Читать книгу The Silence of the Spirits - Wilfried N'Sondé - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

Оглавление“The Silence of the Spirits: From Civil Conflict to the War of Identities”

Meeting is only the beginning of separation.

Japanese Buddhist proverb

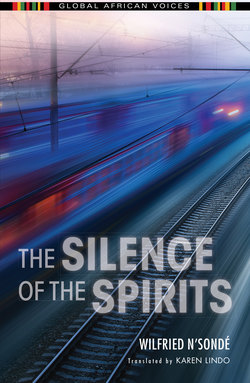

Following Le cœur des enfants léopards (2007), published in the Global African Voices series as The Heart of the Leopard Children in 2016, The Silence of the Spirits, initially published in French as Le silence des esprits in 2010, is Wilfried N’Sondé’s second novel. Born in Brazzaville in the Republic of the Congo, N’Sondé grew up in France. His work examines various facets of the postcolonial condition, the tenuous relationship between Africa and Europe, the post-migratory experience, and the challenges of belonging and integration. However, the pioneering spirit of his work stands out when he turns his attention to the multiple ways in which individuals negotiate identities and relationships in France, a country that has attempted to foreclose the colonial past without fully thinking it through or for that matter finding a path to addressing this historical legacy and its multicultural realities. As N’Sondé has claimed, the result has been the inevitable introduction of “questionable criteria in order to divide and categorize, driving us gradually further away from the essence of being and magic of words.”1 This unwillingness to consider how the past ultimately continues to shape the future has introduced an awkward silence, one that is “not silence as in secret,” as Srilata Ravi has shown, “but silence as in language, . . . and as such becomes the shared space where cosmopolitanism as intelligence, curiosity and a challenge can operate. As both reason and affect, N’Sondé’s silence as communion is a metaphor for the practice of conversation, one that does not define itself as failed or completed. Cosmopolitanism as conversation does not end—hence it poses the challenge of continued engagement.”2

Even though the French Republic remains “one and indivisible” as enshrined in the first constitution of 1791, a principle that underscores the commitment to protecting the rights of all citizens regardless of ethnicity, religion, or other social associations, the fact remains that the equality of citizens simply does not exist. To this end, N’Sondé’s own background has always meant, even though in principle this should not be a factor, that, “depending on the context,” as Myriam Louviot has observed, “the author is considered either African or French, a spokesperson of sorts on issues of diversity.”3 Not surprisingly, N’Sondé has himself repeatedly commented on this question: “What is the point of me getting hoarse from explaining who I am or who I would like to be? There is nothing I can do. My thoughts are being kept in check. My words have no meaning. They believe they have summarized my ideas intelligently by reducing me to a series of nostalgic and exotic images, filled with a mixture of compassion and guilt, all well-intentioned. A romantic sketch, inherited from colonial haze and archaic prejudices.”4 How then has a novel such as The Silence of the Spirits been able to simultaneously explore such complex twenty-first-century issues while also advancing the conversation in meaningful ways?

After a long day at a Paris hospital where she works as a nurse’s aid, Christelle finally heads home on the regional commuter train. Daydreaming, dozing off, this young French woman’s focus eventually settles on the passenger facing her, a young man named Clovis Nzila. He is clearly distressed, out of place, and the reader learns that he is in fact a former African child soldier who has ended up in France as a sans-papiers, an illegal, undocumented migrant. As French psychoanalyst Charles Baudoin once wrote, “Nothing predisposes to fear like the conviction that we shall be afraid, and, above all, the conviction that we shall be afraid in certain specific conditions.”5 Somewhat unexpectedly then, Christelle reaches out to him, and these two passengers who otherwise might never have met find themselves on the same train, in a space in which time is temporarily interrupted, suspended long enough for a metaphorical and physical journey of discovery toward the other to begin.

On the surface, they have little in common, but N’Sondé gradually discloses information about them that will provide the coordinates of their relationship, the circumstances in which discovery and openness to the other becomes conceivable. “Like mine,” Nzila realizes, “her heart had been broken during her childhood, a nightmare that haunts her and works on her behind her veil of oblivion even to this day. The shadows of her stepfather’s hands and gaze on her bare thighs. All the years of feeling defiled. A bitter wound in her stomach, a hideous scar covering the memory of it all.” We learn that, now living alone in a small apartment, she was molested as a child and was later the victim of domestic abuse at the hands of an alcoholic husband. As for Nzila, “Every day, I kept a low profile in Paris, walking with my head down and staring at my feet to avoid looking in front of me. I’d forgotten all about the dream, which risked ending up in bureaucracy, a file with some numbers stamped on it. I was running away, heading nowhere, to avoid being detained, enclosed behind bars, with wrists and ankles handcuffed, accused of having tried everything, defied every unimaginable danger, flirted with death a thousand times, suffered everyone’s contempt, and all I wanted was simply to live!” A shared history of violence brings them together, but their hybridity threatens the social order, the monolithism of a society in which difference has no place, yet in which those very differences structure and define social relations. In her professional environment, Christelle “was about making others happy,” and rather than be governed by fear, her impulse is instead to humanize those whose paths (it is worth noting that in Kikongo, for example, nzila means a passage, a path or a way) she crosses: “She’d forgotten her own worries, escaped from her own labyrinth of anxi eties and boredom to take care of me, an illegal immigrant, far more destitute than she.”

Christelle’s decision to extend a helping hand to Nzila, to provide him with a place to stay, a shelter, serves to address broader societal circumstances. In 2009, and therefore at the time of writing The Silence of the Spirits, the question of providing assistance to sans-papiers and refugees was being reviewed in the French parliament and was a hotly debated and divisive issue. Already back in 2003, several campaigns had been launched against laws that defined the degree to which individuals, associations, or organizations could provide assistance or help to illegal or undocumented foreigners, according to which “anyone who, directly or indirectly, helps, facilitates or tries to facilitate the entry, the circulation or the unlawful residence of a foreigner in France” could be subject to prosecution. Thus, in the face of increased government control and restrictions over immigration and the accompanying debasing and dehumanizing logic shaping such initiatives and measures, a term was adopted to designate those attempts at criminalizing such efforts, namely a délit d’hospitalité, or “offense of solidarity.” N’Sondé’s staging of hospitality, of the precarious position in which such choices place citizens, and the criminalizing of the implied intimacy, therefore shapes much of the narrative.

In the eighteenth century, in the famous Encyclopédie, one could read under the entry for “hospitality” that “I define this virtue as a liberality exercised towards foreigners, especially if one receives them into one’s home: the just measure of this type of beneficence depends on what contributes the most to the great end that men must have as a goal, namely reciprocal help, fidelity, exchange between various states, concord, and the duties of the members of a shared civil society.”6 Christelle’s predisposition to care for others professionally may therefore be commendable, “Sentimental by nature, Christelle was always sensitive to those who cried out and asked for help,” but her decision to extend this hospitality into the private realm ends up being very much at odds with the broader inhospitable environment in France. This is especially true when one considers, as the novel does, the prevailing actions of the authorities and their representatives, eager to demonstrate their effectiveness at enforcing and protecting a social order that has grown intolerant and suspicious of outsiders and elected to embrace racial profiling, police controls, and ID checks.

From a much longer colonial and postcolonial history—defined by interconnections, neocolonial policies, globalization—two individuals, abandoned, orphaned, unwanted, rejected, and even cursed, somehow find refuge, the courage to risk intimacy. “I was so proud that she’d chosen me,” Nzila shares with the reader. “We were slipping into the craziness of love. Christelle and me, we’d connected. She’d brought me into her universe. Her words gave me hope and enveloped me in an aura of light in the solitary night.” As Karen Lindo has shown, “The physical abandon in which they give themselves over to the pleasures of the body enables the couple to take refuge, however short-lived, from the abuse that has heretofore marked their individual trajectories.”7 However, as Lindo goes on to ask, “Who are the young characters that people N’Sondé’s novels? What are their values and how does this heterogeneous population manifest its sufferings and its aspirations?”8 Nzila has been driven out of his native village, moved up from street urchin to a role in an “army” in which his zealous engagement has provided him for a while with a distorted sense of meaning and even an identity. He may now appear on a Paris commuter train as a frightened, vulnerable migrant, but “I was dragging my disaster along with me like a ball and chain. Impossible for me to turn my back on the past and make that big break and advance toward new possibilities, the hope for a life of stars, happiness.” N’Sondé’s novel therefore provides, through the safe haven Christelle offers, a space in which his story can be recounted, the violent atrocities accounted for and named, such that the process of historical reckoning can begin: “I’d have given anything to forget and for her to never know what I’d really done. Her eyes beseeched me. Couldn’t she simply think about the present and build a future with me? Christelle wanted to know everything, every last detail of that period of my life, the truth. I was asking her to appreciate the new man that she was going to make of me, but the questions were going around in her mouth, in her eyes, kept cascading down!”

N’Sondé demands our presence as readers and listeners, enlists us in the broader process of testimony. How will Christelle react, what is at stake in assuming responsibility, acknowledging transgression, and how will we, as readers, position ourselves? How can a relationship survive confession? What are the limits of empathy, of forgiveness? How does one archive knowledge, restore humanity, and ultimately achieve reconciliation? N’Sondé thus presents us with two societies that continue to struggle with the process of fostering inclusive modes of coexistence, and in which violence and ethnic and identity conflict persist. As Myriam Louviot has argued, N’Sondé’s work confronts the “translinguistic and cultural dimension of postcolonial problems,” and “much could be gained from comparing the writings of authors such as Wilfried N’Sondé with those of other European migrants.”9 Indeed, from his own experiences, N’Sondé has written of how he “realized that the decision to come to Germany had allowed me to finally distance myself from a kind of hexagonal schizophrenia: that of being at once a French citizen whose equal rights were clearly and loudly affirmed but yet whose skin color gave rise to such great rants and ravings that I became increasingly skeptical of what was still being taught at university. Only too accustomed to police checks and the standard disregard for formalities and the patronizing use of the familiar ‘tu’, I quickly had to learn to answer their stupid questions and accept the humiliation if only to avoid a more serious incident. I soon came to realize that this recurrent police harassment was inversely proportionate to the whiteness of one’s complexion.”10 In a country in which the “Frenchness” of non-white individuals has today, once again, become suspect, and the eventuality of stripping “bi-nationals” of their “French” nationality been invoked, Salman Rushdie’s notion of “double unbelonging” has gained additional credence.11

The passage, path, or way to the other requires courage, a sense of adventure, but primarily moral imagination. N’Sondé’s poetic musicality is enchanting but also disquieting, haunting, and unsettling. In the words of the great South African writer Antjie Krog, “To be vulnerable is to be fully human. It’s the only way you can bleed into other people.”12