Читать книгу Bosch - Virginia Pitts Rembert - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

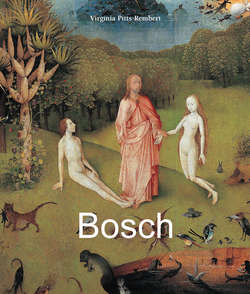

Introduction

Оглавление7. Illuminated manuscript from the 15th century (c.1470–1480), Flanders (Bruges). National Library of Russia, Saint Petersburg

A 17th-century English ambassador to Holland expounded on the virtue of painting over sculpture, by saying: “An excellent piece of painting is, to my judgment, the more admirable object because it is a near Artificiall Miracle.” (Fuchs, 103) The historian who quoted this statement repeated the term “Artificiall Miracle” several times to refer to the Dutch penchant for “the meticulous rendering of things observed.”

The term could also accommodate the whole spectrum of Dutch art from Jan van Eyck to Jan Dibbets for its relevance to the astringent yet probing combination of subject and essence that is peculiarly Dutch. In this sense, the term might even apply to such seemingly disparate artists as Hieronymus Bosch and Piet Mondrian. One artist made real the unreal and the other made unreal the real, but they pursued their uncommon aims through lovingly treated surfaces that survived them as “Artificiall Miracle[s].”

I think Bosch and Mondrian were linked in other important ways. As Nordic artists, they belonged to a group that “has never been content with the mere reproduction of an object,” as art historian Oskar Hagen put it: “There must always be a concomitant vibration in the picture of something spiritual, something indefinable, divinable… it had to be capable of giving simultaneously a real and an unreal, a corporeal and a spiritual picture of things…”)

Both of these artists lived in a century of millennial consciousness and both responded to this consciousness in their work. A case could be made that Mondrian was a millennial artist of our era. At a great distance from Bosch in time, circumstance, and ideology, Mondrian presented a vision of what the modern world could be, if we looked toward harmony rather than tragedy, which he saw not only in war but in cultural manifestations that had become mired in particulars rather than essentials. In his years spent in Paris and London between the twentieth century’s two world wars, Piet Mondrian invented a painting that did not transcribe existing reality, but “imaginatively constructed” what he called a “new reality.” (Mondrian, Plastic, 10) Through its containment, purity, and harmonious ordering of parts, Mondrian posited his painting as an aesthetic cosmos, the “clear vision” of the “pure reality” he hoped would come to pass in the ideal world of the future.

Obviously, Mondrian’s 20th-century creations are divided by radically different sensibilities from those of Bosch’s, at the end of the Middle Ages-or did the two artists reveal the dark and light sides of human coinage? Perhaps, Mondrian’s paintings show what we could become, if we lived in harmony with the universe, or Bosch’s what we would become if we did not heed the Judgement, as seen through two millennial perspectives, five centuries apart.

* * *

After turning to Dutch art, in general, Bosch’s background, and his treatment in literature until the twentieth-century, I shall concentrate on one of Bosch’s paintings, the Lisbon “Temptation of Saint Anthony,” because it was probably completed right around 1500, the half-millennial time fraught with the fears and uncertainties that such a transitional period brings. I developed an interest in the Saint Anthony theme by seeing an exhibition of modern paintings on this subject in New York City, in 1946.

These had been commissioned from about a dozen of the major Surrealist artists by the producers of a motion picture that was to be based on a story by Guy de Maupassant. Although the story, entitled The Lives and Loves of Bel Ami, pivoted around a painting whose religious power had converted a debauched man, the producers had decided to change the subject of Christ walking on the waters, prohibited by the Hollywood Censorship Office at that time, to Saint Anthony’s temptations by the Devil.

A painting by Max Ernst was chosen as the most provocative treatment and as best suited for inclusion in the movie. This being the time of bare transition from black and white to color, the Ernst painting was the only thing shown in the film in color, giving it a powerful impact. (I later saw Ernst’s painting and the others, each fascinating, brought together in an exhibition called “Westkunst,” in the summer of 1981, in Cologne, Germany. I shall use reproductions of some of these paintings in the text.)

The subject of Saint Anthony and his temptations has been of interest to artists through the centuries, in a range from fifteenth-century woodcutters to Cézanne. It was bound to be a favorite for Bosch, who turned to this theme in at least a dozen paintings and drawings; some of these will be incuded in the text.

To reveal the richness of the theme through Bosch’s work was reason enough for me to produce one more book on Hieronymus Bosch. Another reason, equally compelling, was the apparent reappearance of many of the beliefs current in that artist’s time as we mounted the transition from the Second Millennium to the Third. I hope that the following account will afford some interest and insights, even for the many current scholars of Bosch.

8. Armorial of the Confraternity of Our Lady, detail, blank blazon of “Hieronymus Aquens alias Bosch”, Bois-le-Duc, Illustre-Lieve-Vrouwebroederschap