Читать книгу Adventure Tales #5 - Vincent 1886-1974 Starrett - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

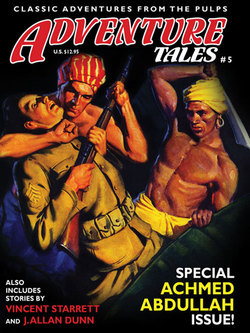

ОглавлениеTHEIR OWN DEAR LAND, by Achmed Abdullah

OMAR THE BLACK sighed—and grinned a little too—at the recollection.

“There was Esa, the chief eunuch, yelling at me,” he said to his twin brother Omar the Red. “And there was Fathouma, the woman I had, if not loved, then at least left, smiling at me! Ah—I felt like a nut between two stones. Can you blame me that I sped from the place?”

He described how, with the help of crashing elbows and kicking feet, he bored through the crowd; how at a desperate headlong rush, he hurtled around a corner, a second, a third, seeking deserted alleys, while behind him, men surged into motion.

There was then pursuit, and the chief eunuch’s shouts taken up in a savage chorus:

“Stop him!”

“What has he done?”

“Who cares? Did you not hear? A hundred pieces of gold to the man who stops him!”

“Money which I need!”

“No more than I! Money—ah—to be earned by my father’s only son!”

Well, Omar the Black had decided, money not to be earned, if he could help it. He was not going to be stopped, and delivered up to the chief eunuch. It would mean one of two things: an unpleasant death or a life even more unpleasant.

For he knew the chief eunuch of old—knew that the latter, who had been fiercely jealous of him during the days of his affluence and influence at the court of the Grand Khan of the Golden Steppe, had always intrigued against him, always detested him, always tried to undermine him. And here, tonight, was Esa’s chance.

A chance at bitter toll!

Either—oh, yes!—an unpleasant death or a life yet more unpleasant. Either to be handed over by the eunuch to the Grand Khan; and then—the Tartar considered and shuddered—it would be the tall gallows for him, or the swish of the executioner’s blade. Or else—and again he shuddered—his fate would rest with Fathouma, the Grand Khan’s sister.

And—ai-yai—the way she had peered at him through the fluttering silk curtains of the litter! The way she had smiled at him! Such a sweet, gentle, forgiving smile! Such a tender smile!

Allah—such a loving smile!

Why—this time she might be less proud, less the great lady. Might insist on carrying out their interrupted marriage-contract. And what then of this other girl, this Gotha? A girl—ah, like the edge of soft dreams—a girl whom he loved madly.…

He interrupted his thoughts.

What, he asked himself, as his legs, one sturdy and sound and the other aching rheumatically, gathered speed, was the good in thinking, right now, of Gotha? First he would have to find safety—from the Grand Khan’s revenge no less than from Fathouma’s mercy.

Faster and faster he ran—then swerved as a man, whom he passed, grabbed his arm and cried:

“Stop, scoundrel!”

Omar shook off the clutching fingers; felled, with brutal fist, another man who stepped square in his path; ran still faster, away from the center of the town, through streets and alleys that were deserted—and that a few moments later, as if by magic, jumped to hectic life.

Lights in dark houses twinkled, exploded with orange and yellow as shutters were pushed up. Heads leaned from windows. Doors opened. The coiling shadows spewed forth people—men as well as women. They came hurrying out of nowhere, out of everywhere.

They came yelling and screeching: “Get him!”

“Stop him!”

“There he goes!”

“After him!”

The pack in full cry—two abreast, three, four, six abreast. Groups, solitary figures!

A lumbering red-turbaned constable, stumbling out of a coffee-shop, wiping his mouth, tugging at his heavy revolver.

Shouted questions. Shouted answers:

“What is it?”

“What has happened?”

“A thief!”

“No! A murderer!”

“Three people he slew!”

“Four! I saw it with these eyes!”

“Ah—the foul assassin!”

And sadistic, quivering, high-pitched screams: “Get him!”…“Catch him!”…“Kill him!”

Ferocious gaiety in the sounds. For here was the cruel, perverted, thrill of the man-hunt.

“Get him!”

“Kill him!”

“Quick, quick, quick! Around the next corner! Cut him off!”

Swearing, shrieking. Throwing bricks and pots and clubs and stones. Pop! pop! pop!—the constable’s revolver dropping punctuation marks into the night. And on, on, the sweep of figures. And Omar the Black running, his lungs pounding, his heart beating like a triphammer; darting left, right, left, right—steadily gaining on his pursuers, at last finding temporary refuge at the edge of town, in the old cemetery, among the carved granite tombstones that dreamed of Judgment Day.

There, stretched prone on the ground, he turned his head to watch the mob hurrying on and past on a false trail. He listened to the view-halloo of the chase growing fainter and fainter, finally becoming a mere memory of sound.

Then, slowly, warily, he got up. He looked about.…

Nobody was within sight.

So he doubled on his tracks and left Gulabad from the opposite direction, hag-ridden by his double fear—of the Grand Khan’s revenge and of Fathouma’s loving tenderness.

To put the many, many miles between himself and this double fear, this double danger—that is what he must do, and do as quickly as possible. His resolve was strengthened by the knowledge that money was sultan in High Tartary as anywhere else in the world; that the tale of the rich reward which had been offered for his capture—a hundred pieces of gold—would be round and round the countryside in no time at all, and so every hand there would be against his, and every eye and ear seeking him out.

Therefore Omar the Black traveled in haste and in stealth. At night he traveled, hiding in the daytime, preferring the moors and forests to the open, green fields; taking the deer- and wolf-spoors instead of honest highways; plunging to the knee—and his rheumatic leg hurting him so—at icy fords rather than using the proper stone bridges that spanned the rivers; avoiding the snug, warm villages where food was plentiful and hearts were friendly. And living—as the Tartar saying has it—on the wind and the pines and the gray rock’s lichen!

Footsore he was, and weary; and wishing: “If only I had a horse!”

A fine, swift horse to take between his two thighs and gallop away. Then ho for the far road, the wild, brazen road, and glittering deeds, glittering fame! Yes—glittering fame it would be for him; and he hacking his way to wealth and power; and presently returning to Gulabad.

No longer a fugitive, with a price on his head and the Grand Khan’s revenge at his heel, but a hero, a conqueror; the equal—by the Prophet the Adored!—to any Khan.

Omar was quite certain of his ultimate success, and for no better or, belike, no worse reason than that he was what he was: a Tartar of Tartars—the which is a thing difficult to explain with the writing of words to those who do not know our steppes and our hills.

Perhaps it might best be defined by saying that his bravery overshadowed his conceit—or the other way about—that both bravery and conceit were overshadowed by his tight, hard, shrewd strength of purpose, and gilded by his undying optimism. Anyway, whatever it was, he had it. It made him sure of himself; persuaded him, too, that some day Gotha would be his, so sweet and warm and white in the crook of his elbow.

The imagining intoxicated him. He laughed aloud—and a moment later grew unhappy and morose. Only a fool, he told himself, will grind pepper for the bird still on the wing.

Not a bird, in his case, but a horse. A horse was the first thing he had to have for the realization of his stirring plans. Without a horse, these plans were useless, hopeless—as useless and hopeless as trying to throw a noose around the far stars or weaving a rope from tortoise-hair.

Yes, the horse was essential. And how could he find one, here in the lonely wilderness of moor and forest?

Thus, despondent and gloomy, he had trudged on. Night had come; and the chill raw wind, booming out of the Siberian tundras, had raced like a leash of strong dogs; and hunger had gnawed at his stomach; and thirst had dried his throat; and his leg had throbbed like a sore tooth. “Help me, O Allah, O King of the Seven Worlds!” he had sobbed—and as if in answer to his prayer, he had heard a soft neighing, had seen a roan Kabuhi stallion grazing on a short halter, had sneaked up noiselessly, had unhobbled the animal and been about to mount.… And then:

“By Beelzebub,” he said now, angrily, to his twin-brother, “it had to be yours!”

Again he sighed.

“Ah,” he added, “am I not the poor, miserable one, harried by the hounds of fate!”

* * * *

Omar the Red looked up.

“Not poor, surely,” he remarked.

“What do you mean—not poor?”

“Unless, in your flight, you lost the jewels which you took from the rich Jew.”

Omar the Black jumped up.

“As the Lord liveth,” he exclaimed, “I had forgotten them!”

Anxiously he tapped his loose breeches. There was a pleasant tinkle, and a few seconds later a pleasant sight as he brought out a handful of emeralds and rubies that sparkled in the moon’s cold rays.

Then once more he became despondent.

“What good,” he asked, “are these jewels to me? As much good as a comb to a bald-headed man. Why, not even were you to give me your horse—”

“Which, decidedly, I shall not.”

Omar the Black paid no attention to his brother’s unfeeling comment.

“No,” he repeated, “not even were you to give me your horse.”

For, he went on to say, Gotha was a slave in the harem of Yengi Mehmet, the Khan of Gulistan. The latter, according to Timur Bek, was as eager for money as a young flea is for blood. Therefore, before Omar the Black had a chance to leave his mark upon High Tartary and return to Gulabad, a hero, a conqueror, somebody else might covet the girl, might offer a great price for her—and Yengi Mehmet would sell her.…

He drew a hand across his eyes.

“Allah, Allah!” he cried. “What am I to do? Ah, if you could see this girl! As a garment, she is silver and gold! As a season, the spring!”

“So,” was the other’s impatient interruption, “you told me before—and bored me profoundly. The question is—you desire this girl?”

“As Shaitan, the Stoned Devil, the Accursed, desires salvation.”

“Very well. You shall have her.”

“But—how?”

“I shall help you”—Omar the Red paused. “For a consideration.”

“There would be,”—bitterly,—“a consideration, you being you.”

“There is, I being I—or for that matter, anybody being anybody. Therefore, if I help you to get your heart’s desire, will you—”

“Yes, yes! Anything! Put a name to it!”

“A dear name! A grand and glorious name! The old palace back home where you and I were born, which I lost to you—”

“In a fair fight.”

“Fair enough. I want it back.”

“Is that all? Help yourself.”

“Thanks. Only—I have not enough money. But you, with a tenth of these jewels, can pay off the old debts.… Listen!” He spoke with deep, driving seriousness. “Far have I wandered, astride a horse and on stout shoes, and too, at times, on the naked soles of my feet, fighting thy own fights—and other men’s fights—for the sport of it and a bit of loot. But over yonder”—he pointed north—“is the only place I have ever seen worth hacking sound steel for in earnest. And over yonder the one girl, Ayesha, worth loving. Ah—somebody. once told me there is no happiness in another man’s shoes, nor in another man’s castle, nor with another man’s wife. So—what say you—we go home, you and I, and live there—I with Ayesha and you with Gotha—”

“I—with Gotha? But—”

“Did I not tell you I would help you?”

“How can you?”

“I shall buy her for you.”

“What with—since you have no money?”

“But you have the jewels. And did not Timur Bek offer to arrange the matter with the Khan?”

“Yes.”

“There you are. Timur Bek will be your intermediary with the Khan—and I shall be your intermediary with Timur Bek. Hand over the jewels. I shall hurry to Gulabad, sell the jewels, talk to Timur Bek, have him buy the girl, then return here with her and—”

“No!” came Omar the Black’s loud bellow.

“No?”

“No, indeed!”

“Why not?”

The other smiled thinly.

“Would you leave meat on trust with a jackal.”

“In other words, you do not trust me?”

“Neither with the jewels, nor with the girl.”

“And perhaps,” was the shameless admission, “you are wise. But—well, there is another way.”

“Yes?”

“We shall both go to Gulabad.”

“I—with a price on my head?”

“On your black-bearded head, don’t forget. But who, tell me, will recognize this same head—without the beard?”

“Oh”—in a towering rage—“dare you suggest that I should—”

“Shave off your beard? Right.”

“Impossible! Why, by the Prophet the Adored, this beard,”—he ran a caressing hand through it—“has been my constant and loyal companion in joy and in sorrow. It is the pride and beauty of my manhood.”

“The pride and beauty will grow again.”

For quite a while they argued, until finally Omar the Black gave in.

But he cursed violently while scissors and razor did their fell work. He cursed yet more violently when, having announced that the stallion was strong enough to carry the two of them, he was informed by his twin brother that such a thing was out of the question.

For, opined Omar the Red, here was he himself most splendidly clad as became a gentleman of High Tartary. And here was the other, in stained and odorous rags—a very scarecrow of a man. It would seem strange to people, whom they might meet, to see them in such an intimacy, astride the same horse.

Better far, he said, for the other to run sturdily in back of the stallion, with outstretched hand, like some importunate beggar crying for zekat! zekat! zekat!—alms for the sake of Allah.

He clapped his brother heartily on the back. “It will be safest for you,” he added. “Besides, you will see more of this fine broad world, walking on your two feet, than cocked high and stiff upon a saddle.”

Omar the Red laughed.

* * * *

So, on an evening almost a week later, did Timur Bek laugh, back in Gulabad, when—for at first he had not recognized him, with his beard shorn off—he learned that this smooth-cheeked man was Omar the Black.

“Here you are,” exclaimed Timur Bek, “with your face as soft as a girl’s bosom!”

He laughed more loudly. “Oh,” he cried, “if Gotha could see you!”

Omar the Black swallowed his anger.

“She is still here?” he demanded.

“And pining for you, I have no doubt.”

“And—your promise?”

“I have not forgotten it.”

Timur Bek went on to say that he was ready to open negotiations about the girl’s purchase with Yengi Mehmet. He would do it tactfully and drive as good a bargain as he could.

“I know, of course,” he added, “that you have the jewels.” He smiled. “The Jew, Baruch ben Isaac ben Ezechiel, made a great ado about it. Swore that nineteen tough Tartars, armed to the teeth, broke into his shop and assaulted him!”

“Nor,” said Omar the Black, “did he lie—exactly. For am I not the equal of the nineteen toughest Tartars in the World? Very well. My brother and I shall sell the jewels. Do you know a place—oh—a discreet place where we—”

“Can sell the jewels? Not necessary.”

“But—”

“The Khan likes precious gems as much as minted gold.”

“Still, he may suspect—”

“He will not listen to the evil voice of suspicion—if the jewels be rich enough. If they be rich enough, his left eye will look west, and his right east. Let’s have a look at the loot.”

The other reached into his breeches. He poured the gems in a shimmering stream on a low divan; and Timur Bek licked his lips. He said:

“It may take a good many of these trinkets to—”

“Nothing too much to buy me my heart’s desire. Here—take half the stones!”

Timur Bek coughed.

“There is also,” he said, “the matter of the money which I borrowed from the Khan, giving the little slave-girl, whom I love, as security. You were going to help me pay back the loan—remember?”

“I do. And I shall keep my word.”

“The sooner, the better—for you.”

Omar the Black frowned. “Eh?”

“This girl, you see, has the Khan’s ear. I need her assistance. Loving me as I love her, she is anxious to return to me. And so, unless I buy her back, I am afraid she—”

“Yes, yes, yes!” Omar the Black interrupted impatiently. “Here—take another fourth of the stones. Surely it will be enough.”

“Not quite.”

“But—”

“Thirty thousand tomans I borrowed. It will take the rest of the stones to—”

“All right!” with a sigh. “Take them all!”

Timur Bek’s hands were about to scoop up the jewels, when Omar the Red cried:

“Wait!”

He touched his brother’s knee.

“You are forgetting our agreement,” he told his brother. “You were going to use some of the treasure to pay off your old debts, so that we can return home and—”

“I have not forgotten.”

“Why—”

“Listen!” Omar the Black winked slowly at his twin brother. “That time I broke into the Jew’s shop, I was in a hurry. I took only half the jewels. The other half is waiting for you and me.”

He turned to Timur Bek:

“When will you speak to the Khan?”

“Tonight. At once.”

Timur Bek left his house. He went round the corner to the garden gate of Yengi Mehmet’s palace.

There, while night was falling thicker and thicker, wrapping the streets in a cloak of trailing purple shadows, he whistled: two high, shrill notes, followed by a throaty, fluting tremolo, like a crane calling to its mate.

There was silence.

He waited; listened tensely, then repeated the call—and the gate opened softly; and a small white-robed figure slipped out and rushed into his arms with a little cry of joy.

“O my beloved!”

“O soul of my soul!”

“O king!”

“O sweetmeat!”

They spoke in a whisper, at length. They laughed. They kissed. And presently Timur Bek returned to the roof-top of his house, where Omar the Black was pacing up and down impatiently, while Omar the Red was applying himself to a bottle of Persian wine.

“Well—?” demanded the former.

“I talked to my girl.”

“Not to the Khan?”

“She, as I told you, has the Khan’s ear. And it seems that he is willing to sell Gotha. But—”

“Is there a but?”

“Isn’t there always?” Timur Bek paused. “He is fond of her.”

“What’s that?”—excitedly.

“In a fatherly manner. Yes—as if she were his daughter. Therefore he insists that whoever buys the girl must marry her.”

“I—marry?”

“Yes. It is part of the bargain. You must marry her at once. Tomorrow evening, at the Mosque of Hassan. A simple ceremony, with no witnesses. The girl, being shy, insists on it.”

Omar the Black did not reply immediately.

Marriage, he reflected—as more than once, on his lawless path, his brother had reflected—meant bonds of steel. It meant the orderly homespun ways of life; meant—oh, all sorts of disagreeable things.… An end to freedom!

And it was on his tongue to exclaim: “No! Let Yengi Mehmet keep the girl!”

But he reconsidered as he thought of her—with her full red lips, and her brown hair as smooth as oil, and her gray eyes that seemed to hold all the secret wisdom, all the secret sweet mockery of womanhood.

Lovely! So very lovely!

He loved her.… Besides, coming to think of it, marriage was not necessarily the end. Bonds of steel, too, could be broken—by a strong and ruthless man.

“Very well,” he announced. “Marriage it will be.” And, severely, to his brother: “Let this be a lesson to you—to follow in my virtuous footsteps!”

“As virtuous,” remarked Timur Bek, “as mine own. For I too shall take a wife unto myself—the little slave-girl whom I love.”

“You have repaid your loan to the Khan?”

“Thanks to you, Great-Heart. Tomorrow morning my love and I are going away. Therefore if, for the time being, you and your bride and your brother would care to live in my house, you are welcome. There is food in the larder and wine in the cellar. And after all, with your jewels gone—”

“I shall be poor, I know.”

“Only,” chimed in Omar the Red, “until Baruch, the rich Jew, contributes another handful of gems.”

* * * *

Late on the following evening, Omar the Black, arrayed in some of his brother’s handsome clothes, went to the Mosque—an ancient and beautiful building raised on a flight of broad marble steps, its great horseshoe gateway covered with delicate mosaic arabesques in mauve and silver and heliotrope and elfin-green.

There the bride, wrapped from head to foot in three heavy white wedding veils, awaited him.

She saw his smooth cheeks. But she gave no more than a little start. For she had been warned of what had happened to his beard; and with or without his beard, she loved him—loved him dearly.

Slowly he walked up to her. He bowed—and so did she.

* * * *

Hand in hand they stepped before the green-turbaned priest, who united them in holy wedlock, according to the rites of Islam:

“Will you, O son of Adam, take this woman to wife—before God the One, and the Prophet the Adored, and the multitude of the Blessed Angels?”

“I will!”

“Will you, O daughter of Eve, take this man to husband—before God the One, and the Prophet the Adored, and the multitude of the Blessed Angels?”

“I will!”

Silence.… Omar the Black stared at his wife.

“Soon to be mine!” he whispered. “Soon—soon!”

Then there was the priest chanting a surah from the Koran in nasal, sacerdotal tones:

For the Merciful hath taught the Koran,

He created the male and the female,

He taught them clear speech,

He taught them desire and fulfilment.

An echo of His own creation.

So which of the Lord’s bounties would ye twain deny?

The sun and the moon in their courses,

And the planets do homage to Him,

And the heaven He raised it and appointed the balance,

And the earth He prepared it for living things.

Therein He created fruit, and the palm with sheaths,

And grain with its husks, and the fragrant herb,

And the male and the female of man and of beast.

So which of the Lord’s bounties would ye twain deny?

“Not I,” said Omar the Black to his wife, “to deny this particular bounty.”

She gave a happy little laugh; the priest finished; husband and wife salaamed toward Mecca; and then Omar took her to Timur Bek’s house, up to the rooftop beneath the stars.

There his brother was. He greeted the couple with loud shouts of:

“Yoo-yoo-yoo!”

But Omar the Black cut him short.

“Enough ‘yoo-yoo-yoo’ for the nonce,” he said. “This is the one moment—of many, many moments—when I can do without your company.”

So Omar the Red left—winking, in passing, at the bride. And a few seconds later, slowly and clumsily, since his hands trembled so, Omar the Black raised the three wedding veils one by one.

“Wah,” he whispered throatily, “you are all my dreams come true!”

Then, swiftly, he receded a step. For, with the moon laying a mocking silver ribbon across her features, he saw that the woman whom he had married was Fathouma, the Grand Khan’s sister, and not Gotha.

Omar stood there without speaking. He stared at her.

Even more faded she was than when he had seen her last; more gray the hair that curled on her temples; more sharply etched the network of wrinkles at the corners of her brown gold-flecked eyes. But still the same eyes—with the same tenderness in them, the same sweetness and simplicity, the same depth of feeling. Eyes that lit up as she said to him:

“You broke my heart, years ago, when you left me. But now, the Lord be praised, you have made it whole again.”

She walked up to him. And what could he do but take her into his arms?

“Last night,” she went on, “when Timur Bek sent me word through Gotha that you had come to Gulabad in search of me, that you wanted me—wanted me for wife—I almost swooned with the great joy of it. And it was so tactful of you to insist on a simple wedding, you and I”—he winced a little at her next words—“being no longer young, lest people ridicule us. Already Esa is on his way to tell my brother the news; and my brother, too, will be so very happy—”

She stopped for breath. She kissed him.

“And,” she went on, “I talked to my cousin, the Khan of Kulistan. He will make you a captain in the palace guard, although—” with a fleeting smile curling her lips—“he is a little angry at you.”

“Why?”

“Because of Gotha.”

“Oh!”

“He liked her, and,” she laughed—“more than merely liked her. Hayah—the old cat, though blind and lame, still hankers after mice! And you, like the generous soul you are, giving all your jewels to Timur Bek, so that he could pay back to Yengi Mehmet what he owed him, and free Gotha, and marry her!”

He gave a start.

“You said—marry?”

“Did you not know? Very early this morning they went to the mosque and became man and wife. And now they are off to the steppe, the wilderness, to spend their honeymoon. For they are young. They can stand the rigor, the chill harsh winds, the open air. Well”—and again she smiled, while again he winced a little—“we are not young, you and I. But our love is as great as theirs—is it not, my lord?”

He did not reply immediately. He looked at her, with a long and searching look. And then—nor was it altogether because he feared her brother the Grand Khan, and knew that this time he would have no chance at all to get away, but also, and chiefly, because of a queer feeling in his soul, something akin to tender pity—he inclined his head and said: “There was never love greater than mine, O heart of seven roses!”

He was silent; and he thought, with supreme self-satisfaction: When I do a thing, by Allah and by Allah, I do it in style! It is the glorious way of me.

So he bowed gallantly in the Persian manner, his hand on his breast. He was about to kneel before her, and had already bent his left leg, when suddenly he felt a stabbing pain and gave a cry.

“Why! Oh,” was her anxious query

“What is the matter?”

“Nothing, nothing.”

“But I heard you—”

“A little pain—in my left leg.”

“A wound?”

“No. A touch of rheumatism.”

She shook a finger at him.

“Your own fault!”

“Eh?”

“Yes. To be up here on the roof late at night, in the cold, as if you were in your teens!”

“But—”

“You are old enough to have more sense! Off to bed with you—and a hot brick at your feet, and a glass of mulled wine to put you to sleep. Tomorrow we’ll leave this draughty house, and stay with my cousin the Khan of Gulistan, and—”

“Look—” he interrupted indignantly.

“Be quiet! I know what is good for you.”

Firmly she took him by the arm and led him down the stairs.

He did not resist. They passed Omar the Red’s room. And Omar the Black bit his lips and frowned as he heard a faint, “Yoo-yoo-yoo!” heard, a moment later, something which sounded, suspiciously, like laughter.

* * * *

IT cannot be said that, during the days that followed, Omar the Black was exactly unhappy. In fact, though he hated to admit it, he was enjoying life.

There was his wife. Faded, sure enough, and wrinkled. Not lovely at all, not the one to quicken a man’s heartbeat and set his flesh to aching. On the other hand, she was so kindly, so very, very kindly—and so strangely humble when, frequently, she said to him:

“You bring me great happiness. I love you, O best beloved!”

He would kiss her gently; lying like a gentleman, and after a while not lying at all, though he thought he did, he would reply:

“So do I love you, O delight!”

Furthermore—oh, yes, Fathouma was right—he was no longer in his teens, no longer eager to travel the hard road, with ever danger and death lurking around the corner. And it was pleasant to be once more, as formerly at the court of the Grand Khan of the Golden Steppe, a man of fashion, dressed in cloak and breeches of handsomely embroidered, Bokharan satin, and hose of gossamer silk, and boots of soft red leather, and a voluminous turban that had cost fifty pieces of silver—and always a deal of money clanking in his breeches, what with his captain’s pay and his wife’s generosity—and the work quite suiting his fancy.

Indeed, Omar did no work to speak of. Except that, as a captain in the service of the Khan of Gulistan, he would mount guard at the palace every forenoon for a leisurely, strolling hour or two, swapping yarns and boasts and lies with the other tall captains. And in the afternoons he would whistle to his tawny Afghan hound and stalk through the streets and bazaars, buying whatever he wished, and once in a while getting into a row because of insult real or, more often, imagined.

And in the evenings he would go on an occasional riotous drinking-bout, rolling home late and noisy—and Fathouma would be waiting for him, would cool his throbbing temples with scented water, nor give him the sharp edge of her tongue, but warn:

“You must be careful, best beloved. A man of your years—”

He would flare up.

“What do you mean—a man of my years?” he would demand. “Why, my heart is the same as ever it was, keen and lightsome! And my soul has the same golden fire, and my joints are still greased with the rich grease of youth, and—”

“Of course,” she would agree soothingly. “And yet you look a little tired, and so you had better have your breakfast in bed tomorrow. And here”—stirring a cup that held a steaming, dark, strong-smelling broth—“some tea of bitter herbs for your stomach.”

“No, no!”

“Yes, yes! Drink it at one swallow, hero, and it will not taste so bad.”

He would sigh—and obey.

He would, to tell the truth, feel better for it the next day, and get up later and later as morning succeeded morning.

And as time progressed, moreover, Omar went on fewer drinking-bouts; and, gradually he became less, eager at smelling out insults and picking quarrels with all and sundry. In fact, the only quarrel which he had—and carefully nursed—was with his brother.

It was the latter, he would reflect, who by persuading him to return to Gulabad, had been responsible for everything: his marriage as well as the loss of his fine black beard. And while, a little grudgingly, he might forgive him the marriage, he could not forgive the matter of the beard.

It had grown again—and rapidly—oh, yes! But thanks to the shaving, it was not as silky as formerly; and two gray hairs sprouting for each one he plucked out; and he, with his wife knowing it, rather embarrassed at using gallnut dye.

And furthermore, the mocking way his brother, that night after the wedding, had yoo-yoo-yooed and laughed!

No, no—he could not forgive him.

Therefore when Omar the Red called at the palace, asking his twin brother to fulfil his side of the agreement—to supply the cash for settling the old debts and help him get back to the castle and to Ayesha—Omar the Black raised an eyebrow.

“Do you expect me, an honorable Tartar gentleman,” he demanded, “a captain in the Khan’s service, to take part in such a wicked enterprise as robbing a shop? Ah—shame on you!”

“We don’t have to rob the shop.”

“Then how—”

“You are rich.”

“I am not.”

“But—”

“My captain’s pay is a mere pittance.”

“Your wife—”

“Has plenty. Yes. And,”—self-righteously,—“it would never do for a gentleman to accept money from a woman. Surely even you know that.”

Then, when the other grew angry and abusive, Omar the Black pointed to the door:

“Begone, O creature!” he shouted.

He instructed the palace servants that hereafter his twin brother was no longer to be admitted; and when Fathouma, who had heard him give the order, argued with him, he told her:

“You do not know my brother. Always, since his early childhood days, he has been a most lawless and sinful person, has always tried to lead me down the crooked road of temptation. He, I assure you, is not the proper companion for the like of me. And his way with the women—to kiss and ride away—shocking, shocking!”

Hypocritical? Not really. Or if he was, he did not know it.

Indeed, somehow, he meant what he said; began to fancy himself as a most sober and respectable citizen.

* * * *

No longer did his heart leap and skip like a gay little rabbit across the land whenever he beheld a new face, a young face, a pretty face. And one day when Fathouma mentioned that Timur Bek and his bride were expected home from their honeymoon—and what about entertaining them at dinner?—he shook his head.

“No,” he said.

“But—isn’t Timur your friend?”

“He is. But Gotha—”

“Yes?”

“A toothsome morsel, I grant you. Only—inclined to be flighty.”

“I don’t think so.”

“I know. Why, the very first time I saw her, she gave me the quirk of the eye. She asked me, if you want blunt speech—”

“Please! Not too blunt!”

“You are quite right. It would not be fit for your ears. Anyway, I would have none of her. For by the Prophet, I have always followed the white road of honor—naturally, being what I am. Besides, was not my friend Timur Bek in love with the young person? So, as you know, I let him have my jewels, so that he might buy himself his heart’s desire.”

He smiled benignly; went on in resonant and rather unctuous accents: “The Lord’s blessings on them both!”

Maybe Omar the Black believed that he spoke the truth. Maybe Fathouma did likewise; and maybe, being as clever in one way as she was simple in another, she did not—though without letting on.

For she loved her husband. She loved his very failings, and defended them, even to herself. She was happy—and happiest when, more and more frequently, he would spend the night at home and they would be alone; when he would sit by her side, pleasant and jovial and companionable, and tell her tales of his past life, his past prowess and bravery, his past motley adventures, east, north, south, west.

The love in her brown, gold-flecked eyes would enkindle his imagination. And—oh, the clanking, stirring tales he would tell then:

“The pick of the lads of the far wide roads I was, with ever my sword eager for a bit of strife, ever a fine thirst tickling my gullet, ever the bold, bold eyes of me giving the wink and smile at the passing girls, and they—the dears, the darlings!—giving the same wink and smile straight back at me—”

He would interrupt himself.

“That was,” he would add, “before I met you.”

“Of course.”

She would laugh. She was not jealous of the past, being wiser than most women. Also—oh, yes, she was clever—the very fact that his mind was dwelling more and more on former days and former deeds, proved to her that he was getting old and ready to settle down—which was as she wished.

And so late one afternoon when—it happened rarely nowadays—Omar the Black had gone to split a bottle or two with a boon companion, Fathouma decided that she would surprise him, would buy him a present: the handsomest carved emerald to be had in Gulabad.

She put on her swathing street veils and called to one of the lackeys, a Persian, who had recently been hired and who was a most conscientious servant—always present when he was needed and ready to do her bidding:

“Hossayn!”

He salaamed. “Heaven-born?”

“I am going to the bazaar to do some shopping. Come with me.”

“Listen is obey!”

Again he salaamed. He led the way out of the palace, crying loudly:

“Give way, Moslems! Give way for the Heaven-born, the Princess of High Tartary!”

He stalked ahead, clearing a path with the help of a long brass-tipped stave.

Fathouma followed. She was excited, elated. Ah, what an emerald she would buy her lord! She tripped along. And she did not know that, as they passed a dark postern, Hossayn exchanged a cough and a fleeting glance with a stranger who stood there hidden in the coiling, trooping shadows. Nor could she know that several days earlier Hossayn had been buttonholed on the street by this same stranger, who had spoken to him at whispered length and taken him to a tavern.

There, over glasses of potent milk-white raki, they had continued the conversation. There had been spirited haggling and bargaining. Finally with a sigh, the other had well greased the Persian’s greedy palm, giving him whatever gold and silver coins remained in his waist-shawl. He had added, for good measure, a couple of rings and a dagger.

He had leaned across the table, had asked:

“Do you know what I am thinking?”

“Well?”

“I am thinking,”—in a purring voice,—“that I have three more daggers, not as handsome as this but quite as sharp—and thinking, also, that, should you deceive me, yours might be a fine throat for slitting.”

The Persian had turned pale.

“Do not bristle at me, tall warrior!” he had begged. “I—deceive you? Never!”

“Of course not.”

“Only—”

“Only?” threateningly.

“I am not the only servant. Nor can I tell when the Heaven-born will—”

“I know. And I do not demand the impossible. All I expect you to do is to be attentive to her, to make a point of hovering near, being watchful.”

He muttered instructions; and the Persian inclined his head.

“I understand.”

So there was now, in passing, the glance, the cough—and once more:

“Give way, Moslems! Give way for the Heaven-born, the Princess of High Tartary!”

The people gave way as well as they could. But as Fathouma and the lackey approached the Street of the Western Traders, where the jewelers displayed their precious wares, the alleys and squares and marketplaces became ever more packed with milling, moiling, perspiring humanity, not to mention humanity’s wives and children and mothers-in-law and visiting country cousins.

For today—and as it turned out, it was a lucky stroke of fortune for the stranger who had left the postern and was following the two as closely as he could—was a great Islamic festival: the day preceding the Lelet el-Kadr, the Night of Honor, the anniversary of the blessed occasion when Allah, in His mercy, revealed the Book of the Koran to His messenger Mohammed.

A most solemn occasion, the Lelet el-Kadr—it being the night when the Sidr, which is the lotus tree and which bears as many leaves as there are human beings, is shaken in Paradise by the Archangel Israfel, and on each leaf is inscribed the name of a person who will die during the coming year, should it drop.

* * * *

Small wonder that strong, personal interest is behind the prayers after sunset. Small wonder, furthermore, that all lights are extinguished—lest dark and evil djinn find their way up to Paradise and nudge the Archangel, startling him and causing him to shake down the wrong leaf.

Small wonder, finally, that on the preceding day there should be merry-making—a fit prelude to the Night of Honor, the Night of Fear, the Night of Repentance.

So here in Gulabad as in the rest of the Islamic world, gay throngs were everywhere, people of all High Tartary, with here and there men from the farther east and south and north and west—Persians, Afghans, Chinese, Siberians, Tibetans, even men from distant Hindustan and Burma, come across mountains and plains to fatten their purses on the holiday trade.

Doing well, making handsome profits.

For all were ready to spend what they could—and could not—afford. All were enjoying themselves after the Orient’s immemorial fashion, resplendently and extravagantly and blaringly.

The men swaggered and strutted, fingering daggers, cocking immense turbans or shaggy sheepskin bonnets at rakish devil-may-care angles. The women minced along, rolling their hips and, above their thin, coquettish face-veils,, their eyes. The little boys tried to emulate their fathers in swaggering and strutting; to emulate each other in the shouting of loud, salty abuse. The little girls rivaled the other little girls in the gay, pansy shades of their loose trousers and the consumption of greasy, poisonously pink-and-green sweetmeats.

There were jugglers and knife-tossers, sword-swallowers and fire-eaters and painted dancing-girls.

There were cook-shops and toy-booths and merry-go-rounds.

There were itinerant dervish preachers chanting the glories of Allah the One, the Prophet Mohammed and the Forty-Seven True Saints.

There were bear-leaders, ape-leaders, fortune-tellers, bards, buffoons, and Punch-and-Judy shows.

There were large, bell-shaped tents where golden-skinned gypsy girls trilled and quavered melancholy songs to the accompaniment of guitars and tambourines. There was, of course, a great deal of love-making—the love-making of Asia, which is frank and a trifle indelicate.

There were the many street-cries.

“Sugared water! Sugared water here—and sweeten your breath!” would come the call of the lemonade-seller as he clanked his metal cups, while the vendor of parched grain, rattling the wares in his basket, would chime in with: “Pips! O pips! Roasted and ripe and rare! To sharpen your teeth—your stomach—your mind!”

“Trade with me, O Moslems! I am the father and mother of all cut-rates!”

“Look! Look! A handsome fowl from the Khan’s chicken coop!”

“And stolen—most likely!”

Laughter then—swallowed, a moment later, by more and louder cries.

“Out of the way—and say, ‘There is but One God!’”—the long, quivering yell of the water-carrier, lugging the lukewarm fluid in a goat’s-skin bag, immensely heavy, fit burden for a buffalo.

“My supper is in Allah’s hands, O True Believers! My supper is in Allah’s hands! Whatever you give, that will return to you through Allah!”—the whine of a ragged old vagrant whose wallet perhaps contained more provision than the larder of many a respectable housewife.

“The grave is darkness—and good deeds are its lamps!”—the shriek of a blind beggarwoman, rapping two dry sticks together.

“In your protection, O honorable gentleman!”—the hiccoughy moan of a peasant, drunk with hasheesh, whom a constable was dragging by the ear in the direction of the jail, the peasant’s wife trailing on behind with throaty plaints of: “O calamity! O great and stinking shame! O most decidedly not father to our sons!”—her balled fists meanwhile ably assisting the policeman.

There was more laughter; and Fathouma, too, laughed as she followed Hossayn.

Only rarely she left the palace; and everything amused her. She decided she would tell Omar the Black all about it tonight when she saw him—and she progressed slowly through the throng, with the stranger still in back; then she stopped, a little nervous, as there was a brawl between a Persian merchant and a Turkoman nomad who disputed the right of way.

Neither would budge. They glared at one another. Presently they became angry, and anger gave way to rage—and then a stream of abuse, of that vitriolic and picturesque vituperation in which Central Asia excels.

“Owl! Donkey! Jew! Christian! Leper! Seller of pigs’ tripe!” This from the lips of the elderly Persian whose carefully trimmed, snow-white whiskers gave him air aspect of patriarchal Old Testament dignity in ludicrous contrast with the foul invective which he was using. “Uncouth and swinish creature! Eater of filth! Wearer of a verminous turban!”

The reply was prompt: “Basest of hyenas! Goat of a smell most goatish! Now, by my honor, you shall eat stick!”

The stick, swinging by a leather thong from the Turkoman’s wrist, was two pounds of tough blackthorn. It was raised and brought down with full force—the Persian moving away just in time and drawing a curved dagger.

People rushed up, closed in, took sides.

It was the beginning of a full-fledged battle royal—and Fathouma cried:

“Hossayn! Hossayn! Get me out of here!”

But Hossayn was not near her. All she saw of him, some yards away, was his red fez bobbing up and down in the mob, as if he were drowning.

“Hossayn! Oh, Hossayn!”

Farther and farther floated the fez; the mob seemed to be carrying the man away; and Fathouma became terribly frightened—jostled and pushed about—and everywhere the striking fists, the glistening weapons—everywhere the shrieks of rage and pain.

She wept helplessly, hopelessly. Almost she fainted.

Then she felt a firm grip on her elbow; heard a reassuring voice in her ear: “This way, Heaven-born!”

A moment later, a man, tall and broad-shouldered, tucked her under one arm as if she were a child, while with the other, wielding a sword, he carved a path through the crowd. They turned a corner; reached a back alley; his knee pushed open a door; and she found herself in the shed of a provision merchant’s shop.

There, in the dim light that drifted through a window high on the wall, she saw her rescuer: a man with an eagle’s beak of a nose, thin lips, small, greenish eyes. A man—she thought with a start—as like to her husband as peas in a pod, except that his beard was red and not black.…

She knew at once who he was:

“You—you are Omar the Red! Ah, the lucky, lucky day for me!”

“Luckier for myself!”

“My husband will be so grateful.”

“Doubtless. But this time, knowing my brother, I shall make sure, quite sure, of his gratitude.” A smile like milk curdling flitted across his face. “Tell me,” he asked, “how good are you at the riding?”

“The—riding?”

“Yes. On a horse. A horse, swift and powerful, to carry the two of us, and you on the saddle in front of me, and with one of my arms—wah! there have been plenty women in the past who liked the strength of it—around your waist to hold you steady.”

She looked at him.

“Oh,” she faltered, “but—”

“Listen!”

He spoke at length. And, he wondered, was that a laugh trembling on her lips? No, no! it must be the beginning of a cry of fear; and, at once, there was his sword to the fore.

“Be quiet!” he warned her. “Or else—and you the woman and I the tough ruffian—here is the point of my blade for the whitest breast!”

So she was quiet; and he went on:

“Come! My horse is waiting for us—and so are the steppes of High Tartary.”

He led her out of the shed, walking close to her. A loving couple, people would have thought; and none to know that, hidden by the folds of the man’s cloak, a dagger was pressed against the small of the woman’s back.

By this time, the merry-making had ceased. There came the booming of the sunset gun from the great Mosque where, in the west, it raised its minaret of rosy marble. There came, immediately afterwards, the muezzin’s throaty chant that the Night of Honor, the Night of Fear and Repentance, was near; and then lights were extinguished everywhere against the malign flitting of the dark and evil djinns, and the places of worship were filled with the Faithful, the streets and alleys became deserted.

Not a wayfarer anywhere. Hardly a sound.

Only, as a sturdy stallion with two in the saddle rode through the northern gate, a sleepy sentinel’s challenge:

“Who goes there?”

“A merchant and his wife.”

“Travel in peace, O Moslems!”

So Fathouma and Omar the Red were off at a gallop; while at just about the same time, when Omar the Black returned to the palace, there was a Persian lackey telling him a terrible tale—a tale of heroism, showing, in proof, various bruises and even a bandaged shoulder and explaining how he had been attacked by a shoda, a rough customer, had been kicked, cuffed, knocked down, sliced and stabbed with a number of sharp weapons.

With a great throng of men, each intent on his own brawl, all about him, he had been helpless; and—Allah!—the cruel, brutal strength of this red-bearded scoundrel.…

“Eh?” interrupted Omar the Black. “You—you said red-bearded?”

“Superbly, silkily red-bearded. And hook-nosed. And armed to the teeth.…”

“And with an evil glint in his eyes?”

“Most evil!”

* * * *

The Persian went on to relate that here he was, prone on the ground, grievously wounded. And there was the other, with the Heaven-born in a faint and slung across his shoulders as if she were a bag of turnips; and the man’s parting words had been:

“Take a message to Omar the Black. Tell him to come quickly, and alone, and with a queen’s ransom in his breeches. Let him take the Darb-i-Sultani, the King’s Highway, straight north into High Tartary. And, presently, at a place of my own choosing, I shall have word with him.”

Such was the lackey’s story; and Omar the Black did not doubt it, since he knew his brother.

What puzzled him later on—and what, indeed, he cannot understand to this day, though frequently he has asked his wife about it—was what she did or, rather, what she did not do.

Why—he wondered—did she not resist? Why did she neither struggle nor cry out?

“How could I?” she would explain. “At first I thought he had come to rescue me. I was grateful.”

“Still—after you discovered that he…?”

“I was helpless. I am a weak woman—and there was the point of his dagger pressed against my spine.”

“Even so—when you passed, on the saddle in front of him, through the gate—a word to the sentinel…”

“It would have been my last. The dagger…”

“Omar the Red would not have carried out his threat.”

“How was I to know? Such a scoundrel, this brother of yours—you yourself used to tell me—and not at all to be trusted.”

* * * *

So, afterwards, was Fathouma’s explanation; and we repeat that Omar the Black—and small blame to him—was puzzled.

But, at the time of the kidnaping, the only emotion he felt was worry. Dreadful worry. Why, he loved his wife—and ho, life without her, like a house without a light, a tree without a leaf…

As soon as Hossayn told him the news, he took all his money, all his jewels and whatever of Fathouma’s he could find. As an afterthought, he went to the shop of Baruch ben Isaac ben Ezechiel, the rich Jew.

Better too much treasure—he reflected—than too little. He told himself—since, after all, in spite of his worry, he was still the same Omar the Black—that loot was loot and would always come in handy. Therefore, courteously, he asked for credit; was courteously granted it—for was he not the husband of a Tartar Princess and a captain in the Khan’s palace guard?

The merchant salaamed.

“Do not worry about credit, lord. Take whatever you wish.”

Omar wished a lot, took a lot; and, within the hour, followed his wife and his twin brother up the Darb-i-Sultani, into the north.

All night he rode and all the following morning.

At first, near Gulabad, the land was fertile, with tight little villages and checkerboard fields folded compactly into valleys where small rivers ran. But, toward noon, the steppe came to him.

The heart of the steppe.

The heart of High Tartary.

* * * *

IT came with orange and purple and heliotrope; with the sands spawning their monotonous, brittle eternities toward a vague horizon. It came with an insolent, lifeless nakedness; and when, occasionally, there was a sign of life—a vulture poised high on stiff, quivering wings, a jackal loping along like an obscene, gray thought, or a nomad astride his dromedary, his jaws and brows bound up in mummy-fashion against the whirling sand grains, passing with never a word of cheerful greeting—it seemed a rank intrusion, a weak, puerile challenge to the infinite wilderness.

A lonely land.

A harsh and arid land. No silken luxury here. No ease and comfort.

The heat was brutish, brassy. His rheumatic leg ached.

Yet, gradually, he became conscious of a queer elation.

It had been long years—he told himself—since he had left High Tartary. Nor had he ever wished to return. Still—why—it was his own land, his dear land.… “Yes, yes!” he cried; and, almost, he forgot what had taken him here, almost forgot Fathouma. “Here—rain or shine, cloudy sky or brazen sun—is my own land, my dear land! Here is freedom! And here, ever, the stout, happy heart!”

He put spurs to his horse and galloped on, grudging each hour of rest. And afternoon died; and evening brought a gloomy iridescence, a twilight of pastel shades, a distant mountain chain with blues and ochres of every hue gleaming on the slopes; and a few days’ ride beyond the range—he knew—was Nadirabad nestling in the shadows of the old, ancestral castle; and he dismounted and made a small campfire; and night dropped, suddenly, like a shutter, the way it does on the steppe; and out of the night came a mocking call:

“Welcome, brother!”

Omar the Red stepped from behind a rock; and Omar the Black jumped up, sword in hand.

“Dog with a dog’s heart!” he yelled.

“I shall fight you for Fathouma!”

“Fight? No, no! You shall pay me for her—and, by the same token, live up to our agreement.”

So, since curses and threats did not help matters, there was, presently, a deal of money thrown on the ground and a wealth of glittering jewels—some come by honestly, and some less so.

“Enough,” remarked Omar the Red “to pay back the debts to the Nadirabad merchants—and to lift the mortgage on the castle—and for Ayesha and me to live on comfortably for a number of years.”

“For more than a number of years,” announced Fathouma, stepping into the flickering light of the campfire. “Indeed until the end of your days—if you are ready to do your share of proper toil.”

She turned to her husband.

“The soil up yonder, your brother tells me, is fat,” she continued, “and the grass is green and sappy and the water pure. A fine chance, in your own country, for a man’s hard, decent work—even a man of your years—and there we shall live, the four of us, and thrive—God willing!”

“You,” stammered Omar the Black “you said—the four of us?”

“Ayesha and your brother—and you and I. Can you not add two and two?”

Now this—to live once more at home—had been the very thing which, deep in his soul, he had dreamed of and longed for, ever since he had come to the steppe. But it would not do for a man to give in too quickly to his wife.

“Nothing of the sort!” he replied. “We shall ride back to Gulabad and—”

“Listen!” she interrupted.

“Yes?”

She stepped up close to him.

“Would you want,” she demanded, lowering her voice, “your child to be born in an alien land?”

He gave a start.

“My—my child?”

“Mine too.” She smiled. “Our child, before the end of many months. Oh yes—my hair is gray. But,”—blushing a little—“I am not as old as all that.”

Then he took her tenderly into his arms. “By the Prophet the Adored!” he cried triumphantly. “Let it be a man-child, a little son, to you and me! A strong little son! The strongest in all High Tartary—”

“Except,” cut in Omar the Red, “for the son whom Ayesha shall bear to me.”

“Liar!”

“Liar yourself!”

“Drunkard!”

“Unclean pimple!”

Almost, they came to blows.

* * * *

AND the end of the tale?

The end of the tale is not yet.

But, up there in the ancient castle in High Tartary, live two white-haired men. White-haired, too, their wives. And the latter exchanging winks when, occasionally, their husbands comment naggingly, querulously, about the morals of Islam’s younger generation, including their grandsons.…