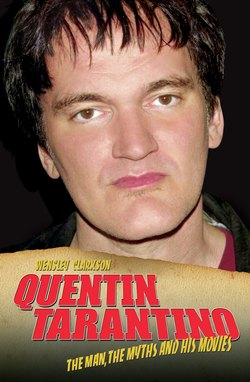

Читать книгу Quentin Tarantino - The Man, The Myths and the Movies - Wensley Clarkson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION – THE PATH OF A RIGHTEOUS MAN

ОглавлениеReader beware. This is a book about a Hollywood icon who has never shied away from speaking his mind. It does not reveal all of Quentin Tarantino’s most secret or outrageous thoughts but it is the most fascinating account of his life you are ever likely to read.

Who is the man behind the public face of the world’s premier movie-maker? Whence comes his love of life’s darkness, his apocalyptic drive? How is it possible for someone with so little formal education to become the ultimate 21st-century artist?

I first came across Quentin Tarantino when we were both struggling scriptwriters in Los Angeles in early 1991. My agent suggested I read a ‘really wacky’ screenplay entitled Reservoir Dogs because she reckoned it was one of the funkiest scripts she had ever come across. I read it from cover to cover in one sitting. No one had bought it at that stage, but I knew it would only be a matter of time before its author became a force to be reckoned with.

I later encountered Quentin at a horror festival in a convention centre near Los Angeles airport, not far from where, as a teenager, he had been woken by the constant thunder of jets taking off and landing. I got a feeling for my subject by watching the way he performed in front of hundreds of adoring fellow movie geeks. He worked the crowd brilliantly.

I also consulted the person who knows Quentin best – his mother Connie Zastoupil. ‘He’s riding on the crest of a wave,’ she declared. ‘But I’m worried that he is going too fast.’

For the sake of this book, Connie agreed to open up old wounds and disclose the life she has shared with her only child. I spent many hours interviewing her, finding out about Quentin’s strange habits as a child and their occasionally volatile relationship. She told me that in her opinion this book was going to be the only truthful and balanced account of her son’s life. She said she was sure Quentin would ‘appreciate that you are trying to get it right’. Her decision to sanction my efforts above all other books on Quentin deserves my most heartfelt thanks. Much of the early part of this book reflects her courage and determination in bringing up a child as a single parent.

My other vital source were Quentin’s brilliant screenplays. They tell so much of his life that they provided the thread I needed to sew the narrative together. Quentin’s life is his movies and his movies give us a glimpse of his life.

When we last met, Quentin was quick-witted and sharp as ever, giving the answers to questions almost before I’d asked them. I greatly appreciate that he did not try and block my efforts to write this book. Although he never came on board officially, he never stood in the way of any of his friends when they decided to help me. I think the book is better as a result. With their generous contributions, a picture with words has emerged that fully conveys the unique stature of the man.

Quentin is the first movie director in Hollywood history to be treated like a rock star. Screaming adolescent girls – not legally old enough to see his films – mob him everywhere. Even the late, great rock icon Kurt Cobain thanked Quentin Tarantino on the album In Utero, following the release of Reservoir Dogs.

The celebrated hamburger exchange in Pulp Fiction is one of his trademark scenes – a gangster delivering a lecture on an arcane aspect of popular culture. The characters discuss the question of what a McDonald’s quarterpounder hamburger is called in France. The answer is a ‘Royale’ because, as all Tarantino fans know, France follows the metric system. The way things are going, a Paris quarterpounder will soon be officially renamed a ‘Tarantino’.

There is no simple way to explain this worldwide mania. Perhaps as in Pulp Fiction, the question is best explored from different points of view.

In the past only one young director has generated so much fuss on such a limited output – and that was Orson Welles. Some even suggest that Reservoir Dogs is another Citizen Kane. Both are all-time great films but other factors must surely be involved.

In general, the surest way for an artist to achieve adulation and visibility beyond the limits of their chosen discipline is to have extraordinary sexual charisma. Youth and an air of danger will, if the artist is lucky, invite comparison with rock stars. Brett Easton Ellis and Damien Hirst are obvious examples from the worlds of literature and art.

Yet Ellis and Hirst are never actually mobbed by screaming teenage girls, whereas Quentin Tarantino has been. Youth is certainly part of his mystique – he was only 28 when he made Reservoir Dogs – but there is far more to it than that.

Unlike Scorsese, Coppola and Spielberg, Quentin has achieved his amazing success in a frighteningly short time. Also unlike them he has yet to make a flop. To date, his oeuvre includes Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction (which he created and directed), Jackie Brown and Kill Bill plus True Romance and Natural Born Killers (written by him but directed by others).

Yet Quentin is the sort of guy who, before 1992 – when Reservoir Dogs put his geeky face on the cover of every magazine in Christendom – would probably have gone unnoticed in any gathering of more than two people. That is part of his appeal. Quentin may be God to his more extravagant fans, but he is also Everyman.

Young audiences lap up everything he has to offer. Many of them would no doubt love to write like him (hence the extraordinary success of his published screenplays).

Quentin’s tours of Britain, to promote those screenplays, are always sold out. His scripts have been bought by more than 200,000 people in Britain alone, even though paperback screenplays usually only sell to passionate film buffs and would-be scriptwriters.

His astonishing success may be at least partly due to his unusual name. Quentin Tarantino sounds half English aristocrat, half Italian-American. (He is actually half Italian, a quarter Cherokee and a quarter Irish.) Yet, however much Tarantino may sound like a brand name, his films definitely have a style all their own. Woody Allen is probably the only other director whose work is so easily identifiable.

Despite what his detractors say, there is a great deal more to Quentin than diligence, a solid grounding in movie culture and a knack for exploiting this generation’s insatiable appetite for sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll and startling violence. His use of violence is actually the most commonly misunderstood aspect of Quentin’s work. His average body count is, in fact, much lower than in most Schwarzenegger movies. More importantly, his approach to violence is invariably more subtle than his critics are prepared to admit.

His skill lies in coaxing the audience into thinking they are seeing gruesome violence without it happening on screen. A true cineaste, his control of the viewers’ imagination conjures up infinitely more terrible scenes than anything the camera can show them.

Quentin’s work as a director and screenwriter is all cut – or rather, hacked – from the same cloth. Combining the offbeat humour of seemingly irrelevant dialogue with designer violence is the gimmick that has raised his profile so far so fast.

Tarantino gags are appearing everywhere, from Steve Bell’s If… cartoon strip for the Guardian to Garry Bushell’s TV column in the Sun, where the writer assumed that his millions of readers would understand a joke about tempestuous soccer star Eric Cantona signing to appear in ‘the new Tarantino movie, Reservoir Frogs’.

Then there is the fact that Quentin – unlike many other so-called legendary Hollywood directors – has insisted on working with his own screenplays. This gives his movies a strong visual character. He believes that directing ‘other people’s material puts you in handcuffs’. Acting in such movies is fine but directing them is an entirely different matter.

Tarantino’s scripts have a way of reworking classic genres. The plots and characters are familiar, but Quentin’s structure and dialogue transcend category. His style is firmly rooted in a world of 1970s cool-guy pop culture that may never have existed except in movies, but resurfaced in the 1990s.

Although it is his distinct pure blend of comedy and violence that appeals to critics and cinephiles, it is probably the violence that accounts for Quentin’s status as a youth icon. There is a sense of danger in his work. His films have in many ways been treated like a banned substance: Reservoir Dogs waited more than two years to get a video release in Britain and there was much debate about whether Natural Born Killers would be allowed cinema exhibition in the same country. This outlaw status is a crucial part of the Tarantino myth. What troubles critics about his work – his lack of moral perspective – is precisely what most appeals to his young fans.

Although in person, Tarantino may resemble a harmless trainspotter, it is the blank-eyed violence of his movies, their callous laughter at the dark, that has made him Hollywood’s first rock star director. Yet he has remained approachable and exudes the easy charm of one completely unaware of his status as the world’s hottest film director. It is as if he’s saying, if I can do it, so can you…