Читать книгу Military Art of People's War - Vo Nguyen Giap - Страница 8

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“In real life,” Mao Tse-tung once remarked wryly, “we cannot ask for ‘ever victorious’ generals.”1 This characteristic realism derives from decades of hard struggle, in which progress is measured not according to customary battle statistics or in terrain gained and held but in the persistence of the revolutionary forces, in their sheer capacity to survive over time. As in China, so, too, in Vietnam: the revolutionary forces have emerged the victors by showing their ability to endure protracted conflict. Vietnam has experienced nearly uninterrupted war since the mid-1940’s, and the insurgents have had an ever widening impact. Set in deeper perspective, Vietnam has fought for its independence for two thousand years. Her statesmen frequently refer to this long history of resistance warfare, and they do so for more than rhetorical effect. Out of this long history a distinctive military science has evolved, with direct relevance to the present situation.

In all their wars, the Vietnamese have confronted a more powerful enemy, whether numerically, as in the case of the ancient Chinese, or technologically, as in the case of their contemporary opponents. A strategy of passive defense, in which one relies on fortresses and treats material resources and terrain as ends in themselves, has never worked. The Vietnamese suffered their own Dien Bien Phu five and a half centuries before the French, when the impregnable stronghold of Da Bang in the interior of Thanh Hoa fell under siege by the Chinese. The common features of the successful resistance wars stand out clearly. All relied on tactical, and often strategic, flexibility. (This conception was elaborated in the first Vietnamese handbook of the military profession—in the thirteenth century!) All have utilized the natural advantages of terrain and environment to permit a mobile defense. All have utilized the expanse of time to the advantage of the resistance, building up strong forces in a war of long duration so as to be in a decisive position at the critical time. All have had a popular character, based on the support of the peasantry through a general mobilization. (A system of conscription affecting every village has existed in Vietnam from the tenth century.) Every victorious leader understood politics as the key to success.2

The inventiveness of the Vietnamese is well known. We are familiar with the use of thousands of bicycles to carry ammunition and supplies to Dien Bien Phu and with the tunnel warfare of the National Liberation Front. All this has a precedent in the Vietnamese past. In the 1780’s, Quang Trung surprised an army of two hundred thousand Chinese by raising a massive army and bringing it five hundred miles in a month and ten days. He grouped his men in threes: in the long, swift march, two men carried the third between them in hammocks. Few in the West have comprehended the significance of this tradition. From a sociological and historical point of view, the Vietnamese are uniquely equipped to understand military dynamics and to fight the present war.

The contrast with American strategists and popular thinking is stunning. As secretary of defense in 1962, Robert S. McNamara stated: “Every quantitative measurement we have shows we’re winning this war.”3 It is fruitless to speculate on the extent to which successive administrations fell victim to their own propaganda: the Pentagon appears to be incapable of understanding the dynamics of people’s war. It is not so much that McNamara’s statistics were exaggerated or even false. His military algebra is itself barren. America has been unable to endure the Vietnam war; yet this moral incapacity has never shown on the IBM punchcards. It was well understood in Hanoi long before the first GI’s mutinied at Da Nang, for the Vietnamese understanding of war goes deeper than balance sheets and kill ratios. More than this, their senior strategist approaches, in real life, the status of an ever victorious general.

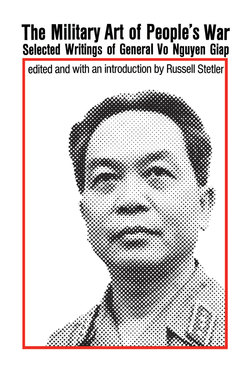

The life of Vo Nguyen Giap, taken as a whole, evinces remarkable energy and determination. Although he is less than sixty years old at the time of writing, he has helped to shape the decisive events of his nation’s history in the twentieth century. Giap was born in 1912 in An Xa village of Quang Binh province, one of the country’s poorest regions in the days of French rule. His peasant family was strongly nationalistic. Giap’s father was respected among the peasants not only for his learning but also for his participation in the last resistance to French dominion in the late 1880’s. He remained an active nationalist and sent young Giap, in 1924, to the Quoc Hoc, or Lycée National, at Hue. With its emphasis on integrating traditional (Vietnamese) and modern (Western) learning, the school was to serve as the training ground for nearly all the important figures in national politics after independence, including Ho Chi Minh and Ngo Dinh Diem. At school, Giap became acquainted with diverse currents of nationalist opinion. Records left behind by the French Surété indicate that even as a schoolboy his idealism was noted as subversive. His dynamism was equally impressive from an early age.4

As a teen-ager, Giap was dismissed from school because of his role in the growing student movement. His involvement with the underground nationalist organization, Tan Viet (Revolutionary Party for a Great Vietnam), drew the attention of the police soon thereafter. In 1930, the entire Indochinese colony was shaken by an eruption of nationalist revolts. These events stirred young Giap, who had been recalled to Hue by the Tan Viet. The Vietnam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD), a nationalist party styled after the Chinese Kuomintang, began an abortive revolt with an uprising at the Vietnamese garrison at Yen Bai, along the Chinese border, on February 9. It was crushed ruthlessly, and the VNQDD virtually ceased to exist for the next fifteen years. The fledgling Communist Party attempted to maintain the revolutionary mood. When railwaymen struck at Vinh and other workers followed suit in the Ben Thuy match factories, the communists organized solidarity actions among the peasants in the provinces of Ha Tinh and Nghe An in Annam, who had themselves felt acutely the effects of the worldwide depression on Vietnamese agriculture. Facing the swift French repression, peasant groups established rudimentary “soviets” to sustain the revolt. As six thousand peasants marched in Nghe An, young Giap in turn organized and led a student demonstration of solidarity in Hue, for which he was arrested by the French authorities for the first time. He was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment, but as the revolutionary mood seemed to wane, he was released after serving a few months.5

The Communist Party’s first years were difficult. It was founded officially in Canton in 1930, with a membership of 211, as a result of Ho Chi Minh’s negotiations with various communist groups which had come into existence from 1925 onward. Ho’s time was soon given over to other activities, and in the period which followed, the Party was directed by Tran Phu and Le Hong Phong, both of whom had been trained by the Comintern. Throughout the first decade of the Party’s existence, the influence of the Comintern (especially through the intermediary of the French Communist Party) was preponderant. In the mid-1930’s, the Party created a legal organization known as the Indochinese Democratic Front. Giap was active in the Front and probably joined the Party as a result of this association.6

In 1936 the situation was eased by the establishment of the Popular Front in France. Important cadres, such as Pham Van Dong and Tran Van Giau, were liberated from prison, and numerous restrictions on political activity were removed. The Communist Party functioned semilegally for the first time. By this time, Giap had reached Hanoi, after passing the exacting baccalauréat in Hue. He studied for one year at the Lycée Albert Sarraut before enrolling as an undergraduate in law at the university. For a time he boarded at the home of a distinguished Vietnamese writer, Professor Dang Thai Mai, whose daughter he was later to marry. He received his law degree in 1937 and pursued postgraduate studies in political economy the following year. Financial hardships obliged him to work as a history teacher during this period, and he also devoted an increasing portion of his time to political journalism. Writing in Vietnamese for Tin Tuc (The News) and Thoi The (Current Situation) and in French for Le Travail and Notre Voix, Giap soon emerged as a leading Party intellectual.7 He completed his first major work at this time, a two-volume analysis entitled The Peasant Problem, on which Truong Chinh collaborated. This work was signed under the pseudonyms Van Dinh and Qua Ninh. When the Popular Front government fell, an order was issued to confiscate and burn all copies of the book. Those which were preserved gave the guidelines for subsequent communist policy in peasant regions.8

On September 26, 1939, the Communist parties were banned in France and in the colonies. In the repression which followed, more than a thousand Party members were arrested in Vietnam alone. Many, including the secretary general, Tran Phu, were summarily shot. Giap and his young bride, Nguyen Thi Minh Giang, were in jeopardy. She and her sister, Minh Khai, were also Party members; Minh Khai had, in fact, studied in the Soviet Union and was a member of the Central Committee. The sisters fled to Vinh with Giap’s small infant. In May 1941 they were captured by the French and taken to Hanoi for trial by court martial. Both were found guilty on conspiracy charges. Minh Khai was guillotined. Minh Giang was sentenced to fifteen years at forced labor in the Maison Centrale. Her infant died, and she herself perished in prison in 1943.9

Giap himself was more fortunate, escaping to China in May 1940. The difficulty and danger of the escape, however, should not be underestimated. The Japanese had penetrated deeply into southern China in November 1939, capturing Nanning, a city only 147 miles from the Vietnamese border. Only internal political developments in Tokyo inhibited the Japanese from moving toward Indochina at that time. A Japanese strike in the six months from November to May might have sealed the border or at least increased the difficulty of exit. As it was, the train on which Giap and Pham Van Dong traveled to Kunming10 was searched several times by the French police.

Giap was soon to meet the legendary Nguyen Ai Quoc, alias Ho Chi Minh. Ho had been teaching political courses in a Kuomintang military training school during the uneasy truce between the Chinese Communists and Chiang Kai-shek. He assembled a formidable group of émigrés in Kunming, and they were to be particularly important in the organization of the Vietminh’s first military units. They lived for much of the time in the Sino-Vietnamese border regions, inhabited by the same ethnic minorities on both sides of the arbitrary demarcation. When the alliance between Mao and Chiang foundered, the Vietnamese communists were harassed by the Kuomintang and often crossed back into Indochina—only to return when the French conducted a sweep on their side of the border.11

The bulk of the Central Committee exposed itself to great danger by remaining in Vietnam throughout World War II. Truong Chinh, who replaced the executed Tran Phu as secretary general, risked his life daily by staying on in the vicinity of Hanoi. France fell in Europe in 1940, and the Vichy government soon capitulated to Japanese demands on the strategically important Indochinese colony. When the French garrison at Lang Son was relieved by the Japanese, the local montagnards of Bac Son revolted spontaneously in September 1940.12 Other nationalist uprisings of a spontaneous character followed in Do Luong and My Tho. In October, a high-level meeting was held in Kweilin to discuss the new situation in Vietnam, indicated by the arrival of some thirty-five thousand Japanese troops and by the nationalist reaction. Across the border in Bac Ninh, the Seventh Meeting of the Central Committee agreed that the Party should support the Bac Son maquis. Tran Dang Ninh, who later organized logistics at Dien Bien Phu, was sent there for this purpose. The Kuomintang, moreover, were vaguely contemplating some intervention in Indochina. Under the leadership of two Kuomintang officers, Truong Boi Cong and Ho Ngoc Lam, a small Vietnamese military force was already being organized in the town of Tsingsi, twenty miles from the Vietnamese border. The Vietnamese communists in China made contact with this group, which already included newer communist refugees in its ranks. Giap, Pham Van Dong, and other top-level cadres organized a course for some forty of the new arrivals who were working with Truong Boi Cong, in anticipation of the imminent need to return to Vietnam. To effect closer coordination between the exiles and their comrades in Vietnam, Ho returned to Vietnam for the first time in decades to preside at the Eighth Enlarged Meeting of the Central Committee, held in Pac Bo in May 1941.13

This meeting marked the re-emergence of Ho Chi Minh’s influence in the Party and of national liberation as the dominant theme in Party policy.14 It was agreed that the Party should organize a broad patriotic front, called the League for the Independence of Vietnam (or Vietminh), whose purpose would be to unite “all patriots, without distinction of wealth, age, sex, religion or political outlook, so that they may work together for the liberation of our people and the salvation of our nation.”15 The Party then decisively moved toward armed struggle. Since its formation, it had accepted armed struggle as the necessary means of liberation. This perspective was outlined as early as May 1930 in the Party’s first constitutive documents, but the first military activities awaited the decisions of 1941. Phung Chi Kien, a veteran cadre who had been trained in the Whampoa military academy and who served as head of a unit of the Chinese Red Army in Kwangsi from 1927 to 1934, was assigned the task of reorganizing the guerrillas of Bac Son into an Army of National Salvation. Half of this group was soon decimated; the remainder held on for some eight months before being obliged to disperse.16 A more successful start was made in Cao Bang, a mountainous province along the border, where the armed bands of the ethnic minorities traditionally defended local rights and autonomy. The head of an important Nung band, Chu Van Tan, traveled to Kwangsi in 1942 for discussion with the Vietminh representatives. He agreed to collaborate with the Vietminh, and Giap worked with him in Cao Bang. Both were barely thirty, but were men of exceptional ability. They worked painstakingly and with great success across a large area of northern Tonkin.17

As the Vietminh moved cautiously toward insurrection in Tonkin, many forces were at work abroad which would shape Vietnam’s destiny for more than two decades. America was already arrogating to herself the prerogative of determining Vietnam’s future. Beside her stood lesser powers who were also concerned to safeguard their interests in Indochina. Thus, political developments relating to Vietnam during the middle years of World War II were extremely complex. Allied policy-makers all attached importance to Indochina, at least in a negative sense. They saw the value of its raw materials and regarded its location as strategic, but their primary objective in the early stages of the war was to deny the Japanese access to these bases and resources rather than to attempt to seize them for Allied purposes. This was accomplished by the successes of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific.18

Political objectives were necessarily more intricate. Roosevelt was angry at the Vichy French for yielding Indochina to the Axis and at the time was unsympathetic toward de Gaulle. American policy in Asia clashed with that of the British, and de Gaulle’s close association with England caused United States policy-makers often to regard him as little more than an instrument of long-term British objectives in the Far East. Roosevelt voiced his now well-known declarations on the desirability of ending French rule in Indochina in this context.19 Reports of such declarations certainly reached the Vietminh during the war, and they were often transmitted by unsophisticated Western sympathizers of the Vietminh who embellished them or placed their own optimistic interpretations upon ambiguous phrases. Giap, Ho, and others in the leadership who understood something of the ambivalent heritage of the Western democracies, in which the ideals of liberty coexisted with racism and social injustice, studied these developments with great interest, especially in the light of the collaboration of the Anglo-American powers and the Soviets.20

The cornerstone of America’s Asian policy was Nationalist China. Washington policy-makers vainly hoped to establish Chiang’s China as a great and entirely loyal Pacific power after the war. Hence, Roosevelt’s first concrete move in regard to Indochina was his proposal at the Teheran Conference that Chiang Kai-shek should look after it following the war. Only after the generalissimo had declined such responsibility did Roosevelt put forward the idea of a trusteeship, leading to independence in thirty years, which received the endorsement of Chiang and Stalin.21 Throughout the war Chiang continued to have his own, slightly different, policy. Ironically, it was characterized by a higher degree of realism than Roosevelt’s. While he paid lip-service to all the American proposals, he pursued his own interests and objectives without hesitation. In 1942, he ordered the arrest of Ho Chi Minh, whose final release in late 1944 is generally attributed to Allied pressure. Some have argued that Chiang’s arrest of Ho resulted from his resentment of the Vietminh-OSS collaboration in the recovery of American pilots downed in Japanese-held areas. But the political motivation was surely deeper. Chiang knew of the Vietminh’s potential and was seeking to revive a Vietnamese nationalist party styled after his own. In fact, Ho’s release was made conditional on his undertaking to collaborate with the new nationalist group. All this intrigue had little effect on Vietnam’s internal development in the middle years of the war. It was not until 1945–1946 that the Chinese intervention was of substantial importance.22

The intrigues worried the French, however. The Gaullists were naturally alarmed at their exclusion from Big Power discussions on the fate of their lucrative colony. From the autumn of 1944 onward, they responded with a rash of propaganda in Foreign Affairs23 and in other scholarly journals widely read in State Department circles. There were two essential messages. The first was a catalogue of the benefits French colonialism had brought to the natives of Vietnam, in the manner of classic racist apologetics. The second was to show that Gaullist intentions for the colony’s future conformed to America’s now explicit interests and inclinations. The French were undertaking, in these unofficial policy indicators, to open the territory to broader economic penetration and to guarantee independence after a suitable period of adjustment. Unhappily for the French, a third message was often gratuitously inserted. Sensitive to the accusation that the French apparatus had willingly collaborated with the Axis, the Gaullists began to claim that this collaboration was purely tactical, dictated by the futility of resistance without American and British support in 1940. They argued that the French colons were in their hearts disposed to the Allied cause and would rise up against the Japanese at a more opportune moment in the progress of the war. If the Americans were largely unmoved by the two main points of the argument, the Japanese were profoundly impressed by the last. In consequence, they staged a lightning coup d’état on March 9, 1945, and incarcerated the main elements of the French apparatus in Vietnam.

The Japanese putsch was of singular importance: it was to provide the thoi co, or critical moment, of the Vietnamese revolution. Vietnamese strategists have always attached great importance to timing, stressing the need both to develop a long-term perspective and to recognize the crucial moment when decisive action is required. Giap’s work in the border regions had developed steadily, and by the summer of 1944 the Party was moving toward a decision to launch a general insurrection. The Central Committee met in December 1944 and outlined such a perspective. On Ho’s return from China immediately thereafter, he insisted on a more cautious approach, mainly in terms of timing. He ordered the creation of Tuyen truyen Giai phong quan (Armed Propaganda and Liberation Detachments) under Giap’s command. These detachments lay somewhere between military and political organizations. Their objectives were of both kinds: to make known the objectives of the Vietminh and to establish a secure line of communication between the highlands and the delta. The first official military unit dates from December 22, 1944. This platoon, in the Dinh Ca Valley, consisted of only thirty-four men, but it succeeded in liquidating two French garrisons along the Chinese border two days later. Ho continued to stress that the general insurrection must await that moment when conditions are ripe both nationally and internationally. The Japanese putsch produced such a conjuncture.24

The entire Indochinese situation was transformed overnight. The Japanese set out to dismantle the French administration and security structure and to establish a more reliable replacement for the duration of the war. Psychologically, the Japanese crumbled the myth of French omnipotence and invulnerability. At a more practical level, the Japanese were obliged to encourage Vietnamese participation on every level of administration and even to establish local militia forces. Japanese propaganda (under the general rubric “Asia for the Asians”) openly encouraged nationalism, and the unprecedented responsibilities delegated to the Vietnamese gave the local people confidence in their own capabilities. At the same time, Japan’s failure to accord a full measure of independence to the colony only strengthened the position of the political forces which had opposed the Axis from the start: the Vietminh.25

Outside the cities, the impact of the Japanese coup came in the rapid disintegration of the French intelligence network and the imprisonment of their security forces. These forces had been built up over many decades, and their efficiency in crushing insurrections has already been noted. When they were removed from the scene, the Japanese had no comparable network to replace them. The result was an altogether new opportunity for political and military organizing and recruitment among the Vietnamese peasantry. Vo Nguyen Giap and his comrades took full advantage of this opportunity: they were able to build an army of ten thousand men by the middle of 1945. The Japanese could not afford to send troops to attack Giap’s base areas in Tonkin. By May 1945 the seven northern-most provinces—Cao Bang, Lang Son, Ha Giang, Bac Can, Tuyen Quang, Thai Nguyen, and Bac Giang—had been liberated.26

Throughout the spring and summer, the guerrilla campaign against the Japanese mounted. In early summer, a military conference was held at Hiep Hoa. As a result of the deliberations at this conference, the Armed Propaganda Detachments merged with the National Salvation troops (born in the Bac Son guerrilla area) to form the Liberation Army. The units at its disposal were substantial. On July 17, for example, they were able to deploy a force of five hundred men against the Japanese garrison in the mountain resort of Tam Dao. Politically, the Vietminh consolidated its position throughout the country. Japanese-sponsored organizations, including militias and youth brigades, were heavily infiltrated. The Vietminh anticipated another thoi co at the moment of Japan’s surrender to the Allies and moved to be in a position to receive the Japanese surrender and fill the power vacuum. Revolutionary committees were set up everywhere to provide a de facto provisional government.27

In August the revolution was unleashed. On the fifteenth, General Giap and his troops marched into Hanoi, greeted by massive demonstrations. Between August 19 and August 25, the Vietminh moved to power from the Red River to the Mekong. On August 26, Bao Dai, descendant of the ancient emperors, head of the Japanese-approved government in Hue, abdicated in favor of the revolutionary government. At this point, the complicated positions of the Allied powers came to bear on Vietnam. No one felt the conflicting pressures so acutely as Giap. At the head of a people’s army, he knew the dynamism of the revolutionary forces. As minister of the interior in the provisional government, he had daily contact with Western diplomats and officials of every stripe, ready to impose by force what the Vietnamese would refuse to negotiate. In these crucial months, Giap’s political understanding matured swiftly.28

On August 27, the French made their awkward return to Tonkin: the new French commissioner, Jean Sainteny, arrived hastily in Hanoi by parachute. Giap led the delegation of the Liberation Committee which went to meet him. Significantly perhaps, the head of the American OSS mission, Maj. Archimedes Patti, presented Sainteny to Giap. Major Patti was regarded as sympathetic to the Vietminh, and Sainteny appears to have resented Patti’s matchmaking efforts. In this chaotic situation, the Vietminh declared their nation’s independence on September 2. Ho Chi Minh’s famous declaration began with a long quotation from the American Declaration of Independence and carried on with references to the ideals of the French Revolution of 1789. As a whole, it was calculated to appeal to the victorious Allies.29

When Ho finished, Giap spoke. Even more than Ho, in his speech Giap took account of all the conflicting forces at work and noted the latent dangers in the immediate situation. He spoke passionately of the felt desire for independence, but his words were heavy with admonitions. Giap knew that the revolution had arrived swiftly and that its organizational strength had not been adequately tested. He understood the divisions, both political and social, which might reach the surface and render the struggle more difficult in the coming period. Hence, his speech stressed unity again and again. He also emphasized the need to curtail excesses in order to foster the progress of peaceful bargaining. Turning to international questions, he stated:

As regards foreign relations, our public opinion pays very much attention to the Allied missions … at Hanoi, because everyone is anxious to know the result of the foreign negotiations of the government.

He gave no evidence of hope concerning the French. His meetings with Sainteny must have only confirmed his expectations regarding French intentions. His speech continued:

They [the French] are making preparations to land their forces in Indochina. In a word, and according to latest intelligence, France is preparing herself to reconquer our country…. The Vietnamese people will fight for independence, liberty and equality of status. If our negotiations are unsuccessful, we shall resort to arms.30

The position of the United States government was less ambiguous than the unofficial conversations of the Americans in Hanoi at that time. The senior United States official in Tonkin, Brig. Gen. Philip Gallagher, informed Washington on September 20 that Ho Chi Minh “is an old revolutionist … a product of Moscow, a communist.”31 The Allies never had the intention of permitting the Vietminh to take the Japanese surrender and receive their arms. As early as the Potsdam Conference, it was agreed that Kuomintang troops would enter the northern half of the country and British forces from the Burmese theater would supervise the surrender in the South. This arbitrary Allied demarcation at the sixteenth parallel served to reinforce the tendencies of power concentration already established by the Vietminh in the last months of Japanese rule.32

The most secure Vietminh strongholds in northern Tonkin were scarcely affected. At an official level, the Kuomintang had been effectively neutralized in Ho’s ongoing negotiations with the Vietnamese nationalists who enjoyed their backing. The Vietminh had respected the commitments entered into by Ho at the time of his release from prison and had allotted the VNQDD’s representatives more posts in the new government than their strength within the country would have commanded. At the practical level, the Kuomintang were in no position to intervene significantly with effective troops. (Although some three hundred Chinese divisions existed on paper at the end of the war, Gen. Albert Wedemeyer estimated that only five were militarily effective units—and three of these were in India under American command!) Some 185,000 Kuomintang troops are reported to have reached Vietnam, but many merely paused at the border to sell their arms to the Vietminh. Large numbers of those who entered Vietnam were actively engaged in looting; they were certainly not concerned about restoring the French presence. Those disciplined units on hand carried out their official instructions literally and saw to the rapid repatriation of the Japanese troops.33

In the South, the situation was radically different. The British had long been on record as supporting the French return to Indochina. Their command in southern Vietnam saw this as their major task and even resorted to the use of Japanese troops forcibly to depose the provisional Vietminh government. To be sure, there was resistance to the French restoration in the South, and there was vigorous fighting. But the rapid re-establishment of the French security network and the early landing of French troops made the over-all tasks of military organizing difficult. Giap continued to build his army in the North. The resulting situation prefigured the political division of the country which was to persist two decades later. French power was restored in Cochin China in a short time, and the Vietminh were left to wage a political struggle, against impossible odds, to avert a quick reconquest of the entire colony.34

While serving as interior minister, Giap carried on informal discussions throughout the autumn of 1945 with the French commissioner in Tonkin. Although Chu Van Tan held the post of defense minister, Giap retained effective control of the army, and his heavy burden of responsibility in this tense atmosphere can hardly be exaggerated. Simultaneously, he had to build an army and to keep the peace, to prepare his people for an inevitable war, and to restrain their hatred as an earnest of the new government’s capacity to govern. In January 1946 nationwide elections were organized, in which the Vietminh candidates fared well. Ho emerged as undisputed leader of the new nation. Only he received a higher percentage of the votes than Giap, who took 97 percent of the count in his home province of Nghe An. Diplomacy continued within the government, as the Vietminh maintained lingering hopes of convincing the Western powers and the coalition government in France of their capacity to govern responsibly and with moderation.35

Giap was removed as minister of the interior and was replaced by a noncommunist.36 He understood the acute crisis which was developing. On February 27, 1946, Jean Lacouture interviewed him for Paris-Saigon, and he commented thus on the progress of the talks between the Vietminh and the French:

If the conditions on which we do not compromise and which can be summarized in these two words, independence and alliance, are not accepted, if France is so shortsighted as to unleash a conflict, let it be known that we shall struggle until death, without permitting ourselves to stop for any consideration of persons, or any destruction.37

On March 2, he was named head of the Committee of National Resistance, in consideration of the increasing danger of the outbreak of war.38

The negotiations were difficult. The Vietminh were in an unfavorable position. The dikes in the Red River delta had been in disrepair for some months, and floods brought famine to Tonkin. United States bombing of the Japanese had disrupted communications between North and South, making it difficult to transport needed rice to Tonkin; over a million people were to die as a result. The famine could not be relieved without a restoration of normal relations between North and South, since Cochin China traditionally supplied its rice surplus to Tonkin. The Chinese were by then using Indochina as a pawn in a larger chess game, yielding to French demands there in return for important concessions with respect to their own territory. The Americans and the United Nations had turned a deaf ear toward Vietminh appeals for assistance and support. The Communists’ political opponents of both Left and Right accused the Vietminh of treason for consenting to talks with the French. Racial incidents erupted in Hanoi and Haiphong, the legacy of a century of racial oppression; and bitter fighting continued in the South.39

Agreement was finally reached on March 6. In a dramatic meeting in Hanoi the following afternoon, Ho and the other leaders came forward to explain why they had signed the accord. A hundred thousand people assembled. Giap spoke first, and his speech distills all the tensions then confronting Vietnam. It is remarkable for its candor:

First of all, there is the disorder of the international situation, characterized by the struggle of two world forces. One force has pushed us toward stopping the hostilities. Whether we want to or not, we must move toward the cessation of hostilities. The United States has taken the part of France, the same as England. But because we have resisted valiantly, everywhere and implacably, we have been able to conclude this preliminary agreement.

In this agreement, there are arrangements which satisfy us and others which don’t satisfy us. What satisfies us, without making us overjoyed, is that France has recognized the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as a free country. Freedom is not autonomy. It is more than autonomy, but it is not yet independence. Once freedom is attained, we shall go on until independence, until complete independence.

Free Vietnam has a government, a Parliament, finances—which amounts to saying that all the interior powers are entirely in our hands. Moreover, we have troops under us, which means that we preserve our forces and can augment them.

On the question of the unification of the three Ky, the discussions between the government and the representatives of France have been heated enough. France wants to retain Cochin China, but the government has firmly declared: if Cochin China, Annam and Tonkin are separated, we are resolved to resist to the end. In the final reckoning, the representatives of France had to yield to recognize the unification of the three Ky after a referendum of all the people of Vietnam. The result of this referendum we know in advance. Is there anyone in Vietnam who doesn’t want Annam, Cochin China and Tonkin to be a single country?

We now turn to the arrangements which do not satisfy us. First, the return of the French troops. We had to accept this provision, although it was against our hearts. We have done it nevertheless, knowing that we bore responsibility for it before our country. Why has the Government permitted the French troops to come? Above all, because if we hadn’t signed it they would have come anyway. China has signed a treaty with France permitting French troops to come to replace the Chinese troops. Moreover, France has already made numerous concessions to us. That is why we have accepted the advent of French troops. If not, there would have been no accord….

The people who are not satisfied understand independence only as a catch-word, a slogan, on paper or on one’s lips. They do not see that the country’s independence results from objective conditions and that in our struggle, to obtain it, there are moments when we must be firm and others when we must be mellow.

In the present circumstances, there were three solutions: resistance of long duration; resistance, but not of long duration; and negotiation, when the time has come to negotiate.

We have not chosen resistance of long duration because the international situation is not favorable to us. France has signed a treaty with China, America has joined the French clan. England has been with France for many months. Therefore, we are nearly isolated. If we had resisted, we would have had all the powers against us.

Then, in some places where the revolutionary movement has not penetrated deeply, many people have not taken it seriously, and if we had prolonged the resistance, there would have been a collapse of certain sectors or even loss of combative spirit. By continuing the military struggle we would have lost our forces and, little by little, our soil. We would have been able to hold only some regions. To resist in this fashion would have been very heroic, but our people would have endured terrible sufferings, for which we cannot foresee whether they would be recompensed.

From the economic point of view, from the fact that a resistance of long duration is accompanied by scorched-earth tactics, wherever we would have drawn back, it would have been necessary to destroy everything. Provisions and houses would have been turned into ashes. The whole population would have to be evacuated. Life would have become impossible. As we don’t yet have solid economic bases, a resistance of long duration would present economic dangers which would grow a little graver every day. So the Government has not chosen this way, so that the people may avoid grievous sacrifices.

If we had wished to make a resistance of some months, we would equally have succumbed, for France has every modern arm at her disposal.… So we have chosen the third way, that of negotiations.

We have elected to negotiate in order to create favorable conditions for the struggle for complete independence, to be able to await the occasion of total independence.

Negotiations have already led to the cessation of hostilities and have avoided a bloodbath. But we have above all negotiated to protect and reinforce our political, military and economic position. Our country is a free country, and all our freedoms are in our hands. We have all the power and all the time (we need) to organize our interior administration, to reinforce our military means, to develop our economy and to raise the standard of living of our people. Soon the three Ky will be reunited. The rice of Cochin China will be able to come up to Tonkin, the specter of famine will disappear.

When we consider world history, we see that numerous peoples in a bad position have been able to surmount difficulties by knowing how to wait for an occasion more favorable to their progress. Russia, for example, signed Brest-Litovsk in 1918 to stop the German invasion, in order to be able, by means of the truce, to strengthen its army and its political power. Hasn’t Russia become very strong thanks to this treaty?

The guiding idea, the goal of government is peace for progress. The way opened by the agreement is that of independence, near at hand and total, and it remains our goal.40

The French strategy is clear in retrospect. First they sought to hold on to Cochin China, where most of their investments in Indochina were concentrated in rice plantations, rubber estates, and the vast commercial network. Their promise of a referendum to determine the future status of this region was patently unenforceable. Likewise, the undertaking given in the military annex signed by Giap, Sainteny, and Gen. Raoul Salan to withdraw French troops within five years rested solely on the honor of the French. The crucial point is that the French were permitted to introduce troops into Tonkin. The Vietminh had promised to maintain order as this occurred; that is, to insure that popular resentment against the French would be restrained. On the over-all question of military forces, the agreement specified: “The whole of these forces will be placed under superior French command, assisted by Vietnamese delegates.”41

The French commander treated the delegated Vietnamese with contempt. When Giap left the first delegation to meet with Leclerc in Haiphong on March 6, the French general saw them for only five minutes and explained simply, “I would have come with or without your assent.” When Giap returned to meet Leclerc the following day, he was more than diplomatic. He introduced himself as the “first partisan of Vietnam” and called Leclerc the “first partisan of France.” He went on to speak of Paris as a capital of culture and liberty and stressed the impact of its liberation on his forces in Tonkin. Leclerc was unmoved. He emphasized that he was happy to have the cooperation of the Vietminh, that they should think of him as a friend but one who regarded himself as French before all else. When Giap left Leclerc and headed back to Hanoi by road, he was stunned by the sight of the tanks and armored cars pouring out of the LST’s onto the beaches surrounding Haiphong.42

In the days that followed Giap struggled with determination to exact as much as possible from the guarantees of the March 6 accord and its Military Annex. He asserted his right to be consulted about all French troop movements. But the Vietminh could do little more than stall for time. The French took over the functions of the Kuomintang forces in Tonkin. All the Frenchmen imprisoned by the Japanese were liberated and rearmed. The Vietminh worked hard to prevent provocative incidents which would be exploited by the French. At the same time, they prepared for the inevitable flight back to the old guerrilla bases in the hills.43

At a rally on March 22, Leclerc and Giap lay wreaths on the graves of French and Vietnamese dead and reviewed their troops together. Diplomacy and negotiation had not yet ended. On April 3, Giap and Salan signed the Convention d’État-Major, dealing with the application of the Military Annex of the March 6 accord. Points won and lost in these agreements were to matter little in the future. The political future of South Vietnam remained the crux of the issue, as it has ever since. The penultimate attempt at a negotiated settlement came at Da Lat, where Giap emerged as a brilliant politician.44

The conference opened on April 17. The French delegation was unimpressive and asserted immediately that it had no authority to discuss the question of the South. When the French denied that hostilities continued in Cochin China (claiming that there were only occasional “police operations”), Giap intervened forcefully:

To say that there are no longer hostilities in Cochin China is a defiance of truth. In fact, attacks continue everywhere in Nambo. It can certainly be said that they were launched against lawbreakers and that distinctions are difficult to make.

Thus, our elements would be assimilated into bands of lawbreakers for the sole reason that they fight in the maquis, that they possess fearless souls and shoeless feet. On this score, your FFI would also be irregulars. Radio Saigon speaks only of Vietminh troops. Our elements are Vietnamese soldiers of the Vietnamese Army…. We shall never give up our arms…. We want peace, yes, but peace in liberty and fairness, a peace which conforms to the spirit of the March 6 convention, and not peace in resignation, dishonor and servitude….

Our position is clear. A month and a half after the March 6 convention, we demand that hostilities cease against our troops in Nambo, with preservation on both sides of their respective positions. We demand that an armistice commission be established in Saigon, for this tragic ignominy must cease….

The talks soon deadlocked on the precise nature of the federal assembly to be established for the new Indochinese Federation. On the key question of the future of Cochin China, the French would only equivocate. Giap argued tirelessly, and on June 25 Le Monde described him as “a political man in every sense of the word.” When the conference ended, Giap wept. He knew that there would be no peace.45

In late May, President Ho departed for Fontainebleau for further talks with the French. These negotiations dragged on through the summer, and the stratum from which the French delegation was drawn made clear that they attached little importance to the conference. In Vietnam, Giap was a de facto head of state. As chairman of the Supreme Council for National Defense, he worked to strengthen and consolidate the Vietminh position. A modus vivendi was reached at Fontainebleau in September, but by then no one seriously regarded it as functional. It was only a matter of weeks before the first Indochinese war had officially begun.46

Henceforth, Vo Nguyen Giap was to be known to the world not as a diplomat, but as commander in chief of the Vietnam People’s Army. As such, his day-to-day life is much less a matter of public record. Few foreign journalists have had an opportunity to see him, and there are few personal accounts of the historic moments in which he has participated directly. Even the history of the Indochinese war has not been recorded in detail from the Vietminh side. The early period is especially obscure. These were the difficult months in which the Vietminh had to build its bases in Tonkin and begin to send organized units southward. Giap’s own work was not merely practical; building an army also entailed developing an understanding of the war and an analysis of the struggle to be waged. In 1947 he published, in a limited Vietnamese edition, a work entitled Liberation Army, which was to serve as a key text for military cadres.47 The People’s Army built up regular units gradually. Its structure was a pyramid. The base was the peasant masses, who created their own local defense forces. From these, guerrilla and mobile forces could be organized. The process of selection carried on to the point of recruitment of regular forces from the most seasoned units. An army structured in this way could not be destroyed. The regular units were constantly replenished from below with combat veterans. In 1950 the Vietminh had built up its forces to the point of organizing its first regular divisions. By 1951—in two years—the People’s Army had increased the strength of its regular forces four-fold.48

The broad contours of the war are indicated by General Giap in the writings that follow. These articles, interviews, and speeches represent the most complete body of analytical writings on the two Indochinese wars written from the point of view of the insurgent forces. The lessons of failed negotiations and broken promises which we have narrated in this introduction are reflected in the principles expounded in these writings. When the Vietnamese entered their second round of negotiations with the French in 1954, they did so from a position of incomparably greater strength, dramatically highlighted by the Dien Bien Phu victory. Yet in many ways, the Geneva settlement was flawed in similar ways to the 1946 accords. The concessions made by the West were again unenforceable. As commander of the People’s Army, General Giap was to appeal repeatedly to the International Control Commission established at Geneva to demand the enforcement of the agreement’s provisions and to protest at violations of the agreement by the Diem regime. When conditions grew worse in the South and the revolt against Diem brought into existence a new organ of struggle—the National Liberation Front, in December 1960—the task fell to Giap to explain the new circumstances to the ICC. In a historic letter of January 26, 1961, to Ambassador M. Gopala Menon, chairman of the ICC, Giap wrote that “violence and oppression have led them [the southern people] into a situation wherein they have no way out other than to take in to their own hands the defense of their lives, property and living conditions.”49

The second Indochinese war was set in a new global context, in the wake of successful revolutions in Cuba and Algeria and at a time of ferment throughout the Third World. Giap’s later writings take full account of these developments and are imbued with a deep internationalism. Eighteen months before Che Guevara called for “many Vietnams,” Giap considered how “many Santo Domingos” would sharpen the contradictions in which imperialism is fixed.50 But internationalism has never blurred Giap’s respect for the sovereignty and independence of nations in the struggle for socialism.51 His determination is strong, and he knows that his country cannot be independent until the last foreign soldier is gone. We hope that the writings presented here will help the reader understand this determination and gain some insight into the strategy which has led Vietnam to its victory over the United States. We also hope that these writings will constitute the final chapter in Vietnam’s two-thousand-year saga of war and injustice, and we trust that the 1970’s will begin a new period of liberation.

Russell Stetler

London

November 1969

Notes

1. Quoted in J. S. Girling, People’s War: The Conditions and the Consequences in China and in South-East Asia (London, 1969), p. 58.

2. The best analysis of the impact of Vietnamese military history on present-day strategy is that of Georges Boudarel, “Essai sur la pensée militaire vietnamienne” in L’Homme et la Société, n. 7 (January-February-March, 1968). Though marred by small inaccuracies, this article is a first-rate contribution.

3. Quoted in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House (Boston, 1965), p. 549.

4. Source material on the life of Vo Nguyen Giap is scant, and most of the Western accounts are unreliable. We have, therefore, relied wherever possible on conversations and interviews with Vietnamese friends who are personally acquainted with General Giap. He has contributed two brief memoirs himself, but these deal only with a limited period of his life. One is included as the first chapter of this volume, and the other appears in two slightly different versions as “Stemming from the People” in A Heroic People (Hanoi, Foreign Languages Publishing House, n.d.) and as “Naissance d’une armée” in Récits de la résistance vietnamienne (Paris, Maspero, 1966). We shall cite below the standard Western texts which we have consulted. For a discussion of Giap’s family and early life, for example, see Bernard Fall, “Vo Nguyen Giap: Man and Myth” in People’s War, People’s Army (New York, Praeger, 1962), pp. xxix–xxx; Philippe Devillers, L’Histoire du Vietnam de 1940 à 1952 (Paris, 1952), p. 70; and Robert J. O’Neill, General Giap, Politician and Strategist (Melbourne, 1969), pp. 1–4.

5. See Fall, op. cit., p. xxx; O’Neill, op. cit., pp. 5–10; and Jean Chesneaux, “The Historical Background of Vietnamese Communism” in Government and Opposition, v. 4, n. 1 (winter 1969), p. 121.

6. Chesneaux, op. cit., p. 119, and The Vietnamese Nation: Contribution to a History (Sydney, 1966), p. 144; Devillers, loc. cit.; and Fall, op. cit., p. xxxi.

7. Fall, op. cit., pp. xxxi-xxxii, and O’Neill, op. cit., pp. 10–11.

8. Wilfred G. Burchett, Vietnam Will Win (New York, 1968), p. 161.

9. Devillers, op. cit., pp. 72–73 and 264.

10. O’Neill, op. cit., pp. 16–17.

11. See Jean Lacouture, Ho Chi Minh (London, 1968), pp. 55–56, 60–61.

12. Boudarel, op. cit., p. 188.

13. Ibid.; Lacouture, op. cit., pp. 57–58; O’Neill, op. cit., pp. 21–24; Hoang Quoc Viet, “Peuple Héroïque” in Vo Nguyen Giap et al., Récits, pp. 162–165; and Ellen J. Hammer, The Struggle for Indochina, 1940–1955 (Stanford, 1966), pp. 95–96.

14. Chesneaux, “Historical Background,” p. 119.

15. Lacouture, op. cit., p. 55.

16. Boudarel, op. cit., p. 188.

17. Devillers, op. cit., pp. 102, 105.

18. See Gabriel Kolko, The Politics of War: The World and United States Foreign Policy 1943–1945 (New York, 1968), chapters 4, 9, and 24 (especially, pp. 607–610).

19. Ibid.

20. French journalists and historians writing during the war (including Devillers, Fall, and Lacouture) shared the view that the OSS was entirely anti-French and, by implication, an agent of the Vietminh. This view is also to be found in standard American works which rely heavily on French sources (e.g., Hammer, op. cit.). It is, therefore, hardly surprising that the Vietminh should have been confused about American intentions.

21. Kolko, loc. cit.

22. See chapter six of Hammer, op. cit.

23. For example, Gaston Rueff, “The Future of French Indochina,” Foreign Affairs, v. 23, n. 1 (October 1944).

24. Boudarel, op. cit., pp. 188–189; Fall, op. cit., pp. xxxiv–xxxv; Hammer, op. cit., pp. 99–102.

25. Hammer, op. cit., pp. 101–103.

26. Ibid., p. 100.

27. Boudarel, op. cit., pp. 188–189; Fall, op. cit., pp. xxxiv–xxxv; Hammer, op. cit., pp. 102–105.

28. Truong Chinh, The August Revolution (Hanoi, 1947); Boudarel, op. cit., pp. 188–189; Devillers, op. cit., p. 151; Hammer, op. cit., 102–105.

29. Hammer, op. cit., pp. 105, 128–131; Devillers, op. cit., p. 182.

30. Devillers, op. cit., p. 182; Hammer, op. cit., p. 131. Giap’s remarks are quoted in Hammer, from D.R.V., Documents, n. d.

31. Cited by Kolko, op. cit., p. 610.

32. Ibid., pp. 609–610.

33. Ibid., p. 202; Hammer, op. cit., chapter six.

34. Hammer, op. cit., chapter five.

35. Devillers, op. cit., p. 201.

36. Hammer, op. cit., p. 144.

37. Cited in Devillers, op. cit., p. 221.

38. Hammer, op. cit., p. 144; Devillers, op. cit., p. 220.

39. Hammer, op. cit., pp. 144–156; Girling, op. cit., p. 120.

40. Quoted in Devillers, op. cit., pp. 228–230, as translated from the Vietnamese version from Quyet Chien, Hue, March 8, 1946.

41. Girling, op. cit., p. 17; Hammer, op. cit., pp. 148–156; Devillers, op. cit., p. 225.

42. Devillers, op. cit., pp. 234–235.

43. Ibid., pp. 236–237.

44. Ibid., p. 250; Hammer, op. cit., p. 159.

45. Hammer, op. cit., pp. 159–165; Devillers, op. cit., pp. 256–257.

46. Hammer, op. cit., pp. 165–174 and chapter seven; Devillers, op. cit., pp. 256–257; Fall, op. cit., p. xxxvi.

47. Burchett, op. cit., p. 163 et seq.; Hammer, op. cit., p. 232.

48. George K. Tanham, Communist Revolutionary Warfare: The Vietminh in Indochina (New York, 1961), p. 102; Girling, op. cit., pp. 131–135.

49. Vo Nguyen Giap, We Open the File (Hanoi, 1961), p. 16.

50. See “The Liberation War in South Vietnam,” below.

51. On the occasion of the Prague Army Day celebration in the autumn of 1968, Giap personally cabled his Czech counterpart, General Martin Dzur, urging him to consolidate the national defense and defend the gains of socialist construction of the Czech people by strengthening the army. See Reuters dispatch, Hong Kong, October 5, 1968, quoting Vietnam News Agency.