Читать книгу Inside the Law - Vikki Petraitis - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3. A Book in the Hand

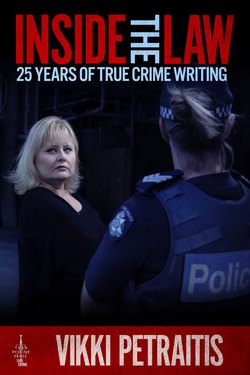

ОглавлениеPaul Daley and I at the launch of The Phillip Island Murder.

It took two years to write The Phillip Island Murder from start to finish. I remember when the book was hot off the presses, I stood at the letterbox with my advance copy. It was a small book for so much work but holding it in my hand made every moment worthwhile.

First came the book, then came the publicity. I was 27 years old and largely ignorant of the process of publishing. Until then, I thought it was a coincidence that when a new book came out, the author would appear on the radio or TV. (I know, right.)

My rude awakening came when I was asked to go on the Bert Newton morning show. Bert Newton was the TV legend of my childhood. I was so nervous, I hardly remembered my own name, let alone what I was there to talk about. It didn’t help that I was left in the green room watching the show on a monitor with Bert’s wife Pattie Newton who was there to surprise Bert at the end of the show because it was his birthday. When I was announced as ‘coming up after the break…’ she turned to me and said, ‘You should be on set!’

They’d forgotten to come and get me!

In a flurry of hurrying up a flight of stairs and someone shoving a microphone pack into my belt and telling me not to be nervous because there were only five million people watching, I was plonked onto a couch opposite Bert, heart pounding, hoping not to have a heart attack. Luckily, I knew the case so well after living it for two years, I was able to answer questions on autopilot. I watched a tape of the interview later on and I didn’t come across as nervous as I felt. Thank goodness.

Radio was the same. Before doing my first-ever radio interview, I nervously asked Melbourne radio interviewer Jon Faine (another legend of the airwaves) what he was going to ask me. He snapped back that I would find out when we were on air. He’s lucky I didn’t faint.

There was no training or advice for a publicity newbie. I just went where I was told and tried not to sound stupid. My family recorded each interview on cassette tapes, but I rarely listened to them afterwards. It avoided those do-I-really-sound-that-annoying? moments.

Not surprisingly, a young primary school teacher turned true-crime writer was a bit of a novelty and a couple of newspapers featured articles, not only about the book, but me as well. As fun as my 15 minutes of fame was, I always felt that I was just the storyteller; it was the stories I told that were important, not me. Maybe I needed to get a T-shirt with the slogan: ‘Look away people. Nothing to see here.’

The Phillip Island Murder was released in the middle of 1993. I held a launch party at my house, and Paul Daley and I posed proudly with our little book. On 11 July 1993, The Sunday Age featured the book in a two-page spread. We later heard that The Sunday Age was not sold on Phillip Island that weekend. The book wasn’t available on the Island either. Locals had to cross the bridge to get their copy. It didn’t surprise me. While some people had been happy to be interviewed when we were writing the book, others had been most unwilling. Paul and I had both noticed a palpable fear among the locals. Being non-Islanders, it was hard to understand what they were afraid of.

The story was quickly picked up by a show called Hard Copy who wanted to film a segment on it. Before I could blink, there was a TV crew in my lounge room, and I began my learning curve about how things were done in TV land. When I told the crew that the Camerons were unlikely to be interviewed since they had refused our requests, one of the crew said, ‘Oh that’s okay. We’ll get some footage of them slamming the door in our face.’

First illusion shattered.

I’d always thought door-slammings were genuine attempts to interview people, not contrived attempts to get people to slam doors. In the end, they didn’t approach the Camerons.

The minute the story went to air, my home phone started ringing. That night, I learnt there were people in the world who watched TV with a telephone book by their side, ready to look up the numbers of random people they saw on TV and ring them. My address was also in the phone book and I realised that wasn’t a good idea. The next day I organised a silent phone number.

While the publicity phase of a book is the only part most people see, for the writer, the opposite is true. Two years of interviewing people and sitting in front of a computer ends in a blaze of cameras, then the world rights itself again and a couple of weeks later, you’re back where you started.

I had learnt so much from Paul Daley about writing, but on my next book, I would fly solo. I still felt I needed all the help I could get. I saw an advertisement at a community centre for a creative writing group run by Dr Katherine Phelps and enrolled, even though it meant more nights out in an already busy life. Writers will understand the compelling need to improve our craft that seemed more important than most other things.

And so, for a while, I taught kids during the day, and became a student myself in the evening. Dr Katherine Phelps was an amazing teacher who taught me how to add the senses to description, and how to make writing come alive.

The young true crime writer.

Katherine was a great storyteller. Every time we had to write a description of something, she would write too and share hers with the class. As a teacher, I found this kind of modelling wonderful and tried to do this with my students.

My daughter was nearly five years old when the book came out. At some point during my writing of the Phillip Island book, she had grown old enough to pick up on things without me realising. One day, someone asked her what her mummy was writing about. To my horror she said something like: ‘Well, Vivienne killed Beth and jumped off a bridge.’

If there were hashtags back then, mine would have been #parentingfail. Note to self: stop talking about your book in front of your kid; she’s listening!

Another clash of worlds happened when the famous Aussie actor Norman Yemm came to school to talk to the kids. He mentioned being on the Bert Newton show and my kids – Grade 3s from memory – excitedly said, ‘Mrs Petraitis was on Bert Newton too!

Norman Yemm turned to me and said in his wonderfully expressive voice: ‘Fellow thespian?’

The kids gasped, thinking he’d just asked if their teacher was a lesbian.

As I grew more confident with my writing, I looked for a new project. Almost every cop I spoke to while researching the Phillip Island book, said the same thing: once this book is done, come back; we have plenty of stories.

I decided to do a compilation of short cases about the experiences of police officers. I contacted various departments of the Victoria Police and asked officers for their best story. It was a good tactic because their bar is pretty high. Stories that stood out to cops often had unusual elements that touched their hearts. And if it touched them, it would touch the reader.

I wrote a couple of stories and sent them to a publishing house called Victoria Press. They rang me the next day and said they were interested in the book – which eventually became Victims, Crimes and Investigators – so I kept writing.

And my eyes were opened to the world.

I learnt that some people didn’t play by the rules. I learnt that cars can be deadly weapons, and I learnt that a lot happens after most of us are safely tucked in our beds at night. Each new story taught me something about life and something about the craft of writing.

One thing led to another, just as stories linked in unexpected ways. The observant reader of my books might have noticed some of these connections. CIB detective Jack McFayden, who searched the Phillip Island bridge after Vivienne went missing, gave me a story for the second book. So did crime scene examiner Sergeant Brian Gamble, who worked the crime scene at Phillip Island.

Gamble had a case he worked on where a body was found in a shallow grave on the Rye back beach, cut into pieces and wrapped in neat packages. Unlike CSI on TV, crime scene examiners don’t do the investigation. So when he told me about the gruesome crime scene he encountered that cold day on the beach, I asked him for more details.

He shrugged. ‘You’ll have to talk to the detectives,’ he said.

And so I did.