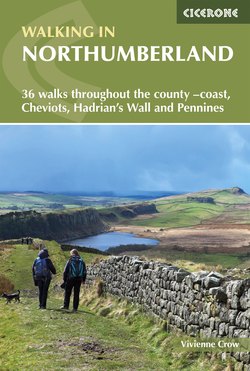

Читать книгу Walking in Northumberland - Vivienne Crow - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Northumberland – a land of open spaces and big skies

There’s something very special about walking in Northumberland. It’s got a lot to do with all the history in the landscape – from cliff-top castles and world-class Roman remains to long-abandoned prehistoric settlements hidden in the hills. It’s also got something to do with those big northern skies, largely free of pollution, unfettered by man-made constructions and opening up views that stretch on for miles and miles and miles… It’s undoubtedly got a lot to do with the landscape itself: remote hills, seemingly endless beaches, wild moors, dramatic geological features and valleys that are so mesmerizingly beautiful they defy description. It’s surely related to the wildlife, too – from the feral goats and the upland birds that are sometimes the walkers’ sole companions to the ancient woods and vast expanses of heather moorland that burst into vibrant purple bloom every summer.

Stretching from Berwick-upon-Tweed in the northeast to Haltwhistle in the southwest – two places that, even as the crow flies, are about 95km apart – Northumberland covers more than 5000km2. It’s not quite the biggest county in England, but as you wander its hills and valleys and beaches it feels like it. There are wide, open spaces here like no others found south of the border. Unsurprisingly, this is England’s most sparsely populated county – with just 62 people per km2. To put that into perspective, it compares with 73 in neighbouring Cumbria with its vast areas of uninhabited fell and moorland, or, at the other extreme, 3142 in the West Midlands and 5521 in Greater London. Want to escape from it all? This is the place to come!

Roughly 25 per cent of the county, including Hadrian’s Wall and the Cheviot Hills, is protected within the boundaries of the Northumberland National Park. The county also has two designated Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty – the Northumberland Coast and the North Pennines.

This book covers the whole county. The routes range from easy ambles on the coast and gentle woodland trails to long days out on the lonely hills: hopefully, something for all types of walker – and all types of weather.

Weather

Like the rest of the UK, Northumberland experiences plenty of meteorological variety but, being on the east side of an island dominated by moisture-laden southwesterlies, it tends to be drier and generally more benign than the western side. Having said that, the Pennines and the Cheviot Hills get more than their fair share of strong winds, heavy rain and snow. And, in winter, the easterly winds that periodically come in off the North Sea are enough to bring tears to your eyes. During summer, the coast is prone to sea fog, or haar, an annoyance that will normally burn off quickly, but can linger all day if there’s a steady wind coming off the North Sea to keep replenishing the banks of moisture.

It’s shorts weather above Rothbury!

Now for the statistics. July and August are the warmest months, with a mean daily maximum temperature of about 18°C. The coldest months are January and February with a mean daily minimum of 1.5°C. According to rainfall totals for Boulmer on the coast, the wettest period is from October to December, while April to July are the driest months. Obviously these figures will differ according to altitude, as well as latitude and longitude; and don’t forget, they’re averages.

Snow is even more widely varied from one part of the county to another – with the white stuff rarely lying for long on the coast while, in the North Pennines, it’d be an unusual winter if there weren’t occasional road closures. Generally speaking, January and February see the most, although snow can fall any time from late October to late April in the North Pennines and, to a lesser extent, in the Cheviot Hills.

The weather becomes an important consideration when heading on to the high ground, particularly in winter. Check forecasts before setting out, and prepare accordingly. The Mountain Weather Information Service (www.mwis.org.uk) covers the higher Cheviot Hills in its Southern Uplands forecast for Scotland, while the Meteorological Office (www.metoffice.gov.uk) provides detailed predictions for locations throughout the county.

Geology

Northumberland’s size gives rise to a varied and complex underlying geology. In its most simplistic form, it could be summed up as a mixture of largely Carboniferous sedimentary rocks and volcanic rocks, both intrusive and extrusive, all topped by Quaternary deposits, including those of the last glacial period.

The rolling hills of the Cheviot range are generally associated with a period of mountain building known as the Caledonian Orogeny, about 490 to 390 million years ago. The collision of several mini-continents, including Avalonia, with Laurentia and the subduction of the Iapetus Ocean, resulted in volcanic activity. This created a mass of granite surrounded by extrusive volcanic rocks, most notably andesite. The collision of the plates also resulted in faulting, evident in places such as the Harthope and Breamish valleys.

Although there are older rocks dating as far back as the Ordovician, about 450 million years ago, the rocks of the North Pennines are largely Carboniferous limestone, sandstones and shales laid down about 360–300 million years ago, when this area was covered by a tropical sea.

Hadrian’s Wall was built on the Great Whin Sill

There are certain surface features that will stand out as walkers explore the county – the andesite outcrops that form small crags on the otherwise smooth slopes of the Cheviot Hills; the fell sandstones, most prominent on the Simonside Hills; and, probably most famously, the dolerite of the Great Whin Sill, on which Hadrian’s Wall and several castles were built. The latter was formed towards the end of the Carboniferous period, when movement of tectonic plates forced magma to be squeezed sideways between beds of existing rock. The magma, as it then slowly cooled, crystallised and shrank, forming hexagonal columns.

Wildlife and habitats

With habitats covering anything from coastal dunes to 600m-plus hills, it’s not surprising that the wildlife of Northumberland is extremely diverse. While walking the coast, keep your eyes peeled for seals and even the occasional dolphin out at sea. Seals often haul out on the sands of the Lindisfarne National Nature Reserve (see Walk 4), while dolphins have frequently been spotted playing in the waters around Berwick. Seabirds such as puffins, guillemots, Arctic terns and shags nest on the rocky Farne Islands, while winter visitors to the coast include barnacle geese, brent geese, pink-footed geese, wigeon, grey plovers and bar-tailed godwits. The waders, in particular, enjoy feeding on the sand and mudflats, where they are joined by their British cousins, who abandon the hills for a winter holiday at the seaside.

Curlew in flight

At first sight, the delicate and ever-shifting dunes seem to be home to nothing more than marram grass; closer inspection reveals an array of wildflowers such as lady’s bedstraw, bloody cranesbill, houndstongue, bird’s foot trefoil and restharrow. They’re also home to common lizards and an assortment of moths and butterflies, including the dark green fritillary and grayling.

Moving inland, the uplands contain some very important ecosystems. Almost 30 per cent of England’s blanket bog is found in the North Pennines, home to peat-building sphagnum moss as well as heather, bog asphodel, bilberry, crowberry and cotton grass. Rare Arctic/alpine plants, such as cloudberry, still thrive on the highest moors. The nutrient-poor, acidic soils also support native grasses such as purple moor grass, mat-grass and wavy-hair grass, which give the Cheviot Hills, beyond the heavily managed grouse moors, their distinctive look.

The North Pennines and Cheviot Hills are important for a variety of bird species, including red grouse, some of England’s last remaining populations of elusive black grouse, and the heavily persecuted and extremely rare hen harrier, as well as merlin, kestrel, short-eared owl, peregrine falcon, ring ouzel, skylark, lapwing, golden plover, whinchat and wheatear.

As far as mammals go, the most common species you’re likely to see on the uplands is sheep, but there is wildlife too – foxes, brown hares, weasels and stoats can be seen, particularly around dusk and dawn. Small bands of feral goats also roam parts of the Cheviot Hills.

Feral goat in the Cheviot Hills

The valleys and low-lying woods are home to badgers, roe deer, voles, shrews, minks and otters. Northumberland is also one of England’s last bastions of native red squirrels, driven to extinction in other parts of the country by the introduced grey squirrel. Herons, kingfishers and dippers can often be spotted along the burns, and the woods are home to wagtails, long-tailed tits, great spotted woodpeckers, cuckoos, siskin, redpolls, finches and warblers, among others. Buzzards are probably the most common of the raptors, but any of the species found on the uplands, with the exception of the hen harrier, can also be spotted at lower altitudes.

Adders are the UK’s only poisonous snakes

Walkers should be aware that, as in most of the UK, there’s always a chance of stumbling across adders, our only venomous snake. They’re most likely to be spotted on warm days, basking out in the open – sometimes on tracks and paths. Don’t be too alarmed: the adder will usually make itself scarce as soon as it senses your approach. They bite only as a last resort – if you tread on one or try to pick one up. Even then, for most people, the worst symptoms of an adder bite are likely to be nausea and severe bruising, although medical advice should be sought immediately. It’s a different story for our canine friends: an adder bite can kill dogs.

History

People have been leaving their mark on Northumberland’s landscape for millennia. There is even evidence of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers – in the form of a dwelling at Howick (see Walk 1) and small pieces of worked flint in Allendale. But it was really only in Neolithic times that human beings, farming for the first time, began to have a more profound impact on the landscape. Suddenly, after centuries of being left to their own devices, the forests that had slowly colonised the land after the departure of the last ice sheets were under threat as trees made way for crops and livestock.

By the Bronze Age – roughly 2500BC to about 800BC – people were not only developing the first field systems seen in Britain, they were also using metallurgy to create tools and ornaments. There are Bronze Age remains scattered throughout the county, most notably burial cairns, stone circles and the prolific cup-and-ring marks found on boulders. This ‘rock art’ was made by Neolithic and early Bronze Age people between 6000 and 3500 years ago, but its meaning has been lost in the intervening centuries.

Duddo Stone Circle

Several walks in this book take in some of these important prehistoric sites, but there are others well worth visiting such as the 4200-year-old Duddo Stone Circle a few kilometres southeast of Norham, and Routin Linn, the largest decorated rock in England. A few kilometres east of the historic village of Ford, it’s covered in dozens of carvings and can’t fail to impress.

Rock art at Routin Linn

The Iron Age, starting in Britain in roughly 800BC and lasting up until the arrival of the Romans, gave us the hillforts that today dot the Cheviot Hills. These were built by the Votadini, a tribe of Celts that lived in an area of southeast Scotland and northeast England from the Firth of Forth down to the River Tyne. When the Romans arrived, the Votadini were at first ruled directly. After Hadrian’s Wall was built, and the Romans retreated south, this tribe remained allied with the invaders and formed a ‘friendly’ buffer between the legionaries and the Pictish tribes further north.

Roman ruins at Housesteads Fort (Walk 30)

The Romans left Northumberland with its most famous historic feature – Hadrian’s Wall. In AD122, while on a visit to Britain, the Emperor Hadrian ordered a defensive wall to be built against the Pictish people. Over the next six years, professional soldiers, or legionaries, built a wall almost 5m high and 80 Roman miles (73 modern miles) long, from Wallsend in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. Some of the best-preserved remaining stretches of the wall, as well as forts and other settlements associated with it, feature prominently in several walks in this book.

The departure of the Romans in the early part of the fifth century left something of a vacuum in terms of government and leadership in much of Britain. Germanic settlers, namely the Angles and Saxons, were happy to step into the breach. The first known Anglian king of the area that includes modern-day Northumberland was Ida, who ruled from about AD547. Later, his kingdom, Bernicia, united with the neighbouring Deira to form the powerful Northumbria. Now began something of a ‘golden age’ for the region: a time of peace when religion, culture, art and learning flourished. This was the time of King Oswald, the Irish monk Aidan, Lindisfarne’s Bishop Cuthbert (see Walk 4) and the great scholar Bede, all later venerated as saints. The peace was shortlived, however: in AD793 Vikings desecrated Lindisfarne in one of their first attacks on the British Isles.

Following William the Conqueror’s brutal Harrying of the North, when tens of thousands of people were killed, the Normans rebuilt several Anglian monasteries, including Lindisfarne; they established a number of new abbeys, including at Alnwick and Blanchland, and built castles at Newcastle, Warkworth, Alnwick, Bamburgh, Norham and Dunstanburgh, to name but a few.

Dunstanburgh Castle (Walk 2)

But, of course, Northumberland remained a frontier region – peace was a rare thing. Castles and territory passed from English rule to Scottish rule and back again. In 1314 Scots, led by Robert the Bruce, ransacked the north of England – towns were burned, churches destroyed and villagers slaughtered. And then there were the infamous Border Reivers, the lawless clans that went about looting and pillaging throughout the border regions. These ruthless families, owing allegiance to neither crown, brought new, bleak words such as ‘bereaved’ and ‘blackmail’ to the English language and created the need for bastles (see Walk 22), pele towers and other defensive structures. Life really only began to settle down in 1603, when James VI of Scotland became the first ruler of both England and Scotland.

Scottish forces captured Norham Catle four times (Walk 6)

Northumberland’s mineral wealth and the presence of a large port at Newcastle led to significant developments in trade and industry. Lead was mined for centuries at Allendale and Blanchland (see walks 33–36), the most prosperous period being the 18th and 19th centuries, but it was coal that really fuelled the area’s economic development. The Romans were known to use this carbon-based mineral, but it was only in the 12th and 13th centuries that the industry took off – with significant amounts of coal being exported to London via Newcastle. Come the Industrial Revolution and things really began to hot up: there were about 10,000 colliers in northeast England by 1810. With coal came the railways – some of the great pioneers of rail and steam, including George Stephenson, originated from Northumberland.

Where to stay

Tourism is an important part of Northumberland’s economy and, as such, the county is well served by accommodation providers and dining facilities. Budget travellers may want to consider youth hostels, camping or other self-catering options, although many of these close for at least part of the winter.

The best bases for walks in this book are Wooler, Rothbury, Alwinton, Seahouses, Craster, Belford, Berwick-upon-Tweed, Haltwhistle, Kielder, Blanchland and Allendale Town.

Rothbury makes a good base for several of the walks in this book

Public transport

Rural dwellers will probably regard Northumberland as being reasonably well served by public transport; but, if you live in a large city, you’re in for a shock. Most of the start points for walks in this book are served by public transport – even Alwinton and Harbottle high up in Coquetdale have regular buses. But regular doesn’t always mean frequent: if you miss your bus, don’t expect another one to come along in half an hour. In fact, if you miss the Coquetdale Circular, you might have to wait several days for the next one. Having said that, the few linear walks in the book are served by regular and reasonably frequent buses.

Two railways in the national network pass through Northumberland: the East Coast Main Line and the Tyne Valley Line. As well as serving Newcastle, some trains on the former stop at Morpeth, Alnwick and Morpeth. Tyne Valley trains between Carlisle and Newcastle stop at Haltwhistle, Hexham, Prudhoe and several other smaller towns and villages.

If you’re planning to use public transport, the best resource is Traveline – 0871 200 2233 or www.traveline.info.

Maps

The map extracts in this book are from the Ordnance Survey’s 1:50,000 Landranger series. They are meant as a guide only, and walkers are advised to purchase the relevant map(s) – and know how to navigate using them. To complete all the walks, you’ll need Landranger sheets 74, 75, 80, 81, 86 and 87. The OS 1:25,000 Explorer series provides greater detail, showing field boundaries as well as access land. Sheets OL16, OL31, OL42, OL43, 332, 340, 339 and 346 cover all the routes in this book.

Waymarking and access

Fingerposts exist even high in the Cheviot Hills

Many of the routes in this book are well signposted – even on the highest of the Cheviot Hills, you’ll come across occasional fingerposts. Some follow sections of long-distance paths, most of which have additional waymarking. The Pennine Way and Hadrian’s Wall Path, for example, are marked by the white acorn symbols of the National Trails, while paths such as St Cuthbert’s Way and St Oswald’s Way have their own signage.

As well as thousands of kilometres of bridleways and footpaths, there are huge tracts of access land where people have the right to roam without having to stick rigidly to rights of way. These are, however, subject to restrictions, including short-term closures to the general public and complete dog bans (see below).

There are tens of thousands of hectares of Forestry Commission land throughout Northumberland, as well as privately owned commercial forests, so it’s almost inevitable that, at some point, you’ll come across forestry operations involving heavy machinery. Often, walkers are simply advised to exercise caution; occasionally, paths will be diverted or whole sections of access land will be temporarily closed. In these cases, watch carefully for signs telling you what to do.

Dogs

Most of the walks in this book follow public rights of way from start to finish and, as such, there are no restrictions on dog access. However, where a route crosses access land but is not on a right of way, walkers need to check access rights. The landowner has a right to ban dogs, usually for reasons relating to grouse moorland management. Restrictions are subject to change and can be found on Natural England’s CRoW and coastal access maps at www.openaccess.naturalengland.org.uk.

People are discouraged from walking on Hadrian’s Wall, but terrier Jess thinks she’s seen a sheep

Dog owners should always be sensitive to the needs of livestock and wildlife. The law states that dogs have to be controlled so that they do not scare or disturb livestock or wildlife, including ground-nesting birds. On access land, they have to be kept on leads of no more than 2m long from 1 March to 31 July – and all year round near sheep. A dog chasing lambing sheep can cause them to abort. Remember that, as a last resort, farmers can shoot dogs to protect their livestock.

Cattle, particularly cows with calves, may very occasionally pose a risk to walkers with dogs. If you ever feel threatened by cattle, let go of your dog’s lead and let it run free.

Clothing, equipment and safety

The amount of gear you take on a walk and the clothes you wear will differ according to the length of the route, the time of year and the terrain you’re likely to encounter. Preparing for the Border Ridge and The Cheviot in the height of winter, for example, requires more thought than when setting out on a walk from Craster. As such, this section is aimed primarily at those heading out in the winter or venturing on to high ground.

Even in the height of summer, your daysack should contain wind- and waterproof gear. Most people will also carry several layers of clothing – this is more important if you are heading on to higher ground, where the weather is prone to sudden change. As far as footwear goes, some walkers like good, solid leather boots with plenty of ankle support, while others prefer something lighter.

Walkers need to be able to use a map and compass

Every walker needs to carry a map and compass – and know how to use them. Always take food and water with you – enough to sustain you during the walk, plus extra rations in case you’re out for longer than originally planned. Emergency equipment should include a whistle and a torch – the distress signal being six flashes/whistle-blasts repeated at one-minute intervals. Pack a small first aid kit, too.

Carry a fully charged mobile telephone, but use it to summon help on the hills only in a genuine emergency. If things do go badly wrong and you need help, first make sure you have a note of all the relevant details such as your location, the nature of the injury/problem, the number of people in the party and your mobile phone number. Only then should you dial 999 and ask for police, then mountain rescue.

Using this guide

The walks in this book are divided into five geographical areas: northeast Northumberland, covering the area between the Cheviot Hills and the North Sea coast; National Park (north), covering the Cheviot Hills and the area around Rothbury; Kielder, including forest walks, lakeside walks and hill walks; Tyne Valley and National Park (south), an area that takes in Hadrian’s Wall; and the North Pennines. All walks start in Northumberland, but one crosses the border into Scotland (Walk 5) and one briefly flirts with Cumbria (Walk 32).

Most of the routes are circular, but there are a few linear walks that make use of local bus services. Check timetables carefully to make sure you have enough time to complete the route.

Each walk description contains information on start/finish points, distance covered, total ascent, grade, approximate walking time, terrain, maps required, facilities (public toilets and refreshments) and transport options. The walks are graded one to five, one being the easiest. Please note that these ratings are subjective, based not just on distance and total ascent, but also the terrain encountered. Walkers are advised to read route descriptions before setting out to get a better idea of what to expect. It might be a good idea to do a relatively easy walk first and then judge the rest accordingly.

On the beach near Howick (Walk 1)