Читать книгу Between the Lines: My Autobiography - Victoria Pendleton - Страница 5

Laoshan Velodrome, Beijing,Tuesday 19 August 2008

ОглавлениеI’m going nowhere fast. On a set of whirling rollers, with my head down, it feels as if I’m flying without moving. The bike below me shudders a little from side to side but it never moves forward. It just spins on the gleaming drums, the wheels of an otherwise stationary machine whirring endlessly. My whole life shrinks down to these surreal moments. I try not to think about it now; but I can’t help it. I’m just one race away from becoming an Olympic champion.

A new song in my head starts prettily, lilting and yearning in headphones that are meant to shut out the madness and tension around me in the pits. As I get ready to return to the wooden track in another ten minutes, I look up and think of Scott. This song binds us together. I can sense him nearby, even if I can’t see him. He has to become invisible to me between my races, just as we have had to keep each other secret from the world these last few months. Maybe the furtive nature of our relationship should make me feel guilty; but it doesn’t. I allow myself the smallest of smiles, on the inside, behind my racing face.

On a steamy Tuesday evening in Beijing, a long way from home, the opening words to ‘Today’, by The Smashing Pumpkins, ring through me. They tell me that today is the greatest day I’ve ever known.

Today should become the greatest day of my life. In the final of the individual sprint I’m already a race up on Anna Meares, my old rival, the Australian rider who so often tries to bully and intimidate me. Meares is a formidable competitor but I’ll never forget how she once smashed her bike straight into mine to stop me winning. Scott, who is also an Australian, used to be part of the team that helped make Meares an Olympic champion four years ago in Athens. She won the 500m time trial while, at those same Games, I endured one of the most miserable experiences of my life. I cried like I’d never cried before.

Everything should be different now. Everything should be fantastic.

As I keep myself warm on the rollers the song begins to change in my head. I can now hear The Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan singing, with a muffled yelp, of burning his eyes out and tearing his heart out. I know the feeling. Racing, especially the tactical nightmare of an individual sprint, sometimes makes me want to scream. It can feel like torture.

Today, however, is different. Today I seem untouchable.

I can hardly feel my legs turning beneath me. I can see them pumping and pedalling, in a blur of bony knees and fastened feet, but it’s almost as if my legs have disappeared from the rest of my body. Usually, in competition, my legs are in a permanent state of fatigue. A nagging weariness runs through them, telling me how often they have gone up and down, round and round, in ceaseless circles. But during these long weeks in Beijing my legs have been unbelievably quiet. They lead down to my feet, touching the pedals, and I pump them effortlessly, hard and fast, up and down, round and round. There is no ache.

In the first race against Meares these legs of mine were unstoppable. I beat her without really extending myself, winning the first in a possible series of three sprints. If I win the next race I’ll have won Olympic gold – the only medal that I came all this way to take. It will be all over then, the waiting and the fretting, and I can go and find Scott. We can drink champagne and maybe even come out in the open. Then, and this rises up like an image of bliss on my static rollers, we can fly home happily.

I am going to win this race. I feel the certainty coursing through me. That arrogance goes against every neurotic bone in my body. Normally, I’m a seething tangle of doubt and insecurity. I question myself, and my ability, every pedal of the way. But not now, not today, not with The Smashing Pumpkins on a resounding loop; and not with my legs feeling so strong.

It’s taken my whole life to reach this point. The little girl trying desperately to stay in sight of her dad, pedalling up a hill until it seemed her heart might burst, would not believe we’d end up here. There were no Olympic dreams then. That small girl, me in a different world, just wanted Dad to slow down or look back to see that I was all right. But turning the pedals on the rollers, I can now imagine Dad driving me on, never glancing over his shoulder while I struggled to keep up with him. Dad would climb away from me on the long hills, a great amateur cyclist who would have loved to have had the chances I had, a father who didn’t often reassure me. I just wanted Dad to love me, and be proud of me, and so this is where I’ve ended up.

I’m riding this one for you, Dad, despite everything, because you, more than anyone, made me who I am – this racer going somewhere, chasing something that would make you very proud.

And this one is also for you, Mum, because you’re so different. You never wanted me to be anything but myself. You’ll love me just the same – whether I come home with a gold medal or, instead, I just give up and slip off this bike forever. I’ll be the same Lou to you. It might not make me a champion but I feel happy knowing I’m still Lou to Mum.

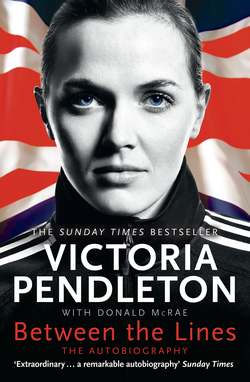

My name is Victoria Louise Pendleton. Alex, my twin brother, against whom I used to race so hard and so often when we were small, called me Lou-Lou for years. Our big sister, Nicola, was Nicky. And so, when Mum yelled up the stairs for one of us to get a move on, ‘Nicky’ and ‘Vicky’ sounded too similar. So Mum switched to Lou for me. Nicky, meanwhile, still sometimes calls me Scooby.

Scooby Lou might be starting to spin out but for the fact that I’ve been here before. There’s little time left and this is not a place for songs or families. This is race time. It’s the moment I’ve thought about so often. I’ve even dreaded it, especially these last few weeks as my need to win has intensified. We’re at the end of the Olympic track cycling programme in Beijing and I’ve sat and watched at a distance as one British gold medal after another has been won. I’ve not even been allowed at the velodrome; to keep my legs in their springy shape, I’ve been made to rest at the Olympic village.

In a small room, on Chinese television, I’ve seen my team-mates win six gold medals so far. Chris Hoy, my equivalent in the men’s sprint, has already won two golds and looks a certainty for a third a few minutes after my race. It’s been a British procession, the culmination of years of work and planning, but I’ve just sat and watched. Sometimes I’ve hugged a pillow to myself, while staring at the screen alone, thinking, ‘Shit, shit, shit … if I don’t win I’m not going to be part of this team. Shit, shit, shit … I have to win to be part of this story. I need to win.’

Now, before I slide the mask across my face, the mask that tells Meares I’m going to blitz her, I allow myself to think once more of Scott. On the rollers I remember his last love letter to me. I cherish the fact that it was handwritten on a sheet of blue squared paper. Scott had also cut out some photographs of me winning World Cups and World Championships – just to remind me that I’m pretty good at riding fast. He wanted me to remember that I’m the world sprint champion and I’ve beaten Anna Meares often enough. I can beat her again.

Scott’s words resonate in my head. I linger over his suggestion that I put myself through this trauma for three reasons. I endure the pain and strife because I’m doing this for the people who have loved and supported me so long. I’m doing this for my family, my friends, my coaches and, of course, for Scott. I also go through the ringer, from the rollers to the track, just for myself. I’m twenty-seven years old. I’ve poured my whole adult life into preparing for this moment. So I’m out to win gold for the people who love me and, yes, I want it for me too.

The third and more shadowy group are now in my mind. I will soon blank every single one of them and home in on Meares. But Scott told me, in his beautiful letter, that I should also go out there and push myself to the edge of my ability so that I can show all those people who didn’t believe in me during the long and lonely years. They doubted me. They dismissed me. They hurt me. It’s time I show them how wrong they were about me. It’s time I make them change their minds forever about me.

Suddenly, I see Frédéric Magné, the coach who made me cry so hard in Athens. Fred, whom I liked and respected so much when I worked with him for eighteen months at his sprint academy in Aigle, walks around the pits. He’s training the Chinese girls now and, specifically, another great rival of mine, Guo Shuang, who has just won the bronze medal race. Fred keeps drifting in and out of my eye-line but, now, I hold him in my gaze. He looks at me, getting ready to go out and seize Olympic gold.

I look right through him as if he’s not even there.

I can feel the resentment surging inside me. Staring through Fred, it’s as if I’m looking beyond him to that moment when he tore into me in Athens. His words cut me far deeper than my own knife had done. He seemed to have no awareness of the pain he caused me.

On the rollers my legs keep turning, moving faster and faster. My face is utterly impassive. I am not the same frightened and confused girl I was in Switzerland. I am not the same girl who took a Swiss army knife and used it on herself because the cutting was less hurtful than the darker pain inside. Who would have thought it? Who would believe that distressed girl, who harmed herself, would make it all the way to an Olympic final?

The Smashing Pumpkins, singing of pink ribbon scars and cleansed regret, remind me of that past confusion.

Away from Fred I see another man who ripped into me. Martin Barras, a French-Canadian who is now Australia’s sprint coach, ridiculed me when he held a similar position within British cycling. He took just one look at me when I joined the sprint programme in Manchester in 2001 and decided I was far too slender and girly and weak to ever make it in the world of professional cycling. ‘Miss Victoria,’ he said, ‘I’m going to find you very annoying.’

Well, Martin, here I am, seven years later. I’m one up on your girl, Anna Meares. She has the squat and powerful physique that you believe is a pre-requisite for success on the sprint track. Anna looks like she could flatten me with just one swipe of a killer thigh. She’s got the force, too, in her backside to make someone like Martin think she should smash a frail and vulnerable little girly like me every time.

I feel like I am about to start growling on the rollers as my gaze switches from Fred to Martin, from one doubter to another. My uncomplaining legs pump just a little harder as the darkness descends. I’m going to show you, Fred, I swear to myself. I’m going to show you, Martin, I swear again.

I’m not just going to beat Martin’s big hope, Anna Meares. I am going to crush her. I want to annihilate her not just by winning the Olympic final but by demolishing her by an entire straight. I want to obliterate her hopes with the fastest time a woman has ever ridden in a sprint match.

I’ve never felt like this before. It’s an incredible emotion. I turn tingly with excitement. Adrenalin courses through me. There is so much tension and expectation in these last minutes. It seems like I’ve been touched by fate.

I think to myself: ‘God, this is going to happen. I am going to become the new Olympic champion.’

On the rollers, of course, I have no idea of the terrible pain and disappointment that will soon follow. I just know that victory, in this race, is mine. I start to lose myself to the sprint. I turn as powerfully blank as my pumping legs.

I feel ready. I feel like, at last, I’m going somewhere fast …