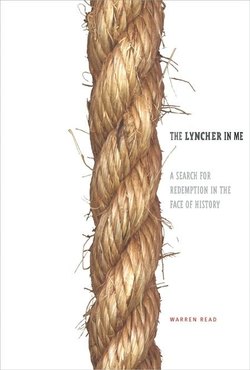

Читать книгу The Lyncher In Me - Warren Read - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Two men are back to back, their bodies slightly touching just at the elbows. A thick wooden pole stands between them, beginning just behind their heels and rising up above their heads, disappearing from the frame of the postcard. Bare skin, arms restrained by their own torn shirts, they are the centerpiece of a gratuitous, macabre portrait.

Lines of white rope encircle their necks; a crescent of even whiter faces surrounds the hanging bodies in a proud display of heroic conquest. They are scarecrows nailed to a tree, hovering just inches above the ground. Of the dozens of bystanders in the scene, only one is smiling unabashedly—a brilliant, ecstatic grin that is all the more incongruous when one notices, nearly touching his right shoe, the head of a third victim, his body lying in a pummeled heap at the man’s feet.

I’ve been among people who I’m sure would sooner see me dead than living with another man and I know that there are times and places that I might be discovered hanging from a hastily fashioned noose or tied to a barbed-wire fence, enveloped by men and women who see me not as a human being but as a category, an aberration, an epithet. I take in the seething hatred in the photo, the objectification of a human being set apart from the masses, and I know that as far-removed as I am from the men beaten and lynched that night long ago, I am not so different.

A shift in my perspective and I’m scanning the figures in the image for something else entirely. The faces surrounding the dead men are stoic, satiated; a few even look uncomfortable. I search apprehensively for the familiar, peering at heads that crane above the crowd, men vying to be captured by the photographer’s lens. There is one whose frown could be my mother’s and my heartbeat falters. Another one has my eyes. A blurred figure just on the edge of the frame has the prominent nose that I’ve come to recognize as my relation, but the jawline isn’t right. This jaw is soft, not squared and chiseled as if from granite and once again I am relieved. It’s not him. I am pulled into the muted imagery of the crowd and before I know it, I become lost trying to force the past into the present. What I am seeking exists somewhere in that photo and I know that as far removed as I am from the men standing in that crowd eight decades ago, I am not so different.

I imagine that I might crawl into the scene, like a photographic version of Alice’s looking glass. And from my vantage point some eighty years later and a thousand miles away, I could actually be in Duluth, on that June night of 1920. I would walk among the mob, passing between them, and perhaps then I would see all sides—the trembling arms, the sweat along the backs of their necks, the deep scratches on the edges of their shiny black boots—and maybe then their evil would become less potent. I would ask them, is this what you really wanted all along? When the morning light shines down on this corner will you return to stand again in smug satisfaction? I would move into the headlights’ beam and stand at the post, reaching out to touch the hands of the murdered, and I would promise them that one day they would be raised again, only this time in admiration and atonement. Then I might turn and go beyond the camera’s eye, back down Second Avenue to the battered jailhouse with its bricks scattered in the street among shards of broken window and maybe there I would find him and I would finally be able to ask, “Pa, do you know what you have done?” And when I take his hands in mine I would show him, make him see the blood, show him that the blood covering his hands has traveled three lifetimes to stain the hands of his descendants. And maybe then he would tell me what I need to hear.