Читать книгу Flemington And Tales From Angus - Violet Jacob - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

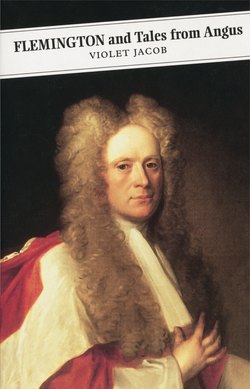

Annie Cargill

ОглавлениеYOUNG BOB Davidson had an odd assortment of tastes. He combined the average out-of-door sporting tendencies with a curious love of straying down intellectual byways. He was not clever and he had been very idle at school; he knew no Greek, had forgotten such Latin as had been hammered into him, was innocent of modern languages, and abhorred mathematics. The more amusing passages of history gave him true pleasure and heraldry was a thing that he really knew something about. He was twenty, and in mortal combat with his father over the choice of a profession. Old Mr. Davidson favoured the law and his son’s mind was for a land agency. In the midst of the strife Bob’s godfather, Colonel Alexander Lindsay of Pitriven, invited him to spend a fortnight with him and to shoot the dregs of the Pitriven coverts. Bob hesitated, for he had never seen Sandy Lindsay and had at that moment some private interests in Edinburgh; but Mr. Davidson, a Writer to the Signet, had no idea of offending a godfather who was also a well-to-do bachelor. So Bob, grumbling, packed his portmanteau and a copy of Douglas Whittingham’s Armorial Bearings of the Lowland Families and departed for Pitriven. The young lady who represented the private interests cried a little and desired the housemaid to abstract her early letters, daily, from the hall table.

Pitriven was a small, shabby house with an unlived-in atmosphere that laid hold upon the young man as he entered; a long-disused billiard-table almost choked the hall, and only the comforting smell of tobacco cheered him as the butler led him into his godfather’s presence. At any rate, he reflected, he would be allowed to smoke. Somehow, the place had suggested restrictions.

‘Sandy Lindsay,’ as he was always called, astonished Bob more than anyone he had seen for some time. He was so immensely tall that his head nearly touched the ceiling of the low smoking-room, and in the dusk of the December afternoon his gigantic outline practically blocked up the window in front of which he stood. He had stiff, white whiskers which curled inwards; his brassy voice had the harshness of a blow as it broke the silence. His features were not ill-favoured, but they looked as though carved out of wood with a blunt knife. Bob found him civil, almost cordial, but there was a hint of potential roughness lurking behind voice, words and manner that had a disturbing effect and gave the young man the sensation of knowing neither what to speak of, nor what to do, nor what to think.

But by the time he had been a few days at Pitriven Bob had begun to like Sandy Lindsay, though he would wonder sometimes, as they sat at the hearth in the evening, what quality in the man beside him had attracted the friendship of his father. He could not quite get over his first impressions but he told himself that it was childish to blame his godfather for having a dreadful personality; he had not chosen it for himself. But it was quite clear to Bob that it was a dreadful one. He found himself noting with surprise that Lindsay’s dog was not afraid of him. Somehow he had taken it for granted that the red setter which lived in the house and slept at night in the smoking-room would feel what he felt, perhaps more strongly.

He could not fathom his godfather. There was a rude detachment about him that he could not penetrate; he was alien, out-of-date, barbarous. He decided that he was ‘a survival,’ for he was fond of making definitions in his careless way, and so he put it. He looked him up in a Landed Gentry that he found lying about and was mightily astonished to see that he was seventy-one. Certainly he did not look it.

Though Pitriven house had little attraction for Bob, its surroundings held much that he liked. The timber was beautiful and the great limbs of the trees, with their spreading network of branches etched upon the winter skies, dwarfed the mansion and gave it an insignificance that had something mean. The windows were like malignant eyes staring out into the grandeur of trunk and bough.

The parks round Pitriven were cut by a deep ‘den’ beyond which the ground rose, steeply, to old Pitriven Kirk. Trees choked the cleft and clothed the ground about the building, but now that the leaves were fallen its walls could be seen from the windows of the house, perched above the den and rising from among the gravestones. Bob had passed near it when shooting with his godfather; his eye had fallen upon the armorial bearings which decorated much of the older stonework, and he promised himself a good time spent in the researches dear to his heraldic soul.

One afternoon he set forth with his notebook in his pocket and a veteran scrubbing-brush in his hand that he had begged from the housemaid; for he had seen that the mosses were thick upon the gravestones. When he went in at the kirkyard gates he stood a while looking round upon the place and contrasting the semi-modern stones with the ancient table-topped ones set thick in that corner of the enclosure where the older graves clustered by the low boundary wall. The kirk was in ruins and stood, like a derelict among the masts of a harbour, in the midst of the upright stones; for the modern kirk which sheltered the devotions of Pitriven parish was some little way off. Bob Davidson, considering the prospect and listening to the soft rush of water in the den below, took in the expression of the place with an interested eye. It was so near to humanity, yet so remote. The kitchen-garden wall flanked it on one side, but its air of desertion and finality set it miles away, in spirit, from living things. The afternoon was heavy and thick, like many another near the year’s end. It was as though nature, wearied out, could struggle no more and was letting time run by without the effort to live.

He was not long in choosing a table-topped monument whose square mass had sunk from its proper level, and he set to with his scrubbing-brush upon the layer of moss which, to judge from a piece of mantling that stuck through its green woof, must hide some elaborate design. He foresaw a long task, for the growth was not of that spongy sort which can be ripped back like a carpet, but a close and detestable conglomeration of pincushion-like stuff that defied the power of bristles. He fell to with a blunt stick and worked on and on until his back ached, and he straightened himself, stretching his arms. His eyes were tired and he had bent forward so long that he was quite giddy. He sat down on the stone and looked round again.

The place had been closed for burials for about thirty years and there were no distressingly new monstrosities to spoil its quiet effect. Opposite, on the farther side of the kirk, the local dead of the last half-century were gathered together, herded in a flock according to their generations as they had been herded whilst living. Where Bob sat, the environment was historic, but yonder it was merely dull.

His eye lingered upon the most prominent of those gathered graves, or rather upon its appurtenances, for the headstone was invisible, being surrounded by a rusty iron railing made of chains that hung in a double row, festooned between the uprights. Inside the enclosure there stood up such a nest of Irish yews that nothing could be seen but their close blackness; some leaned on their neighbours, thrust sideways by the east-coast wind, but all were cheek by jowl, a conspiracy of heavy shadows in the dull light of the pulseless afternoon.

Bob disliked their look, suddenly, and for no reason; they were too much dilapidated to be imposing, and the stone which, presumably, they sheltered could not have the dignity of the one on which he was working, for the battered chains of the railing made a futile attempt at pomp that went ill with everything near it. Yet the atmosphere hanging about that enclosed place was not commonplace; it had some other and worse quality. A wave of repulsion, half spiritual, half physical, came over him, so that he was near to shuddering and he turned to go on with his cleaning; at least the scrubbing-brush was prosaic and therefore comfortable.

While he worked he found that a small, fresh-faced, rather sly-looking old man with a rake over his shoulder was contemplating him from the other side of the low wall. He was smiling too, with a slightly interested and wholly curious smile that uncovered four teeth divided by enormous gaps.

‘Guid wurk,’ said he, with the amused patronage that he might have given to a child at play.

‘It’s harder than you think,’ said Bob.

The old man clambered over the wall with deliberation, his heavy boots knocking against it, and stood by Bob. The brush had uncovered a coat of arms, several skulls and crossbones and a long Latin inscription.

‘Yon’s dandy,’ observed the new-comer, looking at him with approval, as though he were responsible for the whole.

‘It’s a pity they’re so smothered up in moss,’ said Bob. ‘I’ve no doubt there are plenty better than this one.’

But the other was more interested in Bob than in antiquities.

‘Ye’ll be a scholar?’ he inquired, with the same suggestion of suppressed comedy.

‘Well – no; but I like these things.’

The old man laughed soundlessly.

‘Graves doesna pleasure mony fowk owre muckle,’ said he.

‘There’s one over there that doesn’t pleasure me very much,’ returned Bob, pointing to the huddled company of Irish yews.

His friend’s eye followed the direction of his finger; then his smile widened and his eyebrows went up. He seemed to take a persistently but sardonically jocose view of everything in this world.

‘Yon?’ said he, wagging his head, ‘fegs, there’s them that’ll agree fine wi’ ye there!’

‘Why, what do you think of it?’ asked Bob.

‘Heuch! what wad a’ be thinkin’?’ exclaimed the other, putting his rake over his shoulder again; ‘a’m just thinkin’ it’s fell near time a’ was awa’ hame.’

He moved away with a nod which conveyed to Bob that he still took him for a semi-comic character.

‘But who’s buried there?’ cried the latter after him.

‘Just a lassie!’ called the old man as he went.

When he had disappeared Bob went over to the yews. He would have laughed at the idea of being nervous, but there was that in him which made him keep his eye steadily on the enclosure as he approached it. He found that it was not, as he imagined, quite surrounded by trees, for the foot of the grave was clear and from it he could see into the darkness to where the plain, square stone sat, as though in hiding, like the inmate of a cave. He stepped over the chains and stood above the ‘lassie’ to read her name. There was no date, no text, not the baldest, barest record; only ‘ANNIE CARGILL.’

The name lingered in his brain as he went home. It conveyed nothing, but he could not get it out of his head all that evening. The odd feeling that the surroundings of these two carved words had given him stamped them into his mind. Once or twice, as he sat after dinner with Sandy Lindsay and the red setter, he had almost opened his mouth to ask some question about them, but he did not do so. His godfather was the last man to whom he could speak of anything not perfectly obvious, and he guessed that he would not only think him a fool for the way in which he had spent his afternoon but call him one too. Bob always steered clear of conversational cross currents. It was one of the reasons that he was genuinely popular.

He did not go back to the kirkyard for several days, but when the next opportunity came he departed secretly, for Sandy Lindsay had gone to a sale of cattle and the coast was clear for him to do as he would. He had come to accept his godfather’s disapproval of these excursions of his as certain – why he could not tell. Also, he hoped he should not meet the old man with the rake, for the subtle mixture of reticence and derisive patronage with which he had been treated did not promise much. He was beginning to be glad that he was leaving Pitriven in a few days, for he was a little tired of being out of real sympathy with anybody and he had not exchanged a word with a creature of his own age since he left Edinburgh.

‘I am pleased that you have managed to get on well with Lindsay,’ his father had written. ‘He is an odd being and I can understand something of your surprise at our friendship. As a matter of fact, I have seen very little of him for a number of years, but your mother’s people were under some obligation to him and she never forgot it, and since her death I have not let him quite slip out of my life. There were strange stories about him in his youth, I believe, but they were none of my business, nor did I ever hear what they were…’

His father’s want of curiosity was tiresome, Bob thought.

He hurried along, for he needed all the light he could get and he had started later than he intended. There were two stones close to the first one which he wanted to uncover and he stuck manfully to them till both were laid bare. He was interrupted by nobody, but when at last he took out his notebook to make a rough sketch of the complicated armorial bearings which made one of them a treasure, the light was beginning to fail. He scrawled and scribbled, then shut up the book with a sigh of relief. His fingers were chilly and he could hear the wheels of Lindsay’s dog-cart grinding up the avenue on the further side of the den. He would have one more look at Annie Cargill, and go. He had almost forgotten her sinister fascination as he worked.

As he approached across the grass a small bird skimmed swiftly out of a tree, as though to light in one of the Irish yews, but turned within a yard of its goal, with a violent flutter of wings, and flew almost into Bob’s face. Another step took him to the foot of the grave, and there he stepped back as though he had been struck.

A figure was sitting crouched in the very middle of the dank closeness inside the chains, and he knew that it was this that had made the bird change its course. He would have liked to do the same but he stood there petrified, his heart smiting against his ribs and a cold horror settling about him. He could not move for the swift dread that took him lest he should see the creature’s face; he could not make out whether the huddled shape was male or female, for the head was averted and it seemed to him in this desperate moment that, if it turned, his eyes would meet something so horrible that he could never get over it, never be the same again. He felt the drops break out under his hair as he stood, not daring to move for his insane fear of attracting attention.

The dusk was not far advanced, but between the closed-in walls of the yews the outline of the figure was indefinite, muffled in some wrapping drawn about its head and shoulders. It might be an old woman – he thought it was – it might be a mere huddled lump of clothes, though why they should be in that place was beyond his struggling wits to imagine. He tried to take his eyes from the thing – for it had no other name to him – and as he did so, the head turned as quietly and as independently of the rest of the body as the head of an owl turns when some intruder peers into the hollow in which it is lodged. The young man saw a wisp of long hair and a mouth and chin; the upper part of the face was covered by the hood or cloak, or whatsoever garment was held close about the bodily part of the lurking presence between the yews. It was a woman.

The discovery of something tangible, something definite, brought back a little of his banished courage and gave power to his limbs. He walked away swiftly, his face set resolutely to the kirkyard gates, not looking behind. As he trod on a stick that cracked under his boot he nearly leaped into the air, but he went on, stiff and holding himself rigidly together. His notebook and scrubbing-brush lay on the table-topped stone; he had forgotten them, nor, had he remembered them, would he have gone back to fetch them for all the kingdoms of the world.

He hurried out of the kirkyard and through the door of the walled kitchen garden. His heart was beating and the sight of a gardener, a healthy-looking, upstanding young man who was coming out of a tool-shed, was of infinite comfort to him. Here was a human being, young and stirring like himself, a normal creature, and his presence brought him back into the everyday, reasonable world which had receded from him in the last few minutes. As they passed each other he stopped.

‘I say,’ he began.

The other touched his cap.

‘Look here,’ said Bob, rather breathlessly, ‘there’s something so odd in the kirkyard – there!’

He threw out his arm towards the place where the gable of the ruin showed above the garden wall.

The gardener stared at him, astonished.

‘What like is it?’ he asked, setting down the basket he carried.

‘It’s – a person,’ said Bob.

Visions of accidents, poachers, trespassers, swept across the gardener’s practical mind. He moved forward quickly, and a chill ran over Bob again at the thought of going back into the kirkyard. But the human personality beside him put a different aspect on everything and he was immediately ashamed of his childishness.

They went out of the garden together and made their way among the stones to Annie Cargill’s grave. At the head they paused and Bob went softly round the trees to the gap at its foot, the other following; and here he stopped in blank astonishment.

The place was empty

He turned to the gardener, speechless, feeling like a fool.

‘It’s gone!’ he exclaimed at last.

The other pushed back his cap and stood looking at him with a half smile.

‘I suppose you think I’m mad,’ said Bob, throwing out his hands, ‘but I tell you it was there – not a minute ago – just before I met you!’

‘But wha was it?’ said the gardener.

‘That’s what I want to know!’ cried Bob. ‘It was a woman – an old, old woman – I am certain it was a woman. It was there, sitting huddled up in front of the stone.’

‘There’s no auld body comes in hereabouts that a can mind of.’

‘It looked mad – extraordinary,’ continued Bob, ‘not like anyone I’ve ever seen.’

‘Well, it’s awa now, anyhow,’ said the gardener.

‘But who was Annie Cargill?’ burst out Bob. ‘There’s something strange about this place – I know there is! An old man I met here told me so – but I knew it myself. He said other people besides me don’t like the look of those trees and that chained-in place. He couldn’t have been lying – why should he tell me that?’

His companion seemed as non-communicative as the man with the rake, but Bob felt that he would be put off no longer. It was too annoying; also he had a passionate desire to justify himself, to force some admission that he was not altogether childish in his excitement.

‘Well, maybe a’ve heard tell o’ things,’ said the other cautiously; ‘a’ll not say that a havena’. But a’ve been here just twa year – it’s fowk aulder nor me that ye should speir at.’

‘But who was Annie Cargill?’ cried Bob again. ‘That’s what I want to know! The old man said she was “a lassie”.’

‘She was a lassie, and she wasna very weel used, they say. There was them that made owre muckle o’ her, that set her up aboon her place. She was just a gipsy lassie.’

‘A gipsy?’

‘Well, a dinna ken the rights o’t, but they say she was left to dee her lane, some way aboot the loan yonder.’

‘And who left her to die?’

A look came over the gardener’s face that made Bob think of the closing of a door.

‘A canna just mind about that,’ he replied. ‘A ken nae mair nor what a’m telling ye. An’ they buried her in here.’

‘Was she pretty?’ asked Bob.

‘Aye was she,’ said the other. ‘But she’ll no be bonnie now,’ he added grimly. ‘She’s been lyin’ here owre lang.’

‘And the trees? Who planted the trees?’

‘Well, they were plantit to hide the stane,’ said the gardener. ‘It’s an ugly thing and ye can see it frae the windows o’ the house.’

‘But they don’t hide it,’ rejoined Bob; ‘you can see it quite well, even across the den.’

‘Aye, but there’s twa trees wantin’ at the fit o’t. They were plantit, but the wind wadna let them stand. They got them in three times, they say, but the wind was aye owre muckle for them.’

‘There’s no mark of them now.’

‘Na. They wadna stand, ye see, and the roots was howkit out. It’s forty year syne that they did that.’

‘Well, it’s an extraordinary place,’ said Bob, as they turned to go, ‘and it’s a more extraordinary creature that I saw in there. Come outside and let us look if we can find any trace of her.’

They walked through the wood, then ran down to the den, they searched about in the neighbouring byroad and in the fields. No one was to be seen and the gathering dusk soon sent the gardener to lock the garden doors. He was anxious to get back to his tea. Bob bade him good night and they parted.

When the dinner-bell brought Bob downstairs that evening, Lyall, the butler, was waiting for him in the hall. He was to dine alone, it seemed, for his godfather was not going to leave his room. He had got a chill at the cattle-fair, said the butler, for he had refused to take his greatcoat with him, although it had been put in the dogcart. He had thrown it out angrily – so Bob gathered – and the butler had been angry too. He was grim to-night and wore the tense and self-righteous face of one who is justified of his words. Bob ate in silence and then betook himself to the smoking-room with the setter and installed himself with a book.

It was ten o’clock when Lyall came in and asked him to go up to Lindsay’s room; he had been having great trouble with his master, and, though from the old servant’s customary manner Bob believed himself to hold a mean place in his estimation, it was evident that he wished for his support now.

‘Hadn’t you better send for the doctor?’ he asked as they went out together.

The other snorted.

‘A doctor?’ he exclaimed. ‘I’ve done my best, but it’s neither you nor me that can make him see a doctor! There’s no doctor been in this house since I cam’ to it, and that’s twenty-five years syne.’

Lindsay was lying in his solid fourposter with his angry eyes fixed on the door; he looked desperately ill and as Bob approached he sat up.

‘What are you doing here?’ he cried. ‘Who told you to come up?’

The butler went quietly out. He had no mind for another scene.

‘I came to see how you were, sir,’ said Bob. ‘I am sorry you are not well.’

‘Now look here!’ said Lindsay, ‘let me have none of your nonsense here. That damned old fool outside has been telling me I ought to send for a doctor. I’ll have none of that! If you have come to say the same thing, out you go, and be quick about it too. I’ll see no doctors, I tell you! I’m not going to have one near me. I hate the whole lot! A set of…’

His abuse was searching. He shouted so loudly that the dog below in the smoking-room began to bark.

‘I’m not going to ask you to do anything,’ said Bob quietly, ‘only I wish you would lie down and get some sleep. I can sit here and if you want anything I can get it for you. Then you need not have Lyall up here to bother you.’

Lindsay looked at him suspiciously but he seemed not ill-pleased. He lay down again and turned over with his back to the young man.

The shutters were not closed nor the blinds pulled down and Bob was afraid of rousing Lindsay by moving about, so he sat quite still till the breathing in the bed told him that his godfather was asleep. The hands of the clock ticking on the mantelpiece were hard on eleven when he rose and went downstairs, priding himself a little on the success of his methods. He had just time to find his place in his book when a violent bell-ringing woke the house.

He heard Lyall run upstairs and he sat still, waiting. In another moment the man was down again.

‘You’ll need to go back, sir,’ said he. ‘The Colonel wants ye.’

Bob ran up.

‘Why did you go?’ cried Lindsay. ‘Stay here. You said you would stay! That damned fellow, Lyall, will drive me mad with his doctors. Don’t let him in!’

Bob looked at the harsh face and white whiskers of the solitary, uncouth old man in the bed. He pitied him, not so much because he was ill, but because of his rough, forlorn detachment from the humanities.

‘It’s late, you know, sir,’ said he, ‘but I’ll get my mattress and sleep on the floor. I will stay, certainly.’

The idea seemed to quiet Lindsay and he fell asleep; now and then he tossed his heavy body from one side to another, but Bob made up his shakedown bed and got into it without interruption and was soon lost in the healthy slumber of youth. He was roused from it a short time later by something which was not a noise but which had made appeal to some suspended sense of his own. He sat up.

There was no moon, but the starless night had not the solidity of deep darkness. The unshuttered window gave him his bearings when he looked round wondering, as the sleeper in a strange bed so often wonders, where he could possibly be, though its grey square was almost blocked out by a figure before it. Lindsay had got out of bed and was standing, just as he stood when his godson first entered Pitriven, colossal and still, against the pane.

Bob struck a match quickly and Lindsay turned as the candle-flame rose up.

‘Put it out!’ he said fiercely. ‘I tell you, put it out! Do you want the whole parish to see in?’

‘Come back,’ begged Bob, ‘for heaven’s sake go back into your bed – why, you will perish with cold standing there.’

He was on his feet and half-way to the window.

‘Do you hear me?’ roared Lindsay. ‘Put out that damned candle!’

Bob obeyed and then went and laid his hand on Lindsay’s sleeve. Though the old man was not cold his teeth were chattering.

He shook him off.

‘Look at that,’ he said, pointing into the night outside.

‘Go to bed, sir – please go to bed,’ said Bob again.

‘But look!’ cried Lindsay, taking him by the shoulder.

The young man strained his eyes. The windows looked straight across the cleft of the den towards the spot where the kirk stood high upon the farther bank. The indication of a dark mass was just visible, like a pyramid thrusting into the sky, which Bob knew must be the crowded yews round Annie Cargill’s grave.

‘Do you see the light?’ asked Lindsay.

‘Where?’ said Bob, peering out, ‘I can’t see anything.’

‘Are you blind, boy?’ cried Lindsay – ‘it’s there by the foot of the trees, and she’s there too! She’s old now – old – old. Not like she was then!’

Bob turned colder. The young gardener’s words came back to him. ‘She’s no bonnie noo,’ he had said, ‘she’s been lyin’ there owre lang.’ It had seemed to him a grim speech, but its suggestion then had been of mere physical horror. His godfather’s words conveyed a spiritual one.

‘By the trees,’ he said. ‘Which trees?’

‘Good God, can’t you see it, you young fool?

There’s a little dim light – at the foot – in the gap.’

Bob was silent. He knew exactly which place Lindsay meant.

‘It’s there!’ cried the other again – ‘beside her – round her!’

He seemed to be terribly excited, and Bob, who felt the burning fever of the hand gripping his shoulder, longed to get him back between his sheets. He was quite certain that he was delirious.

‘Yes, I see it now,’ he said, lying, but hoping to quiet him, ‘perhaps it is a bit of glass or a shining stone.’

He knew how senseless his words were, but they were the first that came into his head.

‘The stone’s in there,’ said Lindsay, ‘in among the trees. But they won’t hide it – they won’t hide her!’

‘I know,’ said Bob; ‘come, sir, you must rest.’

‘Rest? I can’t rest. She knows that. She has known it for years. Ah, she’s old now, you see, and bitter. Older – every year older—’

Bob tried to draw him away. To his surprise the other made no resistance. Lindsay lay down and he covered him carefully. He put on a coat that was hanging in the room and sat down by the bed; he wondered dismally if this miserable night would ever end. It was past one o’clock and he resolved that he would send for a doctor the moment the house was stirring. He dared not leave Lindsay and he dared not ring the bell for Lyall, lest he should upset him further. In about half an hour he rose and crept into his shakedown to sleep, for the old man was quiet.

All the rest of his days Bob wondered what would have happened if he had kept awake. How far might he have seen into the mysteries of those fringes of spiritual life that surround humanity, and how far listened to the echoes that come floating in broken notes from the hidden conflict of good and evil?

A faint light was breaking outside when consciousness came to him with the knowledge that he was half frozen. His limbs were aching from the way in which he had huddled himself together. A strong draught was sweeping into the room and when he lit the candle he found that the door was wide open. He leaped up and shut it, and then went softly to see whether Lindsay slept.

The bedclothes were thrown back and the bed was empty.

He dressed hurriedly and ran out into the passage. Lindsay’s clothes, which had been lying on a chair at the foot of the fourposter, had disappeared with their owner. When he reached the hall the air blew strong against his face, for the front door stood wide and a chill wind that was rising with morning was heaving the boughs outside. No wonder that he had shivered on the floor. On the inner side of the smoking-room door the setter was whining and snuffling. He turned the handle and looked in, vainly hoping that he might find Lindsay, and the dog rushed out past him, through the house door and into the December morning, with his nose on the ground. He watched him as he shot away towards the den of Pitriven, and followed, running.

A wooden gate led to the bridge that spanned the den, and here the setter paused, crying, till Bob came up with him. As the gate swung behind them the dog rushed on before, up the flight of steps that ascended to the kitchen garden.

Bob knew quite well where he and his dumb comrade were going, and his heart sank with each step that took them nearer to their goal. But he was a courageous youth, in spite of his spiritual misgivings, and it would have been impossible to him to leave anyone in the lurch. Nevertheless, he remembered, with instinctive thankfulness, that the outer door of the garden would be locked and that he must rouse the gardener in the bothy if he wished to get through it.

The bothy was built against the outer side of the wall, but one of its windows looked in over the beds and raspberry canes. He took a handful of earth and flung it against the pane. The window was thrown up and the face of the young man he had met that afternoon looked out, dim in the widening daylight.

‘It’s Colonel Lindsay!’ shouted Bob, ‘he is ill – he is somewhere there! Come down quick for God’s sake, and bring the key of the door, for we must find him!’

He pointed to the kirkyard, and as he did so he noticed that the dog had not followed him across the garden. He could hear him barking among the gravestones. As he waited for the gardener, Bob remembered, what he had forgotten before, that there was a short cut to the place through a thicket. The trail the setter followed must have turned off there.

The head above disappeared. The gardener was half dressed, for he was rising to go to his hothouse fires. He was inclined to think that Bob Davidson was wrong in the head, but he came down with the key in his hand.

They took the same way that they had taken in the afternoon, and passed through the kirkyard gate into a world of shadows and stones. The great black mass above Annie Cargill’s head was a landmark in the indefinite greys.

The two young men approached and it seemed to them as though a swift movement ran through the yew trees, as though something they could not define stirred amongst them. They advanced, heartened each by the other’s presence, and paused where they had stood in the falling light of the winter evening. Sandy Lindsay was lying dead on Annie Cargill’s grave.

* * *

A FEW MINUTES later they went to fetch a hurdle on which to carry him to the house. Neither was anxious to remain alone till the other returned, so they went side by side. Bob was asking himself, what was that light, invisible to his own eyes, which Lindsay had seen? God only knew; he could not tell.

The setter stayed behind, but not to watch by his master’s body, after the traditional habit of dogs. He crouched by the gap made by the missing trees, staring into the gloom of the enclosure, his feet planted stiffly before him – snarling at something to which the two young men had been blind, but which was evidently plain to him.