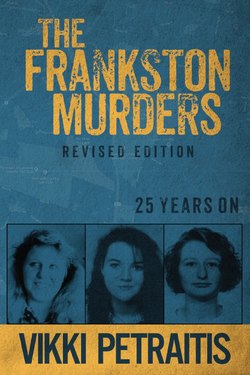

Читать книгу The Frankston Murders - Vikki Petraitis - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеI began writing The Frankston Murders back in 1993 when people living in the bayside suburbs were terrified because we had a serial killer in our midst. At that time, I had written my first book called The Phillip Island Murder and was working on my second true crime book which was a collection of short stories from different areas of the police force.

I had already spent quite a bit of time with the police at Frankston gathering material and was scheduled to meet with officers from Frankston’s community policing squad. It was a Friday afternoon in July and I remember walking into a solemn atmosphere as the officers were expressing their concern for the missing mother of a newborn baby.

Debbie Fream had been cooking dinner for a friend the night before, when she dashed out to the local shops to buy milk, and vanished.

At that early stage, it was a community policing squad issue because it was assumed Debbie must have suffered some kind of post-natal depression and taken herself off somewhere. It was the only thing that made sense, because young mothers didn’t simply vanish off the face of the earth.

As I arrived, talk in the squad rooms had taken a worrying turn because Debbie’s car had been discovered near a local hall with the driver’s seat pushed right back. Debbie was short and drove with the seat pushed forward. Had someone taken her and then driven her car?

Adding to the growing concern were reports that drivers along the Frankston Dandenong Road had seen a car similar to Debbie’s flashing its headlights at oncoming cars around the time she disappeared.

After an anxious four-day wait, Debbie’s body was found dumped on a remote road at the back of Carrum Downs.

Her death was quickly linked with the murder, the month before, of 18-year-old Elizabeth Stevens, and with other murders in the Frankston area over the previous years.

It didn’t take long for newspaper headlines to start screaming that Frankston had a serial killer and people started to panic. I lived a couple of suburbs away and witnessed the panic like everyone else.

Detectives in long dark coats knocked on our doors asking if we’d noticed anything odd, seen anything that could help. Police flooded into the area, transferred from duties elsewhere on the hunt for the serial killer.

Finally came the night that I knew I had to write this book. I was doing a police ride-along with a sergeant in Frankston and we arrived for the nightshift around 10.30pm. We were met at the back gate by the group of stalwart smokers puffing away under the spot light at the back door of the big new police station.

‘Another one’s gone missing,’ one of the cops told us.

‘Right under our bloody noses,’ said another, shaking his head hopelessly.

‘What kind of girl is she?’ asked the sergeant.

It was a question that would make every feminist shudder; as if the kind of girl made a difference. I soon realised, though, that the question was in fact cop-speak for whether she was a likely runaway or not.

The answer? ‘Nah, she’s a good kid. Just never came home from school.’

Not long after we entered the police complex, news came of a body found off a pathway between two Frankston golf courses.

And so it was that I found myself alone in the backseat of a police car, in the car park of the school that adjoined the track where the body had been found.

I stayed there taking notes while the low-flying police helicopter shone its night-sun over where the body lay. In the small hours of the morning I waited and watched the shadowy police officers doing what they do, and wondering about this killer who seemed uncatchable.

Where was he now? Was he gloating? Was he watching the news for glimpses of the carnage he had caused; laughing at the cops who couldn’t catch him?

How many more women would die before they caught him?

When the police finally returned to the car to head back to the police station, the sergeant warned me that I couldn’t use the notes I had taken, or talk to the press. When they caught the bastard, everything had to be done by the book.

Sure, I said. I wasn’t a journalist; I didn’t want to race my notes off to the nearest newspaper anyway. I was a true crime author, and if this story was to be written, it would need more than just headline-grabbing prose. It would need to be measured and tell a bigger story. It would need to talk about not only what the serial killer did, but about what he took from us. It would need to explore the aftermath of such a killing spree on the families affected and the community.

And so, after the key clanged on the killer’s jail cell at the end of 1993 I set about documenting the events as thoroughly as I could. The result was this story.

What do we get from looking at cases like this? What can we learn about ourselves and our community? For one thing, an atrocity like the Frankston murders is always counter-balanced by the community response. While nothing replaces what Denyer took, and nothing repairs the families who were forever altered with loss, the community spirit swells when it is needed, both in support and in the voice of outcry against the justice system which didn’t seem to recognise that a 30-year minimum sentence just wasn’t enough.

Another thing we learn from a close examination of Paul Denyer is that there are some people in our community who do not operate with the same sense of right and wrong as we do.

Some people just don’t get it; they are not on the same wavelength as everybody else. At no time did Denyer indicate remorse or regret for what he had done. It would appear that he is incapable of such feelings.

I remember chatting to a man at a talk I gave after this book was first published. He told me that his wife felt guilty about Natalie Russell’s death because they knew the Russell family, and his wife would sometimes give Natalie a ride home from school. On the day Denyer murdered Natalie, the wife had been caught up and didn’t drive past at the normal time. While the man was telling me this, it suddenly occurred to me that so many people felt guilty about all the victims.

If only, they thought. If only I had picked Natalie up; if only Debbie had remembered to buy milk earlier; if only Elizabeth had caught a different bus; if only…

Ironically, the only person who didn’t feel guilt, was the only person who should have, Paul Denyer.

And lastly, perhaps the Denyer case has taught us that we need to rethink laws about serial killers. They are a danger to society and most studies suggest they are incurable. Denyer was granted a 30-year minimum sentence because he hadn’t offended before. This is pretty standard for serial killers and needs to be recognised in sentencing.

A 30-year non-parole period sounded substantial back in 1993, but on the 25th anniversary, that time is nearly up. It’s certainly something to think about.

Vikki Petraitis

2018