Читать книгу UPSTAGED BY PEACOCKS - Wendy Macfee - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

“WHEN BIRDS DO SING…”

BIRDS

On a balmy summer’s evening in the gardens of the Cornish mansion, Trevarno, while an entranced audience watched the performance of a Shakespearean play beneath a magnificent tree, a peacock firmly took up his position between the play and the audience. Spreading his magnificent feathers to their utmost height and width he posed triumphantly,

“Don’t look at them, look at me,” his posture proclaimed, “I am really worth looking at!”

Of course he won and the audience ignored the actors who were trying to continue with the play. It was the culmination of a long-held contest between actors and peacocks for possession of the site. In fact the tree held the roosts of the peacocks who wished to go there to sleep long before the plays presented each year there had come to the end of their fifth acts. Loud peacock shrieks of protest throughout the performances had always accompanied the well-resonated voices of certain actors, destroying the hauteur of their stage presence. Anne, who ran the company, played its music and performed small roles in it, was secretly pleased at the ability of the peacocks to put down these actors whose conceit she found irritating. She herself was fairly soft voiced and when she played the musical instruments which accompanied the play, the peacocks seemed to be soothed, so she considered them to be on her side.

Much to Anne’s secret pleasure, in 1980 peacocks objected strongly to other arrogant male actors’ voices in a performance of As You Like It in the theatre in Holland Park, London, screeching their protests in competition with the dialogue. However one of these same peacocks became enamoured of the blue-coloured car of one of the loud-voiced actors, continuously circling it in a loving rotation. It was assumed that the colour blue was the source of this misplaced adoration and that the peacock hoped that the car would ultimately transform itself and reveal its true identity as a female of the species.

Peacocks continued to upstage Theatre Set-Up performances in the grounds of Kirby Hall, Nottinghamshire. In response to Anne’s surprise at the intelligent interest that one of the peacocks there was showing in the company’s setting up of the play, the custodian instructed her that all creatures have different personalities and levels of intelligence and that this particular peacock was very sociable, greeting most visitors to the sight and showing an alert interest in everything that was going on. This interest continued throughout the performance, the peacock taking up a stance at the side of the stage area and providing a continuous shrill commentary on the stage action. Another peacock hen supplied a rival diversion by encouraging her chicks to climb up a small mound to the side of the stage area. They had little success in doing this and their falls back down the slope caused considerable anxiety to the watching members of the audience.

In 1983 a beautiful white peacock at Sudeley Castle, near Cheltenham was very surprised to see a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream being performed by the carp pond in the castle gardens. In order to satisfy its curiosity it stepped confidently through the audience to the edge of the pond, watched the play for a while and then strode contemptuously off.

However the loudest bird commentaries on the action of Theatre Set-Up’s performances were made by the seagulls perched on the ruined walls of the Peel Castle and Cathedral where the company played on the Isle of Man. Fortified by fish from the adjacent sea and its fishing fleet, these birds screeched resonant disapproval of the unusual evening presence of people near their nesting sites crowded on top of the ancient buildings. These protests were followed by more physical bullying and many of the birds would continuously swoop low over the audience, spraying them with guano. It became a characteristic of the performances there and the regular audience members would come prepared with protective clothing!

One year a young bird which had fallen from its nest high on the ruined tower of Peel Cathedral became convinced that Anne, dressed in grey and in role as the harp-playing musician at the side of the performance area, was its mother. It attached itself to Anne’s feet and pecked constantly at her shoes, expecting them to yield pre-digested herring.

“It thinks I’m its mother,” Anne explained to be-mused nearby audience members. When, in spite of the chick’s constant pecking, Anne’s shoes failed to yield food, the chick wandered off through the audience, hopefully pecking at their shoes. It was a difficult situation for the people in the audience who wanted to give food to the chick but knew that only the pre-digested fish was suitable for such a young bird!

A bird also pestered the audience for food at Scotney Castle, Kent, which was beside water, filled with ducks. In 1981, during a performance of Much Ado about Nothing, one of these decided to beg for food from both actors on the stage and members of the audience. Its demands were unrelenting throughout the play, very vocal and focused on the person it was begging from. No shooing away would make it cease as it almost brought the play to a halt. Everyone was laughing at its persistence and boldness, its upstaging of the play equal to that of the peacock at Trevarno.

A mother duck and her ducklings effectively upstaged a performance in The Temple Amphitheatre in the grounds of Chiswick House, London in a performance of The Tempest in 2002. In the centre of the amphitheatre was a pond upon which the duck was happily paddling away with her family. Suddenly she decided that they should all get out of the water and she scrambled up the steep bank of the pond, calling to her ducklings to follow. However the slope was too steep for them and to the distress of the audience, by now ignoring the play, they kept falling back into the pond. The Theatre Set-Up stage manager decided to intervene and provide a ramp for the ducklings to climb. He found one of the company’s sign boards and placed it from the edge of the bank into the water, the mother duck encouraging her family to ascend to safety. This was accomplished, the audience applauded the stage manager and the play continued without further interruptions. From that day onwards the cast understood the true meaning of the term “duck boards”, their use, and their signage boards should the need arise, which could provide a substitute for them.

At Kirby Muxloe Castle, Leicestershire, in 1997, it was the smell of birds which upstaged the play’s performance of Twelfth Night. The wind was blowing the odours from an adjacent nearby poultry farm right across the performance site. However the company manager tried to convince the audience that this was not a bad thing:

“Here we have the perfume “Eau de Poulet”, she announced.

The most positive contribution of birds made to performances of the company’s plays were the demonstrations of falconry at Dilston Hall, given every evening before the beginning of Antony and Cleopatra in 1999. Audiences were delighted at this stunning extra entertainment given by local people as a welcome to Theatre Set-Up newly playing in the grounds of the college to its audiences in Northumberland. The beautiful birds, soaring above the audience against a pale evening sky, gave the actors and the audience a thrill which energised the performance and predisposed the audience to enjoy the play.

SEALS

In another part of the Peel Castle site, surrounded in its St Patrick’s Isle location by water on three sides, at least some of the wildlife appreciated the performances every year. The company always had songs incorporated into the performances, often to provide a costume quick-change bridge for actors between adjacent scenes in which they were playing different characters. The singers naturally needed to “warm up” their voices, and they did this facing the seas behind the castle which flowed between the Isle of Man and Ireland. Seals loved this music and each year they would come up close to the water lapping against the castle to listen to it. “Singing to seals” became an annual feature which the company’s singers looked forward to in the theatre season’s tours.

BATS

Bats sometimes featured in the company’s performances. As bats lived in the rafters of the Medieval Old Hall of Tatton Park, they inevitably became part of the events put on there. The theatre company had to wait for the fire in the middle of the floor to be doused before they could enter the Hall to prepare for the play. In the early days of Theatre Set-Up’s performances there this preparation was necessarily cautious as the custodians had decided to keep the Old Hall in the state of its medieval heyday, unkempt and dirty with straw on the floor.

Long-eared bats lived quietly in their ancient roof home in the hall’s rafters and usually did not interrupt the plays performed there, but during a Theatre Set-Up performance of Cymbeline in 1989 a woman in the audience screamed as a baby bat fell from the rafters onto her feet. With great presence of mind the actor playing Cymbeline bent down, scooped up the bat with a quantity of straw and swept out with it on his exit, placing it in a backstage room in a dark corner until a qualified bat expert should come to return it to the hall where its mother in the rafters could set up a response to the baby’s high echo-location cries and could come down to rescue it. At the end of the performance the woman shrieked again as she noticed flea bites on her shins. She complained bitterly that she had not expected to be attacked by fleas and a bat during the performance of a play.

“You see”, said Anne, “You have been given primary experience of theatre as it used to be in “old-time fleapits” and a very rare familiarity with a bat. You can’t get that in normal theatres.”

In subsequent years the custodians decided to clean up the hall and get rid of the straw and the fleas but the descent of the baby bats continued. The cast then knew what to do for them – just gently scoop them up, put them in a dark corner of the hall and then when everyone had gone, the mother and baby bat would communicate with each other through their echo-location and the mother would come down and take her baby up to the rafters gain. Anne who usually urgently rescued the bats away from the trampling feet of the audience, considered herself privileged to have had that experience, especially as she knew that the need to remove the bats from immediate danger to a place of safety gave her a rare excuse to hold them, as, unless you were a registered bat-expert, handling bats was forbidden.

She remembered the company’s first experience of a baby bat interrupting a performance in the 1979 Twelfth Night in the courtyard of Beningbrough Hall, Yorkshire. Straying from a nearby tree, it fell at the feet of Susannah Best, the actress playing Viola, and it flapped its way backwards and forwards across the stage, blocking her stage moves. She improvised the scene around the bat, pretending that it was part of the scenario until the bat flapped its way off the stage and back under the tree from where it was ultimately rescued by its mother up into the high branches.

CATS

At the beginning of the same season Susannah had experienced difficulties with another creature, a seemingly-very-tame-and obliging cat belonging to another member of the cast and which he had hoped might become a feature of the performances at Forty Hall, Enfield. It seemed a good idea at the time that Susannah as Viola should make her entrance holding this cat in role as the ship’s cat which she had miraculously rescued from the sinking vessel from which she herself had been saved. However in the first rehearsal of this scene the cat would have none of this stage business and shrieking protests and struggling from Susannah’s grasp, ran off into the surrounding undergrowth, her owner in hot pursuit.

Cats of course, know how to become the centre of attention in any event or location. The house cat belonging to Arreton Manor in the Isle of Wight decided to take centre stage in the 1997 performance of Twelfth Night on the lawn there as it demonstrated its prowess in catching a mouse. At last with the stage lighting and public audience happily beyond its previous experience of approval, it flung the mouse up in the air and then down at the actors’ feet in an ecstasy of triumph. It was difficult for the actors to continue with the play until it was persuaded to take the mouse off stage.

The house cat of Kentwell Hall, Suffolk did not need a mouse to attract centre-stage admiration. In a performance of The Winter’s Tale in 2006 it boldly strode into the stage action, sitting between the actors and looking up at them expectantly waiting for attention. Tony Portacio, playing the character, Leontes, could not reasonably ignore this spectacular performance and gestured at the cat in a movement which conveyed the genius of the new cast member’s tactic to upstage the play with such little effort. Only the cat’s owners could persuade the cat to leave the arena so that the play could continue.

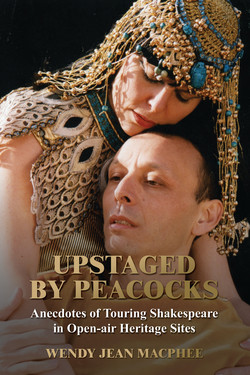

DOGS

Tony Portacio was not so calm in a performance of Antony and Cleopatra in Heathfield Walled Garden in 1999 when a dog appeared from nowhere in the dark night, brushing against Tony as it made its way between two rostra and destroying the illusion that the gap between the rostra represented the space between the area where Tony as Antony lay mortally wounded and the higher monument (on the adjacent rostrum) up to which Cleopatra was trying to have him carried. Tony was wary of dogs at any time and broke character as he started with a fear uncharacteristic of the heroic Antony at this seeming apparition. Evidently the dog belonged to a person normally working on site and it had come through the stage area to find its master who was seated in the audience. Sadly it destroyed the moment in the play when the tenderness between the dying Antony and Cleopatra is most poignant (see the cover photo)!

Theatre Set-Up’s first experience of the capacity of dogs to destroy a moment came at the first site meeting in 1976 on the West Lawn of Forty Hall which was the home venue for the company for 29 years. Hoping to impress the custodian of the site with the quality of some costumes and props that had already been made for the forthcoming production of Hamlet, Anne had arranged them neatly in a pile in the middle of the lawn. Seizing his opportunity to possess these by signing them, Prince, Forty Hall’s resident dog, marched up to the pile, lifted his leg and urinated over it. In spite of this initial mishap he later became an accepted part of the productions at Forty Hall and routinely checked out the performances to make sure that no other dog was trespassing on his patch.

This could have presented problems in the 1977 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream when one of the actors brought in his dog Judy, to be the dog referred to by the character Starveling as partly representing the moon in the play-within-a play of Pyramus and Thisbe. Judy enjoyed the rehearsals for the play enormously and never needing to be taken onstage on a lead, or told when it was time to go on, was always ready for her cue to enter whenever the actor playing Starveling was in the stage action, especially in Act V when she was centre stage, featured as representing the moon. She became very confused, however, at the technical rehearsal when the scenes were “top and tailed”, cutting out any dialogue or stage business irrelevant to technical business or costume changes. Onstage she would go with Starveling and the other actors playing in the scene and no sooner had she settled down to enjoy the scene with them when she was rushed off again and plunged out-of-order into a changed scenario. Once offstage she settled down as usual to rest between her appearances when to her dismay she saw Starveling and the other actors going on stage. Rushing to join them and seeming distressed that she was uncharacteristically missing her usual cues, she made the technical rehearsal, usually a stressful occasion, a cheerful occasion with everyone’s admiration of her professionalism. When the play’s season had finished she was devastated. At the usual time of day when she should be ready to go to Forty Hall for her stage performances she would jump into her master’s car with eager anticipation and could not understand why they were no longer driving off.

Prince got used to her being part of the cast and accepted the inevitability of her continual presence in his domain during the rehearsals and performances of the play. During one performance he came onto the stage where she was part of the stage action and members of the audience froze, expecting him to challenge and fight or even mount her. However he gave her an approved nod which seemed to say, “Oh, she’s just part of this outfit”, and moved off nonchalantly.

Many people took their dogs for walks in the grounds of Forty Hall during the day and early evening during which times Prince was kept inside to prevent incidences with these dogs, but at night he was free to roam and although he was quite small, functioned as a superb security dog. It was only when he and his master were moved from living in Forty Hall that burglaries and vandalism took place there.

Another somewhat larger dog whose function as a guard dog was legendary was the one owned by the custodian of Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire for many years. He kept all the treasures and buildings of the National Trust there intact and continued his unpaid services to the National Trust at Corfe Castle when his master was transferred there as custodian. When Theatre Set-Up performed The Comedy of Errors at Corfe Castle in 1986 the dog had caught burglars trying to rob the National Trust shop there the previous evening. It convinced Anne that often the old ways are best and a dog can sometimes be better security than technical devices.

This was certainly the opinion of the owner of the car parking facility at Penzance where Theatre Set-Up were obliged to leave their van and car before sailing to the Scilly Isles for performances in St Mary’s and Tresco. This dog, a very large German Shepherd dog called Sailor, made sure with his teeth bared and threatening bark that no unauthorised person could enter the enclosed car parking yard or rob any of the vehicles (like Theatre Set-Up’s van) parked just outside it. Over the many years that Theatre Set-Up came to Penzance Anne and this dog became friends and every year when the company came to park their vehicles, Sailor’s owner would release him, much to the horror of the actors who did not know of his special relationship with Anne, and he would greet her as a long-lost friend. However one evening Anne saw him keeping guard in the parking enclosure and expecting a friendly welcome, approached him as usual. Bared teeth, threatening posture and barking made it quite clear that he was then working, that this was not friendly territory and she would be given the same treatment meted out to anyone straying there.

At Plas Newydd in 1981 Anne could not understand why a dog was keeping constant watch outside one of the outer buildings of the mansion. The custodian, on the other hand, was full of admiration for the dog who, he explained, was courting a bitch there.

“Good on you boy”, he called to the dog, “you deserve her”. “And at just the right time”, he said, “She turns her bum.”

There was always a friendly welcome from the house dogs at Pencarrow in Cornwall. In all its printed material Theatre Set-Up always advised its audiences, “Please bring own folding chair or rug”. Anne commented to the dog’s owner that one of the house dogs must have been able to read one of these signs as when she appeared on site this dog brought her a rug in its mouth as if to show that it was ready, like the Pencarrow visitors, to sit in the audience.

“He’s a retriever,” explained the dog’s owner. “He will always welcome you by bringing something to you in his mouth.”

This hospitality, typical of the generosity of the human owners of Pencarrow, became increasingly bizarre as the dog presented Anne with whatever he could find in the house or garden. There were beautiful antique dolls on display in the house and on one occasion the dog appeared with a pair of Victorian doll knickers in its mouth. His presents became even more embarrassingly inappropriate when he appeared at Anne’s music desk with expensive exotic plants between his teeth that he had rifled from the garden pond. His owners always forgave him for whatever wrong he had done, as he was a very affectionate dog with what seemed to be a permanent smile on his face.

A large beagle dog with floppy ears called Harold rejoiced at the chance a Theatre Set-Up performance in the Temple Amphitheatre, Chiswick in 2005, gave him to achieve an ambition to jump into its central pond. Evidently he had been taken for his daily walk past the amphitheatre and had looked longingly at the pond, prevented by going into it for an enjoyable swim by the fence which surrounded the site. On this occasion the gate in the fence was open to allow the audience to enter, and taking his chance, Harold escaped from his owner who frantically called out to him as he raced through the gate and bounded down the terraced slopes of the amphitheatre, his ears flapping wildly, at last plunging into the pond and swimming around it in delight. It took some time for his embarrassed owner to persuade him to come out of the pond and to succumb to being put on a lead for an exit through the amused audience settling down to eat their picnics before the play began.

A reference to a dog far from the scene of the performances caused a hiatus in the performance of Romeo and Juliet in 1996. The actress performing Juliet, Victoria Stillwell, loved dogs, later abandoning her acting career for one specialising in dog behaviour, presented on television in the UK and the USA under the title of “It’s Me or the Dog”. Anne was performing her favourite stage role of the Nurse in the play and was waiting offstage for her cue to enter into the play’s action when she began to tell Victoria about the games she enjoyed playing with Oscar, the much-loved dog which lived downstairs with her neighbours. Both she and Victoria became so engrossed with this description that Anne missed her cue and was astonished to be hauled by her arm onto the stage by the actor also directing the play that year. Considerable bruising on her arm reminded her of the occasion and her need to prioritise the stage action rather than remembering the beloved Oscar.

Sometimes dogs in the Theatre Set-Up performance sites were an integral part of the house arrangements. Muffin, a tiny dog at Kentwell Hall, Suffolk was one of these. At the site visit during which Anne and the property’s owner were deciding on the location of the play, they chose a bank beside the Hall’s moat. The plan was that the audience would sit on the opposite bank which slanted down to the moat, providing a tiered effect in rows of chairs one above the other. Muffin seemed to question the wisdom of this as she stood sideways on the audience bank with a quizzical look at her owner. In spite of her disapproval of this arrangement, the performance went ahead in this location, but the back legs of the audience chairs had to be fixed into the bank. This was fine when rain had made the bank soft, but dry hard conditions made this impossible and endorsed Muffin’s criticism as the audience tried not to be tipped forward into the moat on their sloping chairs.

The dog with the most site responsibility was Topsy of the Baroniet of Rosendal, Norway. She welcomed in all the hundreds of visitors who came to her resplendent home and was in charge of general security. She became very disturbed during a 1996 rehearsal in the Baroniet courtyard of the duel between the actors performing the characters of Tybalt and Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet.

“Fighting in my courtyard?” she seemed to be exclaiming. “Which of these is the guilty cause of it?”

She watched for a short while and then, taking her decision, bounded reprovingly over to the actor playing Tybalt, the belligerent character in the play. Such accurate discrimination complemented not only her ability to detect Tybalt’s aggression, but the actor’s intention and portrayal of this characteristic of the role.

In Cornwall people were often given permission to bring their dogs to the performances. At one of the performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1995 in Trevarno there were 13 dogs of varied species in the audience. The actor performing Puck made a sudden loud entrance onto the stage and all the 13 dogs barked their alarm in a cacophony of tones. It was a good moment in the play, heightening Puck’s supposed supernatural presence!

In 2011, much to the amazement of the local animals who had become accustomed to the peace of a semi-wild garden haven, permission was given to the company to rehearse the play in a rear extension of a suburban garden which backed onto a park and would not thus disturb any neighbours. Foremost of these animals was Duke, a huge Great Dane dog whose fenced garden adjoined the rehearsal area. He had made acquaintance with members of the company while taking his master for a walk in the nearby street and had enjoyed their admiring attention. When their rehearsals began he had no intention of allowing that to cease as he thrust his head above the fence of his home waiting for the expected patting of his head to occur. Of course the cast did not want him to feel rejected and the appearance of his head above the fence always created a break in the rehearsal schedule.

The dog who belonged to the owners of the rehearsal space was Otto, a lively dachshund. One of the company’s cast members owned the house and garden next door and had always had problems keeping Otto out of his garden into which he could wriggle through gaps in the dividing hedge. You can imagine Otto’s indignation when he saw this neighbour delivering his spoken lines and being put through his paces in the play in what Otto considered to be his own territory. He stood looking at the actor in dumbfounded disbelief at the outrageous cheek of it!

Other creatures, accustomed to being able to wander freely through the rehearsal space, watched the unfolding of the play with astonishment. A neighbouring cat took advantage of the roof of a shed at the edge of the garden area to survey the extraordinary proceedings in the style of an attentive member of a theatre audience in the dress circle. This was at an advanced stage in the rehearsal schedule and the cat obviously could not understand the formality of the action, lacking the spontaneity of the human behaviour usually manifest in this spot!

SHEEP

Many of the beautiful sites where Theatre Set-Up’s performances were held were surrounded by grazing sheep. These contributed to the pastoral reality of performances of As You Like It in Bowhill, Scotland. During any scenes involving the characters of the shepherds in the play the actors offstage used to enjoy making sheep noises. These were so realistic at Bowhill that the sheep in an adjacent field responded loudly and ran towards the tents to recover which of their flock they assumed had strayed there.

FISH

A fish made a surprise appearance at the performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1983 at Sudeley Castle. The actor performing Starveling as the Pyramus and Thisbe play’s character of the moon had a carved flat wooden dog representing the moon which he usually flung away sulkily at the interruption of his performance by the characters playing the courtiers. On this occasion, aware that the wooden dog would float, he flung it into the pond. This startled one of the carp there which leapt into the air in protest, giving the audience a rare performance of the play involving a leaping fish.

HORSES

Horses from another event being presented at Carisbrooke Castle, Isle of Wight, gave one of the performances there considerable problems. Unfortunately the entrance of the company’s vehicles clashed with the exit of the horses and the gear they were pulling. The nature of the terrain made it difficult for either side to back off and after the vehicles were driven to one side the horses struggled past. The next day the owners of the horses were so angered by the incident that they piled their rubbish by the theatre company’s changing tents, an action which the company, given the strength of the horses, wisely chose to ignore.

A FOX

The actress performing in the 1995 performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream wore a long curly red wig for the role of Hippolyta which she put with her costume in the off-stage right changing area of an open air performance of the play at Wollaton Hall, Nottingham. When she came to change into it she was alarmed to see a fox racing off into the distance, the red wig in its mouth. Evidently the fox had mistaken it for one of its cubs. She later complained:

“It is a dreadful thing to see the wig which transforms your character being carted off by a fox!”

A STUFFED GIRAFFE

Wollaton Hall provided the play and its audience with an indoor alternative venue in its hall should the weather be stormy. In the early days of performances there the space where the play could be performed was set out as a museum of stuffed exotic animals. Most of these were in glass cases, glaring with artificial eyes at both the actors and the audiences, but the huge giraffe stood proudly at the back of the audience area with some seating beneath it. Children were especially astonished at the size of its masculine glory when they looked up at it during the performance!

INSECTS

Any outdoor venue is likely to run the gauntlet of insects which plague both members of the audience and the actors. Theatre Set-Up discovered that the insects in Northumberland, Yorkshire and Cornwall were far more robust and numerous than in any other county. Over the years, strategies had to be developed to cope with this. Any exposed flesh of the actors (as well as the tights-clad legs of male actors) always needed to be sprayed with insect-repellent, and mosquito coils were always lit beside the changing tents to the sides of the stage and often interspersed with the sun-floods lighting placed in an arc at the front of the stage area. On one occasion when Anne was commuting between her teaching job in London and performances in the grounds of Wallington Hall, Northumberland, she arrived ready to change into costume and do her stage make-up minutes before the start of the play. She was hit by a wall of insects as she rushed to the changing area.

“Quick, everybody,” she shouted to the cast, “Do as I am doing. Put on loads of insect-repellent to see if that will help!”

However such was the density of the insect hoards that even that was insufficient, as the insects went into the open eyes of the actors and into their mouths as soon as they opened them to deliver their lines! When Anne suggested to the gardeners of the venue that the site of the play should be sprayed to kill any insects, they were most offended:

“The insects live here. They were here first. You are only visitors!”

Anne adopted a strategy to help members of the audience in insect-plagued venues. This was necessary not only to protect them from irritation and possible bites from the insects, but to stop them twitching and flicking them away during the performances. This constant movement would be a distraction for both people in the audience and the actors. Therefore before performances guaranteed to be insect-bound, Anne would go around the audience offering to put insect repellent on the hands of anyone who had not provided themselves with their own repellent and then they could apply it themselves to any exposed flesh, plus over their hair, into which insects loved to nestle! This usually worked but sometimes an extra application had to be made in the interval before the second half of the play. Insect repellent became a very essential part of the company’s gear!

In the early days of the company’s tours the primitive sun-floods which lit the play in an arc around the stage area were not glass-fronted, and insects, attracted to the light-bulbs, would be burnt by them, sending smoke rising as if in their funeral pyres. On one occasion the smell of this smoke alarmed the company’s patron during a performance in his garden on Tresco, as his property on the mainland had recently been largely burnt down and he rushed to the scene to see if another fire had also been ignited, this time in his island home.

On the Isle of Wight, sensitive local residents were more concerned about the cruel fate of the insects themselves:

“Please can you get sun-floods with glass on the front to protect the insects. We can’t stand seeing them burn to their deaths during the play and cannot come to performances again if this continues.”

Fortunately it was possible to replace the old sun-floods with new glass-fronted ones and everyone was happier.

However some actors (like the residents of the Isle of Wight) became upset by any of the operations of the company causing the accidental deaths of insects and they were distressed by the deaths of insects who crashed into the windscreens of the travelling vehicles. It was a company rule that, with the exception of touring to venues many miles apart, the company vehicles should not travel very fast. Thus generally any insects accidentally landing on the windscreens had time to escape from them.

In some areas, however, where many animals were in fields beside the roads on which the company was travelling, there were so many insects in the surrounding air that many met a sad fate on the windscreens. The car carrying three actors always followed the van (a customised white Mercedes Benz high-top van) fairly closely so that the company was travelling in a safe convoy. On one of the occasions when suicidal insects on the windscreen were distressing actors in the car, the actor who was driving the car decided to create a diversion by singing the main songs from “Half a Sixpence,” the musical he had recently been performing in. He was an excellent singer and soon all the actors in the car joined in singing with him. Soon this impromptu performance became the main focus of attention in the car and the task of following the company van was neglected. After a while someone in the car noticed that the route the car was following was not the one leading to the venue where the performance would be held that evening.

“Oh, where are we?” the driver cried, “I’ve been religiously following the company van.”

Looking at the white van in front of the car more closely, everyone in the car shouted out:

“You’ve been following the wrong white van!”

So in future journeys in which many insects performed death crashes onto the car’s windscreen, sung diversions were monitored by the car’s passengers to ensure that the insects’ accidental self-sacrifices were not revenged by their souls causing the car driver to lose sight of the lead vehicle, and steps were taken to ensure that right white van was followed!