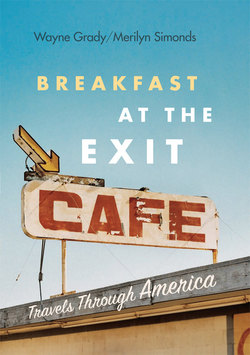

Читать книгу Breakfast at the Exit Cafe - Wayne Grady - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 / ASTORIA

WE continue south the next morning on Interstate 5, a fine drizzle making itself noticeable on the windshield, the wipers giving a cozy kind of syncopated rhythm to the passing parade. Merilyn is in the co-pilot’s seat, navigating with the aid of two maps spread out on her lap, one American Automobile Association map of the entire United States as it appeared fifteen years ago and a smaller, more recent MapArt book open to the state of Washington. Various brochures and booklets are also arranged about her half of the car, but neatly, like the cymbals on a set of drums. She is marking our actual route on the larger map with a yellow highlighter and various alternative routes on the smaller map. Merilyn is both a dedicated planner and a Libran, which means that (a) there must be a plan and (b) every plan must be balanced by an alternative plan. Three alternative plans are better than two, but since that would upset the balance, a fourth plan is required. The small map soon becomes cross-veined with yellow marker lines. In my view, if you aren’t going anywhere in particular, it doesn’t much matter how you get there. To which she replies that if the destination isn’t important, then the route to it must be.

“We could stay on the I-5 to Portland,” she says, “and from there cut over to Highway 101 and go down the coast to San Francisco. I’ve never been to San Francisco.”

“That sounds good,” I say. “In Portland, we could visit Powell’s City of Books. It’s supposed to be the biggest bookstore in the world—a whole city block of books.” I mentally calculate how much room we have in the trunk. Not enough.

“Or we could turn east here and go down the 82 and the 395, which would eventually take us into Yosemite.”

“I’ve never been to Yosemite,” I say. In this state, all the minor route numbers are printed on a portrait of George Washington’s head. The I-5 is lined with the first president’s head on a stick.

“Neither have I,” she says, “but we can also get there from San Francisco. Or we could get off the I-5 and drive over to the coast. Find a romantic little motel somewhere overlooking the Pacific Ocean.”

“Let’s do that.”

As Merilyn returns to her maps, my mind drifts off into something I read in the New Yorker about the differences between what men and women expect when they’re on holiday. According to the article, men want sex, while women want mostly “an interlude of near-monastic solitude.” I’m sure that is a gross oversimplification. Men don’t want just sex. They also want to be left alone. Or maybe they want sex and then to be left alone, whereas women apparently just want to be left alone. But men, I contend, also want other things when travelling: alcohol, a good book, a quiet room, Internet access, great food, courteous and prompt service, other people’s kids kept at a discreet distance, clean water in the pool, the sand raked at night, something interesting to walk to around the point, like a bar. In other words, the same things women want.

“Or we could stay on the I-5 all the way down to San Francisco. That would save us some time. Or we could turn east at Eugene, cross the mountains, and hit the 395 at Burns. What do you think?”

“Fine by me. But wouldn’t that mean missing San Francisco?”

The word on the street used to be that men think about sex every twenty seconds, whereas women think about it once a week or so. This had a scientific ring to it, as though someone had actually timed it. Actually, somebody had: Alfred Kinsey, whose Sexual Behavior in the Human Male made all kinds of claims about what men do and think about based, as far as I can remember, on studies conducted with a group of college students in Florida in the 1950s. What the Kinsey Institute’s report actually stated, however, is that, on average, 54 per cent of men think about sex once or twice a day, 43 per cent think about it once a week to once a month, and 3 per cent think about it less than once a month, if at all. And that women think about sex approximately half as often as men do. The difference doesn’t seem to be enough on which to base an entire philosophy of the fundamental incompatibility of men and women. Besides, the whole Kinsey Report has been debunked. More recent studies show that women think about sex even more often than men do, they just don’t talk about it as much, at least not to men.

“We can see San Francisco anytime,” Merilyn says. “I think I’d rather avoid big cities.”

“Me, too.”

M AYBE we should eat soon,” Wayne says before we’ve driven very far. “I’m so hungry my stomach thinks my throat’s been cut.” It was one of his father’s favourite phrases.

The morning broke with strong winds and rain that seemed pitched in great fistfuls from the hands of the gods. We ignored it, pulling the blankets over our heads. We are habitually early risers, but not this morning. We eased into the day, sitting up in bed with our books and mugs of Starbucks coffee we made ourselves, Wayne spiking his with cream he pilfered from the restaurant the night before. The room was small but cozy, strewn with our things, the air scented with the flowers I lifted from the waste bins behind the Pike Market.

We left with reluctance, pulling out of Seattle close to noon. We weren’t quite in travel mode yet, that frame of mind that makes the car, and the road, the best place in the world to be.

“We’ll eat at one of those great little diners,” I say vaguely.

Breakfast is our favourite meal on the road, the one that proves we’re not home. We often eat lunch at a restaurant, and dinner, too, but the first meal of the day is not normally taken with strangers. At home we cook our porridge with cranberries in the microwave, or grab pieces of fruit and go off to our respective desks. On the road, our appetites become gargantuan and we sit in diners before platters of food heaped with enough calories to last a lumberjack all day. It must be the ancient nomad in us coming out. Stock up while you can, our reptilian brain insists; you never know when you’ll eat again.

We pull off the interstate at an exit to nowhere that we can see, lured by a low wooden building with a huge sign tacked to the roof: All-Day Breakfast. Not a diner, but close enough. Everyone in the place but us seems to be a regular. We stand at the door as the waitress moves among the tables, calling everyone by name.

“Hey there, Bob, how’s it shakin’? Want some more coffee, just a splash? Sure thing, Jake. I’ll be with ya in a minute. And what’s a nice girl like you doing out on a day like this, Sue? Great earrings. It’s set to snow something awful, I hear. Pancakes, the usual? Yeah, I’m here right through Christmas.”

The place is draped with tinsel garlands; Christmasy cut-outs of Santa Claus, Rudolph, and Frosty are stuck to the walls. Elves dangle from the ceiling on red ribbons. A necklace of Christmas lights flashes at our waitress’s throat as she leads us to a table topped with a silver-dusted red plastic poinsettia.

“What can I bring you this morning?”

“I think it’s already afternoon.”

“Honey, here it’s morning all day long. Coffee?”

“Do you have decaf?”

“I’ll have to make some fresh.”

Breakfast is a plate of grease. That’s how the gumshoe would have described it in The Bookman’s Promise, the audiobook we’ve been listening to for the past hour. I order bacon and hash browns with a single poached egg, no toast. Wayne orders eggs and links with biscuits and gravy.

“You ever had biscuits and gravy?” I ask him.

“No.”

“You sure you want that?” I used to work in a short-order kitchen. I know where gravy like that comes from.

“Sure I’m sure,” he says defensively. “Who doesn’t like gravy?”

A few years ago, we took a road trip through Quebec that turned into a search for the perfect confit de canard—duck leg simmered to a tender crisp in its own lard. Before that, a trip to France became a quest for the perfect crème caramel. When my breakfast arrives, I decide that on this drive through America, I’ll be on the lookout for the perfect hash browns. The ones on the plate before me are grated and browned on the grill to the consistency of fibreboard. The yolk of my egg, which should be absorbed by the potato, runs in thin, pale rivulets across the plate. The bacon is deep mahogany and tastes of salt, not pork. Wayne’s biscuits are buried in a grey lava flow.

“How we doin’ so far?” the waitress says brightly, refilling our cups and moving on while we are still deciding whether to be honest or polite. By the time we smile and nod, Wayne’s mouth full of dry biscuit, she is long gone.

But really, I love the place, weak coffee, burnt bacon, greasy potatoes, grey gravy, and all. The morning smell of it. The fuggy warmth. The way everyone calls out, “Bye, Dorothy, Merry Christmas!” as they push through the door into the driving, sleeting rain, saying it the way you’d say, “Bye, Mom.” As if you know you’ll be back soon.

“What’s the best way to get to the Pacific coast?” we ask Dorothy when she brings our bill.

That stops her. She sets her coffee pot down on the table and looks up past the garlands, as if the answer is written on the ceiling tiles. We’ve seen this look before, on the face of a matron on a sidewalk in Pittenweem, Scotland. We’d asked her where to find the Harbour Guest House, the only bayside hotel in a village of not much more than a thousand souls. She’d looked at us blankly. “I don’t know,” she said, “I’ve only lived here these nine years.” Wayne was gobsmacked. “Never ask a local,” I’d said.

“I wouldn’t know,” Dorothy says finally with a laugh. “The Sound is right here, but the coast? I’ve never been.”

WE turn off the I-5 onto Highway 30 just south of Kelso, Washington, and cross the Columbia Gorge. The Columbia River is the dividing line between Washington State and Oregon. Highway 30, as we call it (we still aren’t used to saying “route” instead of “highway”), looks deceptively tame on the map. In reality, it hugs the high land above the Columbia Valley on the Oregon side, twisting and turning like an asphalt snake that is losing its grip on the slippery granite cliffs. The Columbia gleams occasionally far below. There is a logging truck behind us, more impatient to get to the coast than—in its estimation—we are. On the few straight stretches of highway, it comes so close to our tail that the word “Freightliner,” read backwards, fills the rear-view mirror and seems to be snapping at us to get out of its way. On the curves, which arc out over the sheer drop to the river below, it shrinks back as though momentarily looking for a weak spot on our unguarded flank.

“How far to the coast?” I ask Merilyn.

She looks at the map and counts. “About sixty kilometres,” she says.

“Kilometres?” I ask.

“All right, miles,” she says, as though the difference isn’t worth quibbling over.

Finally a road appears on our left, rising away from the river, and I turn abruptly onto it. The truck roars by behind a wall of water, sounding disappointed, like a tomcat whose catnip mouse has fallen down a furnace vent. I turn the car around, and we sit at the intersection for a while looking out across the valley. The rain is still coming down hard and a strong wind is bending some fairly substantial trees above our heads. Before us, far below, we can make out the edge of the river on the Washington side, a fishing village, perhaps, or a farm. Maybe a winery. It looks calm down there.

“There’s a nice-looking hotel in Astoria,” Merilyn says. She spent much of last night surfing the Internet for likely lodgings. “Maybe we should stay there tonight.”

“Sounds good,” I say half-heartedly. We are vagabonds in America, dogged by rain. But Astoria seems too close to Seattle. Shouldn’t we try to make it farther down the coast?

“We have lots of time,” Merilyn says, as if reading my mind. “We’re on holiday.”

PERHAPS IT was our close encounter with the transport truck, or my post-border jitters, but I am still nervous about our trip. I have always had rather ambivalent feelings about America or, at least, America as seen from afar. It speaks a version of our language, but with its own idiosyncratic touches: chinos, sneakers, zee. Maybe that’s why America makes me uneasy: it’s eerily familiar, like a song I don’t remember hearing yet somehow know the words to. Being in America is like walking around in someone else’s dream.

Here is what I have come to believe about America, based, I admit, largely on circumstantial and even hearsay evidence: America is an annoying and dangerous mixture of arrogance and ignorance. Its citizens barge around foreign countries looking for hamburgers and pizza and fried chicken, unaware of, or unconcerned about, or impatient with the possibility that the country they are in might have its own cuisine, customs, economy, political system, and religion with which it is quite happy, thank you very much. It holds that “different” is a synonym for “inferior.” In an Irish pub in Buenos Aires I met an American who told me his hotel was better than mine because his was closer to a Wendy’s.

The dream we’re walking around in is “the American Dream,” which seems to involve having a chicken in every pot, a new Detroit car in every garage, 2.86 television sets in every home, and broadband Internet access on every street. It’s the dream of fame and fortune, of success measured in material wealth. This is a newish version; the original American Dream, as defined in 1931 by James Truslow Adams in The Epic of America, had more substance. It was of “a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity to each according to his ability or achievement.” Nothing would be handed to you on a silver platter: you had to earn it: “It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable.” This is a dream I could live in.

But the dream has changed. In What Is America? Canadian writer Ronald Wright charts how far the American Dream has sunk: “Here are the ingredients of the American Dream: love of the new and dismissal of the old; invaders presented as ‘pilgrims’; hard work both rewarded and required; and selfishness as natural law.”

There is an appalling arrogance and a pitiable naïveté in America, which assumes that the winner of four out of seven baseball games between teams from, let us say, St. Louis and Detroit is by definition the best team in the world. The same attitude caused Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., in 1860, to declare Boston “the thinking center of the continent, and therefore of the planet,” and causes a place like Utah to advertise itself as having “the best snow in the world.”

“America shapes the way non-Americans live and think,” wrote Ian Jack, then editor of Granta, in his introduction to a 2002 issue entitled “What We Think of America.” “What do we think of when we think of America?” Jack asked. “Fear, resentment, envy, anger, wonder, hope?”

All of those things, I would say, and almost in that order. I am in the “fear” stage at the moment, moving into “resentment.” The very thought of Homeland Security rattles me: it’s as if the whole country were a border. It makes the United States a nation of 300 million border guards.

These thoughts are not unique to me: according to recent polls, 37 per cent of Canadians dislike the United States. In fact, it is almost a national pastime, identifying ourselves by what we are not: that is, American.

Nor are the sentiments new. The word “anti-American” appeared in Noah Webster’s first dictionary in 1828 and was defined pretty much as it is today: “Opposed to America, or to the true interests or government of the United States.” It’s hard to imagine being opposed to an entire nation, but consider the remark of an earlier prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, in the House of Commons in 1903: “We are living beside a great neighbour who . . . are very grasping in their national acts, and who are determined upon every occasion to get the best in any agreement which they make.” Pierre Trudeau said something similar when addressing the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in 1969: “Living next to you is in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly or even-tempered the beast . . . one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” People are always saying things like that about Americans, which may be why only 26 per cent of them think they are liked by other countries, and much fewer than that give a damn. But most Canadians agreed with Trudeau when he said, “We are a different people from you and a different people partly because of you.”

When asked to think about America, some Granta contributors thought of things that had arrived in their countries from the United States. The Lebanese writer Hanan al-Shaykh, for example, remembered a gift sent by a cousin who had immigrated to the United States to study aeronautical engineering—a red satin pillow with a picture of the Statue of Liberty, “a good-hearted woman wearing a crown on her head and holding a lamp, a torch.” It is a torch, but I like Franz Kafka’s version better. In his novel Amerika, published in 1927, his hero, Karl Rossmann, looks at the Statue of Liberty as his ship edges into the New York harbour: as Kafka describes it, the woman is “holding aloft a sword,” one of those Freudian slips that no one seems to have caught. But of course it’s a sword—how appropriate! With what else would the United States bring democracy and freedom to, for example, the Middle East? A lamp?

Having grown up sharing a river with America, it is difficult for me to pinpoint any one thing that came to me from across the border. Everything did. In few other places on the continent do Canadian cheeks live in such close proximity to American jowls. Almost everything in the room, including the air, would have been from the States. The dance music my father played, the books my mother read voraciously, all American. The Pablum I ate, although invented in Canada, was produced and marketed in Chicago. During the day, my father worked at Chrysler’s and my mother shopped at Woolworth’s. At school, we played baseball—hardball, not softball, and not hockey. When we got our first television set, I watched Soupy Sales and Bugs Bunny and Popeye, all of whom I thought lived in Detroit. It never occurred to us to be anti-American; it would have been like being against life itself, and not even the good life, just life. Canada was a long way from Windsor; America was just down the street.

That was in the mid-1950s, when the American Dream was already beginning to morph into the American Disturbed Sleep Pattern. I was too young to know about McCarthyism and was blind to racism, but they were as present in our home as Frank Sinatra and Roy Rogers. They “came with,” as the waitresses in Woolworth’s would say to my mother about the Jell-O. My father joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1957, and we left Windsor to live on remote radar bases in the north, DEW Line stations (for Distant Early Warning—distant from whom?) that were built in Canada by Americans during the Cold War so that

Canadians could stand on guard for missiles coming across the Arctic Ocean aimed at Washington, D.C. We imbibed the fear of creeping Communism with our Sergeant Rock comic books, soaked in racism with every episode of Amos ’n’ Andy, and loved every minute of it.

Only later did I resent living the American Dream in Canada. I wonder how I’ll feel about travelling through it in the United States.

“The Cannery Pier Hotel,” Merilyn reads from the brochure, placing special emphasis on its strangely Germanic sprinkling of capital letters, “is a luxury boutique hotel built on the former site of a historic cannery six hundred feet out into the Mighty Columbia River in Astoria, Oregon. The Hotel offers . . .”

“How do we get to it?” I ask. “By boat?”

“ . . . the Hotel offers guests an unparalleled experience in a real working river. Private river-view balconies in all rooms. Fireplace. High-Speed Internet in room. Clawfoot tubs with views. Terry robes.”

I am still feeling anxious.

“Who,” I ask, “is Terry Robes?”

MY estimates are wildly out of whack. Clearly, I have forgotten how long a mile can be. It is late in the afternoon by the time we turn west off the I-5, toward the Pacific. The direction seems all wrong. Aren’t we supposed to be heading home?

US Route 30, the highway we’re on, ends just a few miles down the road, in Astoria. If we turned the other way, we’d be in Atlantic City in just over forty-eight hours. We’d head east through Bliss (Bliss!) and Twin Falls, Idaho, across the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers, skim the southern edge of Chicago, then cut straight through Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, until we hit Virginia Avenue, a few blocks up from the boardwalk in Atlantic City.

Route 30 is the main east-west highway in the United States. It’s not an interstate; it’s a highway. A main cross-country road, like Route 66, except that long stretches of that iconic cross-country road have been replaced by multi-lane throughways that stop for nothing, not a crossroad, not a town, not a megacity. “Life doesn’t happen along the interstates,” William Least Heat-Moon notes laconically in Blue Highways. “It’s against the law.”

This narrow road taking us west to the sea is the only red highway that still runs uninterrupted across the continental United States. Even Route 66 went only to Chicago. Not only is Route 30 the last of its kind, it was the first of its kind in North America. In 1912, Carl Fisher, the man who built the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and turned a Florida swamp into Miami Beach, proposed what he called the Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway. There were already some 2.5 million miles of roads in the United States, but they weren’t connected. Dirt tracks radiated from settlements to farms, logging camps, and mines, petering out at the last signs of human habitation. Fisher’s idea was to connect all those communities with a gravelled road that would run from Times Square in New York City through thirteen states to Lincoln Park in San Francisco, the first transcontinental road built for the automobile instead of oxen, horses, or mules. A Main Street across America—which is how it came to be known.

The road would cost $10 million, with each community along the way pitching in to do the work. To pay the bills, Fisher asked automobile manufacturers and accessory companies to contribute 1 per cent of their revenues to the project. Packard and Goodyear agreed; Ford refused. The public would never learn to pay for their roads if industry built them, Henry said.

Fisher went ahead anyway. To whip up public enthusiasm, he renamed his new road the Lincoln Highway (after the president, not the car, which was later manufactured by Ford). The idea caught on, and so within a few years, highways with names like the Dixie Highway, Jefferson Davis Highway, the Atlantic Highway, and the Old Spanish Trail criss-crossed the country. There was no system of road signs, just painted bands on telephone poles at important intersections, something like the pointing markers on Fremont’s Center-of-the-Universe post.

The Lincoln Highway opened in 1915 in time for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. Most of it was graded and oiled, but parts never evolved beyond muddy tracks; it all depended on the locals in charge.

By the time the idea for Route 30 came along in 1925, government was taking over road building. With bureaucracy came a federal highway system determined to make sense of the myriad quaintly named thoroughfares. To a foreigner like me, the United States National Highway System illustrates the remarkable pragmatism of the American character. Look at a road sign and just by the number, you can pinpoint where in the country you are. Major east-west routes are numbered in multiples of ten, from US 10 across the north to US 90 across the south. Major north-south routes end in 1 or 5, with the numbers starting at 1 in the east and increasing as they move west. The US Route 30 sign we just passed tells me we are in the northern tier of the country, and we’re heading for US Route 101, which runs down the Pacific shore into California.

The Lincoln Highway was severed into several numbered roads, but almost two-thirds of it became US Route 30. The new road was identified, as every road in America is and has been since 1925, with a shield that encloses the number and, at one time, the name of the state. To avoid confusion, all signs showing named highways were taken down.

Where we live in eastern Ontario, planners a few years ago decided to remove apostrophes from road signs. What, the apostrophe takes too much time to print? Too much ink? The curlicue is aesthetically displeasing? Whatever the logic, the result was that Chaffey’s Lock, where Wayne lived for a time, became Chaffeys Lock. The possessive apostrophe, which denoted the name of the person who had founded the town or built the lock, disappeared, though not without considerable outrage from the local citizenry. Likewise, the shift to numbered highways in the United States was not an easy one. As an editorial in the Lexington, Kentucky, Herald noted in 1927, “The traveler may shed tears as he drives down the shady vista of the Lincoln Highway, or dream dreams as he speeds over a sunlit path on the Jefferson Highway, or see noble visions as he speeds across an unfolding ribbon that bears the name of Woodrow Wilson. But how in the world can a man get a kick out of 46 or 55 or 33 or 21?”

The numbers stayed. After all, the original rationale for a federal highway system in the United States was national defence, and soldiers are not sentimental, at least not about other people’s history. But a few Americans refused to see the old highway names disappear. On September 1, 1928, thousands of Boy Scouts fanned out along the Lincoln Highway to install concrete markers, one per mile, with a small bust of Lincoln and the inscription This highway dedicated to Abraham Lincoln.

A rock road from coast to coast; markers every mile to preserve the memory of a revered name: it’s by these grand, sweeping gestures that I know where I am.

Lincoln Highway was decommissioned in 1928. Route 66 went the same way in 1985. The last major route constructed was US 12 on the Idaho side of Lolo Pass, completed in 1962. No new highways have been commissioned since, except the interstates.

In 1962, the year he won the Nobel Prize for Literature, John Steinbeck took a drive on the new interstate. “These great roads are wonderful for moving goods,” he reported, “but not for inspection of a countryside. You are bound to the wheel and your eyes to the car ahead and to the rear-view mirror for the car behind and the side mirror for the car or truck about to pass, and at the same time you must read all the signs for fear you may miss some instructions or orders. No roadside stands selling squash juice, no antique stores, no farm products or factory outlets. When we get these thruways across the whole country, as we will and must, it will be possible to drive from New York to California without seeing a single thing.”

Canada has no interstates. Roads are a provincial concern. It took various levels of government until 1950 to get together to build our one and only cross-country road—the Trans-Canada Highway— which wasn’t finished until 1971. It is our version of Main Street across America: although you can take 1A bypasses around most cities now, Highway 1 itself still barrels through small towns and metropolises alike, stringing them together like beads on a necklace that stretches eight thousand kilometres (five thousand miles) from Atlantic to Pacific.

Route 30 reminds me a bit of the Trans-Canada that brought us west. It feels like a small miracle that this old American road is still here to be travelled, town to town, from one side of the country to the other. Although long stretches of it run parallel to or concurrent with interstates, this historic, eighty-one-year-old route has managed to avoid having its number hung up for good.

“What would you call this road, Wayne, if it didn’t have a number?”

“The Twilight Creek Eagle Highway,” he says.

“Really?” I’d been thinking of something more mundane: the Columbia Road, or Kelso Way. “Why?”

“After the Twilight Creek Eagle Sanctuary,” he says, pointing to the sign near where we’ve pulled off to let a transport truck pass. “Want to go take a look?”

WE’VE pulled off Route 30 onto something called the Burnside Loop, which angles sharply down toward the river. After driving for a mile we come to the sanctuary, where instead of the milling eagles I expect to see, we find two forlorn-looking plaques looking out over a swampy lowland at river level. Here, one of the plaques informs us, is where the thirty-three members of the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery made their camp just over two hundred years ago, on November 26, 1805.

Canadians don’t know much about the Lewis and Clark Expedition. We know Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone because of the television programs their exploits inspired, but Meriwether Lewis and William Clark did far more than those men to open the West to American expansion. In 1804, they were sent by Thomas Jefferson to explore the source of the Missouri River, cross the Rocky Mountains, and find an overland route to the Pacific Ocean. Along the way, they were to make note of anything “worthy of notice.” They found a lot that was noteworthy: Lewis’s journals alone filled a great steamer trunk.

“Great joy in camp,” Lewis wrote on November 7. “We are in View of the Ocian, this great Pacific Ocean which we been So long anxious to See.” To mark the occasion, Clark carved his initials and the date on a handy pine tree. Now they were moving back and forth across the river mouth, looking for a place high enough above the tideline to spend the winter. Like us, they hadn’t booked ahead.

Out here in the wilderness, almost a year’s travel from the Thirteen Colonies, the democratic principles of the freshly fledged nation prevailed. By a vote of the entire expedition—including York, Clark’s black “manservant,” and Sacajawea, the young Shoshone wife of one of the French-Canadian guides—the corps decided to make its winter camp on the south side of the Columbia, where elk were more plentiful, near what is now Astoria, at a place they named Fort Clatsop.

The Corps of Discovery scheme was inspired by Alexander Mackenzie, who trekked across Canada and reached the Pacific Ocean near Bella Coola, in what is now British Columbia, in 1793. Jefferson read Mackenzie’s account of his trip avidly, passed the book on to Meriwether Lewis, who at the time was his personal secretary, and began planning an American version of it, with Lewis in charge. Mackenzie even carved his name and the date of his arrival—not in a tree, but on a rock. I like the idea that the Lewis and Clark journey, one of the defining myths of American history, had its origins in a Canadian expedition that few in Canada today remember.

Standing on the slippery platform of the Twilight Creek Eagle Sanctuary, at twilight, looking down at the great river where the expedition camped, I understand what it is that has fixed this journey so securely in the American imagination. We have a river, we have a small band of purposeful men floating down it, and we have an ocean. What could be more American than that? It is Apocalypse Now. It is Huckleberry Finn. Clark even had his single-named slave, York, with him. But unlike Huck’s companion Jim, York isn’t a runaway. In Huckleberry Finn, Jim is the one character for whom freedom meant something tangible; his eventual emancipation elevates the novel to the status of myth.

In the Lewis and Clark story, the loyal and obedient York is not escaping from anything. In fact, he is scarcely visible. He is given no voice other than that of an animal when he is amusing some Indian children and is mentioned barely a dozen times in the three years covered by the narrative, and then only matter-of-factly, as in “set out at 7 o’clock in a Canoo with Cap Lewis my servant and one man . . .”

Because York is denied any role other than that of a slave, the Lewis and Clark expedition, which was essentially a scientific and commercial enterprise, becomes a different kind of epic journey, one that also delineates and defines the American spirit. If Huck and Jim represent the fictional way Americans would like to see themselves—as simple, honest, and freedom-loving adventurers—then Lewis and Clark reveal the true nonfictional nature of their national consciousness: entrepreneurial and freedom-loving, except when it came to Manifest Destiny and slavery—in other words, the rights of others. When the expedition was over, York asked Clark for his freedom. Clark refused.

The setting sun is coming from the west, casting long shadows over the Seal Islands. I realize that this is my first real view of the Columbia River. And that we have come here by land from Canada, after crossing the continent; in a sense, we have combined the journeys of Mackenzie and Lewis and Clark. I look around; there are several sizable trees, dripping with rain but suitable for carving. Unfortunately, I have left my Swiss Army knife at home; I didn’t want to worry about it as I crossed the border.

MUTELY we drive through the gathering night toward the end of our second day on the road. The radio is off and Wayne is somewhere in his Lewis and Clark reverie, but even so, the air is filled with sound: tires on asphalt, wipers on glass, the bellow of a ship’s horn on the river below, the wigwag of the railway track we just crossed.

True silence—natural quiet—is a rare thing. Gordon Hempton, an acoustic ecologist across the river in Washington State, has spent most of a lifetime searching for places where the sounds of nature might be recorded without man-made interruption. There aren’t many left. He’s made a few MP3 albums of the sounds of silence: “Forest Rain,” “Spring Leaves,” “Old Growth.” I like the idea of listening to a forest growing.

On Earth Day 2005, Hempton decided to defend a bit of wilderness from all human-caused noise intrusion. His “one square inch of silence” is in the Hoh Rain Forest of Olympic National Park, 678 feet above sea level and a two-hour hike in from the nearest trail, the exact location marked by a small red stone placed on top of a moss-covered log at 47° 51.959’ N, 123° 52.221’ W. He even convinced airlines to reroute their flight paths around the park.

Hempton defines silence as “the total absence of all sound. But because the whole universe is vibrating, there is no true silence— though silence does exist in the mind as a psychological state, as a concept.”

Wayne and I are silent, but it isn’t the silence of solitude. Even without speaking, he is part of my mental space. I wonder what he’s thinking, if maybe I should say something funny or smart. What kind of mood is he in? Should I bring up Christmas, how much I miss the kids? Or the novel that I so much want him to read. Maybe I should find something in the brochures to talk about, try to connect us with the river that is slipping by outside.

And what is Wayne thinking? Is he sitting in his silence the same way I sit in mine?

Probably not. Researchers at the University of California recently found that the amygdala, that almond-shaped structure nestled on either side of the brain, behaves differently in men and women at rest. When men are relaxed and quiet, the right amygdala is the more active one, while in women, it’s the left. What’s really interesting is the region of brain that the amygdala is talking to. In men, it’s communicating with the visual cortex and the striatum, which controls vision and motor actions. In women, it’s connecting to the insular cortex and the hypothalamus—the interior landscape. I’m thinking about our relationship; Wayne’s wondering where he can pull over to pee.

“In human intercourse the tragedy begins not when there is misunderstanding about words, but when silence is not understood,” Thoreau wrote. It’s hard to believe he was never married.

After three months working alone on my book, I don’t find it easy being trapped in this little Toyota with another person, even one I love more than I ever thought possible. How can I think in this Echo? Wayne won’t be quiet for long. He has a penchant for golden oldies: he worked as a DJ in high school and knows all the words to all the songs up to about 1968. He has quite a good tenor, of the Gerry and the Pacemakers variety, so I don’t mind sitting through endless verses of “The Sound of Silence,” “Twenty-Four Hours from Tulsa,” and “When I’m Sixty-Four.” But driving through this blackness, I long for the Blues. Maybe a little Dr. John crooning “Such a Night,” or Sippie Wallace doing “Suitcase Blues,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe belting out “Didn’t It Rain,” or B.B. King. I can almost hear him . . . Gonna roam this mean ol’ highway until the break of day.

It’s not really a mean ol’ highway. In fact, there’s something about driving through the gathering nightfall in the rain that feels almost cozy. Not fearsome or alien, though I can see how some might see it that way. The damp darkness outside our windows is impenetrable; the headlights obliterate the landscape, force our eyes down wavering tunnels spiked with glinting needles of rain. There’s a rhythm to the slap of the wipers that lets me sink into myself, just as Wayne has sunk into some contemplative place of his own. We are making this journey together, but separately, too.

WE’VE been vagabonding in America, meandering the day away, eating in the car, drinking water from our metal bottles. We’re more than ready for dinner. We arrive in Astoria just as the street lights are making pale, yellow smudges in the misty rain, but even so the streets look dark and deserted. Few of the storefronts are lit up, and our hopes of finding a quiet, excellent restaurant fade.

The main thoroughfare, Commercial Street, which we’re on, is a miracle of Victorian bakeshops, olde innes, souvenir and gifte shoppes, and the like. The Liberty Theater, built in 1925 and recently featured on HGTV’s Restore America television series as one of its twelve American Treasures, appears to be dark tonight, and is likely to stay dark until spring. Ah, well. According to the Visitors Guide, the town fairly hums with life in the summer: visitors flock to the Fort Clatsop National Memorial, and on the waterfront, a “beautifully refurbished” 1913 trolley car runs between the port and the East Mooring Basin. But it’s winter, and the town seems moribund. We drive through the business section without stopping and soon come to a huge, steel-girdered bridge that soars upward and off over the Columbia River, somewhere to our right. Almost directly under it, jutting out into the river, is the Cannery Pier Hotel.

The building was built as a fish cannery back when salmon runs in the Columbia River were the biggest on the coast and Astoria was the second-largest city in Oregon, after Portland. Most of the fish plants shut down in the 1940s. Although this building has been fully restored and turned into a boutique hotel, the area around it still looks fairly desolate in the dark. To get to the parking lot, we have to ease the Echo over a dilapidated dock that must still be on the town’s to-be-improved list.

The hotel looks like a Mississippi riverboat moored to the dock, flags flying, lights ablaze, ready to cast off and float off down the Columbia. Merilyn goes in to negotiate a room while I sit in the car, twirling the radio dial to find a baseball game. Instead I get Miles Davis, so I turn off the wipers and let his smooth, muted trumpet ease the rivulets of rainwater down the windshield. When he was on the road, Davis used to send his wife, who was white, into hotels to secure them a room, figuring she wouldn’t be turned away and might even get them a deal. I’m doing the same thing. The Cannery Pier looks expensive, and after our small flurry of spending in Seattle, Merilyn and I have decided on a limit of $100 a night for accommodation and another $100 a day for meals, gas, and various other necessities, such as books and wine. It’s an arbitrary figure, but this is our first night and we think we should be setting ourselves a good example.

Merilyn comes back to the car smiling. “The woman at the desk was reading a book,” she says.

I take that as a good sign. “What was the book?” I ask.

“I couldn’t see the cover,” she says. “She told me the rooms were $160. I told her we didn’t want to pay more than $120, and she said, ‘I can do that.’”

A hundred and twenty is more than a hundred, but maybe we can skip a meal tomorrow, or a quarter of a meal over the next four days. Instead of steak, fries, salad, and a glass of wine, I’ll just have the steak, fries, and wine. A budget is a budget.

The foyer is a marvel of modern architecture, all plate glass and weirdly angled Douglas-fir beams bolted to gleaming hardwood floors.

I admire the view over the river, with the bridge sweeping overhead like an inspired brush stroke. Classical music plays softly from speakers hidden behind fabric wall hangings. The night clerk has gone back to reading in a soft leather chair by the window. A thick paperback with a glossy cover, but at least it’s a book. She gets up and pours us each a glass of wine, “complimentary to our guests,” she says. Merilyn doesn’t drink, so I take hers, too, as we climb the carpeted stairs to our room.

It is spacious, with, as advertised, a fireplace, a narrow balcony overlooking the river, a claw-footed tub with a view, and, yes, Terry Robes hanging in the closet.

“It’s gorgeous,” Merilyn says, running the bath. I find a corkscrew on the side table and agree.

In the morning, we go downstairs for our free continental breakfast and carry it up on a tray to our room. We’re not being anti-social; there are no other guests in the hotel. From our balcony, we watch a huge grey freighter slip upriver past the hotel, inches, it seems, from our wrought-iron railing, so close we can see sailors through the portholes having their bacon and eggs and hash browns. American coots and western grebes paddle about in the ship’s wake. On an adjacent, equally dilapidated pier, a lone fir grows improbably from a pile of rotting boards. It looks like a Christmas tree. We note with approval that no one has crawled out onto the pier to festoon the tree with coloured lights and tinsel or heap fake Christmas presents around its base. Maybe I could like it here, after all.