Читать книгу Dwellers in the House of the Lord - Wesley McNair - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

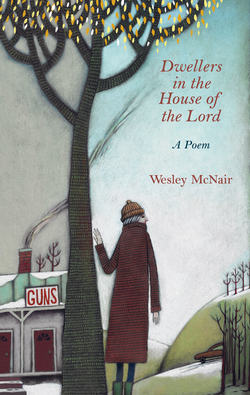

Оглавление1 •

Inside the box she sent is bubble wrap

folded over and over around

a thick envelope, awkwardly folded,

and deeper down, wrapped

in Christmas paper with my name

on top in a blur of letters

handwritten over and over,

my younger sister Aimee’s late gift,

sealed in an old plastic bag

like a secret she wants only me

to know: a silver charm bracelet,

which in the winter light of my kitchen,

dangles a palace, a running horse,

a heart with a key, and a clock.

Once, after returning from a long visit

with our mother, Aimee, married

with two daughters, hid under her bed,

keeping herself a secret. Mike searched

and called for hours before she called back

at last and he found her, discovering also

his unshakable, lifelong anger at the woman

my sister had tried to put out of her mind.

But Mike was her replacement

for my mother.

A mind has so much to keep track of:

which secrets to share,

which to guard from others,

and now, who and where anyone

is anymore. In Aimee’s letter—

creased and re-creased from

her underlining and afterthoughts

in the margins—she asks me to mail

her Christmas cards for my children,

having forgotten their addresses

and their names. They can’t hear

my chattering, she writes,

but can read of several things

I wanted to write inside the card itself.

The Lord loves you, she remembers

on the back, where a single heart

floats in a blank sky.

2 •

In the famous family photograph,

Aimee sits on the couch beside Mike

in his Navy uniform, holding his hand

and looking up at him with the defenseless

wonder she wore all though girlhood.

Eight years old, she has just asked him

to marry her. Nobody would have guessed

he would come back later to do it,

or that he would take her to live with him

north of a Navy base in rural Virginia,

his smiling, clean-shaven face now

overgrown by an unkempt, anti-social beard.

Outside the back window

of Aimee’s second house

from the time they moved in,

the high, dangling chains

and gambrel stick

of a deer-slaughtering station.

In the front, open all day,

Mike’s gun shop. “Obama

is going to make me rich,”

he says one night, chuckling

on the phone before handing it

to Aimee, “but I’m already

out of bullets. Everybody

down here’s out of bullets.”

Behind his chain-link fence, two dogs,

penned for life without names

so they won’t be spoiled for hunting.

3 •

One fall day in Claremont, New Hampshire,

my stepfather, who came with his family

from Quebec, Canada, took me and my brothers

to visit a Polish family in a triple-decker

apartment without enough windows to throw

off the gloom. The father produced two glasses

for drink, and at the edges of his storytelling

and gesticulation, Mike, a quiet boy my older

brother’s age, emerged beside his mother,

who dragged one leg, because of a stroke

she suffered as a young woman, I later learned,

and still later, from Mike, that she never

touched him except with a switch,

yelling at him in Polish for breaking her rules,

and each week made him bring her, as if

it were his fault, the half-empty bottles of vodka

his father had hidden in the hall closet, or behind

the toilet, or under the front seat of the car.

It took only ten years for the new K-Mart Lawn

and Garden Center at the mall off route 89 to destroy

the nursery business my stepfather and my mother

had built. Afterward he lost the anger he learned

from growing up as an immigrant, and the defensive

tilt of his chin that said I’m better than you

and I’m no good at the same time. Opening himself

at last to the defeat he feared from the start,

he went back to his job on the night shift

at the same shop where his father worked

until he died. No one could reach him. Even when

my mother, grown desperate, blamed him for quitting,

he was silent, wearing the dazed look of a man

who’d awakened in the dreamlife of a stranger.

“Listen to her brag about getting food stamps,”

Mike shouts to Aimee, who’s in the kitchen

while he watches a black woman

with two children in Virginia Beach on TV.

“She can’t even talk right,” he says.

In the presidential campaign of 2016,

two stories: on one side, the uplifting

American Story of the Immigrant,

on the other, a darker story

derived from the failures of the first,

both of them our stories.

4 •

For years the two of them drifted

toward each other, Mike dulled

by alcohol on submarines, Aimee

looking for a home. At age 21,

she ended up in a bathtub

in the projects of Claremont

with a French-Canadian husband

who stooped over her, starting up

a hair dryer and threatening

to toss it into the water with her.

Meanwhile, at 35, Mike spent

an entire leave and all his money

on a bar stool in Naples, Italy,

barely recalling his wife and stepchildren

back in the States. Closer now

in their drift, Mike, retired from the Navy,

wakes up in Abner, Virginia, as a Jehovah’s

Witness with half his life gone to drink,

saved by Alcoholics Anonymous

and an angry God devoted to fire

and retribution. Divorced, like him,

Aimee is back home with her father,

who named her, now an old man gone silent,

and her pitiless, faultfinding mother,

more convinced than ever that the only

life left for her is her reconstructed

daughter’s life. Driving to another town,

Aimee walks up four stairways of a tall

building and jumps off the roof, breaking

her ankle, her leg, and two vertebrae.

Waking in the trash of an alley, she feels

the excruciating pain of her body,

which is also the pain of still being alive.

This is the moment my fragile sister thinks of,

lying in the dark for hours under her bed

after returning to Mike from her mother’s house,

with no place else on earth to hide.

5 •

But before that lying in the dark,

she must lie in the zero

of a white room at the hospital,

bandaged and lost to herself.

And when at last she opens

her eyes, she finds Mike sitting

beside her, and sitting there

again the next day, just as he sat

when she was a child wishing

he would take her far away,

and after she reaches out to hold

his hand, and they go on talking

over weeks in their low, intimate way,

sometimes kissing, it becomes clear