Читать книгу Malaysia: Portrait of a Nation - Wendy Khadijah Moore - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe Land Where the Winds Meet

“Of course she had read novels about the Malay Archipelago and she had formed an impression of a sombre land with great ominous rivers and a silent, impenetrable jungle. When a little coasting steamer set them down at the mouth of the river, where a large boat, manned by a dozen Dyaks, was waiting to take them to the station, her breath was taken away by the beauty, friendly rather than awe-inspiring, of the scene. The gracious land seemed to offer her a smiling welcome.”

– W. Somerset Maugham, ‘The Force of Circumstance’ (1953)

Measuring up to a metre in width, the world’s largest flower the parasitic, leafless rafflesia, is found only in the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra at altitudes of 500 to 700 metres.

Kuala Lumpur’s skyline is dominated by the 451.9-metre-high Petronas Twin Towers, among the world’s tallest buildings, designed by Cesar Pelli and built between 1993 and 1996.

Some places are not what they seem. Like people, some are easy to get to know, their personalities on show for all to see, and once known they remain constant, caught in a kind of timelessness. Others are more difficult to penetrate, not only in their geography but also in their psyche. At first you think you know them, but then they change again, chameleon-like, and by degrees they become stranger. For me, Malaysia is this kind of place. It has been like this ever since my first visit over three decades ago. It is a country that offers almost unparalleled diversity, from it geographical contrasts to its kaleidoscopic population. Here is travel in variety and depth of feeling.

Immersed in Kuala Lumpur’s Blade Runner-like cityscape, I can marvel at the world’s tallest buildings, but also spy the world’s oldest rainforests in the hills beyond. I can cruise the superhighways and be numbed by the banality of concrete suburbia, then take an exit and emerge in an idyllic Gauguinesque village. I can spend the morning mall-crawling through designer boutiques and the afternoon exploring the crowded lanes of ancient port cities, or I can even escape to a tropical island and play “Survivor” or join the lotus eaters at some of this planet’s most exclusive resorts.

At Penang’s tourist mecca of Batu Ferringhi, beachgoers don’t have to walk far to buy a locally made batik sarong.

Malaysia is an old land, but an imagined nation, inheriting its political borders from the imperialist powers that carved up the great Malay World into Dutch and English spheres. The Malay Peninsula, formerly Malaya, dangles like an appendage from Asia’s southeastern extremity, while across the South China Sea are the states of Sabah and Sarawak on the great jungled island of Borneo. Combined, the nation they create is home to a diverse population of almost 24 million, with a geography that is equally varied. It offers a journey through both space and time. It is a nation that exists in the past and present in a kind of duality - a balancing act that is at the heart of understanding the paradox that is Malaysia. Let me explain.

There are two windows in my hotel room in Kota Bharu, the far-flung capital of the Malay heartland, Kelantan. One overlooks the roofs of wooden houses, just discernible through the verdant overhang of mango trees and coconut palms. From here come the sounds of cockerels’ cries and the “tock-tock” of stone pestles against mortars, grinding spices. Reassured by the past, I open the other window, where instantly I am confronted with the face of the future. The drone of air-conditioners floats across a tarred parking lot where Mercedes Benzes and locally made Protons stand in gleaming ranks where not so long ago a village stood. Malaysia is like the hotel room, a limbo land, albeit a comfortable one, where you exist somewhere between the past and the present - the divide between traditional and contemporary.

At Kuala Muda, in the south of the rice-bowl state of Kedah, kampong houses are set high on posts amidst tall coconut palms.

At Bachok, in Kelantan, fishermen still put to sea in wooden praus that are launched from the beach.

It is not a new concept though. Malaysia has always been adept at re-creation, and its undeniable success has been to constantly absorb change while somehow staying the same. Geography has played a major role. At the heart of Southeast Asia, straddling the ancient trade routes where the monsoon winds meet, this land has attracted visitors for thousands of years, bringing with them their cultures, languages and religions. This is the changing face of Malaysia. At the same time, there is the constant of that which has always been.

Kite makers still practice their craft in Kelantan, where tradition, pastimes such as kite flying continue to be popular

This dualism has long been known, beautifully expressed by the ancient Malay saying, “adat (tradition) comes from the mountains and religion from the sea”. The mountains, home to the world’s oldest rainforests, are a wonderful metaphor for the past. Here live the remnant tribes of Orang Asli, “the original people”. Here shamans still go to acquire their knowledge from fairy princesses. Despite the shrinking of the vast forests, they harbour an astonishing menagerie and a bewildering flora that is still being discovered even as it is being lost. The dense green heart is the source of the mystery that has long fascinated travellers, and it continues to exert a powerful effect on the national psyche.

Six-lane highways cleave mountain ranges shrouded in forests, but few people venture into the rainforest - they drive through it, cocooned in air-conditioned comfort. Yet folk memories remain. They search for the wayside stall that sells jungle durians, renowned for that subtle, mysterious taste that the orchards can never duplicate. Traditionalists who go in search of herbal remedies, or woods for crafts, still chant special mantras to the guardian spirits before entering that other, older world.

Change always came from the sea. The Malays came in their praus, and the rise and fall of their great kingdoms, from Kedah to Melaka, waxed and waned with the seaborne trade. The Indian, Chinese and Arab traders brought their religions and their traditions, although these were never a threat to Islam. The seas brought the colonial powers — the Portuguese, Dutch and English - whose surviving cultural fragments added to the exotic mosaic that is Malaysian culture and history.

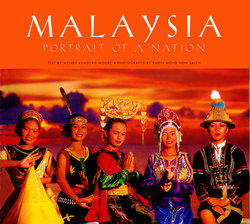

With tradition: fast disappearing on the west coast, stage-managed events such as the “Colours of Malaysia” festival, held at Kuala Lumpur’s Merdeka Square, is a highlight of the tourism calendar

Climbers approach the top of Mount Kinabalu, Malaysia’s highest peak at 4, 101 metres, that dominates the landscape of Sabah.

Golfers enjoy a game at Tanjung Aru in Sabah.

Dualism is often present in everyday life. Malaysians have a knack of incorporating both old and new into their lifestyles. Along the Kelantan coast, motors have replaced sails in wooden fishing boats., the old carved spar holders are now kept merely for show, and the symbolism behind the carvings and colours has been forgotten. A world away, in the luxury homes of the capital, conversation can easily swing from the fluctuations of the stock exchange and the horsepower of the latest BMW, to talk of an amorous politician who wooed his new wife with a love potion of jungle herbs, or how the fortunes of a well-known company have soared since a pair of guardian lions were installed in its high-rise office in line with feng shui precepts.

Back at the Kota Bharu hotel, as I watch from the hotel window, a dozen families walk to their vehicles, all emblazoned with stickers saying “Mystery Drive”, and take off. It seemed almost uncanny that I, too, was there in search of mystery. Only our methods were different - they were on an organized, motorized treasure hunt, while I was on a personal journey - but we were all in our own way looking for clues.

Kelantan’s estuaries are home to Malaysia’s most colourful fishing fleet, known as bangau boats after their unique carved and painted “stork”-shaped spar holders of the same name.

clockwise from top left: Indian garlands for sale in Johor Bahru; a woman puts out salted squid to dry in the sun at Marang in Terengganu; ritual prayers are performed in a Penang temple; an elderly Chinese attendant sells joss sticks at Penang’s Snake Temple; women harvest rice by hand in a Melakan rice field; an Indian fortune teller operates from a Penang pavement; women traders dominate at Kota Bharu’s colourful Central Market; and a Bajau horseman participates in an annual parade in Kota Belud, Sabah.