Читать книгу Green Mangoes and Lemon Grass - Wendy Hutton - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

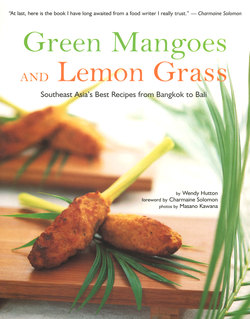

Оглавлениеfabulous flavors from bangkok to bali

Southeast Asia is my adopted home. I came intending to stay two or three years. Thirty-five years later, I'm still here. Ho w could I possibly tear myself away from such a fascinating region which also — or could this be the main reason? — offers some of the world's most sublime food.

When I think of the countries I have explored throughout Southeast Asia, I find it difficult to separate the people and places from the food. Cambodia is the slap-in-the-face odor of a jar of fermented fish on a houseboat on Tonle Sap lake. Thailand brings back my amazement at learning just how many wild plants are edible while helping forage for our evening meal with a hill tribe. Laos reminds me of facing skewers of tiny whole frogs in a morning market when I really wanted something less challenging for breakfast.

Burma sparks memories of a version (pretty dreadful too, to be honest) of British Christmas fare in a colonial-era guest house in the misty hills, with local kids singing carols outside. Bali is recollections of helping prepare endless intricate food offerings for a temple festival, while the sophisticated side of Singapore takes a back seat to memories of countless great meals whipped up in a wok at the local food stalls.

You might wonder how could there be any common thread running through the cuisines of places as far apart as Burma and Bali, a region with literally hundreds of different ethnic groups. And it's not just the people that are different. Southeast Asia is not all lush green paddy fields and waving coconut palms. Central Burma, for example, is downright arid, a dramatic contrast to the fertile corridor of the Mekong river, threading through Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia before sprawling in a maze of waterways in the Mekong delta of Vietnam. But despite variations caused by quirks of geography, most of Southeast Asia is hot and humid, so the basic foods are similar everywhere from Burma to Bali.

The way people put these ingredients together in the kitchen is partly the result of history. The region has seen the rise and fall of mighty Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms, leaving awe-inspiring remains such as stone stupas studding the plain of Pagan in Burma; astonishing temples, gateways and moats in Angkor, Cambodia; and exquisite Hindu remains in Java, Indonesia.

But history is about people as well as kingdoms and monuments, and it is the people who produce the cuisine. The mosaic of ethnic groups in some parts of Southeast Asia today is the result of different tribes from southern China moving gradually into Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand. More recent waves of immigration brought hundreds of thousands of Chinese to what was then Malaya, to Singapore, Indonesia, and Thailand. Indians spread across the border into Burma, while thousands of southern Indians were brought as laborers to Malaya and Singapore. These immigrants — and also the period of colonialism, which only Thailand escaped — introduced new ingredients and cooking styles, helping shape the food of Southeast Asia to varying degrees.

If you were to use just one phrase to sum up Southeast Asian cuisine, it would be "hot, sour, sweet, and salty," a concept is surprisingly similar to the Chinese principle of "balancing the five flavors" (adding bitter to the four flavors of Southeast Asia). Sometimes this blending of hot, sour, sweet, and salty comes altogether in just one dish, or it is spread over a series of dishes sen/ed with rice. For example, order a simple bowl of noodle soup in Thailand, and you'll find everything you need to balance the flavors set out on the table before you: hot chilies, sour lime wedges or rice vinegar, sweet cane sugar, and salty fish sauce (and, for a textural contrast, coarsely crushed toasted peanuts).

There's no denying the Chinese influence, especially in the towns and cities. You'll see the conical Chinese wok in countless local kitchens, and find cooks following the Chinese technique of stir-frying. And just about everywhere, you'll find bean sprouts, bean curd, salted soybeans, noodles and — where fish sauce does not reign supreme — soy sauce, all introduced by the Chinese.

But despite these influences, Southeast Asian cuisine is unique. For me, the secret lies not just in the blending of hot, sour, sweet, and salty seasonings but in the incredibly fresh flavor and herbal aroma. Fresh seasonings, which are often crushed to a paste, include juicy purple shallots, garlic, ginger, chilies of different colors and intensities, blindingly yellow turmeric, and blush-pink galangal.

Herbs are used with almost wild abandon. The tang of citrus is personified in the intense flavors of lemon grass and kaffir lime leaf. Wild jungly odors come through in polygonum or Vietnamese mint, in saw-tooth coriander and rice paddy herb. Several varieties of basil hint of aniseed or other spicy savors, while the mint seems more pungent than any Western variety. There's also the distinctive fragrance of fresh coriander leaf, spring onions, and dill — and these are just the most commonly used herbs.

Although some dishes (especially in Thailand) are uncompromisingly hot, chilies are generally used sparingly in main dishes, appearing in a side-dish such as a sambal, as dried chili flakes or pickled, so you can adjust the heat to suit your taste.

Unlike Indian cuisine, Southeast Asian food doesn't normally contain large quantities of spices, with the exception of parts of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Burma. Elsewhere, cooks usually restrict themselves to a little freshly ground coriander, a pinch of turmeric, a stick of cinnamon and a whole star anise, or black pepper crushed with garlic and coriander root.

The appetite-sharpening sourness of many dishes has a wonderful fruitiness and fragrance so much richer than any vinegar; this comes from limes, tamarind juice, or wild acidic fruits, as well as tomatoes, star fruit, and pineapple. A perfect balance is often struck with palm sugar, fragrant as well as sweet, although regular cane sugar is also widely used.

There's no denying there's something fishy going on in Southeast Asian kitchens. Various forms of fermented fish are used throughout the region, yet amazingly, their alchemy is such that the resulting dishes don't actually taste offish. Rather, they have a saltiness, an aroma, and a complex note that is difficult to isolate. First and foremost is fish sauce, an amber, fragrant, and salty liquid made from fermented fish, while in Cambodia, Laos, and southern Thailand, the pungency of fermented fish paste is particularly appreciated. Another fishy essential used virtually all the way from Burma to Bali is dried shrimp paste, added sparingly but with great effect. Dried prawns also add a wonderful depth and texture to many dishes.

So what do cooks combine with all these herbs and seasonings? The staple food throughout most of the region is rice, eaten with cooked and raw vegetables, as well as unripe fruits which are eaten in salads or cooked. There's fish from the rivers, lakes, and sea, and to a lesser extent, poultry and meat. This is generally pork (in non-Muslim countries), water buffalo, or beef, although in isolated rural districts, wild game and all kinds of less conventional creatures are tossed into the cooking pot or onto the grill.

Fresh and dried noodles are popular. These are mostly made from rice flour, although wheat noodles and transparent jelly-like noodles made from mung beans are also found. Rice flour is also used to make both fresh and dried wrappers for food, particularly in Vietnam.

Along the coasts and in the more fertile regions, coconuts provide creamy rich milk for many soups, stews, curries, and desserts. If we leave aside coconut milk (which, sadly, is fat-saturated), most Southeast Asian food is healthy. Lots of vegetables are eaten, many of them raw. Grilling, steaming, and simmering are the most commonly used cooking methods, and although some food is deep-fried, it is much more common to find ingredients stir-fried in just a trace of oil.

Despite so many shared elements, every country in Southeast Asia has its own special ingredients and dishes. The food of Burma has been influenced by its powerful neighbors, India and China, as well by geography. The coastal people prefer fish in all its forms, while the Burmese living in the dry central plains around Mandalay and on the Shan plateau replace fermented fish and prawn pastes with distinctive fermented bean wafers or fermented lentil sauces.

The cuisine of Thailand is probably the most varied in Southeast Asia, ranging from the generally hot, sour food of the north, through the simple yet striking dishes of the poorer northeast, down to rich coconut-milk dishes in the south, with sophisticated royal cuisine found in the capital. Thai food is the most emphatically flavored of all Southeast Asian cuisines, almost always a little hotter, sourer, sweeter, and saltier, yet always perfectly balanced.

Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were all part of what the French colonials referred to as Indochina, yet they are quite different. This is cleverly summed up by the local saying: "the Vietnamese plant rice, the Lao watch it grow and the Cambodians listen to it growing." One thing they share in common is excellent French bread, a most welcome colonial legacy

Vietnamese food is scintillating, sophisticated, and often deceptively simple, with a subtle balance of flavors. The Vietnamese have a passion for wrap and roll, using wafer-thin dried rice papers, freshly steamed rice pancakes or lettuce leaves to enclose an amazing range of food. Rolls and barbecued meat are eaten with a platter of fresh herbs bean sprouts, and salad leaves that accompanies just about every meal, even a simple bowl of noodle soup.

Most Laotians prefer glutinous or sticky rice to normal rice as their staple (as do the Thais living on the Lao border). Water buffalo is the most popular meat, but there is still a remarkable array of anything that slithers, jumps, and flies — frogs, eels, tiny birds, grasshoppers — in local markets. A large percentage of Lao plants are still gathered in the wild, including bamboo shoots, young leaves, rhizomes, flowers, and even a type of river algae.

Cambodia food is perhaps the most "pure" in the region, using fewer introduced ingredients than its neighbors. It is also the only country in the Southeast Asia where black pepper (the original source of heat before chilies were introduced) is still largely preferred. Fresh lemon grass, galangal, kaffir lime leaf are the most popular herbs, and freshwater fish (especially from the huge Tonle Sap lake) is much more common than meat.

Malaysia and Singapore share many culinary similarities, largely the result of waves of Chinese and Indian immigrants. The original inhabitants, the Malays, form around 50 percent of the population of Malaysia, while Singapore is predominantly Chinese. Like most Indonesians, the Muslim Malays do not eat pork; their food is often rich in coconut milk, generously spiced and frequently chili-hot.

The earliest Chinese immigrants to Singapore, and to Penang and Malacca (both now part of Malaysia) gave birth to an exciting cross-cultural cuisine blending Chinese and Malay ingredients and cooking styles. Known as Nonya cuisine (after the term for the women who created it), this sometimes contains Burmese, Thai, and Indonesian influences as well — a true Southeast Asian synthesis.

Indonesian cuisine differs considerably from one region to another. Best known, perhaps, are the mild, often sweet flavors of Java and the richly spiced, chili-hot and fragrant food of West Sumatra. Hindu Bali — the only area in the world's largest Muslim nation to enjoy pork — offers some of Indonesia's most exciting dishes.

Over the years, I have been amazed by the generosity of cooks throughout Southeast Asia. I don't think anyone has ever refused to let me peer over their shoulder, or been reluctant to explain an ingredient or a technique. I have been able to pass on some of this in books I've written about almost every individual Southeast Asian cuisine, but I feel it's now time to put some of my favorite recipes together in just one book.

This highly personal selection includes only a fraction of my favorites (my publisher refused to let me include them all). I've resisted the temptation to include purely Chinese or Indian food found in places like Singapore and Malaysia, concentrating on the indigenous dishes, or those which show a fusion of foreign and local cuisines. And I've avoided the most esoteric recipes as I know it's not always easy to find such things as fresh palm heart, turmeric flowers and fermented sticky rice in your local Asian store.

I've had a fabulous time "living the food," gathering, cooking, and enjoying these recipes over the years. I just hope you have half as much fun trying them out in your own kitchen.

You may find that the grouping of recipes within this book somewhat different from the conventional approach. It is worth remembering that in Southeast Asia, unless a one-dish meal such as noodles is being served, all dishes served with rice are generally placed on the table at the same time, for everyone to share.

This means that the grouping of dishes is not a hard and fast rule.Thus, within this book, snacks, starters, and soups are grouped into one chapter, as are salads, rice, and noodles. Because some recipes take much longer than others to prepare — and because time is often an important factor in busy modern lives — I've grouped various poultry, seafood, and meat dishes into two categories. A Flash in the Pan includes dishes that can be whipped up in under 30 minutes, while Time to Impress includes those recipes which take a lot longer, either in preparation time or actual cooking. Side dishes, which include various dips, relishes, pickles and cooked vegetable dishes, are grouped in the chapter A Little Something on the Side. The last category, Sweet Endings, says it all: delicious sweets that can either bring a meal to a close or be served, Southeast Asian-style, as a between-meal snack.

So free up your approach to food. Everything is flexible. Enjoyment is paramount. Welcome to the feast!