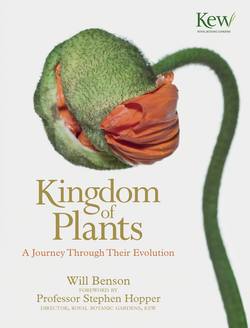

Читать книгу Kingdom of Plants: A Journey Through Their Evolution - Will Benson - Страница 6

Оглавление

© RBG Kew

‘With the spread of plants onto land, their shapes and sizes soon began to diversify.’

In the last five hundred million years, plants have undertaken an epic evolutionary journey that has altered the very make-up of the planet. This journey began in a dark and acidic world and continues today in a world of rich colours, ornate shapes and mesmerising smells.

Every single step of their incredible evolutionary journey has been integral to creating the world we live in today. It is only by pulling apart the threads which create this rich network of flora that we can begin to uncover the extraordinary ways in which plants have come to live and thrive in all environments.

From their humble beginnings plants have become progressively complex and increasingly important to life on Earth. It is only through the success of the plant life on our planet that the animals that walk the Earth can be supported and it is the success of plants that has allowed humans to exist. Ultimately it is plants that will secure a place for our species to exist long into the future.

Blue morpho (Morpho peleides)

Plants today help support vast ecosystems of interconnected species.

© RBG Kew

Over millions of years plants have become increasingly defined and specialised, carving out their own niches on the surface of the planet; each one striving for the evolutionary equivalent of the limelight – a chance to reproduce and spread their genes. In the beginning of the journey we uncover the origins of photosynthesis, an elegant mechanism which revolutionised the way organisms could obtain energy, providing a powerhouse through which plants could grow and compete. In the next step, plants make a crucial leap out of their watery beginnings, as they moved onto the land. But it is from here that the botanical world really came into its own. Plants became tough and tall, developing structural wood that allowed them to reach new heights. They developed mighty anchoring roots and broad, air-pumping canopies. Skipping forward a few hundred million years we meet the rise of the first flowers, signalling the beginning of a great and ground-shaking love affair between insects and plants, setting in motion a course of events that would bind some plants to the animal world. From this point, the pace of the story picks up as we enter the age of rich biodiversity and intricate connections between Earth’s flora and fauna; we discover the extraordinary relationships between plants and animals, and we see that from one form of simple plant, many millions of diverse species have now evolved. And yet the most crucial chapters in the story of plants are still being written

From the early 1800s onwards countless expeditions set off to chart new territory and to collect rare and beautiful botanical specimens with which to fill elaborate glasshouses. This was to be the golden age of plant hunting, and with it began humankind’s fascination with the plant world. Today the spirit of these first pioneers remains in the world’s premier botanical gardens and research institutes. The biologists and ecologists who populate these centres have provided us with a far greater understanding of our planet’s biodiversity than ever before. Ultimately it is these botanists and conservationists who will ensure the survival of the world’s plant species.

* * *

Magnolia sp.

One of the many species that were brought to Europe and are now common.

© Will Benson

To discover the origins of the plant kingdom we have to visit the Earth three billion years ago. At this time a dark gas-filled sky looms ominously overhead, the air is thick and acrid from the smouldering funnels of volcanic activity, and the waters of warm, shallow tropical seas lap at the shores of recently formed magma islands. This is a time we know now as the Archaean eon. In the watery depths of these ancient oceans tiny single-celled organisms drifted through the murky sediments of the seas. These basic microscopic cells were early bacteria, and consisted of nothing more than a simple outer membrane containing just a few primitive proteins inside. Over time, these cells grouped together to form layers of slime across the ancient seabed.

Stromatolites

These fossils in Australia’s Shark Bay represent the earliest known life forms on Earth.

© Minden Pictures/SuperStock

These bacteria survived by absorbing near-infrared light from the sun’s rays that penetrated the ancient atmosphere. This light was used to convert the carbon dioxide and hydrogen-based organic chemicals that they had ingested from the water into sulphates or sulphur, providing them with nutrients. Although this basic chemical conversion may seem simple and insignificant, it was in fact the origin of all plant life we see on our planet today. This chemical conversion is the mechanism which all species of plant and animal on Earth, either directly or indirectly, now use as their ultimate source of energy. This was photosynthesis – the use of the light energy to manufacture vital organic food.

The first photosynthetic bacteria had bundles of light-absorbing pigments enclosed within their cell walls. These pigments were called bacteriochlorophylls, the predecessors of chlorophyll. The ability for these early cells to use energy from the sun to create organic compounds and sugars which could then be used for growth and movement was a major step forward in evolutionary terms. No longer would these Archaean bacteria be confined to absorbing the mere chemical scraps of nutrients available in the sediment. With their gradual radiation throughout the Archaean seas, the bacteria developed and adapted, and over hundreds of millions of years they evolved significantly.

Then, around 2.7 billion years ago, there emerged a further advance in these organisms’ energy-exploiting capabilities. Alongside the early bacteria, new cells appeared – the cyanobacteria. Now while the early bacteria were making use of the ‘invisible’ near-infrared light from the sun, the structure of the pigments in the cyanobacteria’s light-absorbing machinery had evolved to absorb visible light as a means of breaking down chemical compounds to produce food. To help them absorb this visible light even more efficiently they developed a far more varied range of photosynthetic pigments, called phycobilins and carotenoids, as well as several forms of what we know today as chlorophyll.

With the change in the wavelengths of light that these new pigments were able to absorb came a change in the precise chemicals that they could digest. For over 300 million years since the rise of photosynthetic bacteria, the by-product of photosynthesis had been sulphurous gases, but in the case of cyanobacteria the by-product was a simple yet vital molecule – oxygen.

So successful were the oxygen-pumping cyanobacteria in the prehistoric world that great colonies of them, many billions of cells strong, are now found fossilised in the layers of sediment which were laid down during the Archaean and Proterozoic eons. This record of life, captured as it was over two billion years ago, marks a critical juncture in Earth’s history. As the cyanobacteria went about their business absorbing carbon dioxide from the sea and churning out oxygen into the water, some of this oxygen began to make its way up into the atmosphere, where it accumulated in great clouds, many thousands of tonnes in weight. At the same time – and for reasons still not conclusively known – others gases such as hydrogen began to decrease in the atmosphere. Crucially, this reduction in atmospheric hydrogen allowed oxygen to start accumulating.

Liverworts

These may be the closest living relatives to the first plants to live on land.

© Tim Shepherd

Although they are not technically plants themselves, this so-called Great Oxidation Event earns cyanobacteria their place on the plant wall of fame. Oxygen is the third most abundant element in the entire universe, but until the intervention of these simple bacterial cells, Earth’s oxygen atoms were predominantly locked up in chemical relationships with other elements. Elemental oxygen is so chemically reactive that whenever it gets the chance it will bond to nearly any other available molecule, and in the Archaean and Proterozoic eons, there was certainly no shortage of available hydrogen, sulphur and carbon which it could bind to, creating water (H2O), sulphur dioxide (SO2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). But, critically, what cyanobacterial photosynthesis did was to split single oxygen atoms away from water molecules by using energy from sunlight, and then join two lone oxygen atoms together. By forming a partnership with an identical atom, these pairs of oxygen (or O2, as you’ll know them) had alleviated their want to bond to other chemicals through partnering up with one of their own. For the first time oxygen existed in a stable state, and this meant it could begin to increase in the atmosphere.

From the point, two billion years ago, at which cyanobacteria first began to produce significant amounts of oxygen by photosynthesis, it still took a further billion years for the levels of oxygen to reach even half of what they are today. Around 1.6 billion years ago, during the mid-Proterozoic eon, oxygen had risen to comprise about 10 per cent of the Earth’s atmosphere, and by now the cyanobacteria had been joined by a host of varied photosynthesising life. These were the red algae, brown algae and green algae, and for the next 500 million years the soft and slimy, filamentous bodies of these organisms thrived in the oceans of the prehistoric world. As these algae evolved, they increased in complexity, developing advantageous new adaptations. Some developed multiple and specialised cells, allowing them to absorb nutrients and sunlight more effectively, and by dividing labour to different cells their growth and reproduction became more streamlined. Coupled with this, the various different algae packaged their genetic material into a single central nucleus, which distinctly separated them from earlier photosynthetic life. Unlike the cyanobacteria before them, these algae were among the first eukaryotic life forms, made of the type of complex cells that make up all higher life on Earth today. Most importantly, their light-absorbing chlorophyll pigments became stacked and enclosed within a double cell membrane, creating the self-contained photosynthetic structures we know from plants on Earth today. These are called plastids, or when in green algae and plants, chloroplasts. These relatively basic but increasingly ingenious organisms, although still confined to their aquatic habitat, first began to embody what we now recognise as the first plant life on Earth.

The vast colonies of red algae (whose colours actually ranged from green to red to purple to greenish black) stretched across the ocean floor, where they absorbed the shorter wavelengths of light that penetrated the murky depths. Brown algae soon became adapted to rocky coasts, attaching themselves to submerged rocks by structures called holdfasts. Crucially, green algae acquired an advantage that enabled them to thrive in the shallow waters of land formations. Unlike most other algae, green algae (known as Charophyceae) are able to survive, and even flourish, in the strong light of exposed shallows. There are very few fossilised remains of the marine algae of this time, as their bodies were soft and easily broken down when they died. The exact stages that they underwent as they moved closer to land are unknown. However, we can deduce that around 500 million years ago green algae from the marine habitats and freshwater lakes washed ashore and became stranded on land. Some of these would have given rise to the first land plants. The earliest trace of plants on land that is recorded in the geological record is of the reproductive spores of a plant from the Ordovician period, some 470 million years ago. Analysis of these spores has revealed tiny structures which resemble those seen in a type of modern-day primitive plant called a liverwort.

The Palaeozoic era, which literally means the age of ‘ancient life’, stretched from 543 million years ago to 251 million years ago. From this time onwards scientists have been able to trace individual groups of early life. Around 500 million years ago, in a period within the Palaeozoic called the Cambrian, oxygen levels in the oceans dropped drastically, causing a condition called anoxia, which soon spread across the planet. This may have been the trigger for algae to move from water to land. Many of the free-floating, bottom-dwelling organisms in the sea were killed, and this locked away thousands of tonnes of organic matter in their decaying bodies. As a result, the photosynthetic plankton increased in numbers to exploit the space and the nutrients, and they began to pull great quantities of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, in turn releasing large amounts of oxygen. Over a period of a few million years oxygen levels rose from around 10 to 18 per cent, up to as high as 28 per cent. This level has since fluctuated over subsequent geological history, resting today at about 21 percent. So successful were the photosynthetic plankton that they still fill all corners of our oceans today. Just a single drop of water from the top 100 metres of the oceans will contain many thousands of these free-floating organisms. They are still considered to be some of the most important producers of organic matter on Earth.

Marchantia polymorpha

With no internal vascular system, liverworts rely on a moist external habitat.

© Tim Shepherd

Cyanobacteria

These ancient microbes were the first to produce oxygen by photosynthesis.

© Science Photo Library/SuperStock

Bryophyte spore capsules

Even on land these plants require a partially wet environment for reproduction.

© Travel Library Limited/SuperStock

Alongside the oxygen released from the oceans, the first land-based plants further increased the amount of oxygen that accumulated in the atmosphere. When the concentration eventually tipped over the crucial 13 per cent mark, the first wildfires became possible, and sparks caused by rock-slides and lightning set huge areas of the ancient landscape alight. Fossilised bands of these charcoaled plants, 430 million years old, have been found today. With an abundance of oxygen now readily available out of the water, and with competition for space and resources under the water increasing, life on land became a more favourable option. But while their soft, moist bodies were well suited to an aquatic life, the warm, dry air would cause their thin cell walls to quickly desiccate. More so, water was still necessary for their reproduction, in order to combine their male and female gametes.

Over a period of many hundreds of thousands of years, mutations occurred in the cells of some algae which gave them a chance to live further away from the safety of the aquatic environment. A waxy cuticle developed by some algae helped them resist desiccation, and gradually a layer of cells evolved to form a capsule around the embryo to protect it from exposure to the dry air. In time these desiccation-proofed algae reproduced, giving rise to plants better prepared to live out of water. While large blooms of green algae remained water-bound in lakes and oceans, those which had evolved to live for periods outside the water soon began to lose resemblance to their algal ancestors. The bryophytes, as they are now known, became the first land plants on the planet.

Even with their adaptations to terrestrial life, these small green hair-like bryophytes, which we now divide into the mosses, hornworts and liverworts, were still reliant on water, in the form of moisture from swamps and bogs, or dew. As they had only recently left their aquatic environment, in evolutionary terms at least, the bryophytes lacked the ability to carry water and nutrients from the soil to their upper parts, and therefore relied on their bodies to be covered in moisture. Once inside their cells the water had to then pass from cell to cell by the slow process of diffusion. As a result of this, even after 450 million years on Earth, bryophytes have remained small and inconspicuous, confined to the dark, damp habitats. Whereas the lives of their marine ancestors were largely commanded by the ocean currents, the first bryophytes developed primitive root-like structures, allowing them to be anchored to the soil. However, not only were the bryophytes key to all land plants we see today, they are now the third most diverse group of plants, numbering well over 10,000 species on Earth. These plants are closely coupled with many important biological and geological processes, including nutrient cycling in tropical rainforests, as well as playing a crucial role in insulating the arctic permafrost.

If the first major step in the story of plants was the development of photosynthesis, and the second was their establishment on land, then the third crucial stage was the development of their ability to grow from their limp origins, to become tall and tough, and to gain reproductive success over rivals. But from the origins of the early bryophytes some 450 million years ago, plants had to overcome two major obstacles, in order for them to diversify into the shapes and forms that we see today – how to get water and nutrients to all those parts that are not in contact with the soil, and how to support these parts without the buoyancy of water. The solution was found in the tracheophytes, or vascular plants as they are more commonly known.

Silurian landscape

The Silurian period, 444 to 416 million years ago, saw the evolution of the first vascular plants.

© dieKleinert/SuperStock

The evolution of a vascular system was crucial to the plant world. Vascular plants have been the basis of all terrestrial ecology since their arrival on land. Among the first were a group of branching, 10-centimetre-tall plants called Cooksonia, which have been found in the layers of sediment that were laid down during the Silurian period, 444 to 416 million years ago, and are found most commonly today in the fossil fields of the Welsh Borders. Cooksonia had a simple structure, with no leaves or roots, but an internal system of tubes allowing them to move water from beneath the ground up to their photosynthetic structures, and to evenly distribute fuel throughout their branching arms. This hollow internal channel was created by open-ended cells along the length of their stems. In some cells photosynthetic ability was traded in order to take on a purely structural role in the plant. These cells lost their nucleus and their life-giving organs, and instead their walls became thickened with structural sugars, such as cellulose and a tough material called lignin. These vascular plants began to fortify their walls with woody lignin, which gives plants the structure and strength to sprout upwards, unsupported except by their own woody tissues, a key characteristic that separated them from aquatic plants. Over the next 350 million years, the vascular plants would eventually give rise to cycads, ginkgos, ferns, conifers, and ultimately all flowering plants.

By the time vascular plants began to make their mark on land, the story of the origin of plants had already spanned a vast timescale of over 2.5 billion years. Over this period the world had shifted during its fiery volcanic youth, deep in the Archaean eon, its skies became filled with life-giving gases during the Great Oxygenation of the Proterozoic eon, and it had played host to the first endeavours by plants to colonise the land in the Devonian period. By now the world was warm and humid and its surface was dominated by the ancient landmasses of Gondwana and Laurasia. The seas continued to support an increasing array of marine animal life, dominated by filter-feeding bryozoa and a diversity of prehistoric fish, and for the first time animals began to follow in the tracks of plants, and make their way out of the lakes and oceans and onto the land.

With the spread of plants onto land, their shapes and sizes soon began to diversify. By possessing tough lignin-enforced stems that allowed them to counter the force of gravity, vascular plants soon evolved into an array of new and fascinating forms. From the vegetation of the early Devonian, which consisted of small plants no more than a metre high, plants soon began to use their rigid stems to reach new heights. Fossils which have been dated between 407 and 397 million years old show evidence of plants which produced thickened body parts completely separate from their water-carrying internal tubes. These additional structures were the first examples of plants producing bark. As well as the emergence of woody body parts like bark, fossils from the Devonian reveal a whole host of novel structures that emerged at that time, giving this period its name of the ‘Devonian Explosion’. Fossils from this time include plants such as Archaeopteris, which had frond-like leaves, and plants like Drepanophycus, which had metre-long roots that could reach nutrients deep in the soil. These first tree-like plants grew in vast numbers alongside rivers and estuaries and began to give height to the first primitive forests, some growing up to 20 metres tall. Other woody plants from the Devonian include Rhacophyton, which is suggested to be the precursor of the ferns, an 8-metre tree with a large crown called Eospermatopteris, and a plant called Moresnetia which is thought to have been the forerunner to seed plants. The Devonian Explosion also gave rise to many familiar plant species. The 12,000 or so species of ferns that still thrive throughout our Earth’s tropical and temperate zones today bear testament to their early success in the Devonian.

Ginkgo tree

These plants are living fossils, dating back to the Permian period, some 270 million years ago.

© RBG Kew

Animal life was also taking new shape in the warm Devonian climate. Along the damp forest floor millipedes scuttled through the organic mulch, and the first predatory animals, such as trigonotarbids, thought to be relatives of modern spiders, crawled through the undergrowth searching for a meal. In the seas great armoured fish equipped with powerful slicing jaws were quickly increasing in a variety of shapes and sizes, as they evolved to fill the expanding niches of the marine world at the time. In the Late Devonian, around 360 million years ago, the first of these fish made tracks onto land, giving rise to four-legged, air-breathing amphibians, such as Hynerpeton.

The Devonian flora had a fundamental impact on the very nature and substance of the land itself. As the tough, tall forest trees put down their networks of anchoring roots, they began to transform the hard and rocky substrate beneath them into hospitable and nutrient-rich soil. Prior to the plant development of the Devonian, the land surface of the Late Silurian was largely exposed bedrock, near-impenetrable to early root systems. The spread of the land plants of the Early Devonian aided the chemical weathering of rocks, helping break them down and release their mineral nutrients. The plants supplied organic acids from the fungi which colonised their roots, and together with acids given off by the decomposition of plant matter on the top of the substrate, these leached into the rock. This leaching softened the rock, enabling the roots to penetrate further into it, gradually breaking it up into smaller sediments. Over time, as organic matter from the surface was drawn deeper down into the ground, the soil depth progressively increased, allowing it to accommodate longer roots below the ground, and in turn larger trees above ground. As the soils of the Late Devonian and Early Carboniferous progressively deepened and became more developed, plant growth was greatly enhanced.

Archaeopteris

Archaeopteris was one of the first tree-like plants to appear in the Late Devonian.

© Parc national de Miguasha/Steve Deschenes

A world of colour

With the evolution of flowers, the face of the Earth was transformed forever.

© Rob Hollingworth

All of the early plants up until the Middle Devonian possessed male and female gametes which required water, in some form, for their fertilisation. As the original aquatic plants had a totally submerged existence, their sperm cells could freely move through the water to fertilise their ovum cells. This method of fertilisation put some obvious limitations on where they could survive, and out of water their reproductive strategy would have been impossible. Although bryophytes lived on land, they still relied on a partially wet environment to transfer their sperm cells and spores to their female gametes. We know from bryophytes living today, such as mosses, that when their surroundings are saturated some species store up several times their own weight in water as a reserve, and they are also able to stop their metabolism if their habitat dries out for long periods. These water-dependent land plants were therefore best suited to colonise the damp tidal shores of lowland streams of the Devonian forests, and mosses and ferns can still be found to thrive in these environments today. The need of these amphibious plants to be linked to a moist external environment for their reproduction would have been very limiting in all but the dampest of habitats, and so any plant that was able to break this reliance on water would have had an immense advantage. In the drier terrain further from the shoreline there would have been an abundance of space, light and nutrients. Natural selection soon favoured plants with the ability to grow and reproduce in the dry air of these new habitats. Their trick to surviving in dry air was to package up their reproductive cells in desiccation-proof capsules that could carry them through the air. Capsules we know today as pollen.

Equisetopsida

For over 100 million years, horsetails dominated the understorey of the Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian forests, growing up to 30 metres high.

© age fotostock/SuperStock

The first pollen structures that evolved were tiny packages of genetic material, light enough to be carried on the wind to the female cells of a neighbouring plant. On reaching their destination they put out a little tunnel through which their sperm cells could swim down to achieve fertilisation. For the first time, male and female plant structures were able to swap their genetic information over large distances in the dry air. To maximise their dispersing ability many pollen-bearing plants grew taller, and in time the skies filled with airborne DNA from a multitude of pollen-spewing Devonian flora. Although plants would still require water for photosynthesis, it was now possible for them to colonise new, drier regions of the land. From the coastal forests, plants began to push further into the empty expanses of the ancient world.

As pollen plants began to spread their domain further inland, and it became necessary for their gametes to travel over even greater distances to achieve pollination, a further major shake-up occurred in the way in which plants reproduced. This was one of the most dramatic innovations in the evolution of plants on land – the evolution of the seed. The earliest plants which exhibited seed-like structures are known as the progymnosperms, dating back to around 385 million years ago. They included trees like Protopteridium, and the leafy, 10- metre-tall Archaeopteris. The fossils of the trees from this period indicate that some, but not all, possessed structures resembling primitive seeds, suggesting that this was a time when the future of the seed hung in the balance. Like all plants before them, progymnosperms produced spores, but uniquely they were able to produce two separate types – micro-spores and mega-spores. This trait, called heterospory, suggests that progymnosperms were the most likely antecedents of all seed plants. Their ability to create variable spores is thought to have been the crucial intermediate evolutionary stage between plants with free-floating single spores and those with true seeds containing a spore-borne embryo.

The first true seed plants, which descended from the progymnosperms over 350 million years ago, were a group of tree-like ferns called pteridosperms, belonging to the major division of plants called gymnosperms. The word gymnosperm literally means ‘naked seed’, as they produce seeds which are not fully enclosed in an ovary. In earlier seed-less plants, the gametophytes were released outside the parent plant, but in the pteridosperms the gametophytes were microscopic in size and retained inside the reproductive parts of the plant. This created a moist ovule in which fertilisation could take place, in essence creating a plant within the parent plant. Coupled with this, these embryonic packages were encased with some starting-off food, meaning that they could be transported, ready to germinate as soon as they found themselves in the right conditions. The protective packaging of these seeds also enabled them to remain dormant after dispersal, and wait until conditions were perfect to grow. This prevented the precious genetic material contained within from being wasted in times of flooding or drought.

Today seed-bearing plants are the most diverse group of all vascular plants. The evolution of the seed enabled the proliferation of land plants on the wind, in the water, along the ground and in the stomachs of animals. During the Carboniferous and Permian periods, the gymnosperms evolved prolifically, with their extant relatives today including conifers such as pine, spruce and fir, with their needles; ginkgos, with their fleshy seeds; and cycads, with their large palm-like leaves and prominent cones.

Around 300 million years ago a global ice age hit the planet, and the Earth became progressively drier and cooler as great bodies of ice formed at the poles and locked away precious water vapour from the atmosphere. The reduction of atmospheric moisture caused vast areas of tropical forests and swamps to shrink and dry out, and with their ability to disperse their seeds and colonise drier environments, gymnosperms soon replaced ferns as the dominant plants on the planet. In time the higher-altitude regions of the planet became regions of cold-climate peat lands and swamps, which would have resembled something similar to the boreal taiga of modern-day Siberia. In the milder lowlands, deciduous swamp forests were dominated by the seed ferns of Glossopteris and Gangamopteris, along with large clubmosses and immense horsetails.

The first seeds

The development of the seed saw gymnosperms become the dominant plant group between 290 and 145 million years ago.

© imagebroker.net/SuperStock

By the end of the Permian period the main continents of Earth’s land masses had all fused together into one supercontinent called Pangaea, and parts of the planet had become arid with little rainfall, creating extreme desert landscapes. As deserts expanded and coastlines shrank, this extreme climate shift began to push many life forms to the brink, and by 248 million years ago, 95 per cent of the plant and animal species that had evolved by this point were wiped out. This marked the largest extinction ever known, and for the next 500,000 years complex life on Earth teetered on the brink of complete extinction. The 5 per cent of life that remained was sheltered from the extreme climate, in habitats that remained temperate and moist enough. These pockets of life harboured the fundamental DNA that had evolved so far. Over the following 50 million years, as the global climate became more amenable once again, plant life would bounce back to colonise the planet. Slowly plants began again to create temperate woods, tropical forests and dry savannahs.

As the Jurassic swamps and prehistoric woodlands began to spring back to life, plants continued to increase and diversify. Seeds, leaves and pollen became more specialised, and the world of plant life provided an abundance of food for the dinosaurs. Plants gave rise to fast-growing bamboo and shade-giving palms until 140 million years ago, when the plant world would be changed completely.