Читать книгу Pretty Things - Виржини Депант - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHÂTEAU ROUGE. A TERRACE, ON A SIDEWALK, IN the middle of construction. They’re seated side by side. Claudine is blond, in a short pink dress that seems sensible but leaves some of her chest visible, the perfect doll, meticulously put together. Even her way of slouching, elbows on the table, legs spread out, has something refined about it. Nicolas’s eyes are very blue, he always looks like he’s laughing, about to do something mischievous.

He says, “Fuck it’s nice out.”

“Yeah, it hurts your eyes.”

She forgot her sunglasses at home, she creases her forehead and adds, “I feel weird, seriously. Like right now, it’s burning.” She touches her throat and swallows.

Indulging her, Nicolas shrugs his shoulders slightly. “If you didn’t pop antidepressants like they were candy, you’d probably feel better.”

She breathes a long sigh, raises her eyebrows.

“I don’t feel like you’re being very supportive.”

“Likewise. You could even say I feel more fucked now that I know you.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

He’s tempted to get angry, point out that she isn’t funny, but it stays lodged in his throat and he settles for smiling. The waiter arrives, flings down two coasters and two half-pints on top of them. Impeccable moves. The bubbles rise through the gold in straight, rapid lines. They clink glasses mechanically, exchanging a brief glance. At the next table, a kid makes noise slurping the bottom of his grenadine with a straw.

Nicolas stubs out his unfinished cigarette, really flattens it to make sure it goes out, and declares, “It’ll never work. It’s impossible to mix you two up.”

“Good one, sweetheart, we’re only twin sisters.”

“So how do you explain that I didn’t even recognize her when I went to get her at the train station?”

Claudine pouts comically, revealing she doesn’t get it either.

Nicolas insists, “She passed right under my nose, I didn’t raise an eyebrow when I saw her. It wasn’t until all the passengers cleared out and we found ourselves alone, side by side, that I saw a vague resemblance between you and her.”

“Maybe you’re kind of an idiot. Have to take that into account.”

The waiter passes by their table, Nicolas signals for him to bring two more of the same. Then, rubbing his forehead with two fingers, looks into the distance as if he were contemplating the issue. When he’s had enough of not talking, he goes off again.

“She’s nuts, your sister, totally insane.”

“She’s just grunge. Compared to the freaks Paris churns out, I find her pretty calm.”

“There’s no denying it. In the course of an afternoon, I heard her say exactly four words, and they were ‘You can fuck off.’ You call that calm?”

“Put yourself in her shoes, she’s on the defensive.”

“What bothers me is that you didn’t even warn me. You forgot to tell me lots of things, I’m sure.”

She tenses, turns her head toward him, and he knows this face, when she loses her composure and becomes downright nasty.

“Do you plan on being a pain in the ass all day? If it bothers you, then by all means, don’t force yourself. Go home, don’t worry about a thing. We’ll make do without you.”

She doesn’t leave him time to respond, gets up and goes to the bathroom. The lock is all rusted and falling to pieces, yellow traces of cigarettes like scars on the toilet paper roll. Squat toilet, be careful not to spray your feet too much when you flush.

Chest struck with a strange heaviness, she wants to be somewhere else. Rid of herself. That horrible anxiety is ingrained, it wakes up at the same time as her and doesn’t let up until she’s had a few beers.

She sits back down next to Nicolas. A girl passes by in a combination of snakeskin and bizarre platform shoes. Farther off, a man yells, “Stop, thief!” Some people run and others get involved. Elsewhere, a honk, like a foghorn, as if an ocean liner were docking in the neighborhood.

Claudine rummages in her bag, takes out her cash and spreads it on the table, announcing, “No tips for assholes, that guy pisses me off.”

“The waiter? What’d he do to you?”

“He doesn’t even try. He sucks.”

She pockets the pack of cigarettes and the lighter, concludes dryly, “So will you go with her or not?”

“I told you I’d do it, so I’ll do it.”

“Great. Let’s go?”

She has a slightly satisfied glimmer in her eye. She gets up and waits for him, then in a relieved tone, “I love it when it starts to get hot out, don’t you?”

Nicolas and Claudine have known each other for a while now.

The day she came to live in Paris. She remembers like it was yesterday. Decision made without any planning, she was talking to a girl on the phone, listed off their friends to bitch about them. She heard herself say, “Anyway, I’m taking off, I’m going to Paris, I don’t want this life anymore, where tomorrow never means anything.” And, hanging up, realized that she was really going to do it; they weren’t empty words.

Filled a bag, this and that, whatever, the stuff people bring. Line at the ticket counter, first-class ticket even though she barely had a dime, for the symbolism; she wasn’t going to arrive there like a fucking piece of trash. A little girl wouldn’t leave her alone—“Por favor, madame, por favor”—Claudine looked at her, said no, but the little girl didn’t let up, followed her all the way to the escalator. “Por favor . . . s’il vous plaît.”

Spent the train ride in a strange mood, a budding impatience that would never leave her again. For real life to begin, whatever that meant.

Leaving the train station, she’s struck by it all. The streets are enormous and packed with cars, commotion everywhere, all the Parisians hurried and stressed. She walked for hours, big eyes gazing out at the world, bag heavy and cumbersome, cutting into her palm and shoulder. At each street corner a new spectacle, imposing monuments and a flood of passersby. The smell of money was everywhere, an almost tangible current. And in her head, on a loop, I will eat you, you giant city, I will swallow you whole.

Night fell rapidly. Claudine all alone in a McDonald’s, a guy came and sat next to her. Classy shoes, nice watch, all-around wealthy appearance. He made his preliminary moves, testing the ground, judged her favorable.

He was probably used to trying his luck with young women, brought her to eat at another place. A very chic restaurant, he must have deemed her worth the money.

When she said she didn’t have anywhere to sleep, he felt he ought to warn her that he could only put her up for a night. Relieved all the same: it wouldn’t be money wasted, she wouldn’t take off at the last minute. Laughing, as if it were obvious, Claudine assured him, “I’m not going to move in!”

But she already knew that if she liked the apartment, she would stay as long as she wanted. She knew guys like him: male nymphos with a compulsive and insatiable need to be reassured, so vulnerable. She possessed everything necessary to control that kind of guy.

She played the girl who nearly cries because he made her come so good, then the girl who’s grateful to be satisfied so well, just as quickly followed by the girl who doesn’t get too attached, who isn’t too curious or too talkative, discreet signs of admiration with a zest of I’m used to people treating me like a princess so you better behave, to nurture within him a constant latent panic and the feeling that he’d nabbed a real prize.

She must have done what she needed to because the next night the man insisted she move in. She resisted a little—“We hardly know each other, we’re not kids anymore, living with someone isn’t easy”—to make sure he didn’t have any reservations. But right away he responded positively—“When love presents itself, you have to take the risk”—nimbly convinced that it inspired the same in her: a powerful jolt of rare passion. She certainly didn’t deny it.

Life at his place was pleasant, even though he wanted to have sex all the time.

Disgust locked away, instinctively, that had always been her way, her exterior was all smiles, loving and serene. It stayed inside, her desire to vomit, and a certain astonishment each time: how incredible it was that people ever took anyone at face value.

Thankfully, most of the time he went out to do things, and she was left alone at his place. Let the days go by.

Paris was a more difficult city than she had imagined. Bursting with people just like her, set on carving out a good life for themselves. So she let time pass, worked out so that her body would be impeccable when the time came. Because the moment would come, she didn’t doubt that yet.

A Sunday, winter sun, she went to the corner to buy some smokes. Long line of people at the only open tabac. A guy leaning against the bar was meticulously scratching his lottery ticket with a guitar pick. She watched him while she waited for her change. He was bland, sort of blond but not really, sort of tall but not really, blue eyes that could have been green, not poorly dressed but not well dressed either. Scraggly, nice smile, a nonchalance that suited him. Completely harmless, that was her first thought. Raising his head, he caught her eye, huge smile.

“A thousand bucks. I don’t believe it! I never win anything.”

“Maybe your luck is changing.”

“I wouldn’t go that far, but I’ll take it. Can I buy you a beer?”

He was over the moon. A radiant sparkle somewhere in the blue of his eyes. He called over the clerk, winning ticket in his hand, showing it off, proud of himself. Turned toward her again, “So, are you having something?”

She had almost said no, purely out of habit of declining this kind of invitation. But she liked the look of his face, right off the bat. She thought it would be worth it to have a drink with him, accepted.

As for Nicolas, he examined this prized knockout, amazed to feel so entirely ready to trust her.

As far as bitches went, she blew everyone else away. Her white jeans and tight blouse like a second skin, accepting his invitation to have a drink. What did she want from him, with her big tits, her flat stomach, her curved hips, and why? She had a mesmerizing ass, and she knew exactly which pants to put it in.

They threw one back at the counter. She laughed easily, seemed happy to be there. He proposed, “Let’s sit down for another?”

“Are you going to throw it all away on beer?”

“With all the debts I have to pay, it’s already spent.”

She had perfect white teeth. She played with her hair a lot, one of her ways of being ravishing.

“It’s been ages since I had a drink at a bar. Not since I’ve been here, actually, almost three months. I don’t have a dime, I can’t even buy good cigarettes.”

She waved her pack of smokes with an amused disgust. Then raised her beer to cheers him, waiting for him to clink his glass. She smelled good, he could smell her from his seat. She folded her hands on the table prudently, her nails were pink. It was impossible for Nicolas to figure out if she was dressed all trashy like this is my thing, or if she actually thought it looked good.

Later, after many more drinks, he asked her, “But why do you dress like such a slut?” Rolling her eyes she responded, “Listen, darling, you can feed me all the lies in the world, what I know is that all men adore this. Whether or not it’s absurd is besides the point, what matters is that it works every time.”

Three drinks later, she was telling him her life story: “I live with him, honestly he’s nice. That’s kind of the problem, I feel like I’m sleeping in honey. It’s fine, it’s sweet, but it’s sticky, and besides, I’ve had better. Anyway, it’s temporary, as soon as I find a way to make money I’ll get a room, even a shitty one. Sometimes, when he’s there, I go out for a walk, I look up at the apartments with balconies, huge windows, and yards in the middle of the city . . .”

And it was true, later on he’d see, when he was walking with her she would often stop, extend her arm to point out a window, “One day, I’ll live there,” and her eyes would light up, she was so sure of it, she knew how to be patient.

She kept talking, wasn’t hard to listen to. “Starting out, it’s like I’m expected to clean toilets without batting an eye. That’s the only way I can be here, on the alert, but the first chance I get, I’ll jump at it. It’ll take the time it takes.”

She chewed her bottom lip while she spoke, he noticed sometimes, asking himself if he was imagining the tears of rage that rose in her eyes.

She must not have been a regular drinker because she couldn’t control herself at all, was in a daze, her eyes staring off into space.

“Why did you come to Paris?”

“To be an actress.”

“In porn?”

It came out on its own, but you had to admit she looked the part. She just wrinkled her eyes, like she had swallowed something bitter. He stuttered, a vague hope of redeeming himself, “I really didn’t say that to hurt you, I know a lot of girls who—”

“I don’t give a shit about the girls you know, and I don’t give a shit what you think of me. I’m not so naive that I don’t know what I look like. And I’m not so naive to wait for someone to tell me what I’m capable or not capable of doing either. Time will tell where I end up. And I’ll laugh at all those people who took me for an idiot. I’ll show them.”

She stood up straight as she spoke, her entire chest stuck out against the world, and then she slouched all at once, comically, self-consciously.

“But anyway, I’m also not so naive to think I’m the only girl to say that.”

She kept quiet for a moment.

“Let’s have one more?”

“Won’t your man be worried?”

“Yeah. We were supposed to spend a wonderful afternoon together, watching dubbed action movies and smoking the disgusting pot he gets in the shitty part of town. The kids rip him off, I’m too scared to tell him. But honestly, we’re smoking henna. Anyway, you’re right, I have to get going.”

“You want another or not?”

“Just a quick one.”

The next morning, he got up to puke and she was on the sofa. He didn’t really remember how she’d ended up in his living room. They had coffee, it was comfortable. She stayed with him until she found an apartment. They became friends almost inadvertently, by virtue of always being happy to see each other and always wanting to.

Three months ago, Nicolas—who was meeting someone near Claudine’s place—went by to see if she was there. “Buy me a coffee?”

He found her overjoyed. “You know Duvon, the producer? He’s down for the record, I have to call him as soon as the demo’s ready. Listen, I think he’s really into it. The guy really wants to give me a shot. I’ve been telling you about it for a while now, haven’t I?”

He turned his eyes away from the TV screen where a guy—filmed from the ceiling for no apparent reason except to make it look shitty—approached another guy in the bathroom to shoot him in the head, calling him “my angel.”

“The demo?”

“Yeah. I lied, I told him it was almost ready. I thought of your tracks, you know, the two I really like . . .”

“Not to throw a wrench in things but . . . Claudine, you can’t sing, we’ve already tried.”

Together they had tried anything and everything to get noticed. Wasted effort. Years piled up, ambitions dampened. More than anything else, what they learned was what to ask for from the social worker, what papers to falsify to get a certain kind of assistance, how not to get audited.

“I don’t plan on singing.”

Nicolas was flipping through the channels, stopped on a commercial where a completely crazy-looking girl illuminated by green lights was on her knees in front of a keyhole, eyeing a couple. An already-outdated image.

“Just tell me up front what you’re planning to do, I’ll never guess.”

Behind him, Claudine put a cassette in the player and, before starting it, explained, “We’ll send your stuff to my sister, and she’ll plop her voice on top of the track . . . like she’s taking a big shit.”

“Your sister sings?”

“She’s not bad. I’ll play something for you.”

“You have one of her songs?”

She rubbed the back of her neck like she did when something was bothering her.

“I sent her your stuff, that we had worked on, you and me, for her to give me a couple ideas. But she made her suggestions too complicated for me to replicate on purpose. I already told you how much of a bitch she is.”

“You could have had me listen, so we—”

“No, she sings too well, it pisses me off. But I don’t have a choice now.”

She had chosen between tact and ambition a long time ago.

That was the fundamental difference between Claudine and the world. Like everyone else, she was calculated, egotistical, shit-talking, petty, jealous, a fraud, a liar. But unlike everyone else, she owned it—without cynicism, with a disarming nature that made her irreproachable. When someone criticized her, she would rub her neck. “Calm down, I’m not the Virgin Mary, I’m not a hero, I’m not a role model. I do what I can, at least that’s something.”

She pressed play.

After listening, he only asked, “Is it possible for her to change the lyrics?”

“No way. Nothing’s possible with her, she’s absolutely determined to be a pain in the ass.”

“But she’ll come here to finish production?”

“No way. She despises Paris. Which is for the best, because I despise her.”

“You really look that much alike?”

“Don’t you remember? I showed you a photo.”

“But even now you—”

“We’re twins, we look alike. It’s not that complicated.”

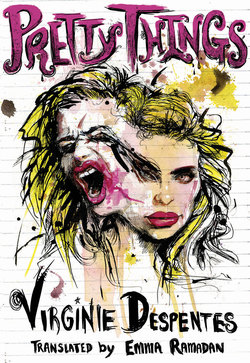

Nicolas admitted, “I really like her voice, we can make a lot of pretty things with it.”

“Singing is the only thing she’s good for. Lucky for her she knows how.”

After that, as is often the case, nothing happened as expected.

“If you’re not the one singing, what will you do?” Nicolas asked.

“I’ll do the music videos, the interviews, the photos. I’ll meet tons of people and then I’ll start acting in movies.”

“And your sister won’t say anything?”

“No, Pauline can’t stand anyone except for her boyfriend and two or three of her friends. I’d be shocked if she was angry about not being in the spotlight.”

When the tape was done, Duvon thought it wasn’t bad, just needed some modifications. Modifications made, there were still two, three things that he wanted to see changed. At this third stage he had shaken his head, very disappointed. “That’s not it, that’s not it at all . . .”

From that moment on, he became unreachable by telephone.

“Yet another thing going wrong,” Claudine commented soberly.

But the tape made the rounds, some kid ended up calling her back.

“Well, some kid, he was definitely at least thirty, but he was in Bermuda shorts . . .”

One year later, she and Nicolas were walking along the quays, the leaves were starting to turn green, the girls were showing off legs they had already tanned, and a lot of people were out walking their dogs.

“He said, ‘Come to my office,’ so I showed up. I couldn’t stop laughing, it was a totally disgusting closet with filthy junkies doing nothing but pressing buttons on the fax machine. And him, in Bermuda shorts. Pretty pleased with himself . . . I swear, it’s too bad you didn’t come, you’d have been cracking up. His label sucks, just shitty bands, his office is dirty, he dresses like a moron, but he’s so fucking pleased with himself. As if he’d accomplished something. If the point of the game was to be a fuckup, then there’d be something to be proud of . . . birds of a feather flock together, you’ll tell me, I’m sure.”

“You think he’ll make the record?”

“He says he will . . . he thought the lyrics were ‘so cool.’ I swear, I couldn’t keep it together, the lyrics—what an idiot. Then he said to me, ‘I’ll do the record,’ happy it won’t cost him a lot, and he doesn’t even know how to do promotion. Regardless, I signed the fucking dish towel he called a contract, we have nothing to lose, right?”

“You told your sister?”

“Yeah, yeah. She knows the guy’s company, she knows all those shitty labels. She said it was cool, for once she didn’t burst into tears. Maybe she’s going to commit suicide.”

“And she knows that you’re saying you’re the singer?”

“Yes, I told her. She’s so sweet, she said, ‘Go ahead, with all the talent you have, you have to appropriate wherever you can if you want anyone to pay attention to you.’”

“You’re right, she’s so generous.”

“It’d be nice to think she’s wrong . . .”

“Are you having a little bout of depression?”

“No, I don’t give a shit. I’ve told you there’s rarely a link between talent and success. I haven’t lost hope.”

“What if there’s a concert?”

“There won’t be. Maybe there’ll be naked photos of me all over the place, but there won’t be any concerts. For a start, if he manages to put out a CD, I’ll be blown away. Want to go sit outside?”

Someone’s playing the guitar downstairs. Deep chords stretched over a background of repetitive, sad sounds.

Claudine complains it’s giving her an earache, she washes down her painkillers with Anjou Rosé. She’s been drinking for a while. She walks around her apartment barefoot, soles black with dirt.

Sitting at a bit of a distance, magazine open on the table, Pauline watches her, disgusted. Noise from the window, she glances over. Meat truck, a dumpster filled with pink and white. Some ladies are talking next to it, unidentifiable language, they’re wearing elaborate dresses, summer colors, suddenly break into intense laughter that never ends.

Nicolas calls a friend, keeps flipping through the channels. On the screen, flashes of athletes dripping with sweat; zealous, pert, and abrasive female TV presenters; a prudent political man; a blond kid in a commercial.

Seated next to him, Claudine rips apart a cigarette. As soon as he hangs up, she asks, “So? Did he feed you a bunch of bullshit?”

“Less than usual. He seemed off. He was really disappointed you didn’t want to talk to him.”

“Absolutely nothing to say to him.”

“In any case, you’ve certainly got him hooked.”

“That’s all they want, all of them. To collect women, it’s the only thing that gets them off.”

“You thought he was so smooth two weeks ago.”

“I remember. But I must have some molecule, it’s ridiculous, some thing that turns people into total losers. You take the coolest guy in the entire city, seductive, funny, open-minded, you leave him with me for one night and the next day he’s dead weight. It’s inevitable.”

By now, he knows her little mean-girl schemes. Whether she sleeps with him or not, a man is still her worst enemy. The first time she lands a guy, she’s as nice as a babysitter, all smiles between two blow jobs. Until the day she disappears. She pulls that move almost every time, to make them realize how attached they are. When she comes back, it turns serious, and the guys pay. Until the day it’s no longer enough for Claudine: the gifts, the attention, the acts of love. Then, the final phase, she declares that not only is she seeing someone else, but she fucking loves it. Feigning sincere distress, she lets slip, “If you knew how hard he makes me come.”

Nicolas takes a drag of the joint, coughs a little, remarks, “I’m glad we don’t sleep together.”

Claudine grabs the remote and looks for a channel with music videos.

“That would never happen, I’m not your type.”

His type? He made a point of not fucking girls who think they’re beautiful. Just to piss them off, those girls who think they have the irresistible gift of seduction. He figured out long ago that he’s hot, that people really like him, without actually understanding why. He likes nothing more than getting a skank all heated up, until he can feel her really burning. Then not touching her. On the other hand, he has a weakness for homely physiques, the injustice of it gets to him, he really enjoys taking care of them, unearthing the good in them. At the very least he can be sure he’s not the umpteenth guy to make them meow with his pelvic thrusts.

Claudine turns toward her sister, hands her the spliff.

“You still don’t smoke?”

Pauline briefly signals no, her twin looks at the clock, adds, “It’s almost time . . .”

Her sister doesn’t even bother to respond. She continues reading, Nicolas turns his head toward her. It’s still difficult for him to admit that this boring nerd, hair as lackluster as her skin, dressed in a sack, her gaze black when she wants something, really looks like Claudine.

Who says, “You okay, sis, not freaking out too much?”

“What the fuck do you care?”

“Wow, you’re a real barrel of laughs.”

“We can’t all be a joke like you, Claudine.”

Solid mastery of contempt. Nicolas stifles a snicker, elbows Claudine, convinced it’ll make her laugh too, since she’s normally so easygoing. But Claudine doesn’t take the opportunity to laugh it off lightly. She usually makes fun of everything, or at least puts up a front, but she takes it badly this time, not even trying to hide it.

She swallows painfully, squints, spits out, “I guess we can’t all be human either.”

Her sister rolls her eyes, smirks slightly, snaps, “With how deranged you are, it’s hard to feel any sympathy.”

A few tears run down Claudine’s cheeks, she doesn’t even wipe them away, as if she doesn’t feel them. Nicolas racks his brain, how to intervene tactfully and stop things from escalating. At a loss, he turns to Pauline, hoping she’ll stop her bullshit. Pauline gets the hint, shrugs her shoulders. “She always was a crybaby.”

Neither spoke another word to each other after that. Nicolas flips through the channels, pretending to be absorbed by a wildlife documentary. When it’s time to go, Pauline gets up, stands in the entryway, waits for Nicolas. He looks her up and down, not wanting to believe it.

“You’re planning to go out like that?”

“Yes. I do it every day.”

“You have to put on your sister’s clothes!”

“Don’t count on it, asshole, I don’t dress like a slut.”

“No one’s going to believe she’d go onstage like that!”

Nicolas, who saw Claudine often, had never seen her without makeup. Even when they slept in the same place, she made sure to get up first and get ready in the bathroom. Not to mention her obsession with clothes and the time she spent putting together the right outfits . . .

“Believe it or not, you can actually go onstage without dressing like a groupie.”

“Have you heard of a little something called a happy medium?”

“That’s for cowards.”

He turns toward Claudine, counting on her support. She shrugs her shoulders in a sign of helplessness.

“Don’t push it, there’s no way. You shouldn’t worry about it, there won’t be anyone who knows me anyway, it’ll be like I had a sudden grunge crisis. Could happen to anyone.”

With a forced smile, without a shred of enjoyment. She accompanied them to the door, Nicolas lingered on the landing, still hoping for a word of goodbye that would ease the tension. Claudine barely looks at him, murmurs, “Don’t worry, everything will be fine.”

Monotone voice, closes the door, without the slightest sign of complicity.

Following Pauline down the stairs, he starts to detest her so badly he feels solidarity with those people who corner girls and force them to shit their little panties before using those same panties to suffocate them.

Rue Poulet smells like a butcher shop, whole creatures hanging from hooks. Women talking in front of packed displays of vegetables. On car hoods women sell underwear to other women, gesticulating, bursting into laugher, or throwing tantrums. A giant man lifts up a thong to get a better look, black lace stretched in the sun. Sidewalks strewn with crushed paper cups from KFC, food wrappers, green takeout boxes. Farther on, a guy sells pills in little plastic baggies.

It’s not easy to get by with so many people on the sidewalk.

Accompanied by Nicolas, who’s pouting because she didn’t want to change, Pauline heads toward the metro. He shakes his head, pointing toward the taxi stand on the opposite sidewalk.

“I can’t take the metro, I’m claustrophobic. We’ll take a cab, it’s not far.”

She rolls her eyes, follows him without saying a word. His stupid struggle, the metro stresses him out. I don’t give a crap about your whiny bullshit.

Her disdain evident since her arrival, her every look has been critical, condescending. She knows everything and judges instantly. How he would’ve liked plenty of disgusting things to happen to her, to break her in two and make her understand that everyone is doing what they can and that she isn’t any better than anyone else. It’s all relative. It’s easy being perfect when you live under a rock.

He stares hard at her profile; they both have the same features. It only adds to his dislike. As if she’d stolen something from Claudine, something precious: her face.

There’s always a truck at the street corner, either the cops or the Médecins du Monde.

At eight o’clock the doors of the Élysée Montmartre are still closed. The sound check is running late. A few bouncers are going up and down the stairs with worried looks.

At regular intervals the metro spits out people who clump together on the sidewalk, filing into groups. Some people recognize and call to one another as if they’d just seen each other yesterday. No one thinks of complaining about the wait, unexpected and prolonged. Sometimes someone turns their head, deceived by a murmur in the crowd, gets up on tiptoe to see if it’s moving, but it still isn’t moving.

A woman carves out a path through the crowd, a kind of stubborn urban crawl. A bouncer listens to her sweet-talking—they’re waiting for her inside for an interview—lets her flash her press pass. He pulls out his walkie-talkie to ask what he should do with her. He takes advantage of the wait to get a good look at her cleavage. Not because it actually pleases him, to look at her tits, he mainly just likes to make a show of it in front of his friends. As soon as she turns around, they’ll have a good laugh about it.

The guy who works with him avoids meeting her gaze. Embarrassed for the man who skewers a woman like that, embarrassed for the woman who exposes herself like that. And embarrassed for himself because his eyes can’t help themselves, they spring up and land on her. Every time he sees a woman like that—which is every time he works—he asks himself where it is she wants to go. He lets her pass, she climbs the stairs leading to the concert hall, pushes open the doors, and disappears. She scours the hall, looking for someone she knows.

She heads toward the food. Approaching the stage, she recognizes Claudine. That bitch made herself look like a total dyke. Some people aren’t disgusted by anything.

The journalist scampers toward the stage, ecstatic at the idea of approaching her, of Claudine coming to shake her hand. Not that she would be happy to see her, they barely know each other, and the snob is hardly friendly.

Nicolas intercepts.

“Save your breath, she doesn’t want to see anyone.”

“She’s getting a big head already?”

“No, but she’s freaking out. Anyway, how are you doing?”

She could have smacked him. And that whore, up onstage, pretending not to see her and acting like someone who can sing. Whatever, it’s not like they just filled the Zénith, she’s only an opener. She acts like she isn’t bothered.

“Listen, it’s dumb, but I really wanted an interview. I can still talk to her after the sound check, right?”

“Not today, she’s on edge, she doesn’t want anyone to talk to her. You know, to really concentrate. But tomorrow, if you want, she’ll give you a call.”

“Tomorrow? That’ll be too late. I’m afraid I’ll be too on edge.”

She turns on her heel and goes directly to the bar and orders a whiskey. Contemptuous anger: What is this bullshit? Does she want us to talk about her or does she want to die in obscurity? She didn’t even sell a thousand copies of her album and it’s turned her into this. But she knows very well that when creatives and journalists have common goals, plenty of things are forgotten.

Nicolas watches her walk away. For the moment, no one suspects a thing. Until now he’s only experienced this level of absurdity in dreams.

Just then, the label manager worms his way to Claudine-Pauline. He congratulates her for a while. “Everyone’s crazy about the album, I’m so happy to have done it.” Standing nearby, Nicolas’s heart comes out of his chest and he imagines causing a diversion by throwing it on the ground. But Pauline gets herself out of it, retorting, calm and dry, “Shut your fat mouth, I don’t want to listen to you talk anymore.”

Instead of being furious, Bermuda Shorts blushes, starts stammering, perfectly cheerful. “Well then, she’s got some balls, huh, when she wants something . . .” in a very administrative tone, which he never used while talking to the real Claudine, who had always made an effort to be friendly.

Nicolas walks across the entire venue, explains to the sound guy for the third time that it doesn’t make sense to put the vocals so far up front.

Three hours ago, he couldn’t have imagined that he would make all these back-and-forths because the sub-bass this or the equalizer that.

Pauline is onstage; hands crossed behind her back and eyes glued to the floor, she begins to sing.

Stiff, not smiling, and dressed like garbage, she becomes rather dignified. Quiet metamorphosis, impressive to see. As though it were coming to her from afar, these things pouring out of her mouth, so self-assured.

Nicolas climbs onstage. “Is the feedback okay?” He cautiously wraps the microphone in fabric. Then moves away and asks her to sing again. “Can we try another song?” In passing he argues with a guy from the venue who wants to stop the sound check immediately because they’re running late.

He quickly adjusts one last thing, jacks tangled up everywhere, the hall empty, stands exactly where he needs to be to hear all the sounds, since he likes the sputtering from the walls, the knobs, the red lights, adjusting the mic stand, the guys hanging off the scaffolding to adjust a projector.

Like something you don’t even dream about anymore, to avoid the taste of bitter awakening.

The guy from the venue turns plain nasty. They need to open the doors so the concert can begin.

Nicolas meets Pauline at the edge of the stage, notices her hands trembling. “I’m going to buy some smokes, I’m all out. You want to come with me?”

She shakes her head no, immediately reverts back to her usual demeanor; it makes him want to slap her. In any case, he’s relieved when she refuses because he actually just wants to call Claudine from a quiet corner. Reassure her, tell her that everything’s going well. And then a sort of guilt, this pleasure he gets from handling the sound check, as if colluding with the enemy.

“You want anything?”

“To be far away from these idiots.”

Impossible to understand where her anger stems from. No one had spoken to her, no one had done anything to her. But it’s not faked, she seems completely put off.

“Wait for me in the dressing room?”

“No, I’m going to shut myself in the bathroom. That way no one will talk to me. Come get me when you’re back, I’ll be in the one that’s to the right when you come in.”

“Everything okay, Pauline? A little stage fright?”

She stares at him hard, glacial. “Don’t forget that we aren’t friends.”

That little surge of guilt he had felt from enjoying working with her disappears all at once. Crazy bitch.

THE THINGS IN her apartment are covered in a thin, viscous layer. Claudine washes her hands, the towel she uses to dry them seems greasy too. That happens, some days.

Sun, Xanax, enveloped in an almost absurd calm that makes her gently sweat, clammy torso and back. Her eyes close, are heavy underneath.

Nicolas just called: everything’s going well. Not a surprise. Pauline has always been like that: successful at anything she sets her mind to. She can play the girl with a nasty attitude who’s bored when she gets onstage. She knows her voice is good, she wants all the world to know. So she’ll put on a good show, even if it’s her very first.

Kitchen. Coffee rising, burbling up in spurts. The seal is busted, light brown bubbles leak out the sides. The coffee maker needs to be replaced, Claudine never thinks of it. Now that she has, she feels a slight pang in her heart because it no longer matters. Fear doesn’t have much of an effect on her, just a small trace of bitterness.

She spills some coffee over the side, wipes it up with the sponge, which is slightly black from being poorly rinsed. She doesn’t give a damn about household objects on principle: not to be like her mother.

Don’t go, I’m begging you, don’t go, there are things in life that you don’t do, don’t go . . .

Window open opposite, the street acts like a loud speaker, Claudine hears a song as if she were listening to it in her own apartment.

Sharp attacks tearing her apart, the same headaches of the last few days, but the banging is getting worse, less bearable.

Pink stain of the curtains, the sun setting. Irritated voices below. Reflexively, she leans out the window to see what’s going on.

A man, back to the window in the butcher shop, two men and a woman facing him. It’s the woman who’s speaking, she’s furious, hair covered, pink dress down to her ankles. The two men with her shake their heads to signal that they disapprove of what the third is doing. Impossible to know exactly what’s going on, they’re not speaking French. She can’t see them well from so far away, but the man with his back against the security gate doesn’t seem scared.

The flowers have started blooming in the last few days, hanging from other windows.

Her breath shortens, cuts off if she isn’t careful.

How much longer are things going to be like this?

Luck doesn’t change. It’s all bullshit.

On a table, a photo of her and Pauline. They’re nine years old, it’s the only photo where they’re together and dressed the same. It looks like a silly special effect, like a hidden mirror reflecting one face. Two queens on the same card.

She feels that terrible surge that passes through her from time to time. Anger, and she needs to retrace her steps to account for it.

Her father would repeat, “They certainly do look a bit alike, and yet they don’t look alike at all,” letting a knowing glance fall over Claudine. Supposedly he didn’t talk about that in front of her, to avoid hurting her, supposedly he took precautions, because she couldn’t do anything about it. She was the one who was not very clever, frankly, not very smart.

Sometimes her father invited friends to the house, called the two girls over. Secretive conversation, so they wouldn’t hear, as if they didn’t understand anything at all. Then he questioned them, to demonstrate to the audience how studious Pauline was: cunning, mischievous, and so sharp. And next to her, her sister, who never understood a thing. She did a bad job on her schoolwork, never connected anything with anything, couldn’t convey the desired information. Filled with shame in front of these strangers, she had to open her mouth, say something, if she didn’t say anything her father leaned in toward the other adults, said something mean, disparaging.

And her bitch of a mother, rather than defend her daughter, rather than put a stop to all of it, would bring her to bed immediately, infuriated at seeing her be so stupid. The next day, to console her, she would put her hand on Claudine’s forehead, “It’s not your fault, my angel. With twins there’s always one that picks up the defects . . . my poor angel, there’s nothing you can do.”

Her mother’s stomach wasn’t big yet. She had just learned that she would be having two.

Her father was enraged. Since the beginning of the year her mother had been working, like him, as a teacher at a junior high school.

Before that everything had been clear, easily summed up: he had married an idiot, oafish and dull.

Of course, there were those weeks right after they met when her father would lean toward her—“You are my happiness”—and kiss her nonstop, craft compliments sweet as candy, talk dirty, he couldn’t get enough of her.

And then slowly, as if he were opening his eyes, she became this meager thing. Inept. He didn’t leave her, didn’t cheat on her. He never got tired of watching her mess up every single thing she tried. Never got tired of watching her dress poorly, he who was so fond of elegance. Of hearing her speak poorly, he who so loved intellectual things. Every gesture she made was reproachable. Even her way of rinsing a sponge, of hanging up the telephone, of wearing a skirt.

He never got tired of watching her be so pathetic. And he pitied himself, to have fallen for such a woman. And without ever lifting a hand to her he went after her with all his violence, his entire being focused on demeaning her.

He wouldn’t leave her alone until she cried. And as soon as her eyes watered, his fury would begin: How dare she complain? And what did she know of pain, the burning he felt?

The same way he demanded all the space in the bed, his own distress demanded all the space. He was the most, as a matter of principle. The most tortured, the most sensitive, the most in touch with his emotions, the most reasonable. The one of the two of them that counted, the one at the center.

She possessed only the right to listen to him because he loved to talk for hours. It was her duty to listen to him even if his words destroyed her, implied she was worthless, even if his words suffocated her, never left her any space.

And her mother let it happen, made herself sick, like a woman, in silence. Her body eaten up in big chunks that never completely disappeared, vomiting, careful not to make any noise, at night her ruined sleep knotted up her throat. But above all she would never complain, because he suffered so much. Compared to his experiences, hers were garbage, just showing off her melancholy, who did she think she was . . .

One day, she started teaching, like him, in the same junior high school. And in one year, everything switched.

Her mother turned out to be a good teacher, in any event perfectly capable of keeping the kids in check for the duration of class.

He had always been pretty mediocre, neither loved nor feared, interesting to no one, especially not to his students, who mocked his drinking; rather than picking up on the desperate beauty of the gesture, they picked up on his breath and used it to fuck with him.

And so one day, her mother, correcting homework, was interrupted by her father who, leaning over her shoulder, shared his opinion on a comment she had just written. Without even raising her head, frowning, concentrated, she replied, “Excuse me, but I think I know what I’m doing.”

Her father’s wrath was terrible. At first he tried to make her apologize, but since she persisted he started breaking things and insulting her like he never had before . . . the idea that she could even think of opposing him was intolerable, that she could draw the strength from somewhere to believe in herself in spite of him.

The rage of powerlessness, like a child’s tantrum, took hold of him that night and for the first time he moved from threats to action, started breaking everything until she begged, fear in her eyes, until she was the first to give in.

Her mother quit teaching, shaken by having hurt him so considerably for a job that, in the end, didn’t interest her all that much.

But her father stayed angry. He had always pulled out when he felt himself coming and ejaculated on her stomach, because he was too young to have a kid and because he wasn’t sure—far from it—that he wanted to have one with her. From that day on, he started fucking her like he was nailing something into the ground, all the way inside so she would get a fat stomach and stay put.

But almost as soon as she was pregnant, her mother began to rise up and get comfortable with him. Supposedly she knew better than him about certain things regarding her condition. “Because I’m a woman,” she would reply, shrugging her shoulders. Her mother proposed that they call the twins Colette and Claudine. Her father was firmly against it; she didn’t concede.

“Then we’ll each choose one name.”

And so it was done, her stomach ripped in two.

THE VENUE IS filling up. Security regulates the flood of people, the bouncers glance in their bags, make them take off their jackets. It serves no purpose, to tell the truth, but it’s part of the ritual.

At the top of the stairs people meet and chat, share rumors and opinions about what’s going on. The stoner version of a social gathering, most of them are overly done-up: bleached pierced tattooed gap-toothed scarred high-heeled.

Nicolas moves through them, making himself look like he’s in a hurry because he doesn’t want to run into any old friends. It gets him so down, every time, makes him confront the reality of aging when he sees old faces again. Already a little wrecked, withered, fatigue settling in, and cynicism to top it all off, extinguishing what’s left of their gaze.

Pauline, sitting fully dressed on the toilet seat, smokes cigarette after cigarette. She regrets being there. She’s dreamed of this moment for a long time. But it was nothing like this. It was her own name, and Sébastien was there, backstage, proud of her as he heard her sing. And it wasn’t in front of these idiot kids who’ve come to have their souls sodomized, ready to swallow any subversive commodity as long as it makes them think that it adds something to their identity.

Mainly, she misses Sébastien.

Chest strained by his absence, she remembers and lists the best things about him, like a little internal song playing on loop.

The first time she saw him she didn’t really give a shit about him, he seemed like kind of an idiot.

Older than her, he had a car, drove her home.

Then there was that day: he brought her to her place and, sitting on the hood of his car, told her jokes. Claudine showed up, gave him her number. And when she walked away, Seb had remarked, “It’s funny to see the two of you together. Your sister is super pretty. But she doesn’t have what you have.”

He was neither flustered nor aroused; he was the first boy to resist her sister’s charms. To prefer her, Claudine’s sister. So, in his arms, she realized that he was her entire world. And since then, nothing had ever weakened the hold he had on her.

Until one night in March, she had been waiting for him, irritated that he was late. They were supposed to go see a movie and he wasn’t very excited, so she was getting annoyed looking at the time, convinced he was doing it on purpose. Then night fell and worry kicked in.

The telephone rings, the lawyer calling on his behalf. He was picked up that morning, in the papers they’re calling it a “big catch,” he’ll have his sentencing soon, he doesn’t know how much time Sébastien’s facing, he can’t answer any of her questions, it depends on who he does or doesn’t give up. The lawyer has tact, a distant politeness, but doesn’t care at all, just fulfilling an obligation: notifying the girlfriend of one of his clients.

Clean break, everything on hold.

FROM THE OTHER side of the door, some of the people working the bar are getting riled up talking among themselves.

“This crowd pisses me off, they’re always trying so hard to be fashionable.”

Another voice, from elsewhere. “When it’s the Americans doing it, everyone thinks it’s so cute, but when it’s the French it’s not funny anymore.”

Aggressive tone, between people who have already been drinking, trying to convince one another without seducing one another, sterile conversations that make up mosaics of meaning. Everyone is actually saying something different. An unhappy ex-child interjecting at every opportunity—sometimes while trying to affirm something, something else emerges—little pieces of poisoned cakes that we’d rather spit out.

Two girls loiter by the sink for a bit, she listens to them talk. They’re probably washing their hands, touching up their makeup, redoing their hair. One of them says, “Two-hundred-thousand-franc advance, that’s not nothing.”

“But is the money for them or for gear?”

“It’s for them, to get them to sign there instead of somewhere else. It’s an advance against what the label thinks they’ll sell.”

“Two hundred thousand! Just like that, your problems start melting away.”

“I’d certainly hope so . . .”

“For all the time you’ve spent slaving away, he must have no shame.”

“That’s definitely him: shameless. You’ll never guess what he told me. He’s going to give me two thousand a month—to pay the bills.”

“No way.”

“Oh yeah, he’s a kid, this guy, he doesn’t understand that he could pay the rent too. For him, money is pocket change, it’s for buying his toys. I have to say, maybe I did let him take advantage of me.”

“Still, with two hundred thousand, you’d have to be really stingy to only give away two.”

They leave.

Then Nicolas’s voice. “You in here?”

And as soon as she opens the door he tells her to wait five seconds. While he pisses he says, “It’s nerves, makes me have to piss every five minutes. Does that happen to you?”

It’s only right then that she puts a name to what she’s feeling: panic and fear, like being up on the highest diving board. That emotion deep inside of her, anxiety mixed with a terrible desire to be elsewhere, to backpedal. And mixed with impatience, too, to feel its effect.

Pauline follows him backstage, asks, “Is it really possible for someone to give you a two-hundred-thousand-franc advance to make an album?”

“It’s possible, but it doesn’t happen to everyone.”

“You’d need to already be famous?”

“Yeah. Or make everyone really like you.”

SHE’S THREE STEPS from the stage, standing where there’s no light. First rows of the audience, people gathered together standing and talking, red tips of cigarettes, general commotion. Two sound guys are moving around again onstage, taping up one last thing, moving the floor monitor a bit. She no longer feels her legs, nothing but her throat, it’s like a chasm inside of her, she doesn’t want to go onstage. Yet she’s crippled with desire to be there, it makes her tremble through all her limbs.

Someone tells her she has to go on. She’s in another time, no consciousness of anything, a moment when she does things automatically, hypnotized.

The stage plunged into darkness, the people below form a sort of flow of faces, a murmur runs through the crowd when she walks onstage.

She won’t be able to do it. Or even move an inch, or even open her mouth. Spotlights on her, blinding, and the track begins. She has the time to think, I’ll forget the words and my voice will never come out.

She’s ashamed of being there and of everyone seeing her. She feels ridiculous, humiliated, exposed. And with absolutely no reason to be there, planted there, under the eyes of all these people. And where to put her arms and where to put her legs and how to disappear, not have to do this.

Nicolas looks at her, he’s in the shadows at the bottom of the stage doing her sound mixing. He worries that something’s going wrong but nothing’s going wrong.

It’s obvious that she’s uneasy, awkward. The majority of the people in the audience don’t even try to listen to her, they talk, wait for the real band. Some faces, in the first row, are attentive, heads moving a little. That’s a start.

Even so, that voice of hers is so fucking rousing. It’s not so much that it’s well trained, but that she knows how to unleash it.

PAULINE AND NICOLAS go back home on foot. The sidewalks between Pigalle and Barbès show no signs of emptying, storefront lights, a mass of people. Some going to the prostitutes, others to have a drink, others to a concert, to the movies, to visit someone, to eat somewhere. All kinds of people doing all kinds of things, like a big machine with everyone in their own track.

Nicolas drank quite a bit right after the concert, a backlash, the need to blow off steam. People around him, assailing him backstage, clamor of compliments, some sincere. Pauline was waiting for him, shut away in the can again. He claimed, “I don’t know where she went,” and so many people wanted to see her, puking up flattering words. Some insisted more than others, they really wanted to introduce her to so-and-so, playing the helpful middleman. He couldn’t even leave, a crop of business cards and numbers scrawled on packs of smokes. Small success. Overwhelming.

He suggested to Pauline that they go back on foot, he needed the night air, still a bit cold, the boundary between the seasons. He talks to her on the way, mechanically.

She hasn’t said a word since she walked offstage. Not one rude remark.

They turn down Boulevard Barbès, the street empties. To the right, the Goutte d’Or neighborhood like a chasm.

Fire truck sirens sound in the distance, get closer, turn into a racket.

Nicolas comments, “It sounds like they’re headed somewhere nearby, maybe someone died. Last summer a guy got stabbed right below Claudine’s window. They blocked the street, like in a Hollywood movie, and outlined the body in chalk on the ground. It was weird, you know . . . I was watching through the window, not the TV. They tinkered with two or three things, and then they removed the tape and in the blink of an eye people were on the street again. It was like life closing up over the dead guy.”

There’s a crowd at the end of rue Poulet.

“It’s on this street!”

He walks faster, excited, but also concerned. “I hope it’s not a dead body . . .”

Pauline listens to him blathering on, feels like he’s trying too hard to act like a kid from the streets for it to sound believable.

They arrive at their destination, orange-and-white plastic tape stretched between them and the door.

Nicolas lifts his head, looks for Claudine at her window.

“Oh, she’s not there. I’m surprised, with how nosy she is, this would be a jackpot for her . . .”

He signals to a guy in uniform, “Excuse me, we live here, can we go in?”

“Do you have ID?”

“No. We didn’t realize we’d need ID to get back into our apartment. But there’s someone waiting for us, who can—”

Pauline had pushed through the crowd, stopped at the tape. She turns toward Nicolas. “She won’t be able to do anything at all.”

He understands immediately, feels it in his stomach. One of the cops looks at Pauline, speculates delicately, “You’re family? My condolences.”

Stupidly, Nicolas reflects to himself that he really is the only one who doesn’t find their resemblance striking. She hesitates, should respond with the truth but, coming from a concert where she was supposed to be her sister, doesn’t know what to do. Her confusion passes for grief. The cop lifts the tape, signals for her to come through, announces, “She jumped. Some of the neighbors say they saw it happen.”

A man asks her name, she says, “I’m Claudine Leusmaurt.”

Nicolas flinches, a little belatedly, would like to intervene but she’s already ahead of him.

“I’m the one who lives here. My sister arrived yesterday, we almost never see each other. It’s a stupid thing to say but . . . I’m not all that surprised.”

The man asking the questions scribbles some things in a notebook. He’s doing what he’s seen done in a lot of movies, adopting the gestures and mannerisms that seem appropriate for the occasion. Except it’s obvious that he’s bored shitless, thinking only of the forms he has to fill out. He snorts, asks, “She was alone up there?”

“Yes, I just got back from playing a show. She didn’t like crowds, she didn’t want to come.”

She doesn’t feel any emotion, except for something like hostility—she always has to be a pain in the ass—mixed with a joyous remorse. It’s the third time she’s wished for someone to die and it ended up happening: first her mother, then her father, finally Claudine. An empty space all around her, those who had to pay have settled their debts.

It’s odd to see the living room completely filled with strangers busy with various things. Just like that, the room is transformed into a stage set, a normal place on pause, people fretting all around.

A man who must be a detective tries to get Nicolas to talk, but he’s leaning against the window, doesn’t say a word. Pauline is sitting in a chair, she intercedes, “He’s really emotional, he must be in shock.”

She gets up and takes him by the arm. “Go home.”

She takes his hand, squeezes it to the point of crushing it, and fixes her eyes on him. For the first time since her arrival, she plunges directly into him, he smells like metal. Her grip and her gaze, all authority. She asks, “Call me tomorrow?”

She waits for him to walk away.

Then, to the detective, “He didn’t know her at all, she doesn’t live in Paris. Get out of his hair and let him go.”

“You can say she didn’t live in Paris now.”

“You’re just chock-full of tact, aren’t you, asshole.”

He’s set her off, a familiar feeling, she screams, “Son of a bitch, motherfucker, my sister just jumped out the window and you’re saying shit like that? How fucked in the head do you have to be to act like such a dick?”

Finished screaming, a slight wavering. Those present seem tired, and must not like their colleague because they mostly take her side, understand where she’s coming from.

They let Nicolas go.

She thinks over it all, the things she has to pay attention to in order not to contradict herself, not to betray herself. Now that she’s become Claudine, she mustn’t make a single mistake.

HE WENT BACK home to his 195 square feet. He sat down in the armchair that he reclines to sleep in. Put on his headphones and a CD. Still shocked.

He feels in him somewhere the stupefying banality of trauma. That efficiency cutting a life in two. A few seconds suffice to sum it up in one phrase: everything has collapsed.

He hasn’t cried since he was little, he would really like to tonight. He doesn’t know what it’ll do for him, but like everything he’s deprived of he lets himself form a splendid idea of it. He remains immobile, lets the ideas pass through him. They come and go, those flaying emotions, as they like. He doesn’t have the energy to seek them out, nor to classify them, nor to shield himself from them.

He feels incredibly guilty. For not having guessed. The one time she let her true self be seen, he put off dealing with it for another day.

He feels it already, he knows he’ll be angry with himself for a long time for having enjoyed this night so much. And when they walked back, he remembers clearly, somewhere in his mind he thought about how he should act, how to tell Claudine about the concert, thought of leaving out certain things to keep from hurting her.

But above all he regrets not having taken Claudine for a walk wherever, somewhere calm where she could escape her anxiety, switch it off. Reproaches himself for not being able to say, “Come on, we’re getting on a train, we’re getting out of here, I think you need a break.”

There’s a thought running through his head, repugnant and thoroughly misplaced, but a thought that comes back regularly, a nauseating regret: Why didn’t she leave me a note? And: Why didn’t she wait for me, give me a chance to help? Did he not matter at all, not have any impact on her life, not make any notable difference to her despair?

He had suspected something for weeks, behind the vestiges of agitation, something barely visible. He had noticed very clearly the pain intensifying inside her. He didn’t have the courage to get involved. He thought it would ease up on its own, as often happens. The demon falls back into its slumber. He imagines a sort of bird, red and fiery, with a gold beak, ripping apart her chest, demanding that she surrender herself entirely to it that night.

Was it necessary, inscribed somewhere precisely what had to happen? Or was it nothing at all, all that was needed was a noise opposite, a phone call, a guy she likes on the TV, and the moment would have passed, would have been just like the others.

Did she have time to regret, the second after she had done it, to want to hang on, deny the evidence with all her strength and believe again in the possibility of survival? Did her life flash all at once before her, at the same time revealing and outlining who she was?

SHE SLEPT THE whole day, the noises outside mixing into her sleep. Woken up by an argument, she got up, groggy, glanced at the street. A man trying to hit a woman holding a kid in her arms, she insulted him while dodging his blows, ran away, the kid crying and extending his arms toward his father. Went back to sleep. The smell of the sheets made her vaguely nauseous. The sun struck her eyelids. The telephone in the next room rang and rang, tentacles of voices coming through the answering machine.

Then the day no longer filtered through the double curtains, she got up to eat something.

Muted and pure hostility, Claudine had always managed to piss off the world. Whatever scheme possible to attract attention. What happened that night was that she was so repulsed at not being the one under the spotlight that she preferred to go out the window. Sick with jealousy and always wanting to get herself noticed.

The whole night was tiring, a lot of strangers to deceive. In a trance, pretending she was Claudine, a sort of blind reflex. And she repeated to herself, “That cunt thought she was trapping me, but she’s actually done me a huge favor.”

Because that suited her just fine, to pass for her sister long enough to sign a record deal. That talk of an advance had been on her mind since she overheard it. She’ll get an enormous advance and barricade herself in with the spoils. It came together little by little, a terrible confidence. Her sister knew people, Pauline would use her contacts and settle the deal in a month. Before Sébastien gets out, she’ll have a fortune and they’ll go off together far away from here.

But now she’s alone like an asshole in this apartment. Alone for the very first time, with a heavy feeling, like she’d been drunk and done something really stupid.

Things left here, everywhere: open books next to the bed, pens, lipsticks, dirty glasses with alcohol hardened to the bottom, sweaters, a paper towel tube, coffee tin, empty packs of cigarettes . . .

In a corner of the living room, there’s an entire wall of Marilyn Monroe. In every pose, at every age, from every angle, the Marilyns smile, lean toward the lens, want something, we don’t know what, give the essential thing, a version of herself that doesn’t exist. Just the day before, discovering this monstrous collection of clichés of the blond flaunting herself, Pauline felt mournfully indignant toward the childishness of her skank sister, who couldn’t understand that what she was doing would only lead to disappointment.

Today, alone in the unfamiliar apartment, she thinks about tearing down all the photos, carving out some order in the pathetic chaos. But her sister is no longer there and it doesn’t make any sense. Like many other ideas that come to her spontaneously, abruptly stripped of their logic.

Equilibrium needs to be restored. It was constructed opposite her sister, a force exerted on another. She has a clear image in her mind: two little women in a bubble, each pushing with her forehead against the other’s. If one of the two little women is removed, the other immediately topples over, falls into the other’s domain. A blank space, a void is created in her; in one night everything has shifted.

Noise outside, she stands at the window. The street lures her every ten minutes, the omnipresence of the outside. A kid runs, zigzagging through people, two cops run after him. Gendarmes and thieves. Passersby freeze, watching the action. Then the trio returns, going the opposite direction, handcuffs on wrists, flanked.

The day they arrested Sébastien, did they parade him around like that, in the middle of everyone, captured?

It’s not just her at the window; all along the road, people lean out to observe and no one intervenes, no matter what.

To keep herself occupied, she puts on music and dances. She’s always done that, danced just for herself. Sweat appears slowly, first on her shoulder, then her back, finally her thighs are moist; breath, heels, hips, and arms embody the music, all that she understands of it, she begins to sing at the same time, disorderly chorus, routine trance.

The telephone rings again, all the voices conveying the same badly feigned nonchalance. Her own cuts off.

“It’s Nicolas. Pick up?”

She hurries to the telephone, picks up. “Hello?” with a strong echo because the answering machine is still on, she looks for the stop button, feedback. Pauline yells for him to call her back, hangs up hoping he heard her. The telephone rings again, it’s him. He says, “So?”

“I was with them until six in the morning. Everything went well.”

“What went well?”

“Becoming Claudine.”

“What’s gotten into you?”

“Reflex.”

He says, plainly exasperated, “I don’t know what to say.”

“Can you come over?”

“What for?”

“We need to talk.”

“I don’t know what you’re trying to do, but I know you shouldn’t be doing it.”

“Ring quickly four times so I know it’s you?”

He agrees. As she suspected he would. As he will agree to all the rest. He’s that kind of guy, always incapable of doing the right thing, attracted to bad choices and fascinated by chaos. She understands perfectly what he’s like, what he can be used for.

She hangs up, looks at the things lying near the telephone: flyer for a special offer on delivery pizza, tube of aspirin, makeup artist’s business card, journalist’s business card, electric bill, an old Pariscope thoroughly underlined with blue and red—the things Claudine wanted to see—her phone book, a number scrawled on an empty pack of cigarettes, and a planner plastered with Post-its.

All these things, a mess from another life. Pauline feels an incredible contempt rising up in her; jumping out the window really is a fitting end for a life lived in discord. Weak bitch.

A videotape without a label, a validated train ticket for Bordeaux, an art-house cinema’s program, Pauline smiles. I really can’t imagine you going to see Swedish films, you must have had someone important to impress. A little book that cost ten bucks, keys to who knows where, a nearly empty checkbook.

She pushes the video into the VCR, hits Play. Then she takes the pack of cigarettes, dials the number, and asks for Jacques. “Hi, hello, it’s Claudine, I hope I’m not bothering you?”

On the screen a music video is playing, really young guys in suits, the famous Jacques is quite moved. “I didn’t think you would call me back. No, of course you’re not bothering me.”

Claudine appears on the screen, quick close-ups of her ass, she’s not really dancing so much as grinding like a half-wit, something that’s supposed to be sensual but there’s nothing convincing about it. She looks more like a crazy person. Terribly high heels, gold, with a strap around each ankle.

“Are you all right, my dear?”

“Yeah, I’m great, just a little drained.”

“Did you celebrate after your concert? You blew everyone away, I keep hearing people talk about it.”

He has the voice of a young guy playing at being a man. Like a protector, a cuddler. Pauline asks, “And you, your work, everything going well?” hoping that he’ll talk about himself. She has to start somewhere. On the screen, Claudine has reappeared, same outfit, but she’s on all fours, she moves her arms, probably trying to communicate I’m a cat. Pauline wonders if at some point she’ll eat pâté out of a bowl.

The famous Jacques lists the many things he has to do, as well as TV reports for cable channels she’s never heard of and a cinema dossier for a magazine that just came out.

She listens to him a bit distantly, makes little agreeable sounds, trying to get it through her skull that he’s talking to a girl that he watches on all fours, and filmed from behind doing things like pretending to be a cat, whenever he wants.

He stops listing all the things he’s working on. Pauline has a hard time understanding how anyone does so many things at the same time, and why a journalist as in demand as he must be—very, very important—is talking to Claudine like this. He asks, “And what about you, Jérôme told me there were a lot of important people at the concert. It seems they were all looking for you but you had disappeared.”

“I was tired.”

“Come on, you can’t fool me. What kind of naughty business did you get up to?”

She doesn’t respond. He doesn’t take offense, he’s all excited. “Just hearing your voice I’m hard. If you were here I’d shove it all the way up your pretty little ass.”

“I’m not alone right now. I’ll call you back.”

Claudine is on the screen again. End of the song, she throws a wink at the camera that’s supposed to be mischievous. In reality, she looks like a fat cow that would rather be grazing.

Pauline sighs. Out loud, “Cunt through and through . . . and this you don’t show me before asking me to pretend to be you. All those pigs that night thought they had seen my ass, and you didn’t think to tell me.”

She takes a blank piece of paper. Writes Jacques at the top, his phone number next to it, then writes, Journalist for all kinds of media, knows a Jérôme, up to speed about the concert, slept with.

The telephone rings again.

HE DOESN’T TAKE his eyes off Pauline. He must think that he’ll impress her with his death stare. She doesn’t react. He came to tell her that she has to abandon her plan, he had prepared an argument, but now he says nothing. That’s his problem, she senses his weakness: he second-guesses too much, leaves an opportunity for his worst emotions to surface. And she knows what’s holding him back in the first place. Because she suspects what will persuade him, she offers, “Coffee?”

And gets up to make it. He watches her, she has her back to him. She unscrews the top of the coffee maker, bangs the filter directly into the trash can to empty the old grounds, then rinses it under the water, cleaning it with her finger.

The same gestures. Which recall other mornings after all-nighters when he went there to have coffee, and the afternoons when he stopped by for a quick cup, and the starts of nights and the ends of meals. The countless times he saw her do just that. Familiar silhouette, he likes to watch it move. Intact shreds of a lost being, obsolete traces that he finds bewitching.

After that painful night, he only feels resigned. What was done doesn’t provoke any conflict in him. It immerses him in an intense calm that he never knew before, distances him and pacifies him. A dignified sadness, without severity, he no longer feels anything but the sweetness of things, he reaps only memory’s charms.

Her sister is crazy. As if she’s carrying out a ritual whose secret only she knows. She communicates her request like it’s a business transaction that would be unseemly to refuse.

“You have to listen to the messages on the answering machine. I’m not sure I completely understand, but I think they want us to make an album.”

In this type of situation, he is always bewildered not to have someone on hand who he can ask to take care of the situation for him; he feels entirely incapable. Ditch her there. Call a doctor. Slap her silly, pummel her with his fists. He settles for keeping quiet. She insists.

“Listen to them. I need you to tell me what you think.”

“Were you already sick in the head, or is it just the shock from yesterday?”

“I don’t like your sense of humor. I’d even go so far as to call it shitty. If these people are prepared to pay for it, I want to make an album with them.”

He holds his head in his hands, a funny gesture that he never does, mutters, “There’s nothing wrong with that. You have the voice for it. But you don’t have to be Claudine to do it.”

“It’ll make things easier.”

“I don’t see how.”

“I want to get it done quickly. I don’t want to meet twelve thousand people and introduce myself and be nice. Claudine knew tons of people, even if no one was interested in her they at least remember her legs. The telephone hasn’t stopped ringing since yesterday, if we do it in her name, it’ll go much faster. What I want is cash, and we have a way to get it.”

“You’re dreaming. You can’t make an album just like that, you have to—”

“I’m not dreaming at all, listen to the answering machine.”

Then, he realizes, “What did you say? We can make an album faster? You’re counting on me for—”

“Everything. I don’t want to see anyone. You do everything and you make the tracks. No offense, but it’s probably the first time in a while that you’ve had the opportunity to do something.”

“No way.”

“Listen to the answering machine.”

She plays the messages; at first he won’t listen. She fascinates him a little, her reckless courage, she scares him a little too. Obscene stubbornness, she’s a calm kind of crazy. And then the names catch his ear and he starts listening.