Читать книгу Modern Alchemy and the Philosopher's Stone - Wilfried B. Holzapfel - Страница 33

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

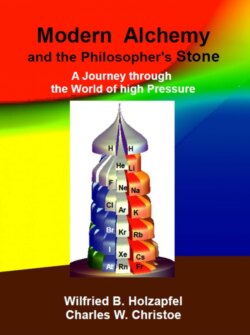

ОглавлениеAt the sides of his figure he had included the perceptions of Aristotle: cold-hot and wet-dry. The arrow from cold to hot pointed in the direction of increasing temperature. He explained that in his figure the arrow from wet to dry represented more of an increase in the density of the substance than it did actual moisture content.

“So here’s the thing,” he explained carefully. “I consider an increase in density to be equivalent to an increase of pressure within the substance. Of course, the ancients recognized, as we do, that some substances naturally have more mass per unit volume than do others. And that concept still fits both the modern and the historic views of this diagram. But it fits especially well with my work to take pressure as the horizontal axis. That way I am able to include changes of density within a single substance that are due to an externally applied pressure.

“You see, we can change the nature of a substance by heating it or by applying external pressure, or both at the same time! It is in that sense that the modern alchemist follows the practices handed down to him through the ages. It’s just that, in my case, we go to greater extremes in these dimensions from very cold to very hot and from partial vacuum to thousands of atmospheres of pressure.

“The other thing we do differently these days is that we make precise measurements using modern techniques and instrumentation. We also communicate our results openly using agreed-upon units of measurement and standard terminology. These more modern practices were introduced into the study of natural sciences at the time of Galileo Galilei around 1600 AD. Galileo should have said that we should measure everything that we can measure and what we cannot measure, we should make measurable.”

“So, if I follow you correctly,” Helen interjected, “you are saying that Galileo ushered in a whole new era of scientific observation and reporting.”

“That is exactly what I mean,” the professor responded. “And that is why most scientists today consider Galileo to be the father of modern science.”

“But you still think of yourself as somewhat of an alchemist, right?”

“I do,” agreed the professor. “And I hope that I can explain that more fully to you and Marie. But first, let me ask you what might be missing in this picture.”

“I remember that when we first discussed the figure with the triangles (Figure 4), the four regions of this diagram appeared at the corners, but there was one in the center that you described as representing the Materia Prima,” Helen said. “I think that you said that the middle symbol corresponded to a superposition of the other four – or maybe that the other four had been derived from the central figure. Then, when we were discussing the diagram from Basil Valentine (Figure 5), you said something like ‘Out of formless matter, the universe became organized into four basic elements.’ So what seems to be missing from this diagram is a region corresponding to the original heavenly matter of the Confusum Chaos.”

“Very good!” exclaimed the professor. “What also does not appear in this chart is a fifth element, a fifth essence, the quinta essencia in Latin.”

“Oh, so that is where we get the adjective ‘quintessential’ to describe the most fundamental example of something, as in ‘the quintessential question is ….,” Marie chimed in.

“Indeed so,” the professor continued. “Aristotle envisioned the quintessence as an eternal unchangeable agent, like an ether, that would fill the whole world. Other alchemists preferred to think of the quintessence as an actual primary substance, or a Materia Prima, you might say, from which the other four could be derived. So perhaps the ‘quintessential question’ for us today, Marie, is ‘what is really the fifth essence and how would we describe it today?”

“I was just thinking of asking you that question,” Helen said to the professor. “Very well,” replied the professor. “Let’s see what I can do with it.

“It is not a particularly easy question to answer. The early books that have been written about alchemy tended to be fanciful stories about alchemists that were not written by the alchemists themselves. A modern example of that might be the Harry Potter novels. These popular – and profitable – tales focus on the unexplained magic that has been associated with alchemy rather than reporting on the actual work that the practitioners of alchemy did or the things that they accomplished. Even if the names of the alchemists were not fictitious, the early writers wove many legends around a few sparse facts. Throughout history, it seems, such legends have sold much better than books about pure facts! As a result, the various stories about the great Arab scientists Gabir and Avicenna reflect more fantasy than fact. Who could translate the scientific-philosophical books from Arabic to the western Latin without distorting the content a little here and there along the long journey to our world? So many legends have been added to the lives of the alchemists that what we have now are mostly just fairy tales. What happened to Dr. Faust in Goethe's play?”

Helen was more familiar with Gounod’s opera than with the actual play from which it was loosely derived, but she assumed the lesson was more-or-less the same: Don’t make a deal with the Devil to find pleasure by acquiring knowledge of the world. Yet here was Professor Wood offering to explain the secrets of the alchemists to her. She shuddered at the analogy as the professor continued his explanation.

“I’ll try to present a more complete picture of the way in which these early scientists and philosophers laid the foundation for today's science. Remember that the word alchimia came from contacts with the Arabs during the early medieval times when traders on the Silk Road then, later, Christian Crusaders entered the Arab-Islamic world. In those days, only the monasteries cared much about science. Even among the nobility, independent research was practically inconceivable. At that time, the church had the truth and it determined what the acceptable view of the world was. Independent thinkers who read the banned books of ‘satanic’ Arabs had to worry about being condemned as heretics. Accordingly, the alchemists could only discuss their work in more or less secret circles and they had to include Christian symbols in their writings. God, the sole creator of the universe, must have given the Philosopher's Stone its power. Otherwise, the stone and all the associated alchemy would clearly have been the devil's work.

“Oriental medical knowledge was also suspicious. Inevitably, the image of the alchemist was strongly influenced by the church and orthodox Christianity. It was not until the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment that independent research even became possible. Even then Galileo was condemned for the dissemination of his conviction! If you're splitting hairs, Galileo was convicted because he claimed to know the truth! The truth was supposed to be a matter of faith about which the Church was the final authority. Scientists today are more modest. They only speak of knowledge. By convention, knowledge can change over time and the discoveries of the scientists are no longer controlled by the Catholic Church.

“Nonetheless, the gloomy view of the alchemists as mere magicians persists to the present day. Of course, we still see a lot of fundamentalism in politics, and even commerce, today. Take, for instance, the work of Charles Darwin regarding the evolution of species! In scientific circles Darwin’s observations are considered to be confirmed by a large number of individual findings. But there are still many fundamental - it's that believe that the divine creation of various creatures and humans can be proven by quotations from the Bible. These people end up discarding all scientific evidence to the contrary. So, if you think about it, the alchemists were only scientists who were downgraded in their time because of the independence of their thinking and research. They looked ‘outside the box’ beyond the narrow confines of the Catholic world and, as a result, came into conflict with the powers of the Church and its indoctrinated population of the time.

“It is not surprising that this branding of the alchemists persisted until the Age of Enlightenment. Finally, people no longer spoke of researchers and scientific thinkers as alchemists but as humanists, polymaths or naturalists. Despite all that, a genuine rehabilitation of the alchemists themselves is still pending!”

Marie had become a little fidgety with all this talk of the alchemists. “But didn’t you want to explain the quintessence?” she asked as politely as she could.

“Oh yes, I’m sorry about that,” the professor answered. “I know that I get a little carried away sometimes, but it is hard to understand the concept of quintessence without a little insight into the historic world of alchemy. Now let me describe the underpinnings of modern alchemy, as I view it.”