Читать книгу Gaudí - Victoria Charles - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Biography

ОглавлениеCasa Vicens, View of façade from Calle de Carolines

1852: Gaudí is born on 25 July, in the town of Reus.

1863: Gaudí starts his school education at the Convent of St Francis, Reus.

1868: Gaudí moves to Barcelona to complete his final year of secondary education at the Instituto Jaume Baulmes.

1869: Gaudí enrols in the Faculty of Science at the University of Barcelona.

1873: Gaudí enrols in the School of Architecture.

1875: Gaudí is called up for military service.

1876: The death of his elder brother Francesc and his mother Antonia.

1878: Gaudí qualifies as an architect.

1879: Gaudí joins the excursionistas. His sister Rosa dies.

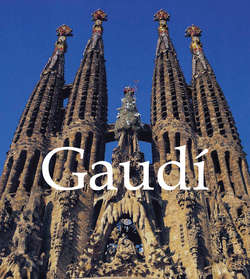

1883: Gaudí starts work on the Sagrada Familia, the following year he is officially named architect of the project. Begins work on Casa Vicens and designs El Capricho.

1884: Gaudí begins building Las Corts de Sarría, on Güell estate.

1886: Work begins on the Güell Palace.

1888: Universal exhibition in Barcelona, including exhibit designed by Gaudí. Gaudí begins constructing the Colegio Teresiano. He begins work on the Episcopal Palace in Astorga and the Casa Botines in León; projects which continue until 1891.

1891: Gaudí travels to Tangiers and prepares designs for a Franciscan Mission.

1894: Gaudí subjects himself to strict Lenten fast and is bedridden.

1895: Gaudí collaborates on the Bodegas Güell with Francesc Berenguer.

1898: Gaudí begins the Casa Calvet. He develops model for the Crypt at the Colonía Güell.

1899: Gaudí receives award for municipal council for Casa Calvet.

1900: Work begins on the Park Güell

1903: Restoration of Mallora Cathedral begins.

1905: Gaudí, his father and niece move to a house in the Park Güell.

1906: Gaudí’s father, Francesc, dies.

1910: Gaudí’s first exhibition abroad, at the Grand Palais in Paris.

1911: Gaudí contracts brucellosis.

1912: Gaudí’s niece, Rosa Egea i Gaudí, dies.

1925: The first of the Apostle Towers for the Sagrada Familia is completed.

1926: Gaudí is knocked down by a tram on the 7 June and dies three days later on 10 June.

The life of Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) is best told and analysed through a focused study of his works. The buildings, plans and designs testify to Gaudí’s character, interests and remarkable creativity in a way that research into his childhood, his daily routines and working habits can illuminate only dimly. In addition to this, Gaudí was not an academic thinker keen to preserve his thoughts and ideas for posterity through either teaching or writing. He worked in the sphere of practical, rather than theoretical work.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

General view

Were this not enough to challenge attempts to gauge the mind of this innovative architect the violence of Spain’s Civil War resulted in the destruction of a large part of the Gaudí archive, and this has denied a deeper understanding of Gaudí the man, his character and thoughts. On 29th July in the first year of the Spanish Civil war the Sagrada Familia was broken into, and documents, designs and architectural models stored in the crypt were destroyed. The absence of documentation limits the possibility of a searching biographical study, and it has encouraged rather more speculative interpretations of the architect. Today Gaudí has gained an almost mythic status in the same way that his buildings have become iconic.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

Entrance porch detail

While his work continues to attract the ‘devotions’ of many thousands of tourists, his life inspires a range of responses. Besides the academic scholarship of Joan Bassegoda i Nonnell, for example, or the recent biographical study of Gijs Van Hensenberg, the life of Gaudí has prompted hagiographies and more imaginative reflections. In a different vein Barcelona’s acclaimed opera house, el Liceu, premiered the opera Antoni Gaudí by Joan Guinjoan in 2004 and this process of cultural celebration has taken on a metaphysical dimension with the campaign by the Associació Pro Beataifició d’Antoni Gaudí to canonise him.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

View of entrance

The ongoing celebrations and constructions of Gaudí the man by various groups signals how in our ‘Post-Modern’ age the ascetic, inspired, untiring creator remains a key trope of creativity in the popular imagination. Gaudí remains an enigmatic figure and attempts to interpret him tend to tell us more about the interpreter, as is illustrated in the following quotations. Salvador Dalí records an exchange with the architect Le Corbusier in his essay As of the terrifying and edible beauty of modern-style architecture. Dalí stated, “…that the last great genius of architecture was called Gaudí whose name in Catalan means ‘enjoy’.”

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

Chimney

He comments that Le Corbusier’s face signalled his disagreement but Dalí continued, arguing that “the enjoyment and desire [which] are characteristic of Catholicism and of the Mediterranean Gothic” were “reinvented and brought to their paroxysm by Gaudí”. The notion of Gaudí and his architecture with which the Surrealist confronted the rational Modernist architect illustrates a recurring feature in the historiography of Gaudí, which is the concern to isolate Gaudí from the specific history of architecture and render him as a visionary genius.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

General view of façade

Furthermore, Dalí’s account aims to place Gaudí in a pre-history of Surrealism and identify Gaudí as a ‘prophet’ or precursor of the aesthetics and ideas of that avant-garde Modernist movement. While the devout Catholic and studious architect Gaudí may have considered anathema much of Dalí’s art and writing, he may not have disagreed entirely with Dalí’s comments cited here. However, it should be noted that to identify Gaudí as a proto-Surrealist risks obscuring Gaudí’s intellectual position, as well as his traditional religious beliefs. Considered from an historiographical angle Dalí’s statement suggests an insight into Gaudí’s continued appeal into the early twenty-first century.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

Detail of stained glass windows

It may be argued that the frequent reappropriation and ‘reinvention’ of past styles in contemporary art, fashion and design has helped shape the appeal for Gaudí’s artistic reappropriations, what Dalí termed his “paroxysm of the Gothic”. It is of the utmost relevance to note that Le Corbusier was by no means antipathetic to Gaudí. In 1927 he is recorded as saying, “What I had seen in Barcelona was the work of a man of extraordinary force, faith, and technical capacity… Gaudí is ‘the’ constructor of 1900, the professional builder in stone, iron, or bricks. His glory is acknowledged today in his own country. Gaudí was a great artist. Only they remain and will endure who touch the sensitive hearts of men…”

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

Coat of arms detail on façade

As will become apparent, Gaudí would have probably shared Le Corbusier’s sentiments more than Dalí’s. Le Corbusier’s criticism signals a different approach to the analysis of Gaudí’s work. It is examined in the specific context of architectural history. In the course of this book, analysis of Gaudí’s buildings seeks to balance the measured architectural analysis evoked by Le Corbusier with discussion of the shifting critical responses to Gaudí’s work such as Dalí’s. The foundation for this approach is a critical understanding of Gaudí’s life. His interests and the society of Barcelona, which shaped his work in important ways, need to be considered and they are the subjects to be treated here.

Episcopal Palace of Astorga

View from behind

It needs to be emphasised that in the absence of further information it is the buildings which are the best testament to the man. Although Gaudí was not born in Barcelona, the city which provided a key cultural dynamic to his architecture, he was born in Catalonia, in the small town of Reus. Biographers of Gaudí, often prompted by the architect himself, have identified in his provincial childhood experiences the origins of his later creativity. The belief that art may be an inherited gift underpins Gaudí’s assertion that his “quality of spatial apprehension” was inherited from the three generations of coppersmiths on his father’s side of the family, as well as a mariner on his mother’s side.

Tower of Bellesguard

View of the West side

Whatever truth there may be in Gaudí’s claim, we can be certain that his home life was comfortable and stable. The only shadow cast over his childhood was a period of severe illness. The psychological effects of this on the development of the young child’s imaginative faculties and spiritual convictions are hard to gauge, although his survival may be read as an early sign of a strong constitution and defiant determination. It can be asserted with more confidence that this period of Gaudí’s life introduced him to four factors that would be fundamental to his career: architecture, especially the Gothic; Catalan history and culture; Catholic doctrine and piety; and, finally, the forms and colours of the natural world. In many ways architecture acted as a medium to explore and reflect on the latter three. Besides the traces of Reus’s medieval heritage, the neighbouring towns and countryside provided a number of important buildings to visit, such as the famed pilgrimage Church of Montserrat and Tarragona’s impressive cathedral. Gaudí’s experiences of such places would have been coloured by an awareness of them as the cultural patrimony not of Spain, but the region of Catalonia, of which Barcelona is the capital.

Tower of Bellesguard

Ceramic mosaïc on the entrance bench

Tower of Bellesguard

Bench detail (the fish with four bars represent the former naval powers of Catalonia)

Catalonia had once been part of the independent Kingdom of Aragon, which first became linked to the Kingdom of Castile to form what we know as modern Spain in the fifteenth century. The process of balancing unification with regional autonomy is still being negotiated today and as a result Catalonia has developed a strong sense of national identity, with Barcelona at its centre. The fact that many of the buildings Gaudí visited were religious is a reminder of the particular role that religion played in the construction of Catalan identity, as it did in the histories of other regions of Spain.

Tower of Bellesguard

Bench detail (the fish with four bars represent the former naval powers of Catalonia)

As an adult, Gaudí would identify with both a defiant form of Catalan nationalism and a devout commitment to the Catholic Church. However, as a child and youth such serious concerns were a long way off.

Nonetheless, a keen youthful interest in architectural history and a concern for Catalan patrimony provided a foundation for his later ideological position. Besides visiting existing buildings Gaudí, accompanied by friends, would also seek out the ruins of once-great buildings and the traces of Catalonia’s history.

Tower of Bellesguard

Detail of entrance tiles (Lions and roosters, symbols of royal powers)

It would not seem fanciful to suggest that these excursions into the countryside inspired in Gaudí a creative vision of the landscape, stone, plants and other elements of the natural world. There is little verbal testimony of Gaudí’s youthful attitudes to nature, and we must wait to examine his architecture to gauge this aspect of his thinking. However, the clearest identification of the early signs of Gaudí’s creative and intellectual powers are exemplified by an important episode from his youth, his involvement in a project to restore the ruined Cistercian monastery of Poblet.

Tower of Bellesguard

Rooftop walkway

In 1867, accompanied by his childhood friends Eduardo Toda and José Ribera Sans, Gaudí visited the ruins of the twelfth-century monastery. Documentary evidence of their visits records their imaginative impressions: the Manuscrito de Poblet, written by Toda in 1870, lists their plans to restore the crumbling remains into an utopian cooperative, attracting the necessary labour force as well as a community of artists and writers, the combination of which would restore the monastery to a new life.

Tower of Bellesguard

Rib structures of the ceiling on the second floor

However, their youthful spirits were captured by the monastic ideal with art, life and pleasure as guiding principles, rather than by the restoration of Catholic tradition. It is worth noting that the Manuscrito de Poblet records the first known drawing by Gaudí of the heraldic shield of Poblet, which was produced in 1870. In the 1930s Toda would return and lead the restoration of this monastery, but by that time Gaudí had been dead for four years. The intervening years had been spent by Gaudí not simply in imaginative restorations of the ruins, but in a creative and innovative interpretation of the architectural language of the past, as well as its values.

Tower of Bellesguard

Rib structures of the ceiling on the second floor

It was as a student in Barcelona that this artistic process was initiated in earnest. Gaudí’s life in Barcelona began in the autumn of 1868. His elder brother, Francesc, was already there by then, studying medicine. During his first year he completed the final two compulsory courses of his secondary education at the Instituto de Jaume Baulmes. However, one may also assume that he spent considerable time discovering Barcelona’s architecture, both old and new. The following year Gaudí, aged 17, enrolled in the Science Faculty at the University of Barcelona.

Tower of Bellesguard

Detail of trilobite arches in parabolic form in the first attic

The five-year course that he attended covered various branches of mathematics as well as chemistry, physics and geography. His university results offer one means to measure Gaudí’s intellectual ability. He passed, although had to retake his final year before entering the School of Architecture in 1874. Testimony from fellow students record his commitment to study, yet also the difficulties he encountered especially in theoretical subjects such as geometry. The image of the student Gaudí that emerges from his biographers is a thinker who relished work in a practical context, but found theoretical and abstract principles both challenging and tedious.

Tower of Bellesguard

Lobby

Gaudí’s practical approach to solving complex architectonic problems, as opposed to drawing on mathematical solutions, is notable in his mature work, when he would employ models to develop his ideas. However, Gaudí’s mind was not only scientific. Prior to being accepted at the School of Architecture he had to prove himself at both architectural and life drawing. While no less was to be expected of an architecture student he also passed the school’s French language test. He clearly had some ability in languages as well as literature.

Tower of Bellesguard

South side

In the course of his life he mastered German and was an avid reader of Goethe’s poetry, much of which he knew by heart! Thus the profile offered by Gaudí’s academic record reveals a broad range of abilities. Perhaps more important is that these were accompanied by an avid enthusiasm for learning, in particular with regard to his chosen discipline. Study in the School of Architecture was structured firstly through academic courses in drawing skills for preparing architectural plans and designs and in gaining a knowledge of building materials.

Tower of Bellesguard

Building detail (gothic window)

In conjunction with these taught courses students also put their work into practice. Between 1874 and 1875 Gaudí’s projects included the design for a candelabrum, a water tower and, most notably, a cemetery gate. The following year his studies were interrupted by conscription to the army. Although Gaudí was decorated for his defence of the nation it seems he did not actually see action. The following year his projects were more taxing, having to design a patio for local government offices as well as a pavilion for the Spanish exhibit at one of the many grand international exhibitions that took place in Philadelphia.

Casa Calvet

General view

In the course of his student career he would also work on a shrine for the Virgin of Montserrat, designs for a hospital, a boating lake, a fountain and a holiday chalet. Having carried out this range of designs, Gaudí was trained to work from the small scale to the monumental, as well as being prepared to satisfy the different demands of potential clients, from institutional to ecclesiastical buildings and public to private spaces. As this range of work testifies, Gaudí’s student years were an extremely hard-working and productive period.

Theresan College

Brick work columns on the first floor

Of the few graphic and design works that have survived until today a number were part of his student projects. Although these works demonstrate his affiliation with the principles and ideas of his teachers, which are discussed in the following chapter, they mark the start of his career and highlight the dramatic changes he introduced into the practice of architecture. Despite the classical simplicity of the 1875 design for Gaudí’s cemetery-gate project, it is interesting to note the integration of sculptures and ironwork which would become central features of his later work.

Casa Calvet

Insect door knocker

Six angels line the sides of the archway, the two iron gates meet at a sculptural group of the Crucifixion with the Virgin and St. John the Baptist. Above, in the centre of the arch, is the figure of Christ as Judge of mankind and crowning the structure is the enthroned figure of God. Combined with other elements Gaudí created an iconographic programme based on the book of Revelation, the last book of the bible which recounts the mystical and eschatological visions of St. John the Evangelist.

Casa Calvet

Anagram detail

The addition of the flaming beacons on the four corners and what appears to be a censer, for incense, signals his interest in effects of light and organic forms of flame and smoke. Gaudí failed his assignment for this design as its descriptive setting was not considered the correct procedure for an architect!

Gaudí’s skills as a draughtsman are remarkable, and Gaudí’s teachers did recognise this even though they questioned some of his techniques. In his course of studies he was awarded an honour grade and was thus eligible to compete for a school prize.

Theresan College

General view

The project he entered for the competition was an elaborate lakeside pier, with steps to the water to board pleasure boats. It combines an elegant yet elaborate arcade of Gothic arches above which rise two cylindrical towers. The lakeside promenade is decorated with sculptures stood on pedestals, which are linked by a wrought-iron balustrade. Out of recognition of his teachers’ strictures on the principles of drawing, the references to reality are almost all but eliminated: faint touches of watercolour evoke the lake’s surface and a boat comes into dock. Closer study reveals the wealth of detail with which Gaudí imagined this building.

Theresan College

Corner view of building with the original coat of arms

Such attention to detail indicates the dedication of the young trainee architect, and the pressure of Gaudí’s workload during this period was added to by the need to support his studies by working for a number of architectural practices. Despite the challenges this must have posed, not to mention the emotional strain of the deaths of both his mother and elder brother, all of which he overcame through pure hard work, he finally qualified as an architect in 1878. However, there was a dispute between the lecturers over his qualification, which may signal that his excessive workload distracted him from his studies.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу