Читать книгу Apocalypse Baby - Виржини Депант - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNOT SO LONG AGO, I WAS STILL THIRTY. ANYTHING could happen. You just had to make the right choice at the right moment. I often changed jobs, my short-term contracts weren’t renewed, I had no time to get bored. I didn’t complain about my standard of living. I rarely lived alone. The seasons followed one another like packets of sweets: easy to swallow and differently colored. I don’t know quite when it was that life stopped smiling on me.

Today I have the same pay as ten years ago. Back then, I thought I was doing all right. Once I passed thirty, the spring went out of things, the impetus that carried me along seemed to ebb away. And I know that next time I find myself on the job market, I’ll be a mature woman, without any qualifications. That’s why I’m clinging on for dear life to the work I have now.

THIS PARTICULAR MORNING, I arrive late. Agathe, the young receptionist, taps her watch with her finger and frowns. She’s wearing fluorescent yellow tights and pink, heart-shaped earrings. Easily ten years younger than me. I ought to take no notice of her impatient little sigh when she thinks I’m taking too long to take my coat off, instead I mutter an indecipherable apology, head straight for the boss’s door, and raise my hand to knock on it. From inside his office comes the sound of hoarse screaming. I step back, alarmed. I look at Agathe questioningly, she makes a face and whispers, “It’s Madame Galtan, she was waiting for you outside, before we opened this morning. Deucené’s been getting it in the neck for twenty minutes now. Go in, go in now, it’ll calm her down.” I’m tempted to turn on my heels and rush downstairs, without a word of explanation. But I knock at the door, and they hear me.

For once, Deucené doesn’t need to glance down at the files strewn across his desk to remember my name.

“Ah, this is Lucie Toledo, you’ve already met, she was just . . .”

He doesn’t get to the end of the sentence. The client interrupts him with a shout. “So where were you, you stupid cow?”

She gives me two seconds to digest the verbal assault, then carries on, turning up the volume. “You know how much I pay you not to let her out of your sight? And then she dis-app-ears? In the metro! In the MET-RO, I don’t believe it, you managed to lose her in the metro! Then you wait half the day before leaving me a message. The school let me know before you did. That seem normal to you? Could it be you think you’ve been doing your job properly?”

This woman is possessed by the devil. I couldn’t have reacted enough in her view, she loses interest in me, and turns back on Deucené. “So why was this senseless half-wit the one you had following Valentine? You didn’t have anyone brighter on your books?”

The boss looks daunted. Up against the wall, he covers for me. “Let me assure you that Lucie is one of our best agents, she’s got plenty of experience on the ground and . . .”

“You think it’s normal to lose a girl of fifteen, on the journey she does every morning?”

I had met Jacqueline Galtan when we opened the file, ten days or so earlier. Impeccable blonde bob, stiletto heels with red soles, she was a cold woman, well-preserved for her age, very precise with her instructions. I hadn’t guessed that as soon as she was crossed, she’d develop Tourette’s syndrome. In her anger, lines start to appear on her forehead. The Botox is fighting a losing battle. A drop of white froth appears at the corner of her lips. She’s marching around the office now, her bony shoulders shaking with rage.

“So just how did you lose her, you bloody idiot, in the METRO?”

The word seems to excite her. Facing her, Deucené cowers in his chair. I feel pleasure watching him shrink back, since he never loses a chance to act like a big man in front of others. Jacqueline Galtan improvises a monologue, delivered at machine-gun speed: it’s directed at my ugly mug, my scruffy clothes, my total inability to do my job, which heaven knows is not very difficult, and the lack of intelligence that marks every damn thing I do. I concentrate on Deucené’s bald head, speckled with obscene brown spots. Short and paunchy, the boss isn’t very sure of himself, which tends to make him ruthless toward his subordinates. Right now, he’s paralyzed with panic. I push forward a chair and sit down at the side of his desk.

The client stops to draw a breath, and I seize the chance to join in the conversation.

“It happened so fast . . . I had no idea Valentine was likely to disappear. You think she’s run away?”

“Ah, how helpful, now we’re actually talking about it! It’s precisely because I’d like to know the answer that I’m paying you.”

Deucené has spread out a number of photographs and reports on his desk. Jacqueline Galtan picks up a page of a report at random, between two fingers, as if it were a dead insect, glances quickly at it, and drops it again. Her nails are impeccable too, bright red polish.

I try to justify myself. “You asked me to follow Valentine, to report on where she went. Who she met, what she was up to . . . But I wasn’t at all expecting anything would happen to her. It’s not the same kind of assignment, do you see what I mean?”

Now she bursts into tears. That’s all we needed to put us totally at ease.

“It’s just so awful, not knowing where she is.”

Deucené, looking apologetic, avoids her eyes, and stammers, “We’ll do everything we can to help you find her . . . But I’m sure the police . . .”

“The police! You think the police give a damn? All they’re interested in is getting the media involved. They just have one idea—talk to the press. You really think Valentine needs that sort of publicity? Think that’s a good way to begin her life?”

Deucené turns to me. He’d like me to invent some line of inquiry. But I was the first to be surprised that morning, when I didn’t find her sitting in the café opposite the school. The client is off again.

“Right, I’ll pay. We’ll do it my way, a special contract. Five thousand euros bonus if you bring her back in two weeks. But the other side of the bargain is, if you don’t find her, I’ll make your life a hell on earth. We have connections, and I imagine an agency like yours doesn’t want to have a lot of, let’s say, unwelcome inspections. Not to mention the bad publicity.”

As she utters the last words, she raises her eyes to look straight at Deucené, quite slowly, a very elegant movement, like in a black-and-white film. She must have been practicing that gesture all her life. She looks again at the page from the report. The files on the table are all mine. Not just the ones I put together all day and all evening yesterday, but ones they must have gone to fetch themselves from my computer. They can do what they like to someone like me: obviously they’ve been checking to see I’ve brought everything out, and haven’t forgotten or hidden anything. I spent hours selecting the most important documents and sorting them into categories, and they’ve made a total mess of it, of course everything’s out there now: from the bill at the café where I waited to the least interesting photo I took of her, even the photos where all you can see is a bit of her arm . . . It’s their way of telling me that even if I spend twenty-four hours on a dossier making sure it’s cast iron when it’s asked for, I’m deemed incapable of judging what’s important and what isn’t. Why should they be deprived of the pleasure of being sadistic to someone, when I’m right there, available, at the bottom of the food chain? She’s right to call me a half-wit, the old hag. If it makes her feel better. Yes, I’m the half-wit, who gets paid peanuts, and has just been on duty for almost two weeks trailing a nymphomaniac teenager who’s hyper-active and coked up to the eyeballs. Just for a change. I’ve been working almost two years for Reldanch, and that’s the only kind of assignment I ever get: snooping on teenagers. I was doing it as efficiently as anyone else, up to the moment Valentine disappeared.

That particular morning, yesterday, I was a few steps behind her, in the corridor of the metro. It wasn’t difficult to pass unnoticed in the crowd of commuters, because the kid hardly ever took her eyes off her iPod. As I made for the exit, an older woman, heavily built, suddenly collapsed in front of me. And my reflex was to stretch out my arms as she fell backward. Then, instead of just lowering her to the ground and hurrying on, so as not to lose my quarry, I stayed with her for a minute until some other people arrived. I’d been trailing Valentine for most of two weeks. I was sure I’d find her in the café next to this school she attended, stuffing her face with muffins and Coca-Cola, like she did every morning, with some of the other kids from the school, but sitting a little back from them, calmly keeping her distance. Except that day, Valentine disappeared. It’s always possible something has happened to her. Obviously, I wondered whether she’d spotted me and taken advantage of the accident to lose me. But I’d never felt she was suspicious. Still, after my long experience of trailing after teenagers, I’m beginning to understand what makes them tick.

Jacqueline Galtan looks down at the photos on the desk. Valentine giving a boy a blow job on a park bench, hidden from passersby by a waist-high shrub. Valentine snorting a line from her exercise book at 8:00 a.m. Valentine jumping on the back of a scooter ridden by a perfect stranger she’d stopped at a traffic light, late at night . . . I didn’t have a colleague working with me on this job. So because of budgetary constraints, I’d been teamed up with a notorious crack addict, who’d work for any rate at all, as long as he was paid in cash every night. I suppose his dealer had let him down, but anyway he’d never turned up to relieve me, and his voicemail was full, I couldn’t reach him. Nobody thought it was a matter of urgency to replace him. You had to be under the kid’s window, in case she made a run for it, and at the school gates next morning as well. In fact, it was lucky I was actually there when she disappeared. Most of the time, I had no idea what she was up to.

At the beginning of the assignment, I’d used classic tactics: I’d got another kid, who helps us out sometimes, to offer her an irresistible smartphone for a very good price, so-called “fallen off a truck.” Mostly when we’re dealing with teenagers, we just tell their parents how to fix their child’s phone. But Valentine didn’t have a cell phone, and she didn’t deign to switch on the one I’d sent her way. That didn’t help. I don’t often have to track a teenager without a good GPS installed.

The ancestor lines up the photos, looking thoughtful, then swivels her gaze onto me. “And you wrote these reports, did you?” she says quite affably, as if we’d had plenty of time to digest her tirade. I stammer out a few words, she isn’t listening. “And you took the photos too? Well, you did a good job before you screwed up.” Blowing hot and cold, the way of all manipulative people: first the insult then the compliment, and I’ll be the judge of the tone of our exchanges, thank you very much. It works too; her recriminations were so unpleasant that the compliment is like a shot of morphine on an open wound. If I dared, I’d roll over and let her scratch my stomach. She lights a cigarette. Deucené hasn’t the courage to tell her it isn’t allowed, and his eyes dart around looking for something to offer her as an ashtray.

“I assume you will take personal charge of finding her.”

Yippee, brilliant: she’s just using me as a punching bag. I wait for Deucené to tell me the name of the agent who will take over the case. I’ve never done missing persons, no experience. But he turns to me.

“You’re already familiar with the file.”

The client approves, she’s smiling again now. The boss gives me a conspiratorial wink. He looks relieved, pathetic jerk.

AN INSECT CRAWLS along the top pane of the window in the broom cupboard I have to use as an office. It has huge antennae.

I take out my card index. I don’t store much on my computer. If I’m shot dead tomorrow and they come and search through my things, and find my notes, they’ll probably think I’ve invented a system of coded language that makes Enigma look like child’s play. The truth is that when I try to read it over myself, I wonder what I meant to say. Luckily, I’ve got a good memory, and I usually end up remembering what I intended to note down, more or less. I have this set of index cards covered with weird signs, sometimes mathematical (as if I know anything about algebra).

SINCE I’VE BEEN working here, I’ve got really fed up with being assigned these teenagers. A kid can’t smoke a joint in peace without me personally being right up behind him. The first year, I never had to follow anyone under fifteen. Nowadays, it doesn’t surprise me to be asked to work in the primary-school sector. The life of their children belongs to adults of my generation, who don’t want to let their youth get away from them twice. I can’t exactly say I hate what I’m doing, but fixing little kids’ cell phones is neither glorious nor exciting. I ought to be feeling pleased at getting a bit of variety in my work, except that I haven’t the faintest idea what I should do. Deucené dismissed me from his office without asking me if I needed any help.

I try typing in Valentine Galtan’s name on the Internet. And draw a blank. No surprises there. She’s the first kid I’ve been tailing that I’ve never seen send a text message. And yet, even youngsters high on crack take the time to post a video of themselves looking totally spaced out on YouTube.

Her father, François Galtan, is a novelist. I met him briefly the day the grandmother came to hire us. He didn’t say a word throughout the conversation. His Wikipedia page is typical of those insecure people who write their own entry—any sense of decency’s gone out of the window. Who he sat next to at school, where he went to school, what books influenced him, what the weather was like the day he wrote his first poem, his super-important lectures in improbable seminars, and so on. In the photos accompanying the articles devoted to him, you can see he’s very proud of not going bald, his hair’s combed back in a great wavy mane. I suppose the first thing I should do is contact him.

Valentine’s mother abandoned the child soon after her birth. The family claims to have no idea where she could be today. I’ll have to find her, of course. The scale of the task overwhelms me. I consider resigning. But it would be better if they sacked me for incompetence, if I want to claim unemployment benefits. I’ve reached the stage of wondering whether I should look again at the TV shows about private investigators that used to make us laugh so much, to get some inspiration, when Jean-Marc knocks at my door—I know it’s him without seeing him, he bends two fingers and taps the panel gently, his way of flexing his wrist is elegant, sexy. He puts his head around the door to see if I’m alone, then goes over to the window looking on to the street. I make some coffee. He hums “J’aime tes genoux,” a Henry Salvador song, keeping time with his shoulders and hips, not bothering to take his hands out of his pockets. He’s tall, thin, but strong-looking, with a powerful frame and a way of standing up straight, occupying a lot of space. His features are irregular, he has deepset eyes, a rather thick nose, and a bulging brow. The kind of craggy face girls often like, but the ones it really turns on are his male colleagues. They think he’s a god. Jean-Marc is the only one on the team who dresses well. The rest of us look like sales reps from the suburbs. We’re not doing a job where it pays to look conspicuous. He always wears a black tie and an impeccably white shirt, and tells anyone who’ll listen that by not wearing ties, men have lost their virility. Stop wearing a suit, according to him, and you stop representing the law. He rarely visits me, unless he needs to contact some kid who might be useful to him. I have a helpful network of youngsters willing to run errands on the cheap. Today he’s come to see me because I’ve been given this difficult case. Agathe must have filled him in. From her desk, she can hear and follow everything that goes on in the boss’s office. The Reldanch Agency premises are a former blood-testing lab, and the walls haven’t been soundproofed. I’d like it if Jean-Marc were to suggest working together with me on this inquiry. But he thinks I can handle it on my own.

“Where are you going to start?”

“That’s just what I’m wondering. This kid is half-crazy. I’ve no idea what’s happened to her. And the grandmother is so scary that I can’t lean on her about it. Honestly, I don’t know. Her biological mother, I suppose.”

He looks at me without saying anything. I think he is waiting for me to outline my plan of attack.

I ask, “You’ve done missing persons, haven’t you? Aren’t you sometimes afraid you’ll find something grim?” I’m trying to sound casual, but just pronouncing these words opens up a hollow in my chest. I hadn’t realized how scared I was.

“Well, five thousand euros reward, what can I say? I don’t ask myself if I’m afraid of what I’ll find, I ask myself how I’m going to track down this kid. If you can’t see how to handle it yourself, just delegate. Everyone else does. You can share the bonus. Do you need some contacts?”

“I thought about that. I’m going to make an offer to the Hyena. She knows the ropes.”

It’s the first name that comes into my head that might impress him. I let it drop in the tone of voice of a girl who calls up the Hyena every time she loses her house keys. It’s true that I know this guy who knows her, but actually, I’ve never set eyes on her.

Jean-Marc utters a slightly choked laugh. He doesn’t look anxious and concerned anymore, he looks distant. The Hyena has a reputation. Declaring I could work with her is tantamount to saying I have clandestine activities. I’m already regretting the lie, but I go ahead with my yarn.

“I often meet people in this bar where she hangs out. The bartender’s a pal of mine, and he’s a big friend of hers.”

“So one way or another, you’ve got to know her.”

I don’t answer. Jean-Marc blows on his coffee then says, thoughtfully, “You know, Lucie, it’s just a matter of luck and perseverance. It may look impossible at first, but somehow or other a lead opens up, and then it’s just a matter of sweating it out.”

I agree, as if I could see what he means.

Jean-Marc has long been the star of our outfit, not just because he composes his reports in such a dazzling style that even when he fails on a case, by the time you reach the end you would think he had succeeded. He was the right-hand man of our old boss, and everyone thought he’d become the official number two, and go off to direct a big branch. Then Deucené was appointed director, and Jean-Marc made him ill at ease. Too tall, probably.

Jean-Marc closes the door quietly behind him. I look for the index card for Cro-Mag. I’ll call him when I go down to lunch in a while. I don’t trust the phone lines in the office, they’re all tapped, although I can’t think who’d have the time to listen to our conversations. It’s a professional reflex, I only use my phone to text birthday greetings and I avoid sending emails altogether. I know what they can cost you if there’s an inquiry or a lawsuit. And I know they can be hacked by anyone who’s nosy. I still often send letters by snail mail. To guess the contents of an envelope is a skill most agents don’t have nowadays. I’ve never had anything important to conceal, but in this job you develop a degree of paranoia.

CRO-MAG DOESN’T burst out laughing when I tell him I want to contact the Hyena. I’m grateful to him for that. He tells me to call back later. I head for Valentine’s school, to have a coffee in the bar where the kids go at lunchtime. This little private school doesn’t have a cafeteria or a playground, it wasn’t designed for the children’s needs. I don’t try to talk to them, I just eavesdrop on their conversations. Nobody mentions Valentine. They don’t know she’s missing, which means the police haven’t been called in yet. Though I’d have been willing to bet that the Galtans are well-connected enough to get the police to give this case more priority than they would for some ordinary missing person. The kids go back in to class. They’re empty headed, noisy, and over-excited. Interchangeable profiles. I’m not interested in them. It’s mutual, I haven’t registered in their field of vision. That’s my strength: I’m dispensable. I stay there most of the afternoon, reading every word of a newspaper a customer has left on a table, and ordering more coffees. Guilt at hanging about instead of starting the inquiry nags at me a bit, but not enough to prevent my enjoying the afternoon off.

ON THE PAVEMENT outside the bar where Cro-Mag works, a group of Goths are smoking, and laughing a lot, which seems contrary to their philosophy to me, but then I’m no specialist. None of them takes any notice as I push through the throng to go in.

Cro-Mag welcomes me warmly. Given his lifestyle—alcohol, hard drugs, up all night, surviving on kebabs and cigarettes—he’s looking good. He still has the kind of loopy energy most people lose after thirty, and in him it doesn’t look forced. His earlobes are deformed by the huge earrings he wears, his teeth are nicotine orange, but at least he’s got them all, that’s something. He leans across the counter to whisper that she’ll be along soon. From a distance, it must look as if I’ve come in looking for drugs and he’s telling me where to find a dealer. Scratching his chin, and tipping back his head in a virile but unattractive movement, he adds, “These days, she’s sniffing around this girl who comes in often. It wasn’t hard to get her to drop by.”

I order a beer at the bar, I’d have preferred a hot chocolate because it’s cold outside, but I’ve got a date with the Hyena and I don’t want her to think I’m a wimp. I don’t often touch alcohol in bars, it gives me a headache and I don’t like losing control. You never know what you might be capable of once you lose your inhibitions.

I’ve known Cro-Mag a long time. Over one winter, about fifteen years ago, we slept together. I’d thought him rather ugly, but after we’d had a lot to drink, he’d insisted so much that we should go home together that it was tempting. Then one day he turned up with a girlfriend in tow, from some distant province, dark-haired and pretty enough not to be ashamed to be seen with a type like him. Cro-Mag avoided me for a while after that, feeling guilty and afraid I’d ask for explanations or make a scene. But I’d stayed calm, so he’d become affectionate toward me, and could always be counted on to call and ask me to go for a coffee if he was in my neighborhood, or to invite me if he threw a party. It was via him, two years ago, that I’d heard they were looking for staff at the Reldanch Agency.

He tips out some peanuts, puts one saucer down beside me, gives me a friendly wink and goes back to filling glasses behind the bar. He’s only too willing to talk about the Hyena: he loves describing their adventures. They used to work together. They even started off in partnership. Debt collecting. Their first customer was a so-called textile merchant, in tiny premises in the twelfth arrondissement, who’d “forgotten” to pay a supplier. Their job was to suggest that he pay this long-standing bill off as soon as possible. Before they went there, the Hyena proposed to Cro-Mag that she’d be the bad cop and he could be the good cop, and he’d felt insulted. “Have you seen what I look like?” A reasonable response: Cro-Mag is built like a colossus and with his small, dark, close-set eyes, his expression veers between a scary stupidity and bestiality. Being more impressed by his mission than he wanted to admit, he’d given the guy a brutal shaking, counting on his energy to make up for his lack of experience. The guy was whining, but you could see that he was playacting just to get them to stop. The Hyena had stayed in the background, not saying a word. Then just as they were leaving, she had wheeled around, grabbed the man by the scruff of the neck, smiled, and snapped her teeth three times in his ear. “If we have to come back here, you turd, I will personally bite your cock off with my teeth, got that?”

The way Cro-Mag tells it, it was like coming into contact with the Incredible Hulk, only not green: she’d mutated into a monster, anyone would have run a mile from her. And yet afterward, she was depressed, and thought it hadn’t worked. “Couldn’t smell fear on him. Smells like fucking ammonia, it’s so gross if you smell it on someone, makes you want to hit them at once.” Cro-Mag had been even more worried than during the confrontation itself: “You’re sick,” he said, “you’re really sick.” The moment she’d grabbed the man by the neck, he’d felt as if something had splashed onto him. He called it “the urge to kill, naked, something you can’t fake.” The man had paid up that same evening. Gradually, they’d found their rhythm: he’d make the first approach, she’d go in to underline the message. A sort of alchemy surrounded them, so they made excellent persuaders. He liked to recall that it was him who’d given her the nickname: “if you’d seen her in action, in those days, you couldn’t think of anything else. A hyena; the more vicious and sadistic she was, the more she enjoyed it.” Cro-Mag was full of theories about that period in his life, and I guess he’d worked them out by talking to her. “Fear’s something animal, it’s beyond language, even if some words spark it off more than others . . . you have to feel your way, it’s like with a girl, you’re on a date but you don’t know her, you move your hands around in the dark until the precise moment when it starts to work, all you have to do then is hold it there and you can reel her in. So whether you’ve got someone who’s dumb but obstinate, or someone who’s imaginative and nervy, you have to make them get the message loud and clear: next time we’ll go for the jugular, you won’t get away, and you know that.” He’d loved working with her, he boasted about it willingly to the kids who hung around his bar as if he was giving them important lessons for life: “We made a good team, we agreed on the basics, such as: take long breaks often, the job works better if you’re feeling relaxed; always accept a bribe if it’s substantial, and, above all, when in serious danger, running away is not harmful to your health. We talked a lot about girls, too. It’s important to have interests in common. You can’t talk about the job all the time, too stressful.” And then one rainy morning, in the thirteenth arrondissement, they were going after a Russian—Russians had started arriving in Paris, this was a long time ago—and Cro-Mag had complained about his stomach ulcer. The Hyena had asked him, “Are you fed up with this job?” and it had been like a lightbulb going on: yes, he was fed up with getting up every morning not knowing whom he was going to threaten next, whether there would be many of them, whether he’d be frightened or, worst of all, whether he’d feel sorry for them and ashamed of what he was doing. He was fed up with clenching his buttocks every night when he put the key in his front door, with a hollow in his stomach at the thought of finding some men waiting for him in the living room, or his girlfriend’s body lying mutilated in the kitchen, or being pinned to the ground by a squad of cops. Yes, he was fed up with living in constant terror, without earning enough to move out of his one hundred square feet in Belleville. The only reason he was hanging on was to work with her. She had said, “If you give it up, yes, I’ll miss you. But you’re capable of doing something else. I’m not. I can’t stand being crossed. Whereas you can adapt, it’s a shame for you to wear your health out doing a job you hate.” Cro-Mag says that made him want to cry, because he realized at that moment he was going to give it up and that it was over, being a team with her. But also because he knew she was telling the truth: she was beyond saving, unfit for normal life. The difference between the truly tough and those who opt for redemption is that some people have the choice, others don’t. Every time he reached this part of their story, he got emotional, spontaneously, as if he’d abandoned an injured teammate on top of a mountain, knowing he couldn’t last long, and was now feeling guilty at being able to escape on his own two legs and get back to normal life. “The Hyena, she’s pure tragedy, when you get close to her, you really understand what it is to be lonely, sad, and unfit for the world.” When he went on like this, it was obvious that he loved her. Not “loved” as in “I want to eat your pussy,” but like when someone’s whole attitude is dear to you and every memory you share is covered with a fine golden sheen. Well. In the two years I’ve been doing my present job, I’ve had many occasions to hear things about her, and I’ve learned that she has inspired the same feelings in many people, so don’t try to tell me she suffers from loneliness . . .

They’d carried on meeting, in the usual Cro-Mag way, for a coffee from time to time. This guy must spend a crazy amount of energy keeping up with old friends. Over the years, the Hyena had become a star among private investigators: there aren’t many of those in the trade, outside crime novels. Her speciality was missing persons. Since then, the stories told about her have evolved into various, contradictory versions, some of them pure fiction. Everyone has their own tale to tell, lawyers, informers, special branch officers, the cops, other PIs, journalists, hairdressers, hotel staff, and prostitutes . . . anyone who’s involved in our little world has their own story about what she’s up to, where, how, and who with. She provides drugs for government ministries, with cover from the secret service, she recruits call girls for officials, she has ultrasecret information about ex-French Africa, she speaks Russian fluently and gets on fine with Putin, she’s on a mission to rescue hostages in Turkestan, she’s trafficking on behalf of South American countries, she’s spying on the Scientologists, she’s involved with synthetic medicines imported from Asia, the big agro-industrial firms have hired her to defend their interests, nuclear power holds no secrets for her, she’s protected by radical Islamists, she’s got a house in Switzerland, she often travels to Israel . . . But the stories all agree on one point: she’s never been sentenced in any court, because her files are too explosive for her not to be covered in any circumstances. And it’s a fact that over the past five years, when lawsuits and trials have mushroomed, no legal practice has boasted of having her as a client. She hasn’t worked for any outfit exclusively for a long time now, but her name crops up—occasioning scorn, admiration, anger, or amusement—whenever people are looking for something vaguely sensational to talk about.

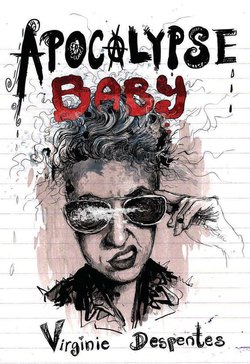

I watch the door out of the corner of my eye, with growing nervousness. I repeat over and over the sentences of introduction that I’ve prepared. I keep reassuring myself that she couldn’t have done a tenth of the things people say, and that in times of economic crisis, five thousand euros cash bonus is a sum worth discussing. At regular intervals, Cro-Mag asks me if I want anything else, I refuse, and he shuts his eyes and nods several times, a mysterious smile floating across his face, all meaning, I presume, that she’ll be along soon, you have to be patient, she’s no doubt on some top-level mission. The bar has filled up, a hoarse-voiced male singer is croaking something out of the speakers, I’ll never understand the appeal of that kind of music, you’d think you were on a construction site. Suddenly Cro-Mag’s face lights up, and the Hyena is right beside me. Very tall, hollow cheeks, Ray-Bans, men’s style, a figure-hugging white leather jacket, she must think she’s a film star. Cro-Mag points toward me, and she holds out her hand.

“Lucie? You wanted to see me?” She doesn’t take the glasses off, doesn’t smile, and doesn’t give me time to say anything. “Five minutes if you don’t mind? I’ve got to say hello to some friends, then I’ll be back.”

Seen close up, she doesn’t look at all like the mythical person I’ve heard so much about. I wait, while conscientiously sipping my half-glass of beer, clench my teeth, and tell myself that even if this is a ridiculous attempt, it won’t kill me to have made the effort.

“Shall we sit down over there? It’ll be quieter to talk.”

She goes ahead of me, confident and casual, her legs are long and slender in her tight-fitting white jeans, she’s fashionably slim, a body that tends to vanish and carries clothes well. I feel like I’m short and fat, my sweater is damp with nervous sweat, I realize my hands are shaking, and I suppose I’m lucky not to fall on my face as we go over there. She sits down facing me, arms draped over the back of her chair, legs apart, as if she’s trying to take up the maximum space with the minimum body mass. I collect my wits and wonder how to begin. She takes her shades off at last, and gives me a long cool look up and down. She has very big dark eyes and an expressive face, lined like an old Indian woman’s.

“I work for the Reldanch Agency.”

“Yeah, Cro-Mag told me.”

“I’ve sort of specialized in checking up on minors.”

“Onto a good thing there, I gather.”

“Yes, it’s one of our best lines. I’ve been tailing this girl, she’s fifteen, and I lost her, in the metro, the morning before yesterday on her way to school. She didn’t come home, she hasn’t been in touch. Her grandmother’s offered five thousand euros if we can get her back in two weeks. And . . .”

“Five thousand euros, alive or dead?”

I suppose that’s the kind of question I ought to have thought of asking.

“I hope we’ll find her alive.”

“What do you think, runaway or kidnap?”

“No idea.”

“What kind of girl?”

“Difficult, sex-mad, off the rails.”

“What’s the family like?”

“The father’s a writer, with a private income, from the family pharmaceutical company somewhere near Lyon. He brought the kid up on his own, with the grandmother being around a lot. The mother took off when Valentine was two years old, doesn’t see her, and nobody seems to know at the moment where she is.”

I open my backpack and bring out a photo of the kid. The Hyena hesitates to take it.

“I don’t really see how I can help you . . .” She glances down at the picture, and seems to think for a while as she observes it. She hesitates. I feel reassured.

“And how much will you give me if I work with you?”

“The five thousand euros bonus. It’ll be in cash. And if there’s no result . . . we’ll have to work out how to divide up my pay.”

“At that kind of rate, I wouldn’t want to put myself out too much.”

She smiles as she puts the glasses back on. I can’t tell if I amuse her or annoy her.

She has started calling me “tu” now. “So you let me keep the money, young Lucie, but are you going to work on it too, or do sweet fuck all?”

“I . . . I’d prefer to have someone working with me, in the sense that . . .”

“That you have absolutely no idea where to start. Well, at least that’s clear. Did you bring the file from when you tailed her?”

“It’s all on my laptop.”

I bend down to take it out, but she stops me with a snap of her fingers. “Can you put it on a USB?”

The Hyena has put Valentine’s photo in the middle of the table facing her. “Teenagers aren’t really my thing. They usually have good reasons to clear off, don’t they?”

“She might have been kidnapped.”

She puts her head to one side and seems lost in contemplation of the photo. She has beautiful hands, pale with long fingers, I notice that the nails are bitten down to the quick. She wears an enormous ring with a skull on it, a bit pathetic in my view, who does she think she is, the Keith Richards of the shit-stirrers? She concentrates for a moment on the portrait of Valentine, who is smiling into the camera, three-quarter angle, bright eyes, pretty dimples, glossy hair. Slightly plump. Like all girls her age, in family photos they just look like nice kids. Then the Hyena fixes her eyes on me pensively, there’s something disquieting about the insistence of her gaze.

“Little girls with puppy fat are trying to cover up for their father’s lies.”

Brilliant. I thought I was working with James Bond, and now I’m dealing with a family therapist. I don’t know how to answer in a way that doesn’t seem disagreeable, so I opt for being pragmatic.

“Teenagers go in for a lot of sugary drinks.”

“And why did the family take the step of having her watched?”

“I think they thought Valentine was . . . putting herself in danger.”

“What kind of danger?”

“You’d need to look at the other photos in the file, she . . .”

“Later. So what do they think they’re going to do, to protect her?”

“I haven’t had a chance to discuss that with them . . .”

“But all the time you’ve been doing this job, you must have some idea what the clients want, don’t you?”

“I don’t know. No. I don’t have anything to do with what they get up to, once the tailing’s over.”

“Okay. I want the five thousand euros in exchange for the kid, you can tell the clients to get it ready. And you can also tell them that there’ll be expenses. They’re rolling in it, you said?”

“Yes, but I’m in no position to bargain, because I lost sight of her . . .”

“You lost nothing of the sort. You know exactly when she went missing and where. If she decided to make a break for it, you weren’t being paid to stop her. If she was kidnapped, you weren’t being paid to act as her bodyguard, you were simply following her. What can you possibly blame yourself for? Pull yourself together, and tell her father it’s going to cost him plenty.”

“It’s the grandmother I see for everything. She’s not an easy client to deal with, very aggressive, I don’t know whether . . .”

“Perfectly normal. She wants the job done on the cheap, we’d do exactly the same in her place. But two can play at that game: just because she has a nice try doesn’t mean to say she gets away with it. Do you want me to call her for you? What’s your last name again?”

At once, I’d like to go and get myself a shovel, dig a hole in the ground, bury myself there, and let time pass. The Hyena takes out her phone, asks me for the personal number of the client. She looks as if she’s enjoying herself. I’m not, on the whole. Madame Galtan answers at once. The Hyena adopts a firm and suave voice.

“Madame Galtan? This is Louise Bizer, lawyer at the Paris Bar, I’m working with Mademoiselle Toledo, and please forgive me for troubling you so late, but we . . . Thanks for being so understanding. We have a little problem with the assignment, because Mademoiselle Toledo tells me that there has been no agreement about expenses . . . Of course, Madame Galtan, I quite see that, but you’ll understand that we can’t embark on a matter of such importance, and with such a short deadline, without running up a certain number of expenses, and it could have an unfortunate impact on the results if we had to take the metro all the time, or send you a justification ten pages long, before feeling entitled to take a plane . . . But Madame Galtan, I’m sorry to tell you that the contract you have with the Reldanch Agency doesn’t cover a missing person search . . . No, I don’t know what Monsieur Deucené saw fit to assure you, but what I have in front of me is a signed and sealed contract, which only covers a report on watching your granddaughter . . . Yes, I have been informed about the reward, and if you are aware of the standard procedures in these cases, you will know that it’s the absolute minimum for this kind of thing . . . Oh yes, I assure you. No, it’s not negligible, but it’s certainly well below the usual rate . . .”

She stands up, takes her empty glass to the counter, and signs to Cro-Mag to get her another Coke. An amused smile playing around her lips, she winks at me from a distance. The old bat must be putting up sturdy opposition, but the Hyena looks as blissful as if she’s pulling on a really good joint. After a further ten minutes’ argument, she ends the call and comes back to me looking highly pleased.

“A good sort in the end, our Jacqueline. She’s agreed, she’ll cover any expenses. And she’s given way on the ridiculous deadline of two weeks. We need to take a bit of time over this, or we’ll look like total idiots.”

“I’d never have believed she could be persuaded . . .”

“Don’t bother, the magic word was lawyer. Rich people always try to get away without shelling out, but at heart they believe you have to pay serious money, otherwise you’ll only get poor service, and vice versa. Why wasn’t it the father who asked to have the girl followed?”

“Monsieur Galtan wasn’t too keen on the idea. I gather that it’s the grandmother who’s mostly been concerned with the kid.”

“You don’t take a whole lot of interest in what you do, eh?”

“I’m not used to working on this kind of case.”

“In the future, try and listen to the client when they come to tell you about their case. For one thing it makes them trust you, if they get the impression you’re interested. But above all, if you listen properly, eight times out of ten, it’ll tell you where to start. This truth they’ve come looking for, if it didn’t hurt them so much in the first place, they wouldn’t need our services to hear it. And you’ll see, when you bring along your conclusions, even with photos under their noses, people will refuse to admit what they’re seeing.”

I can see this is going to be a whole lot of fun: If she’s going to lecture me like this the first evening, what’ll it be like in a week’s time? She takes a USB from her pocket.

“Put everything you’ve got on here, Okay? And when you’ve finished, come and find me at the counter. I need to see someone.”

I’ve had my fifteen minutes. She dumps me there and then pats my shoulder as she goes past. Looking around discreetly, I see that it’s a girl, a little brunette with short hair and thick glasses, nothing special to look at, who now has all her attention. The Hyena has her Ray-Bans back on, and she’s listening without moving a muscle. Once the memory stick is loaded up, I go over to give it to her. She barely registers me. Even through the dark glasses, you can tell she’s eating up this girl with her eyes. I thank Cro-Mag and get away as soon as I can. At the door, I turn around and see the Hyena lean slowly toward the girl, interrupting her in mid-sentence to kiss her. It’s just her head that’s moved closer to the other woman’s, her arms and hands haven’t budged. Then she returns to her initial position. She still isn’t smiling, it doesn’t seem to be part of her repertoire.