Читать книгу Renaissance Art - Victoria Charles - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I. Art in Italy

The Italian Early Renaissance

ОглавлениеThe earliest traces of the Renaissance are found in Florence. In the fourteenth century, the town already had 120,000 inhabitants and was the leading power in middle Italy. The most famous artists of this time lived here – at least at times – Giotto (probably 1266 to 1336), Donatello (1386 to 1466), Masaccio (1401 to 1429), Michelangelo (1475 to 1564), Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378 to 1455).

Brunelleschi secured a tender in 1420 to reconstruct the Florentine Cathedral, which was to receive a dome as a proud landmark. The foundation of his design was the dome of the Pantheon, originating in the Roman Empire. He deviated from the model by designing an elliptical dome resting on an octagonal foundation (the tambour). In his other buildings, he followed the forms of columns, beams and chapters of the Greek-Roman master builders. However, owing to the lack of new ideas, only the crowning dome motif was adopted in the central construction, in the form of the Greek cross or in the basilica in the form of the Latin cross. Instead, the embellishments taken from the Roman ruins were further developed according to classical patterns. The master builders of the Renaissance fully understood the richness and delicateness, as well as the power of size in Roman buildings, and complemented it with a light splendour. Brunelleschi, in particular, demonstrated this in the chapel erected in the monastery yard of Santa Croce for the Pazzi Family, with its portico born by Corinthian columns, in the inside of the Medici Church San Lorenzo and the sacristy belonging to it. These buildings have never been surpassed by any later, similar building in so far as the harmony of their individual parts is in proportion to the entire building.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404 to 1472), who like Brunelleschi was not only a master builder, but at the same time also a significant art historian with his writings About Painting (1435) and About Architecture (1451), was probably the first to articulate this quest for harmony. He compared architecture to music. For him, harmony was the ideal of beauty, because for him beauty meant “…nothing other than the harmony of the individual limbs and parts, so that nothing can be added or taken away without damaging it”. This principle of the science of beauty has remained unchanged since then.

Alberti developed a second type of Florentine palace for the Palazzo Rucellai, for which the facade was structured by flat pilasters arranged between the windows throughout all storeys.

Andrea della Robbia, The Madonna of the Stonemasons, 1475–1480.

Glazed terracotta, 134 × 96 cm.

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Donatello, Virgin and Child, 1440.

Terracotta, h: 158.2 cm.

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

In Rome, however, there was an architect of the same standard as the Florentine master builders: Luciano da Laurana (1420/1425 to 1479), who had been working in Urbano until then, erecting parts of the ducal palace there. He imparted his feeling for monumental design, for relations as well as planning and execution of even the smallest details to his most important pupil, the painter and master builder Donato Bramante (1444 to 1514), who became the founder of Italian architecture High Renaissance. Bramante had been in Milan since 1472, where he had not only built the first post-Roman coffer dome onto the church of Santa Maria presso S. Satiro and had also erected the church Santa Maria delle Grazie and several palaces, but had also worked there as a master builder of fortresses before moving to Pavia and in 1499 to Rome. As was common in the Lombardy at that time, he built the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie as a brick building, focusing on the sub-structure. Using ornamentation covering to cover all parts of buildings had been a feature of the Lombards’ style since the early Middle Ages.

This type of design, with incrustations succeeding medieval mosaics, was very quickly adopted by the Venetians, who had always attached much greater value to an artistic element rather than an architectonic structural feature. Excellent examples of these facade designs are the churches of San Zaccaria and Santa Maria di Miracoli, looking like true gems and demonstrating the love of glory and splendour of the rich Venetian merchants. The Venetian master builder Pietro Lombardo (about 1435 to 1515) showed that a strong architectonic feeling was also very much present here with one of the most beautiful palaces in Venice at that time, the three-storey Palazzo Vendramin-Calergi.

The architect Brunelleschi had succeeded in implementing a new and modern method of construction. But gradually a sensitivity toward nature, defined as one of the foundations in Renaissance, becomes transparent in some sculptural work of the young goldsmith Ghiberti, which can be found almost at the same time in the Dutch painter brothers Jan (around 1390 to 1441) and Hubert (around 1370 to 1426) Van Eyck, who began the Ghent Altar. During this twenty year period, Ghiberti worked on the bronze northern door of the baptistery and the sense of beauty of the Italians continued to develop. Giotto had further developed the laws of central perspective, discovered by mathematicians, for painting – later Alberti and Brunelleschi continued his work. Florentine painters eagerly took up the results, subsequently engaging sculptors with their enthusiasm. Ghiberti perfected the artistic elements in the relief sculpture. With this, he counterbalanced the certainly more versatile Donatello, who, after all, had dominated Italian sculpture for a whole century.

After a project of Donato Bramante, Santa Maria della Consolazione, 1508.

Todi.

School of Piero della Francesca (Laurana or Giuliano da Sangallo?), Ideal City, c. 1460.

Oil on wood panel, 60 × 200 cm.

Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino.

Donatello had succeeded in doing what Brunelleschi was trying to do: to realise the expression of liveliness in every material, in wood, clay and stone, independent of reality. The figures’ terrible experiences of poverty, pain and misery are reflected in his reproduction of them. In his portrayals of women and men, he was able to express everything that constituted their personalities. Additionally, none of his contemporaries were superior to him in their decorations of pulpits, altars and tombs, and these include his stone relief of Annunciation of the Virgin in Santa Croce or the marble reliefs of the dancing children on the organ ledge in the Florentine Cathedral. His St George, created in 1416 for Or San Michele, was the first still figure in a classical sense and was followed by a bronze statue of David, the first free standing plastic nude portrayal around 1430, and in 1432 the first worldly bust, with Bust of Niccolo da Uzzano. Finally, in 1447, he completed the first equestrian monument of Renaissance plastic with the bronze Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata, the Venetian mercenary leader, (around 1370 to 1443), which he created for Padua.

Donatello’s rank and fame was only achieved by one other person, the sculptor Luca della Robbia (1400 to 1482), who not only created the singer’s pulpit in Florence Cathedral (1431/1438), but also the bronze reliefs (1464/1469) at the northern sacristy of the Cathedral. His most important achievement, however, is his painted and glazed clay work. The works, which were initially made as round or half-round reliefs, were intended as ornamentation for architectonic rooms. But they found a role elsewhere – the Madonna with Child accompanied by Two Angels, surrounded by flower festoons and fruit wreaths in the lunette of Via d’Angelo is a rather splendid result of his creations. As Donatello’s skills culminated in his portraits of men, Robbia’s mastery is demonstrated in his graceful portrays of childlike and feminine figures – there was nothing more beautiful in Italian sculpture in the fifteenth century.

The demands on the design of these products rose to the extent with which the skills in manufacturing glazed clay work in Italy increased. In the end, not only altars and individual figures but also entire groups of figures were made using this technique, which left the artist complete freedom with regard to the design. Luca della Robbia passed his skills and his experience on to his nephew Andrea della Robbia (1435 to 1525). He in turn, and his sons Giovanni (1469 until after 1529) and Girolamo (1488 to 1566) developed the technique of glazed terracotta even further and together with them created the famous round reliefs of the Foundling Children on the frieze above the hall of the Florence orphanage during the years from 1463 to 1466.

Pisanello (Antonio Puccio), Portrait of a Princess, c. 1435–1440.

Oil on wood panel, 43 × 30 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

The fact that the production of the workshop of the della Robbia Family can still be admired nowadays in many places on Northern Italy demonstrates that the terracotta was not only to the taste of the general Italian public but also to that of the Europeans generally, and that the style was gaining more and more lovers. At the same time we should not forget that no other century was as favourably inclined towards sculptural design as the fifteenth century. Thus Donatello’s seeds bore splendid fruit. His two most important students, the sculptor Desiderio da Settignano (approximately 1428 to 1464) and the painter, sculptor, goldsmith and bronze caster Andrea del Verrocchio (1435/1436–1488), continued to run his school in his way of thinking. Especially the latter not only created a number of altarpieces, but also became the most important sculptor in Florence. He cast the statue of David, for instance, (around 1475) and the Equestrian Statue (1479) of the mercenary leader Bartolomeo Colleoni (1400 to 1475) in Venice. Verrocchio’s style prepared the transition to the High Renaissance.

Settignano has left considerably fewer pieces of art than Verrocchio and mainly occupied himself with marble Madonna reliefs, figures of children and busts of young girls. He passed his skills and knowledge on to his most important student, Antonio Rosselino (1427 to 1479), whose main piece of work is the tomb of the Cardinal of Portugal in San Miniato al Monte in Florence.

Among Rosselino’s students was Mino da Fiesole (1431 to 1484), who, while originally a stonemason, became the best marble technician of his time and created gravestones in the form of monumental wall graves, and Benedetto da Maiano. Fiesole’s art mainly lived on imitating nature, and was thus too limited to lend variety to his large production.

Domenico Veneziano, Portrait of a Young Woman, c. 1465.

Oil on wood panel, 51 × 35 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Dresden.

The second half of the fifteenth century shows the gradual transition from popular marble processing to the more austere bronze casting, and the two David statues are examples of this. Donatello’s work shows a rather thoughtful David, the other, by Verrocchio, in complete contrast, created in the ideal form of naturalism, a self-confident youth, who is smiling, satisfied with his successful battle, Goliath’s head chopped off at his feet. This smile, which has frequently, but to no avail, been copied by stonemasons has become a trade mark of Verocchio’s school. Only one artist really succeeded in conjuring this smile onto some of his own work: Leonardo da Vinci, also a student of Verrocchio. The sculptor Verrocchio has to share his fame with the painter Verrocchio, who has only left few paintings behind. Among them are The Madonna (1470/1475), Tobias and the Angel, also (1470/75), as well as the Baptism of Christ, painted in tempera colours (1474). As the painter, master builder and art writer Giorgio Vasari (1511 to 1574) recorded convincingly, Leonardo da Vinci painted the angel kneeling in the foreground in this picture. Later, he possibly painted over this picture in oil after Verrocchio had moved away to Venice.

Apart from the statue of the young David, another sculpture belonging to his masterpieces is surely Christ and St Thomas in a niche in the Church of Or San Michele and the Equestrian Statue of Colleoni, which he did not live to see completed.

In Rome, the painter and goldsmith Antonio del Pollaiuolo (around 1430 to 1498) operated in a workshop, creating the first small sculptures there. His pen-and-ink-drawing, possibly a draft for a relief, Fighting Naked Men (approximately 1470/1475) and the copperplate engraving Battle of the Ten Naked Men (around 1470) were to break new ground in nude art. His most important works of art however, are the bronze tombs of the popes Sixtus V (1521 to 1590) and Innocent VIII (1432 to 1492) in St Peter’s.

The development in the field of painting in Florence took place at about the same time as that in the field of sculpture, and raised it to a rich and splendid standard. Initially, the representatives of these two directions were irreconcilably opposed to each other, each stubbornly insisting on their own points of view. Finally, approximately in the middle of the fifteenth century, a certain fusion took place, the monumental always remaining a basic theme in Florentine art, which now found its expression in the monumental fresco-painting led by Masaccio and the Dominican monk Fra Giovanni da Fiesole, called Fra Angelico (1387 to 1455).

Fra Angelico (Fra Giovanni da Fiesole), The Deposition of the Cross (Pala di Santa Trinità), 1437–1440.

Tempera on wood panel, 176 × 185 cm.

Museo di San Marco, Florence.

Fra Angelico, who first worked in Florence and later in Rome, combined Gothic influences with naturalism in his work, which was exclusively religious, distinguishing itself with its blissful depth of feeling. His artistic roots lay in his devout disposition, which was reflected in his numerous figures of the Virgin Mary and angels. His skilful work with colours is shown to their best advantage both in his numerous frescoes, which have mostly been well preserved, as well as in his panel paintings. The most important frescoes (around 1436/1446) can be found in the chapter house, the cloister and some cells in the former Dominican monastery San Marco. The Coronation of the Virgin is seen by many experts as outstanding amongst all other frescoes. Fra Angelico took up this subject several times.

One of Fra Angelico’s most well-known successors is the Florentine Fra Filippo Lippi (around 1406 to 1469), who lived as a Carmelite monk for approximately five decades and was ordained priest in Padua in 1434, but later left the order. He took on Masaccio’s school of thought and sense of beauty with his softly modelled line-work and splendid colours. He gave the female element a significant role – not only in his life but also in his frescoes and his numerous panel paintings. In his figures of angels, he uses girls from his surroundings as models and shows a sense and understanding for the fashion of that time. In his frescoes he achieved monumental greatness and left his most beautiful creations in his panel paintings. Similar to Fra Angelico, the Coronation of the Virgin (1441/1447) was also an important subject for him. Contrary to Fra Angelico however, he pushed the actual coronation somewhat to the background, and clearly put a lot more emphasis on the figures of the clergymen kneeling in the foreground as well as the women and children he portrayed. This tendency towards portraying and therefore honouring the individual is mainly demonstrated in his Madonna pictures, expressing significant religious feelings. This becomes increasingly apparent in his painting Madonna with Two Angels (mid-fifteenth century). In comparison, he created a lively background to the Madonna, who sits at the front with the portrayal of the confinement of St Anna on the round picture Madonna and Child (around 1452). This childbed served later artists as a welcome model.

Fra Filippo Lippi’s most important student was without doubt Sandro Botticelli (around 1445 to 1510). But the headstrong Sandro, his Adoration of the Magi contains a self-portrait on the right side, insisted on becoming a painter, thus finally ending up at Fra Filippo Lippi’s as an apprentice. Later on, he was close to the circle of humanists around the chief councillor Lorenzo de Medici (The Magnificent; 1449 to 1492). Botticelli was one of the first to become deeply involved in the subjects of antique mythology, for instance in the most famous of his paintings, the Birth of Venus (around 1482/1483), and he liked to include antique buildings in the background of his work. Above all, he created allegorical and religious work, and during his activities in Rome between 1481 and 1483 also frescoes in the Sistine Chapel in cooperation with others. Another of his pictures is Spring (1485/1487), in which the merry and festive life in Florence is reflected.

Fra Filippo Lippi, Madonna with the Child and Two Angels, 1465.

Tempera on wood, 95 × 62 cm.

Galleria degi Uffizi, Florence.

In many of his pieces of work there is a lavish abundance of flowers and fruit, into which he places his slender girls and women with their fluttering, flowing gowns, as well as the Madonna’s, surrounded by serious saints. In some Madonna portrayals we can feel the influence of the repentance-preacher and Dominican monk Girolamo Savonarola (1452 to 1498), of whom Botticelli remained an ardent follower, even after his violent death. He also repeatedly painted the Adoration of the Magi, once also commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici, and in this painting we do not only see the members of this family but also their immediate circle of friends and his followers. His individual portraits such as Portrait of a Young Man in a Red Cap (around 1474), Giuliano de’ Medici (around 1478) and Portrait of a Young Woman (around 1480/1485) prove that he was also a brilliant portraitist. From his time in Rome he also left one of his most mysterious paintings: The Outcast (1495), with the crying or desperate figure of a woman on the steps in front of the fortress-like wall with the closed gate. Botticelli, who had been wrongly forgotten for a long time, is now regarded as one of the greatest masters of the Renaissance.

Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi), Madonna of the Book, c. 1483.

Tempera on wood panel, 58 × 39.5 cm.

Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan.

His most significant student was doubtlessly Filippino Lippi (around 1457 to 1504), the son of Fra Filippo Lippi. Initially strongly influenced by Botticelli, he later freed himself from him and created several significant pieces of work in his own right. Among these are an Adoration of the Magi, commissioned by the Medici, and following its interruption due to Masaccio’s death, the completion of the painting of the Brancacci Chapel showing a fresco cycle with Scenes from the Life of St Peter (1481/1482), a Coronation of the Virgin and a Madonna.

In spite of these indisputable performances, his reputation and awareness level do not measure up to those of his contemporary Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449 to 1494). Like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio also first completed an apprenticeship as a goldsmith, and was already unquestionably successful when he dedicated himself entirely to painting. In 1480 and 1481 he created monumental and beautifully designed frescoes in the Sistine Chapel and in 1482/83 to 1485 in the Florentine Santa Trinità, among which The Last Supper in the Church of Ognissanti stands out in particular, and can be considered a forerunner to Leonardo’s. Ghirlandaio included life around him into his work and did not hesitate at all to arrange biblical stories as scenes of contemporary Florentine good living, in order to give the viewer a better understanding of its deeper meaning. This is especially apparent in the frescoes he painted in the choir of Santa Maria Novella (1490).

Among the absolute masters of Italian painting outside of Florence is Piero della Francesca (1416 to 1492), who should be regarded as one of the most brilliant painters of the Early Renaissance and was particularly outstanding due to his excellent knowledge of anatomy and perspective. Piero della Francesca created a style that combines monumental size with the transparent beauty of colour and light, and therefore influenced the entire northern and middle Italian painting of the Quattrocento. His main work is the cycle of frescoes from the Legend of the True Cross in the choir of San Francesco in Arezzo (1451/1466) and a Baptism of Christ (1448/1450).

One of Piero della Francesca’s most important students was Luca Signorelli (1440/1450 to 1523). His harshly modelled nudes, in movement and the adoption of ancient subjects, made him one of Michelangelo’s role models. What kind of mastery he had already achieved in the portrayal of the human body as a young man is depicted in a mythological picture, rich in figures and probably commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici. Michelangelo paid Signorelli his respects, when he adopted the woman riding on the Devil’s back in one of his pieces of work, without any changes. But we can also still find Signorelli’s frescoes and altarpieces in other large and small villages and towns in southern Tuscany and in Umbria. From their relatively good condition in relation to the colours, we may conclude that he made use of the new technique with oil-paint that originated in the Netherlands. Signorelli also worked in Rome for some years, where in 1481/1482 he painted the fresco with The Testament and Death of Moses in the Sistine Chapel. In Venice, Jacopo Bellini, the father of the famous Gentile Bellini became his student. Among Jacopo’s main work is the altar with the Adoration of the Magi (1423) as well as frescoes, of which only one Madonna (1425) has been preserved in the Orvieto Cathedral.

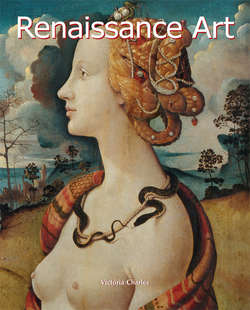

Piero di Cosimo, Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci, c. 1485.

Oil on panel, 57 × 42 cm.

Musée Condé, Chantilly.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, An Old Man with his Grandson, 1488.

Tempera on panel, 62 × 46 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Another Umbrian painter was Lehrzeit Perugino (around 1448 to 1524). Although he was one of the most important masters of Umbrian style and thus held in high esteem by his contemporaries, he achieved greater significance as a teacher of Raphael, whose first stage of development he had a crucial influence on, than as an artist in his own right. Perugino later also had close contact with the Florentine circle around Verrocchio. However he, only initially and very hesitantly, adopted the view of naturalism prevailing there, and preferred to remain true to his softer, successful style. This was because his contemporaries always demanded sensitive devotional pictures, which nobody except he knew how to paint with such a beautiful lustre of colours. In his paintings St Sebastian and Madonna and Child enthroned with St John the Baptist this becomes quite clear. The disadvantage of the popularity of his paintings was, of course, that it led to a mass production, during which even the expression of the greatest heavenly rapture became a cliché. But the series of frescoes he painted in the Sistine Chapel from 1480 with, among others, Christ gives Peter the Key to the Kingdom of Heaven or the altar with Adoration of the Child (1491), or the Vision of St Bernhard (around 1493), which was probably painted for the Cistercian church del Castello in Florence, belong to the absolute masterpieces of religious paintings. But he also became familiar with ancient art.

However, in these classical portrayals his student Bernadino Pinturicchio (1455 to 1513) was far superior to him. In 1481 to 1483 he worked together with Perugino in the Sistine Chapel on frescoes with subjects from the Old and New Testament, but he also created his own frescoes, whose meticulous execution was reminiscent of miniature painting, in the Vatican Hall of Saints. This earned him the approval and goodwill of his clients, as well as did his well-developed sense for fitting out a large room in a unified, decorative style. This talent made him the founder of Renaissance decoration.

Apart from the Umbrian school, there were also schools in Padua, Bologna and Venice, which were of significance in the second half of the fifteenth century.

From the artists of these schools, Andrea Mantegna (1431 to 1506) is doubtlessly to be regarded as one of the greatest. Mantegna’s greatness lies in the depiction of important characters that he mainly found in classical works of art. This enthusiasm for classical art, which he wanted to match, dominated Mantegna’s life. He had been working in Mantua for the margrave Ludovico Gonzaga since 1460 and provided the spouses’ room with wall and ceiling decorations in their Castello di Corte in 1473 and 1474.

Perugino (Pietro di Cristoforo Vannucci), St Sebastian, c. 1490–1500.

Oil on wood, 176 × 116 cm.

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

In this work he proved his skills in perspective foreshortening in vault frescoes, and by far surpassed his professional colleagues in Florence regarding power and greatness of the characteristics. For a series of paintings destined for a room in the margrave’s palace, he also proved his change of direction to the classics. More than once Mantegna demonstrates a certain sympathy for the “underdogs”. One of the examples for this attitude is his dignified portrayal of the lower classes in religious pictures and the illustration of the prisoners in Triumph of Caesar (1488/1492). His art always remained directed towards the great and serious, and he only seldom moderated his harsh forms through pleasing gracefulness. Examples for this are among others the Madonna della Vittoria and John the Baptist (1496) in which the kneeling Duke Francesco Gonzaga is being blessed, as well as the tempera painting the Parnassus (1497) with Mars and Venus on a fanciful rock throne with the muses dancing in front and Apollo’s string playing. Mantegna’s revival of classical antiquity was so convincing that it even cast its spell over Raphael.

Whilst Gentile Bellini is more of an art historian, Giovanni continued the artistic lines of his father and brother-in-law Mantegna. Giovanni Bellini’s favourite subject was without doubt the Madonna, portrayed alone, with child or sitting enthroned as a Madonna surrounded by saints. In these figures, as well as old and young or male and female figures he created types of beauty, which have not been surpassed in their rapturous emotional state of mind. In the composition of the colouring there is always a harmony reminiscent of music, and this element of life, indispensable to Venetians, is not missing on any of the Bellini altarpieces. In contrast, many devotional pictures of the Florentines and Paduans originating from this time seem austere and stern, and those of the Umbrian painters detached and tearful. They were all much less likely to evoke devotion than the paintings of the Venetians.

In the colourful art of the Early Renaissance, represented by Bellini, we can already feel the transition to the High Renaissance approaching that was then actually made by his students, and in his mythological paintings he had already thrown open the door to the High Renaissance.