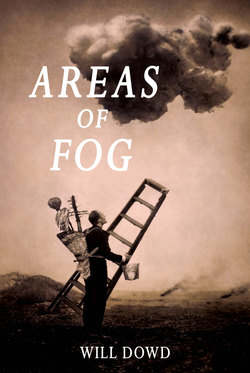

Читать книгу Areas of Fog - Will Dowd - Страница 15

ОглавлениеTHIS WEEK I planned to write about prognostication, a theme suggested (no surprise here) by the punctual reemergence of Punxsutawney Phil, the celebrity rodent who’s been predicting the weather since 1887, though of course it’s not the original Punxsutawney—given the average lifespan of a captive groundhog, Phil has had more incarnations than the Dalai Lama. Then I was going to address the lead-up to Wednesday’s early morning snow bestowal, when dozens of Massachusetts superintendents (a notoriously skeptical order) canceled school before a single flake had fallen. Then I was going to mention the chilling prophecy of my physical therapist (“Snow means shoveling, and shoveling means more business for us”). And then I thought I would discuss the animal tracks I saw Tuesday night (a groundhog’s?) with particular reference to the Dogon medicine men of Mali who divined the future in paw prints left by the desert fox in the sand at night. Finally, I was going to conclude with my own Wednesday morning walk through the superintendent-vindicating snow and how I turned at one point and looked back at the receding trail of my boot prints and wondered what they foretold.

But I don’t want to write about all that. It seems too predictable somehow. Too predetermined.

What I really want to write about are these icicles hanging outside my window—the glittering daggers that would make the perfect murder weapon, if you think about it.

Yet now I have a new problem. Any attempt to describe an icicle sweating in afternoon sun is haunted and taunted by Vladimir Nabokov, who did it better, who did it best:

“I had stopped to watch a family of brilliant icicles drip-dripping from the eaves.… I did not chance to be watching the right icicle when the right drop fell. There was a rhythm, an alternation in the dripping that I found as teasing as a coin trick.”

It’s as if certain features of New England weather are copyrighted by certain writers:

Dickinson has a trademark on that slant of afternoon light.

Frost owns ice-bowed boughs.

And Nabokov has an incontestable claim on melting icicles.

The passage above, by the way, comes from Nabokov’s short story “The Vane Sisters,” in which a French professor in Cambridge, Massachusetts fears he is being haunted, and unconsciously controlled, by the ghosts of two sisters—one a former student, one a former lover.

When the story was rejected by The New Yorker, Nabokov was not pleased.

“I feel that The New Yorker has not understood ‘The Vane Sisters’ at all,” he wrote to the editor. Didn’t she recognize that the first letters of each word in the last paragraph of the story formed an acrostic? “I am really very disappointed that you, such a subtle and loving reader, should not have seen the inner scheme of my story.”

“Subtle and loving”—that’s the kind of reader Nabokov wanted and expected. A reader so enraptured by his prose, so confident in his godlike resourcefulness, so in love with him, in short, that he or she would always be watching the right icicle when the drop fell.

Who needs that kind of love? That level of adoration? I don’t. All I need are these icicles in the window.

Vivid, lucent, antically dripping icicles, menacing iridescent rapiers, yards over us, glinting ominously, towering nobly, oozing tears, hypnotic, imperial, now glowing orange, now melting elegantly.