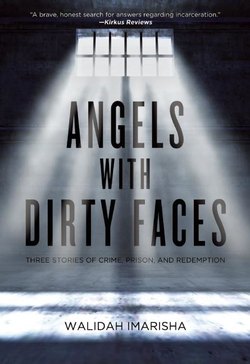

Читать книгу Angels with Dirty Faces - Walidah Imarisha - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

What I Didn’t Know About My Brother

ОглавлениеMy adopted brother Kakamia Jahad Imarisha is charming, charismatic, and complicated—riddled with gaps of darkness and pain that twenty-five years in prison have carved into him. These chasms have been left by being arrested at sixteen and charged as an adult. A sentence of fifteen-to-life hanging like a broken arm. Slowly, these gaps are filled in with fear: the thought of dying in prison floods into the void left as each passing year drains away.

During one visit Kakamia, who never seems to change in my eyes, pointed to his head. “I’m getting old, Wa,” he moaned. For the first time, I saw swathes of gray glistening in the black. It scared me more than it scared him.

Survival in prison is a stroll on a razor blade. Kakamia calls it “a warehouse for people society does not want. Amistad for today,” referencing the famous slave ship where the captured Africans rebelled. You are not meant to survive—not whole, not sane, not with a loving heart. Those who do survive find whatever means they can. To make it, you have to rebuild yourself: rebuild the old you, whatever flaws and weaknesses you brought in, mortar in the gaps of the wall. It’s a never-ending job. Each day new holes are smashed in by the confinement, the inhumanity, the unnaturalness of everything that touches your skin or your tongue, that reaches your eyes or your ears, that lives under your skin and comes out when you’re sleeping late at night, the lights from the tier burning behind your eyelids.

My brother recreated himself so fully, for years I did not know where the renovations took place. In the shadow of prison, I have had to confront my assumptions, my own weaknesses. I have had to force myself to see the person Kakamia was, the person he has become, and explore the fault lines between what is fact and what is true. I’ve had to learn these are not always the same thing.

My brother…even to call him that is a lie that speaks to a deeper truth. Our status as family is not born out of blood or bound by legal documents. Instead, it was a creation we constructed, two lost children in search of a heart that would understand.

Kakamia and I adopted each other as siblings when I was fifteen years old. We’d found each other through a progressive California newspaper I subscribed to. He was advertising his artwork, trying to earn some extra money for the overpriced prison commissary, trying to connect with a world beyond the walls. I was searching for a connection to my Black heritage, living in a small Oregon town, the child of a white mother and an absentee Black father. I thought I was just buying some Afrocentric work to decorate my room. I ended up mail-ordering a brother.

The first art piece he sent me was an African warrior, spear and shield in hand, outlined by the continent of Africa. He called me “my African sista” when he closed the letter. It was one of my first real connections to a Black cultural context. And even our racial identities are complicated. At the time I wondered if I was “really” Black, while his mix of Irish-mutt whiteness and convoluted Puerto Rican Black lineages marked him firmly as “other.”

I have seen pictures of his mother. I saw my own mother staring back, the smiling folds of blonde white womanhood hardened by poverty and decisions made to carry and care for brown children of their making, our color staining and tainting their whiteness.

I have seen a picture of his father. One. Same trim frame, though Kakamia’s has been built up through countless hours of dips and pushups while in solitary, free weights and chest presses when he had access to the yard. They have the same jaunty way of throwing a leg forward and leaning back, as if daring the world to step over the line they’ve drawn.

His father’s skin glows much lighter than Kakamia’s, undarkened by the ever-present California sun. Biology being the convoluted creature it is, I cannot help but wonder at the combinations that produced him.

My own birth was the controlled test group, not the variant. My family is a color test used in elementary school: “Here is what happens when you take white and black: You get brown.” Vanilla/chocolate swirl, no sugar added. That was the sign I stole from a Baskin-Robbins and tacked up under the only picture I have of my mother, my father, and me. No sugar added. Kakamia always teased me, saying I prove girls are made of salt and steel and everything real.

I loved his easy connection with our shared complicated Blackness, and his acerbic humor. We wrote for years, sharing more pieces of ourselves, or whatever pieces we had to offer. He sent me letters in elaborately decorated envelopes. I sent him poems about Black history and alienation. We argued about politics sometimes, but agreed serious change was non-negotiable.

We were young Black mixed-race artists who believed in something larger than ourselves. How could we not end up family?

I feel more strongly connected to Kakamia than many of my actual relatives. When people say to me, “your brother,” I think of Kakamia before I think of my brother born to me of blood. That is the truth. The fact is that our kinship exists only in our minds. We reshaped the world we lived in, re-imagined it to fit our needs. When Kakamia tells stories to people about what I was like as a child, recycling tales I have shared with him and inventing new ones, I do not contradict him. It is true—even when it is not a fact.

Our narrative is something we have constructed together. It is a story we are both writing together, but we can not look at each other’s notes, and are left to guess at what comes next. As the years passed, and I reached out to more people to support Kakamia’s art and poetry, support his appeals for parole, his growing activism, I faced questions that drew blank stares and screeching wheels in my mind. I realized I could not speak of my brother’s story, because I honestly did not know it.

My brother created fictions that were truth—not to steal or to dominate, but to keep pieces of himself alive and whole through the darkest nights. This makes him utterly like every other human on the face of this grasping planet.

Kakamia wrote a poem called “Memories”:

Damn, the memories

No matter how real or made up

They sustain me.

They have become my reality regardless.

The touch, smell, feel, passion, pain

They are now the truth.

My brother has survived so many traumas, most of which began long before he walked through a prison door, or perhaps every door he walked through has been a prison door. Memories can be the bars that cage you in. Like runaway Africans before us, he moved swiftly, under the cover of night, escaping the shackles of memory, following the North Star’s promise of a clean dawn. Its commandment: you must build anew.

When I spoke openly to Kakamia of his puzzle piece past, his response was vitriolic. “You are calling me a liar,” he said. Shocked, I did not understand the erasure of voice by race and poverty welling up in him. The bile of a society that tells him he has no control over his past, and even less over his future, that says he is only what they say and nothing more.

“I thought I was calling you a survivor,” I responded helplessly.

“You’re asking all these questions now, making me pull up things I buried away. Why now? Why after all these years?” he asked.

I told him I had been scared before, that in some ways I still was. I did not explain of what. I didn’t have the words to express the complexities of the creeping fear in my stomach—the fear of hurting him, of offending him, of learning something I couldn’t unlearn. The fear of seeing my chosen family disintegrate like ash under my touch.

“I was scared,” I repeated again, because there was nothing else to say.

Kakamia breathed deep, exhaled forgiveness at my ignorance, my privilege, my judgment. He gave me the gift he has always given me: unconditional support. He told me to go in search of the truth. To ask any questions I wanted. That he would do his best to answer them, as well as he remembered.

“I don’t know what the fuck I remember anymore,” his voice thick on the scratching phone line. “If I had to live with everything that had been done to me, I wouldn’t be here talking to you, Wa. It wasn’t enough to deny it—I had to obliterate it.”

“You made yourself into the man you want to be,” I responded, nodding, though there was no one to see me.

“Is it that simple?” his question full of doubt. “Is it that noble?”

“No,” I said. “But it’s that human.”

“Then ask.”

“You have sixty seconds remaining on this call.”

The recorded message came abruptly, telling us our fifteen minutes had bled away, too quickly as always. We rushed to get in our good-byes and I love yous and we’ll talk soons.

After taking a week or two to reflect and work up my courage, I began simply, in a letter to him, hesitantly. What were you convicted of exactly? When? Where? How old were you?

I felt as if I were interviewing a stranger rather than someone I considered closer than blood.

People who have not done work supporting prisoners, who do not have loved ones behind bars, probably cannot believe that I had called this man my brother for more than fifteen years, but had never asked these questions. But behind the walls, you do not ask what someone has done. If someone volunteers, wants to talk about their case (usually the ones who believe themselves to be innocent), then you listen and provide support. But you do not ask. Because whatever they did to get there, it does not change the conditions they endure. Whatever they did, it does not change the fact that they are human, and that if they actually did harm to another human being, they have no doubt been paid back in full and then some for it. Most of the prisoners I interact with are involved in organizing behind the walls, and are being even more harshly punished for doing so. Like my brother, they have worked to be reborn behind walls, so they might make sense and use of their life.

I can tell Kakamia’s mental state from his handwriting. When you rely so much on letters for communication, you become adept at reading more than just words on a page. Hastily written back, curt but caring, loving wrapped up in irritation and frustration: “Why didn’t you just check the paperwork I sent you years ago? That’s all there.”

I reread the short response. And again.

I did not believe him.

If he had sent me anything, I would have remembered it, I thought incredulously. Why would he tell me something he knows is not true? How could I possibly forget receiving the answers to all these questions?

But before I shot off a reply full of emotion and short on intellect, I cracked open my filing cabinet, crammed to the brim with letters from prisoners, faded articles on new criminal justice legislation, legislation that was now as musty as the paper the article was printed on.

I pulled out the immense manila folder marked “Kakamia,” stuffed to overflowing. I rifled past notes and cards, poems and envelopes decorated in pencil drawn roses.

It was there.

It was all there, just as Kakamia had said. The transcript from his sentencing trial, part of the arrest report, pieces of his crime discussed at a parole hearing. He had worked hard to share the truth with me, and I had worked just as hard to push it away. Pushed it so far I could not even remember the act of erasure.

“Why didn’t you just ask me, Wa? Why do I have to wait until now to find out you have all these questions?”

Why didn’t I ask?

It was not only that as a rule I do not ask people the details of their crimes, or even what they were convicted of. It was not only the fact that even as a journalist, it was still difficult to ask the hard questions, to see fear or pain or anger invade someone’s eyes as I jot down notes.

Honestly, I did not want to know the answers. I did not even want to know the questions. I had done Internet searches on Kakamia Jahad Imarisha (a name I gave to him); his artwork came up, his poetry, the art opening I planned for him, his portrait of us. I had searched for the reborn him. I had never done a search using his birth name. I did not want to see what might have come up: bloody crime scene photos, my brother’s mug shot. Accounts of the destruction he helped create.

“What are you in for?” We do not ask this. But I understand now that for those of us who love people on the inside, not asking those questions protects us as much (or more) than the prisoner. It kept me from seeing my brother through the eyes of his victims. I did not know if I could see him through those eyes, and feel the same way about him. I wanted and desperately needed to see Kakamia as the prisoner who, against all odds, worked to turn his life around, who was committed to changing himself and this world, who used his art as an instrument to implement that change. And he is that.

The truth is always more complicated.