Читать книгу The Inventor - W. E. Gutman - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Michel Montvert loves books. He was six or seven when he first leafed through an art album he had casually pulled off a shelf at home. With the old Blaupunkt radio humming in the background, he sat crossed-legged on a fading Persian rug, the large tome stretching across his lap. He would forever be transformed by the experience.

“They were all there,” Montvert told me years later as we dined at Jo Goldenberg’s on Rue des Rosiers in Paris. “Titian. Botticelli. Michelangelo. Rembrandt. Van Eyck. Van Gogh. Corot. Gainsborough. Turner. Toulouse-Lautrec. Utrillo. Gauguin. Degas. Renoir. Monet. Cézanne. I couldn’t get enough. I was seduced by the interplay of light and color, awed by motion so deftly captured and frozen in space, inveigled by the lyricism and gauzy quality of impressionism, the precision of neo-Classicism, the refinement of the Venetian School, the probing intensity of portraiture.”

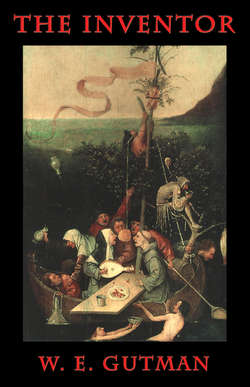

There was one artist he kept revisiting, and one painting in particular among several strange works by an old master whose name meant nothing to Montvert at the time. Nor did the mysterious and exotic title of a legendary masterwork he found himself staring at and dissecting inch by inch for hours on end.

“I was only a kid but I sensed that, unlike the other painters, this artist didn’t just replicate life. He imagined it, fabricated it, refashioned it, upended it,” Montvert had exclaimed, glints of childlike wonderment flickering in his eyes.

“Set against gossamer landscapes and improbable perspectives, his images seem to jump out of their two-dimensional plane, splashing the optic nerve with exquisite melancholy, dotting his universe with things and creatures that nature, in its infinite wisdom, or utter lack of imagination, has chosen not to sire. Here you find monsters and mutants and grotesque hybrids. There you come face to face with warlocks and grimacing witches frolicking among aimless throngs given to paroxysms of elation or stricken with catatonic stupor. Encoded in the language of allegory and symbolism but crafted to bare enduring truths, his paintings said more than they implied. They seemed to be speaking to me with an intimacy that was both comforting and terrifying. I let my eyes be seduced and my eyes wandered, seeking to be challenged as they were being dazzled. In a way I could not fully process at the time, I was also stirred by their eroticism, which I found more beguiling than the prosaic photos I sneaked a peek at in my father’s medical books.”

What Montvert finally grasped when, as an art student, he rediscovered his childhood idol, was that in his company he had been treated all along to a vivid and eloquent articulation of the idiom of conflict.

“The seemingly mismatched details he crams into his paintings are like pieces of a puzzle,” he explained. “You can ponder each one individually and miss the big picture, or you can bring them together into a congruent whole that delivers the artist’s central message: Life is a journey across a minefield of ceaseless friction. Resentment spawns hostility. Envy elicits malice. Ignorance leads to rigid thinking. Fixed ideas breed suspicion. Greed, narcissism, scorching ambition and uncontrollable lust inspire violence.”

Conflict is not only elemental; it is essential to life. Evolution of the species is driven by conflict and sustained by adaptation to the stresses it creates and the torments it inflicts. The clash of egos, the spark that ignites passions and deepens the ideological divide between men, leads to a more sinister form of conflict because the irreconcilable beliefs, opinions and value systems that trigger hostility are imparted, not inborn. It was Sigmund Freud who postulated the now widely accepted theory that we are the product of our subconscious. Freud was careful to add that the subconscious is neither amorphous nor indelible, but rather the aggregate of myriad post-natal influences and coercions. The psyche is fashioned, transformed and often fouled by early childhood experiences and warped by brainwashing -- the planting of preset ideas -- a technique parents, teachers, clergy and other public custodians whose authority we are taught never to question or defy apply with ferocious conviction.

As children we eagerly swallow the “truths” these figureheads concoct to beguile or entrap us, from Santa Claus to the boogey man and the tooth fairy, from the supernatural übermensch who can part oceans, rain fire and spread pestilence and famine, to the “immaculate” birth of a virgin who, visited by “angels” bears a man-God whose recondite pronouncements -- if his biographers are to be trusted -- are conflated into a cult some 300 years after his preordained death, miraculous “resurrection” and subsequent ascension to “heaven.”

Then one day, by word of mouth or the emergence of nascent intelligence, we learn that the pixies and the elves that kindled our imagination and the ogres that populated our nightmares are myth and fraud, as are their principal agents -- our parents. With careful programming, which includes crafty counsel not to wander beyond the limits of time-honored “realities,” we enter adulthood conditioned to accept and encouraged to disseminate other absurdities that owe their being and their irritating persistence to the constant drumbeat of political and religious indoctrination.

No one is “born” a believer or an atheist. No one spurts out of the womb a Jew, Baptist or Muslim, a Liberal or Conservative, a chauvinist or a freethinker. We all come into this world with a blank slate. Parental propaganda, our social climate and assorted constraints mold us into cookie-cutter replicas of our devoted retrofitters. We are all endowed with a brain capable of discerning the truth but we are by now so emotionally mangled by encoding and spellbound by the rote repetition of sanctioned doctrine that we submit to mindless, synchronized rituals alleged to benefit “society.” To survive, the conjurer, the master of doublespeak -- religion -- must cling to fictions that do not exist in the pristine vacuum of an untainted mind but are planted there so they may sprout, tentacle-like, the better to strangle reason.

Held in check, redirected away from prefabricated truths, conflict can bring down the curtains of ignorance and shed light where there is none. It can help change minds, alter perceptions. I think, therefore I doubt, replaces the credo of inflexible dogma. Skepticism in the absence of provable fact has not only propelled science to its phenomenal heights, it has also freed minds trapped in ideological warrens from which knowledge, logic and enlightenment are kept out.

Where does fiction end and fact begin? Do the two ever intersect at a point where reality, improbability and inevitability coexist? Can conflict engender a hyper-reality in which are found the truths that craven men fear to know and cautious men fear to tell? In the perfect geometry of coincidence, will these truths assume an aura of frightening plausibility?