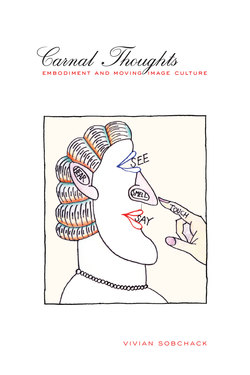

Carnal Thoughts

Реклама. ООО «ЛитРес», ИНН: 7719571260.

Оглавление

Vivian Sobchack. Carnal Thoughts

Отрывок из книги

Carnal Thoughts

Embodiment and Moving Image Culture

.....

Being a “master of the universe” presumes an existential relationship and reciprocity with space that is centered in, tethered to, and organized contiguously around one's embodied intentionality and its perceived possibility of realizing projects in the world. This is a relationship informed by the confidence that one is immanently and transcendently, as both a body and a consciousness, the constitutive source of meaningful space—that one is, indeed, the compass of the world. And space, thus constituted, is a space in which one should not be able to really get lost, a space in which one should never need guidance. This is the existential space of the young world-making child—and, in our culture, also the presumed (and assumed) existential space of the adult man. It is very rarely the space of the adult woman.

In a phenomenological description of the reciprocity between culturally informed, engendered bodies and the morphology of worldly space, philosopher Iris Marion Young has distinguished the general forms through which men and women differently perceive and live space in our culture.37 This difference is less a function of sexual difference than it is of situational difference. All human beings experience their existence as embodied and therefore immanent, that is, as materially situated in a specific “here” at a specific “now.” All human beings also experience their existence as conscious and therefore as transcendent, that is, as able to transcend their material immanence through intentional projection to a “where” and “when” they are not but might be. However, given this universal condition of human existence as both immanent and transcendent, the ratio—or rationality—of their relationship each to the other is often different for men and women in our culture. More often than men, women are the objects of gazes that locate and invite their bodies to live as merely material “things” immanently positioned in space rather than as conscious subjects with the capacity to transcend their immanence and posit space. Thus, according to Young, there is a dominant tendency for “feminine spatial existence” to be “positioned by a system of coordinates that does not have its origins in [women's] intentional capacities” (152).38 Certainly, women also exist as intentional subjects who can and do transcend their immanence, but, because of their prominent objectification, they do so ambivalently and with greater difficulty. That is, feminine spatial experience in our culture, Young suggests, exhibits “an ambiguous transcendence, an inhibited intentionality, and a discontinuous unity with its surroundings. A source of these contradictory modalities is the bodily self-reference of feminine comportment, which derives from the woman's experience of her body as a thing at the same time she experiences it as a capacity” (147). Women, therefore, tend to inhabit space tentatively, in a structure of self-contradiction that is inhibiting and self-distancing and that makes their bodies—as related to their intentionality—less a transparent capacity for action and movement than a hermeneutic problem. As a consequence, women in our culture tend not to enjoy the synthetic, transparent, and unreflective unity of immanence and transcendence that is a common experience among men.

.....