thinking about taking the coat off, anyway, it was almost too warm.”

The old man got the coat buttoned. He stood up, brushing snow of the seat of his pants. If he recognized the lies, he chose to ignore them.

“Glad to have it,” he said.

“You could still freeze,” Victor said.

“I know a place,” was all he said. He started to walk, back the way Victor had come. He had gone about twenty feet before he looked back and said, “Merry Christmas.” He disappeared into the darkness and the swirling snow.

Merry Christmas, again. Why did people say that, when there was so clearly nothing merry about it? You’d think they would choke on the words. You’d think that old guy in particular would choke trying to get them out.

He put his head down and began to walk again, in the opposite direction, shivering in the light windbreaker and cursing himself. What a damned fool thing to do. The old man was right, he would probably be the one now to freeze to death, unless he could make it to one of those motels, persuade somebody to make Christmas merry instead of just wishing it.

He plodded through the snow, the bag of food under his arm, hands deep in the pocket of his trousers, half frozen already, trying to think of things to distract himself.

He thought of his mother. What would she say now? He pictured her now, that little woman who had looked so frail, and been so tough. You had to be tough, to raise twelve children with an abusive husband and scarcely a penny to your name.

Lift one foot up, put it down, lift the other, that was how you got where you wanted to go. He remembered her saying that. He lifted his foot, counted: one, two, three....

He had his head down against the wind, so he almost didn’t see the car, sitting half off the road, until the man swung the door open as he was passing, and said, “Excuse me, sir, I wonder if I could ask you something?”

Victor jumped, startled, and took a quick step backward, his foot sliding in the snow, so that he almost fell.

“What the hell?” he swore aloud, his arms windmilling to keep his balance.

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to scare you,” the stranger said. He was short, and thin, and needed a shave, and his clothes looked like he had been sleeping in them. “It’s just, my family and me, we got stuck, we were on our way to my wife’s family, for Christmas, only we run out of gas, and we got no money, and I was wondering if you could spare a dollar or two?”

Victor’s fingers automatically clenched the wad of ones in his pocket. “No, I got nothing,” he said. “Sorry.”

“That’s okay,” the man said resignedly. “It’s hard times, ain’t it?” He turned back to the car, and then looked at Victor again. “You look powerful cold, in just that little jacket. Maybe you ought to sit here in the car with us for a spell. There’s no heat, except from our bodies, but it’s out of the wind, at least.”

“No, I,” Victor started to say, but a fierce gust of wind swept over him just then, seemed to go right through him. How far was it to those motels, anyway? A mile? Two miles. Maybe a rest would do him good.

“Yes,” he said instead. “I’d be grateful.”

“Glad to share what we can,” the man said. He opened the back door for Victor to slide inside. A small boy sat in the far corner, eyeing him warily as he got in. The man got into the front seat, behind the wheel and closed his door. There was a woman in the front seat, too. It was eerily quiet inside, as if they had shut out not just the wind, but the sound of it, too.

“My name’s Don.” He offered his hand across the seatback and Victor shook it. “Mine’s Victor,” he said.

“This is my wife, Ellie, and that’s our boy, Robbie.” The wife nodded and smiled wanly at him. The boy only continued to stare at him from his dark corner.

“Where were you headed?” Victor asked, more to make conversation than because he really cared.

“Pennsylvania,” Don said. “My wife’s mom, she’s got a farm there, told us we could live with her a bit if we could make it there. We started out yesterday, figured we had enough for the gas, but then a tire went, and we had no spare, so we had to replace that, and there went the last of our gas money. It’s a good sixty miles or more yet. I could probably make it, walking, but Ellie, she’s expecting, she’d never make it, nor the boy, and I can’t just leave them here.”

Victor saw the boy’s crutch, then, shoved into the corner behind him, and he looked down at the one shriveled leg. No, of course, you couldn’t walk sixty miles on a crutch, with one bad leg.

The boy—Robbie, was that it?—saw him glance at the crutch and gave him back a scornful look. “Daddy, I’m hungry,” he said.

“I know, son, I know,” Don said. “We’ll just have to wait until...well, we’ll just have to wait, is all.”

“I’ve got some food,” Victor said impulsively. He regretted the words as soon as they were out of his mouth, but it was too late to take them back. Husband and wife looked over the seat at him, but Robbie stared meaningfully at the white paper bag under Victor’s arm.

“It’s just some old rolls and stuff,” Victor said. He shoved the bag at the boy, feeling resentful, and somehow outmaneuvered, although he didn’t exactly understand how, or by whom. “Here. Take it.”

Robbie snatched the bag from his hand and tore it open. “There’s all kinds of rolls and things, Ma,” he said. He started to take one, and looked at his mother. “It’s okay, ain’t it? He said we could.”

“You sure?” she asked, looking directly at Victor. He wanted to change his mind, say, no, I think I will keep them for myself after all, but her voice and her look were so plaintive, that he nodded his head and said, ““It’s okay. Someone gave them to me, so I guess I’m just passing them on.”

The boy took a big cinnamon roll, and handed the sack to his mother, and she took some kind of scone, and passed the bag on to her husband. He wolfed down a Danish and the bag went round again.

“You don’t want none?” Don asked, crumbs stuck to his lips.

Victor swallowed. “No, I ate just a little bit ago, I’m stuffed, thank you. You folks go ahead.”

They did, eating in silence, chewing frantically. He wondered how long it had been since they ate. The bag was empty in a minute or so. He watched regretfully as Don crumpled it up and dropped it on the floor by his feet.

“Well, I reckon we won’t starve, at least,” Don said. “We are surely grateful to you for sharing.”

“Yes, we thank you mightily,” Ellie said, and fixed her eyes on her son. “Robbie?”

“Thank you,” he mumbled with no sign of sincerity, licking the last ghost of flavor off his fingers.

“This place you’re going, in Pennsylvania,” Victor said, “How much gas do you think it would take to get there?”

“Not too much. This old bus, she eats gas, but even so, I expect ten dollars worth would see us there,” Don said. He sighed, and looked at the frosted over windshield. “Might as well be ten thousand, though, I guess. There’s nobody out tonight. You’re the first person to come by in an hour or more.”

They sat in silence for a long time. Victor thought of the money in his pocket, and those motels across town. Even if he could get to them, there was no guarantee that anyone would rent him a room for the money he had, and once he got there, he would be that much further away from anywhere else. If he went the other direction, he could probably make it to the Seven Eleven. He could get hot coffee there, and a hot dog, and probably they would let him hang out for a while, maybe the rest of the night, if he caused no trouble.

He took the crumpled bills out of his pocket. “I’ve got,” he said, and paused to count them, as if he didn’t know exactly how many there were. “I’ve got eleven dollars here. I could let you have seven of them, if you think that will be enough.”

Don’s eyes widened hopefully. “I expect it might. Anyway, if we got within a couple of miles, we might be able to hoof it the rest of the way, or maybe I could get there and bring somebody back for them. Her mother’s got an old pickup, or she might even have a can of gas. For sure we could get close enough. Only....” He took his eyes off the money and looked at Victor. “Only, it don’t seem right, taking your money. I mean, we already ate your food, and seeing as that’s all you got.”

“Oh, that doesn’t matter, I’ve got someplace I was headed, I just have to get there. Here.” He handed Don seven dollars, and then added another one to them. That left him three. That would get him a coffee and a hot dog, or a donut, anyway.

“Well, if you’re sure?” Don gave his wife a look. She licked her lips and held her breath. “I’ve got a gas can in the back, I’ll walk to that Sheetz station we passed a bit ago, and get enough gas to drive us there. You want to wait here, in the car? Say, you could come to Pennsylvania with us, if you like.”

“No, I got some place I got to go,” Victor said. He flung open the car door and got out quick, before the wind could come in after him. Before, he thought grimly, they could wish him a Merry Christmas, but he was too late. Don said it, and then Ellie, and even little Robbie.

“Same to you,” he said back, closing the door, and started off. He cursed himself for a fool all over again. Here he was now, in nothing but a light windbreaker, his food all gone, and nothing but three dollars in his pocket. Talk about your Merry Christmases.

* * * *

He wasn’t sure how far he had walked, or how long—he was light headed now, and he could scarcely feel his feet, lifting and coming down in the snow—when the little girl walked up to him, seeming to come out of nowhere. She was dressed in white, and her face was so pale, she could almost have been conjured up by the snow.

“Mister,” she said without preamble. “I am so cold and hungry, and I got no place to go.”

“Oh, hell’s bells,” he said aloud. He ought to have known, he thought angrily, the way this damned night was going. He yanked the last three dollars out of his pocket and thrust it toward her, but to his surprise, she took a step back from him and did not take it.

“It won’t work if you resent giving it,” she said. “You have to let it go.”

“Won’t work? Won’t work for what?” There was a buzzing in his head, like a host of wasps was in there. He handed the money to her again, but she only shook her head.

He dropped to his knees in the snow and took hold of her shoulders. She felt thin as a bird.

“You are one strange little girl,” he said. “I been giving and giving all night, and you’re the first one refused to take.”

“You have to share it. Not what we give, but what we share, for the gift without the giver is bare.”

He smiled into her face despite everything. There was something about her, a luminescence. She almost seemed to glow in the dark and the falling snow.

“I don’t understand what you are saying,” he said. He had a vague idea there was something else, earlier this evening, that he hadn’t understood either, but he was too tired and cold to think straight.

“If you bless it, we will both share in the blessing.”

“Well, then, if that’s the way of it,” he said wearily. “Take it then, and I surely do bless it, and I bless you.”

She did take the money then from his frozen fingers. Hers felt oddly warm when he touched them. She closed her eyes and looked down, and seemed to be praying. He closed his too, and tried what she said, tried to let the money go, to bless it.

He thought, out of the blue, of his mother again, of an incident when he had been just a boy, he couldn’t have been more than eight or nine. His mother had loaded up a basket of food from their cellar, to take to an aunt who was doing poorly. Mostly, in the winter, they lived on what she had put up in the cellar, and seeing the jars disappear from the shelves, he had said, “Won’t we need this food before the winter is out?”

She had given him a stern look, and said, “I never have been and never will be too poor to share what I have, because that is the worst kind of poverty: that is the poverty of the spirit.”

Yes, she was right, and the little girl, too. He had given what he had, but he hadn’t let go of it, he hadn’t shared it. He had resented everything that he had given, and his resentment had held on to everything even when it was gone from his possession. He thought back on his coat, and made an effort to bless the warmth that it might give the old man, and he thought of the family huddled in their car, and blessed the food he had given them, and the money; and the little girl...he opened his eyes, but she was gone.

Probably she was somewhere looking for shelter, or more likely, something to eat. He hoped she found it, before the night got any worse. The snow seemed to be coming down harder now, although, oddly, he didn’t feel anywhere near as cold as he had before. He felt hot, if anything. He undid a couple of buttons, and stumbled to his feet. He was light headed, though. He couldn’t exactly think where he was, or where he was headed. No place, really, he supposed. He had no place to go, did he, and nothing to do when he got there?

He began to stagger through the snow, singing softly to himself. “What child is this...?”

“Mister?”

He looked, and there was the girl again, right beside him. “Why, I thought you had gone,” he said. “Why’d you want to hang around, anyway? You ought to be looking for something to eat. The Seven Eleven is open, I bet, if I knew which way that was.”

“Come with me,” she said, and took hold of his hand.

He held back, but she tugged at him. “Hurry,” she said. “This way.”

“Well, that’s just a back alley,” he said, “There isn’t going to be anything down that way.”

But there was. They came round the corner, and the night fled before the light that spilled out of the windows ahead of them, and the lamp shining over the door, and the sign that said, Antoinette’s.

He stopped in his tracks, gaping in astonishment, and while he stared, the door of the restaurant opened, and there was Antoinette herself framed in it, she looked a lot like Karen Delvecchio. She saw him and smiled, and waved.

“Hurry, come on in,” she called to him.

“Little girl,” he started to say, but she had disappeared again, and when he looked down, he saw only his own footprints in the snow.

Why, there she was, in the doorway with Antoinette, and as he stared, the others came out and crowded around them, too—the old man, still in the blue parka, and the family from the car, Don and Ellie, he could see now that she was pregnant, and Robbie, balanced on his crutch.

“Come on,” they called to him, and “Supper’s ready,” and “The fire is warm.”

“We’re all just waiting for you,” Ellie said, “Hurry, now.”

He did. He began to run, and then he was flying, and they waved and called, and Antoinette laughed gaily and said, “Welcome, come on in, welcome to Antoinette’s.”