Читать книгу One Night in Copan: Chronicles of Madness Foretold Tales of Mystery, Fantasy and Horror - W. E. Gutman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIN Dranomos

A desert is a place without expectations.

Nadine Gordimer

It began with the birds. Dead birds. Dead grackle chicks. Had they tumbled out of their nest? Were they ousted by greedy siblings, dislodged by marauding ravens and beaked to death? Was it Shadow, the itinerant tomcat, the elusive feral feline that kept tongues wagging well after backyard gossip had turned to very small talk? The grackles’ eye sockets had been picked clean, their belly feathers plucked as if in haste, their slender legs broken at the knees. They lay there on the concrete patio, four of them, disfigured, stilled, frozen in time.

Then there was the dead lizard at the bottom of the pool, a ten-inch striped little beauty with long, willowy digits and an endearing expression. I’d used a fine-mesh net at the end of a long pole to bring it to the surface, and I’d examined it for signs of life. There were none. The graceful reptile’s eyes were shut. Saddened, I’d cupped it in my hand for a while. Sadness turned to unease. I buried it in the shade of a honeysuckle bush.

No, it wasn’t superstition, legend or a penchant for mysticism that triggered the disquiet, the premonitions. Many years earlier I’d come upon a dying seagull, a stately old bird that flapped its wings listlessly, its lifeless eyes turned skyward as it gasped for one last breath of sea air. The sight of the expiring ace flier had filled me with sorrow; it also produced a numbing fear I’d never known. I remember getting chills, feeling the hair on the back of my neck bristle as if caressed by a sudden, icy gust.

Six months later, my mother died of pancreatic cancer. It’d taken months of pain -- constant, searching, tenacious. She’d turned yellow, gone bald, shed half her weight and slowly lost her mind. I’d witnessed this irreversible transformation with disbelief, helplessness, anger. Our evasions and lies had kept her hoping, fighting at first. Then she’d given up. One day, when the others left the room to stretch their legs after an all-night vigil, I’d touched her face and called her name.

“Mama, mama, don’t go.”

She’d winced and her eyelids had parted ever so briefly, revealing cloudy, swollen, lifeless orbs, like those of the moribund seagull. I knew she’d seen me, felt my presence, heard the words I’d whispered. She expired that evening. June was young and the air was filled with spring’s heady bouquet. A seagull flew by. Every vestige of childhood in me died with my mother that day. Only the dreams she’d dreamed for me survived, some as yet unfulfilled, others beyond reach except in the limitless regions of a mother’s love.

I’d cursed her. No one understood the rage that surged within me. I felt betrayed, lost, abandoned. Taken for granted, often unnoticed in life, longed for in death, my mother would have been the first to grasp this paradox. No one else did, not even my father who, familiar with the contradictions of the human soul, had failed to recognize in his son’s calumnies the brittle fragments of a broken heart. Heeding her last wishes, we’d buried her ashes in a family plot where grandma Henrietta and Uncle Johnny would later be laid to rest. It’d rained that day; it would rain every time I came to the cemetery. And I’d grumbled because my shoes had gotten wet and caked with mud. It’s the nature of coincidence to deliver a hint of irony.

All during my mother’s ordeal, and after her death I’d harked back to that fateful winter morning stroll on the beach when the majestic sea bird had expired at my feet. The sight of dead animals, road kill, but especially birds, would forever elicit surges of melancholy and angst. The grief I felt had not a trace of spirituality. What I sensed was visceral, dark, menacing.

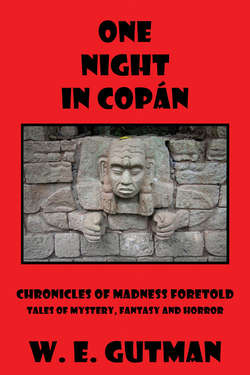

Many years later, as I went on assignment to Central America, the sight of dead birds would take on a new aura. Alive, birds symbolize freedom from earthly bounds. Dead, especially when placed on someone’s doorstep, they telegraph a warning, the threat of a looming calamity. Several investigative reports I’d written had earned me ill-omened accolades: a dead pigeon whose unfurled wings had been stapled to a small funeral wreath and propped against my hotel room door at the Casa Grande in Guatemala City; two dead sparrows similarly positioned on the stoop of my rented studio in Copán. I’d somehow managed to keep one step ahead of my would-be assassins but I would never look at dead birds the same way again.

It was not surprising that the sight of the mutilated baby grackles, less than a week after I’d moved to Dranomos, would stir feelings of anxiety. I’d come down from the small cloud-shrouded mountain town of Patchahei to the high desert plateau where the sky is almost always blue and the sun percolates for months on end. Long, bitter snowy days and frigid nights at 4,000 feet had taken their toll and the prospect of gentler winters and warmer summers had beckoned me down from the summit. Little did I know.

Then, one day, I heard it: a whisper, a distant murmur; throaty at first then high-pitched as it subsided, like the sigh of a mortally wounded beast or the wail of a restless spirit. I couldn’t tell where it was coming from. It ebbed and flowed like the tide, like an intermittent rustling of leaves. Like a draft squeezing through some narrow aperture.

A more thorough search for the source of these gloomy squalls took me to the laundry room, a small area with a door leading to the garage. To my relief, it was only the wind insinuating itself under the garage door and whistling with every gust.

I also thought I’d heard, merging with the reedy crescendo and ebbing of moans and whimpers, what sounded like laughter -- no, not the resonance of gaiety or merriment, not the giggle of children or the chortle of men telling salty jokes. What reached my ears, I thought, was a sequence of long sepulchral wails, otherworldly, warped by the newness of my circumstance in this austere, taciturn expanse of rock, sand, stunted Joshua trees, clumps of sagebrush and roving tumbleweed.

I’d spent the winter settling in, arraying the furniture, lining my favorite books on the shelves, placing bric-a-brac and curios on the mantelpiece and other outcroppings, adorning the walls with the pictures I’d painted and the lithographs I’d collected over the years. A happy loner too busy to be bored, I’d put off any interaction with my neighbors, few as they were, until spring. Now and then I’d spotted a couple of lonely figures dashing in and out of their houses, scurrying across my field of view as if they were being pursued by some menacing presence. It’s not that I’d waited for the Welcome Wagon or a neighborly invitation to a family brunch. I could dispense with these niceties. I considered them pointless, synthetic and somewhat intrusive. It’s just that I’d found it odd that my presence in this gated hamlet, this remote, desolate mesa ringed by barren, cratered hills had been largely unnoticed, if not ignored. So I’d happily gone back to work on what would perhaps be my magnum opus, my one-way ticket to the blue Mediterranean, the deliverance that penury and anonymity had so far denied me.

“We had our first snowfall,” I wrote in my journal. Bad choice of a pronoun, I’d exclaimed. We? This is not an editorial position. I rewrote the sentence:

“It snowed last night. The mountain tops are peppered with white. A thick, ground-hugging fog is slowly chewing up the scenery. It’s time for the Wellbutrin and a change in screensavers -- from the red and gold of a New England autumn to a sun-drenched islet set like an emerald on a turquoise sea and ringed with white sandy beaches and dotted with tall coconut trees swaying in the breeze. It’s time to let my mind roam. It’s time to hunker down, brave -- no, endure -- winter and watch for the first signs of spring.

I was what the gallant French refer to as “entre deux âges,” [middle-aged] and blunter Americans obliquely describe as “well past his prime”: an old man who’d managed to ward off the ravages of time and the onset of decrepitude by keeping busy, stretching time.

Time is not a renewable resource. What cannot be prevented or changed must be weathered.

I’d always thought that every man has a “tale” locked up within him that, as it unfolds, struggles to emerge. “Every life is a best-seller.” I’d come up with this aphorism when I lived in Queens, New York on the 14th floor of a 16-story building. At night, across the playground, a building of equal stature revealed through dozens of lit windows a patchwork quilt of silent dramas, each circumscribed by time and space. The diminutive creatures in my field of view, I’d suddenly realized one evening, some unwinding in their living rooms, others readying for bed, others yet quarrelling or fixing dinner in closet-sized “galley” kitchens, each acting out a preordained scenario, must surely have a compelling story to tell that will never be told. I remembered feeling empathy for the strangers I spied upon in moments of introspection, each framed in his own shadow box, each engaged in life’s mind-numbing, often absurd pantomime.

I’d learned a great deal about dignity and vulgarity, refinement and boorishness, solitude, boredom and carousing, and I’d realized that I too, at some time or other, must have been the object of someone’s absent or amused scrutiny.

It had all happened so fast. I’d taken early retirement, left genteel Connecticut and set out on a five-day, 3,000-mile drive across America. Its vastness and awesome beauty had filled me with exhilaration and appeased for a while the emptiness within. The emptiness returned when I reached the desert. Behind me was the narrowing perspective of an arrow-straight road merging into the horizon line. Ahead lay a barren, petrified expanse. Alone in its vast, sallow bosom, overwhelmed by the immensity and desolation around me, I stopped, got out of the car and looked at the limitless blue vault above, dotted with strange cloud formations, some the shape of flying saucers, others wispy and elongated like lines of cocaine, others yet splaying like supernovas or metastasizing cells. I surveyed the tawny parched earth at my feet. Everywhere, clumps of sparse, stunted shrubs and contorted Joshua trees clung stubbornly to life in this lifeless citadel. I felt lost. I wanted to scream. The scream died in my throat as I set my eyes on a lone yellow poppy, its dainty orange petals quivering in the breeze. Memories cascaded through my mind. I remembered the wild blood-red poppy fields of Abu Gosh, outside Jerusalem, where I’d gamboled as a boy, taking in their heady aroma, napping under a blanket of undulating blood-red blossoms and dreaming Technicolor dreams. I remembered the wistful French love song of my youth, “Comme un petit coquelicot,” [Like a little poppy]. I’d been swept in a vortex of indescribable emotions every time I heard it. Poppies are still my favorite flowers. And I remembered Paris, the city of my birth. Words, images, colors and aromas danced inside my head, faint, disjointed, stranded at the limits of consciousness. I felt my tongue forming silent thoughts, like prayers or mantras. Emboldened by self-discovery, delivered from their cerebral bonds, the words gushed forth. It was a soliloquy of stupefying candor and sorrow, part confession, part supplication, words driven by longing, by despair, by a fear of madness, words one only dares to utter in the desert’s deafening silence. I looked at the sky. Then I looked at the poppy and the babble ceased. It had wilted in my hand. But its subtle, intoxicating scent still lingered on the tip of my fingers, in my nose, on my lips.

“I should have never plucked it. I should have never set eyes upon it,” I heard myself wailing as my eyes now strained against the milky glare of day.

Somewhere at the edge of a gray town, a cookie-cutter copy of a thousand gray tank towns, on a gray street senselessly named after some tree or flower, deep inside a gray room adorned with mementos and frozen glimpses of time misspent, the self-probing continues. I’m not in Paris or in New York but in a grim, far-flung gray tank town in the middle of nowhere. I’m out of range of the ultimate cause so I seek answers in the gray dancing shadows on the ceiling and hang on to rapidly dissolving shreds of graying memory.

America. Fifty-six years spent chasing after the same dream, lurching from a brief state of wonderment to one of frustration, disillusionment and anger as I stumbled on the desiccated fragments of discredited myths and embalmed fiction, trying to fit in, hopelessly out of step, out of tune. Yes, I’m a restive stranger, an untamed renegade, ill at ease in my own skin, an interloper in a realm I do not fully fit in, outwardly housebroken, inwardly raging and defiant and aching, treading unfamiliar waters, lost in the blinding light of day. Fifty-six years: Two billion heartbeats pumping life into an out-of-soul experience, each pulse adding to my estrangement and perplexity.

The poppies are now in bloom. I scan the high desert mountains that surround me, dwarf me, fence me in and deny me the privilege of a horizon line where freedom looms.

Somewhere in the distance, a car rumbles by like a great booming wall of sound.

In Dranomos, I’d quickly learned, neighbors had no tales to tell. Ghostly, furtive, aloof, poker-faced, they seemed to live like me -- hermits in a wasteland of topographic banality and cultural sterility, un-ordained monks who live in self-created cloisters where time, frigid winters and long periods of lung-searing heat and drought mummify the body and scorch the soul.

It would be a while before the doves began cooing at the advent of spring but by then I knew that the wind, the heat, the unbearable sameness of it all had rendered everyone insane and that I would escape a similar fate only by fleeing from this morose, howling desert. What I hadn’t reckoned yet was whether I’d make my getaway trussed in a straightjacket, screaming as the wind added its voice to the sinister chorus of evil laughter, or carted away on a gurney inside a body bag.

Last week two lizards and two field mice drowned in the pool.

Yesterday, I retrieved a dead bat.

On cloudless days, as the sun begins its slow westward descent, an inscription -- a name -- materializes, as if fashioned by some spectral hand, at the bottom of the pool. It reads HILLARY AN. I would later learn that Hillary An, a former tenant, had drowned in the pool. Some say it was suicide. The wind, they surmise, had driven her mad.

Early this morning, my old friend Guy died of leukemia. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered, as he had instructed, from the top of a mountain where eagles nest. Guy thought birds are the reincarnated souls of men freed from their earthly shackles.

I turn my gaze heavenward at a searing, implacable sun. Then I look at my shoes, caked with brown desert dust. I remember the damp slippery clay by my mother’s grave.