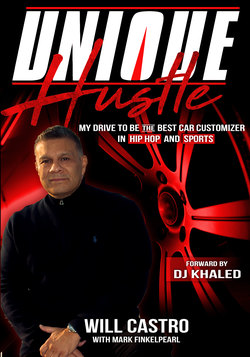

Читать книгу Unique Hustle - Will Castro - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHere’s the thing, you’ve got to have some kind of hustle, some kind of grind, some kind of drive to really survive on the streets of New York. You just have to. If you don’t, it will eat you alive. You’ve got to have grit to make it. Growing up as a kid in 1970s New York City defines me; it was an experience that still reverberates in the man that I am today. I grew up on the Lower East Side, what’s known as the LES for short. I lived in the LaGuardia Houses, thirteen public buildings built in the 1950s and made up of nearly eleven hundred apartments. New York at the time was just like what you see in old movies from the period. I don’t mean comedies like Plaza Suite and Annie Hall. I mean films like Super Fly, Mean Streets, Shaft, Black Gunn, and The French Connection that capture the dirt and the grit and the look and the feel of the city. But it was the people, the characters, that made New York at the time so incredible.

Today, with New York being as expensive as it is, the bohemians, musicians, artists, and dope dealers have moved out. Back then, all the good and all the bad were smashed together. To a large extent, kids like us were on our own, and the city was our backyard and playground. You had to be home for dinner and you had to listen when mom called. But we were free-range kids. Parents did not helicopter the way they do today, and guys like me and my friends were not attached to cell phones all day and night. We could not be tracked, which made for some serious adventures. We were urban, minority Tom Sawyers and Huckleberry Finns and the East River and New York Bay were our Mississippi. We came in contact with all of the good, the bad, and the ugly. And it formed us as people. It was incredible because it was so multicultural; you were immersed in a world of so many different people, so many walks of life. You had Chinatown. You had Little Italy. The Village. You had Katz’s Deli; there was a large Jewish influence from the days of the Ellis Island immigration. By the time the 1950s and ’60s rolled around, the LES was filled with Puerto Ricans (like my family) and folks from the Dominican Republic. You had it all.

That’s New York. And once you’re a New Yorker, you’re always going to be a New Yorker. You know you’re special. I would never give my childhood up for anything. It just was amazing, living down there at that time. It was beautiful. There were rough areas and some bad people, too. An outsider coming into the Lower East Side would feel a little threatened and scared. However, if you were born and raised there, you felt like you were untouchable, because you were so comfortable with the surroundings.

Will Castro on the Lower East Side, circa 1967

In my neighborhood, I went to P.S. 137 and grew up with all sorts of people. There was no racism there. None. We were all from the Lower East Side. We were all minorities. We were from public housing. We were all one, and we all went to the same Boy Scouts, Cub Scouts, PAL football, OLS little league, 10th Street baseball leagues, and 7th Precinct Roadrunners football. (The Roadrunners wore black and gold just like the Pittsburgh Steelers, and that turned us into Steelers fans at a young age just as they were becoming unstoppable Super Bowl champs.)

My father was William Castro, Sr. and my mother is Minerva Capo Castro. They both came from Puerto Rico. My dad was from a tough neighborhood near Old San Juan called Santurce that has the distinction of being the most densely populated neighborhood on the island. My pops influenced me a lot. I always looked up to my dad. He was athletic. Everyone respected him in the neighborhood. My dad was an ambulance driver for a health center, one that still exists to this day in New York. My father was the first person to expose me to a love of cars. He had a hot, red Mustang. It was a ’68, short window, fastback, automatic transmission with a black interior. That car was respected by the neighborhood; everyone knew that was his ride. Besides cars, he got me into the Yankees and took me to ball games on Bat Day.

“My father was the first person to expose me to a love of cars.”

My parents got divorced when I was about seven and my brother Bobby was just a baby. They just could not get along. My dad was a playboy, and he liked to have a good time. He was also hot-tempered: one of my main memories of his red Mustang is not a good one. I must have been about seven years old and my parents had just recently split up. My mother was dating a man named Al at the time. Al and I had been out somewhere, and he brought me back home. As we were pulling up to the building, I saw my father’s red Mustang parked there and it alarmed me. I said to Al “I think that’s my dad’s car, you better just drop me off here,” but Al told me not to worry about it. As we were walking toward the building, my father approached. He said hello to me and told me to go up to the apartment to my mom, he and Al were going to talk for a while. Well, my dad ended up beating him up pretty bad; Al went to the hospital. I’ll never forget it.

I think the bad aspects of my parents’ relationship had an effect on me and my brother down the road, because you try to be a better person, a better father. (I tried to be better in my first marriage with my wife Marilyn and my daughter Paige.) I think that divorce is a bad thing. At the end of the day, it’s the children who are most hurt. So my dad and my mom didn’t see eye to eye, and he wanted to remarry a woman named Naomi. My mom was hurt by that; I know how much she loved him, and it was hard to see her struggle. She became a single parent. She worked hard doing odd jobs to put food on my and Bobby’s plates. Not once did she go on welfare. Her main career was as a dental assistant and later she became a dental supervisor. She was employed by the city of New York and worked for thirty-eight years before she retired and moved to Florida.

My father was still around after the divorce; he lived uptown, in Spanish Harlem. He would pick me up on the weekends. He and Naomi had a steady relationship, and they wound up getting married and having kids together, my brother Chris and my sisters Nayree and Dawn.

Will and his Papi, early 1970s

I did not see my dad every day, but there was a man in my life who was hugely important. That’s my mom’s dad, my Papi. His name was Bonfacio Martinez. Papi was a merchant marine, then he worked at the courts on Chambers Street at city hall. He was very into politics and was always dressed to the nines in a suit, a very proud Puerto Rican. At the courthouse, he was a court officer and file clerk, and he took that job super seriously. He lived with us in the projects, and, every year, he took me to Puerto Rico, connecting me forever to my ancestral home. Papi was there through thick and thin. In my youth, I also developed a faith in God, and I believe God was there too. I’m not really religious, I don’t go to church every Sunday. But I do believe that God acts in my life and I pray, a lot. I’ve needed to!

Through it all, life in the LES was still fun and amazing. My best friend was Kenny Williams, and we were inseparable from grade school through high school. Kenny lived on the second floor, while I lived on the ninth floor at the LaGuardia House. It all began with a fight outside our building. There were bullies all around, and I was a short, small kid. I got bullied a lot, and, because of it, I used to try to duck into the back door of the building to avoid the mess of kids always congregating out front. One time, I was walking in with my mom and said, “Mom, I’ll go around back.”

She said, “What for?” I told her I didn’t mind going to the back door, it was okay. But she soon realized that I was being bullied. And by one kid in particular: Kenny Williams.

Well, my mom decided to call up Kenny’s mother, Hattie, and she said, “Hattie, your son is bullying my son. They’re going to go outside and fight right now, and this is going to end today.”

I said, “Ma, I don’t want to fight. I don’t want to fight.”

She said, “No, your ass is going to go downstairs, and we’re going to settle this, once and for all. You’re not going to be going through no back of the building.”

And sure enough, me and Kenny got into it in the front of the building, and after that we became the best of friends. Inseparable to a point that, years later in adolescence when girlfriends were involved, he would always find a way to mess things up between a girl and me. I write this with a big smile on my face. It’s just that we were blood brothers. We played football together, baseball, bike riding, AFX cars. We were so in competition with one another growing up, it was unbelievable. Boxing, karate—you name it, we did it all.

Will (birthday boy) and Kenny Williams (green shirt)

New York City was our backyard. We had those 1970s bikes with the banana seats (Kenny’s was a Schwinn Orange Krate, and I had the Green Schwinn Sweet Pea. He always had the better bike.) and we’d explore the city on the backs of those. At about eleven years old, I remember getting onto FDR Drive at Grand Street and heading north all the way to the Bronx, like 155th Street. We’d see Yankee Stadium there but we never went to ball games. We’d just eat a cheese sandwich or some snack like that and turn around and head home. It was true adventure. We’d head downtown too, all the way to Battery Park. No parents. The city was wide open to us. We saw a lot. Kenny and I watched the Twin Towers being built; I remember the construction everywhere, putting up these incredible works of art. Later, we’d watch them film King Kong there, and I have clear memories of the giant gorilla lying on its back in the plaza of the World Trade Center, its huge hand facing palm up and wide open. Kenny and I also did crazy stuff like you hear about kids in the 1970s doing. We’d play Evel Knievel with our bikes; we used to make ramps and light fires inside of cans. We would set up three garbage cans, then hurtle all the way from the end of the block and ride up the ramp and jump them. And then we would add a fourth garbage can. Guys always got hurt, man. Some guys couldn’t jump the ramp! They used to do back-flips and all kinds of crazy stuff. In Manhattan, right there in the projects, they have four-foot chain link fences. So kids would build ramps to jump those. We used to do crazy things, just beating up on our bikes. Crazy shit. We used to swing off flagpole ropes. I mean, just this wild stuff that kids would do.

Will Castro riding his bike

We also went to work early. There’s a famous Broadway play called Newsies, and me and Kenny were newsies like that, just 1970s versions. We sold the New York Post, and we said one thing, on repeat: “Get your Post here! Get your Post here!” You had to be aggressive just to make a couple of dollars, but it started one thing in me very young: reading the newspaper. The news of course, but especially the sports section. The back page had the standings, and I started learning about averages and winning percentages and how the Yankees were doing. You know, what’s a “clincher,” when you clinch the title or when you clinch the division. The Yankees were a big part of our New York culture there. Selling newspapers also showed me the joys of making money and having some bills in your pocket.

“Selling newspapers also showed me the joys of making money and having some bills in your pocket.”

This was also a period in time when cars were becoming very important to me, and Kenny had a huge influence on me in that regard. I think if it wasn’t for him, I would not have been into cars. That’s the truth. It began when we were kids, playing with AFX cars, lying down the track and racing. Later on when we got older, Kenny was the first one of us to get a car: a Plymouth Satellite Sebring. I was in love with that car. Kenny brought me around to his uncle’s garage, where he used to park cars, and then I became a valet parker at Mario’s Restaurant. I just did a lot of the things that Kenny used to do. I used to definitely look up to him, like he was a bigger brother, but he was only maybe a year older than me. But this era was later. Once again, I’m getting ahead of the story.