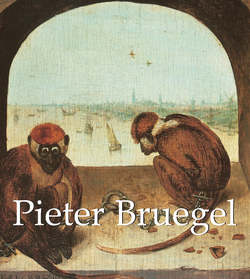

Читать книгу Pieter Bruegel - Victoria Charles - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Century of Pieter Bruegel the Elder

ОглавлениеBruegel’s work constitutes a definitive illustration for the most scholarly of historical treatises of this period. He succeeded in capturing the souls of his models in his figure of a dancing peasant or at a delicious feast with a few figures seated around a table. Even in their paintings of gentle fire-lit interiors, the old masters always included a window that opened onto the landscape that showed details of contemporary daily life.

Pride from the series Seven Deadly Sins

1557

Pen and brown ink, 22.9 × 30 cm

Institut néerlandais, Fondation Custodia, F. Lugt Collection, Paris

Pieter Bruegel brought these tiny realist compositions to the foreground, designing them to bring the viewer’s sentiment closer to the already poignant scenes of Christ’s Passion. This became the subject upon which Bruegel, with his jolly and satirical Flemish verve, exerted his keen sense of observation, and his marvellous gift for capturing the burlesque or tragic nature of the masses.

Elck or Everyman

1558

Pen and brown ink, 21 × 29.3 cm

British Museum, London

When considered from another point of view, it is tempting to define Bruegel, as Van Mander does, as a painter of the peasantry, for it is true that he produced a great number of pastoral scenes. In particular, Bruegel studied the morals of rural life and seems to have been attracted to his subjects through a secret sympathy and certain affinity for their thinking and sentiments which were born out of his own common origins.

The Alchemist

1558

Pen and brown ink, 30.8 × 45.3 cm

Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin

This connection withstood his stays in large cities, his contact with elite circles of scholars and artists, and his encounters with Italian landscapes and masterpieces. None of this would come to change Bruegel’s powerful originality, as it resisted influence like a diamond resists the marks of other stones.

The Last Judgement

1558

Pen and brown ink, 23 × 30 cm

Graphische Sammlung, Albertina, Vienna

Although Bruegel found lasting pleasure in the portrayal of the lives of the peasantry, it is not a sufficient reason to reduce this illustrator of life to the specialised label of genre painter. His characters, be they rustic or bourgeois, must be seen in the light of the appetites, ulterior motives, material needs, and moral aspirations that were reflections of their time.

Twelve Flemish Proverbs

1558

Tempera on oak, 74.5 × 98.4 cm

Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

With a sudden glow, each face, by the hundreds in certain canvasses, illuminates anecdotes from Van Vaernewyck’s memoirs: blinking eyes in a face creased with malice, others with angular, hastily composed features possessing a carved marionette’s strange wooden steadiness, or a particular flat-browed profile with a lipless gash of a mouth. The group compositions reveal the depth of Bruegel’s genius even more than their individual faces.

Skaters before the Gate of Saint George

1558-1559

Pen and brown ink, 21.3 × 29.8 cm

Private collection, United States

The Massacre of the Innocents represents all of the arrogance, insolence, and the unbearable burden of foreign domination at the hands of these mercenaries, clustered together like a block of steel, contemptuous and invulnerable, pushing before the chests of their horses, the hounded flock of unfortunates. These mothers, these peasants clasping their hands, these women collapsed in suffering, are those that Bruegel saw begging for their husbands, themselves, or even for their children to be spared.

Charity, from the series Seven Virtues

1559

Pen and brown ink, 22.4 × 29.9 cm

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

These are the unfortunate women he found weeping alongside the road, under the same December sky and in the same atmosphere of inexpressible sadness that envelops The Massacre of the Innocents. Yet the whole of Bruegel’s work is far more vast, boldly executed, and teeming with movement than these examples.

Netherlandish Proverbs

1559

Oil on wood panel, 117 × 163.5 cm

Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

What was Bruegel’s position in relation to the other painters of his time? In 1525, a few years before the probable date of Bruegel’s birth, Jan Gossaert, known as Mabuse or Maubeuge, returned from his stay in Italy. He was the first Flemish painter to admire the masterpieces accumulated for over two centuries in the churches and palaces of Rome and Florence.

Netherlandish Proverbs (detail)

1559

Oil on wood panel, 117 × 163.5 cm

Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

This was the era of Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci, who represented the most blinding brilliance of the blazing light of the Italian Renaissance. Yet, less than fifty years before, the Italians had borrowed aspects of the Flemish method of painting from nature, and the taut and powerful technique used by Jan de Bruges (as they called the elder Van Eyck), Hugues van der Goes, and Rogier van der Weyden.

Netherlandish Proverbs (detail)

1559

Oil on wood panel, 117 × 163.5 cm

Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

These borrowed techniques enabled the blossoming of Florentine art under Masolino da Panicale, Masaccio, and Andrea del Verrocchio, who were the direct precursors of the great Italian masters of the first half of the 16th century.

Bruegel’s art is not the result of any particular school in the strict sense of the word. The best of his students, his son Pieter, known as the ‘Hell Brueghel’, simply copied him.

The Fair at Hoboken

1559

Pen and brown ink, 26.5 × 39.4 cm

Courtauld Institute of Art, Lee Collection, London

Pieter Bruegel the Elder occupies an exceptional place in the history of Flemish painting, as much for the creative power of his genius as for his personal technique. It would be fair to consider him an extreme, a crowning achievement of the realist tendency that characterises Netherlandish painting.

The Fight between Carnival and Lent

1559

Oil on oak panel, 118 × 164.5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

He applies himself to his subjects which are drawn from the daily lives of the Flemish people with a primary concern for sincerity before satire. It was only after completing a scene of daily life that he would attach a proverb or a certain moral sense to it. His work is so natural that he frequently does not seem to have set out with the preconceived idea of painting a particular moral lesson or proverb.

The Fight between Carnival and Lent (detail)

1559

Oil on oak panel, 118 × 164.5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna