Читать книгу Red Dog - Willem Anker - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеWe trek through the interior, track the well-worn routes of earlier migrations to the far ends of the Colony. Sometimes the grooves of wagon tracks are clearly visible, sometimes they disappear for days on end and we simply drift from one fountain, spruit or watering hole to the next. We stop as seldom as possible, only when the wagon breaks down or I spot an eland and gallop into the drifting mist on Horse and don’t return without a carcase. Most days drag by monotonously, others begin on a barney and end in bedlam. The baby, still nameless, bobs along on the voyage, wrapped in a kaross, lulled by the creaking and groaning of the wagon never to recall any of it, and laughs and sleeps and cries and for the rest lies there gazing at the wagon tilt that is the limit of her world.

Maria sits on the wagon chest, cracks the whip over the bone-weary beasts and curses them by name as soon as they flag. The Hottentots drive the little herd of cattle, Windvogel for the most part on the back of the ox he got from me as payment the previous year. I sit with Elizabeth in front of me on the horse. She doesn’t sit in the saddle, she finds it too close to another human body. Her little naked body is draped around Horse’s neck. If I touch her to make sure she’s seated securely, that the sun isn’t scorching her, she screams or growls. It’s just she and the horse, but if I tell her the names of animals and plants and stones as we go, she repeats the names in a whisper from within the tangled depths of the horse’s mane. It’s only when she’s on the verge of sleep that she sits by me tugging at my beard, the red furze a forest for her fingers to forage in. Her complexion is not as fair as her father’s, but lighter than Maria’s. The sallow skin and red hair render her an object of open interest to the few passers-by. As soon as they register her grey eyes, they cease their greeting and their blathering and look away and then lift their hats to me and my own grey peepers. At night we sleep in the wagon. On cold evenings the baby lies curled up against the mother-belly as if hankering back to it. When the jackals call in the hills and the hyenas laugh next to the wagon, the red-haired child sits up straight, arms around the knees, watching over us.

From the saddle I survey the bushes and the grasses and the thorn trees and the anthills like towers of Babel. Sometimes I pull up next to a rock formation or a plant that claims my attention, but while there is still sun, the wagon stops for nothing and nobody. I follow the wagon on horseback, my thoughts already straying to other rocks or leaves or wandering off into the distance. I’m not here on a voyage of discovery. I’m on my way to the border. The few people who call this region home have no use for me here: the Christians hunt the likes of them, and they in turn rob and murder the Christians in that old cycle of devastation without beginning or end. Here you keep a low profile and you don’t stay in one place for too long. The Bushmen must never think you want to settle in.

Sometimes we cross the paths of other wagons, sometimes people on foot or on horseback, but nobody makes a lasting impression on anybody else. We don’t outspan at other farmhouses like most people. The customs and the conversations in there are what I’m getting away from. When supplies run low, we sometimes stop over at a kraal. The Hottentots readily barter sheep and edible bulbs and honey, and treat Maria well, this diminutive queen with her gigantic white husband and her Hottentot underlings.

In one kraal of an evening the Hottentots are dancing. When Elizabeth comes to sit by me near the fire, in no time at all there are several figures squatting around her in wonderment. They can see she shies away from human contact. They approach slowly, careful not to startle her. One presses a finger gently against her shoulder. She looks at the finger. He presses an ochre-tipped finger to her nose. She giggles, presses her own finger to the Hottentot’s nose. After a while she allows the enchanted Hottentot to stroke her hair. She climbs onto my lap, but allows them to mark her little body all over with ochre hands like the hands they press against the walls of caves. Eventually the little crowd win her over; she scrambles down from my lap. They lift her onto their shoulders and dance around the fire. She looks like the afterthought of a flame, red and lambent but less so, as if fire had a shadow that could dance with humans without consuming them.

Sometimes I do call at homesteads to angle for news. As the trek wends its way eastward, you need to look ever more closely to identify a hut as Christian turf. Heathens live in round huts; Christian wattle-and-daub huts are rectangular. The news is never good. The Christians I talk to are mainly refugees who abandoned their farms on the eastern frontier and crawled back deep into the embrace of the Colony, only to be robbed and slaughtered here as well. The accounts of these fearful god-fearing folk are as void of meaning as the cairns on graves.

One afternoon one of these gormless Christians crawls out of his mud hut to greet me. A broad-brimmed hat on his head and the tatters of what were once military shoes are the sum total of his apparel. His whole body is peeling with sunburn. He babbles on about Caffres and locusts and his failed crops and this is what he knows and this is his life. How could he know what Omni-Buys knows and what would it be to him that Louis the Sixteenth in this year of our Lord 1785 signs a proclamation declaring that henceforth handkerchiefs must be square?

When the wind blows through the grass or the shadows of clouds tumble over the slopes and kopjes, the whole moribund landscape seems to come to life and race past underfoot. The eye plays games in this endless place where days of trekking feel like standing still, and an hour or so of seeking shelter from a thunderstorm feels like growing old. By day the veldt is dead as dust. We trek past lions lounging under thorn trees, not bothering to bestir themselves for a whole herd of cattle. At the times of transition from night to day and from day to night the veldt is a deafening discord of life calling and cawing and rustling and racing as if aspiring to destinations beyond the multitudinous cycles intersecting here in the softly luminescent spaciousness.

By day I’m never alone with Maria. Our conversations are instructions to each other, schemes to keep the wagon in motion and the children in good health. At night when the offspring are asleep, we can love each other cautiously. If one of the children wakes up from the rocking of the wagon, we lie down giggling between the wheels or steal off into the veldt.

By day it’s just me and the flatness. Usually I ride off away from the team and the wagon, where I can feel the openness and be afraid. On the plain there is nowhere to hide. My chest tightens and the soil binds my feet and pours lead into my veins. I race out over the plain with the thunder rolling and crashing and furious in the black clouds. The lightning bolts set fire to the horizon. There is no hiding place when the heavy drops and the hail start pelting down. It is there that I want to be. That is what scares me. Then I have passed under it and my breast fills with air and my feet become light; then everything is open, in front of and around and in me.

After such a storm the open spaces stir up something in me. I grab Maria from the wagon chest and throw Windvogel the whip, shout a few commands and race into the veldt with my darling wife who is trying to find her seat on the saddle until the wagon shrinks to a spot in the distance. As if the whole world is watching me, I make a great show of every movement. She just happens to be the woman with me; I am strutting my stuff to the veldt. Afterwards I lie against her and drink from her while she strokes my head.

Close your eyes, I tell her. Close them, nobody may see.

I shut my eyes tight and we lie in the darkness and her milk spills into my beard. The team is trundling along slowly, we need not hurry to catch up with it. Back at the wagon the children are crying and Windvogel mocks us until I clout him.

The sun is a lidless eye on the day that the big book with the drawings is found lying on the wagon trail. I read in it: ink sketches of giraffes, the long necks implausibly long, asses, leopards, then horses with rhinoceros horns, water maidens. The further I page, the more freakish the drawings. The lines blur into blotches. On every few pages there are maps in the finest detail and shading repeated over and over again in the book and sometimes scratched out. Every map stranger than the one before. I stuff the book into my saddlebag. I fill my pipe and smoke in the saddle. Before the fill is done, a white wig is lying in the road. Minutes later a black tricorn hat on a walking stick with an ivory knob, planted in the ground. Further along two worn black shoes with shiny buckles, neatly arranged next to each other. Around the next bend a jacket draped over a thorn tree and then some distance along the white shirtsleeves fluttering from a branch. The black velvet culottes we find spread out over a desiccated bush and then a naked man sitting under a waboom next to the road, legs spread, with his head on his chest. The sun-scorched fellow doesn’t look up when he’s hailed and doesn’t stir when I place a skin pouch of water next to him. He pretends to be asleep. I shake him. He snores louder, rolls over and curls up with his hands under his head. I shake again; he draws his head in between his shoulders. I nudge him with a boot. He wriggles his body as if I’m a fly bothering him and snores furiously. The devil take him. I pick up the water pouch and we travel on.

And always, at a distance, the dogs. At night their lamentations and by day they are nowhere to be seen, except the one-eared male who takes up position next to Horse when I lose track of the wagon trail and cut into the veldt. Life and her perils, the miracles and death itself are not to be found on the wagon trail. I don’t go far, I keep my people in sight. Old One-ear pants next to me, his legs less limber than a few years ago. I stand in the stirrups, survey the surrounds. You set yourself up as a target if you don’t check behind the nearest bushes next to the road. Away from the wagon tracks you find signs of life. Other tracks and traces, warm ash in holes where last night small fires were made. A broken rifle, the butt end full of black blood. A man wandering feverishly with vacant eyes, bent under the guilt from which he fled, dying for the water he drank too quickly.

We come across wandering Hottentot families looking for work, who no longer know how to live off the veldt, young people who no longer know the songs of the old. One of the families stops and talks and pleads and the following day I notice them a mile or so behind us. A week later another family following us with little bundles. Everything they have managed to gather on this earth wrapped in hides, cherished close to their meagre bodies. People who are not deterred by shots and curses and threats and eventually trudge along behind the ramshackle ox wagon. Tracks of lion and kudu and dry river beds. Deserted yards with carcases in the dust and skeletons swinging from trees in nooses, the clothes and meat long since redistributed. Burnt-down wattle-and-daub huts, occupied wattle-and-daub houses and huts and shelters that we pass by without entering, especially those where the invitations are too cordial and the eyes have too faraway a gaze and the words wash up against us in feverish stutterings. The solitude of the veldt becomes quite tolerable when you consider the potential danger in any encounter. This land is an open prospect where people burrow into crevices and hollows when they see somebody approaching.

We never see a shadow or a spoor of a Bushman, but at all times we are aware of the little yellow eyes on us and the little fires in the middle of nowhere that burn low every night and the next night a little nearer until one night a few of the creatures come and create havoc among the cattle and we shoot at them. Windvogel wounds one and leaps up from his station and starts crowing about his first Bushman and an arrow lodges itself right next to him in a branch and he pisses himself and starts crying.

We trek past more trees festooned with people like decorations, the rotting flesh, bits of copper on the swinging skeletons reflecting in the sunshine. We trek past lovely mirages. As we trek, the cattle drop dead one after the other, heaven knows why and who’s going to halt to find out, and we trek past trees next to the road of which the bark has been stripped for food or in vengeance or in bloodthirsty delirium and then we’ve crossed the sorry couple of pools the people around here call the Bushman’s River.

So that’s how we end up in the Zuurveld, this expansive battlefield. Zoom up into the heavens with Omni-Buys and survey the Great Fish from above. See how the stream on its way to the sea takes a sharp turn to the east so that for a while it runs along the coast, before it swerves again and debouches into the sea. This right-angled swerve and concurrence with the sea creates a rectangular arena in which various groups of people all at the same time seek to graze their cattle and where between the ocean and the Fish and Bushman’s Rivers they will be clamped and crushed as in a vice measuring fifty by eighty miles. Welcome to the Zuurveld, the land of sour grazing.

The banks of the rivers traversing the Zuurveld are overgrown with trees and thorny shrubs, dense and impenetrable to the uninitiated. As soon as you climb out of the gorges, you find some of the loveliest pastures on God’s earth. This verdant grass is deadly. In summer it offers excellent grazing, but in winter the cattle start dying. The Zuurveld Caffres and the frontier farmers know that in winter you have to move your cattle to the sweet veldt in the gorges that are perennially verdant but cannot support heavy grazing. In summer the cattle move to the sour veldt again. Look, the deckswabs-made-flesh in the Cape draw boundaries on maps in offices. Any cattle farmer could tell them it’s insane, these god-cursed borders that disturb and destroy grazing patterns. The farmers and the Caffres get het up. And by the time I end up here the whole lot is thoroughly pissed off. As soon as my cracked heels step onto my quitrent farm, Brandwacht, my thumbs start pricking like the whole sky crackles before a thunderstorm.

We build a shelter and I go to greet my big brother Johannes. A few weeks later Maria is standing waving me good bye with the baby at her breast. Elizabeth is standing next to her mother and does not wave at me. Accompanied by the few Hottentots who can shoot I venture into the bush. I’m like a child on Horse’s back; I can’t sit still and I babble uncontrollably and order the little troop to go and peer behind every kopje and in every thicket. At night I keep my trap shut next to the fire or I get drunker and louder than anybody else. A week later I return with a herd of Caffre cattle that look a good deal fatter than the few half-dead beasts I drove all the way from De Lange Cloof. I immediately put out of my mind the young Caffre and how he looked at me when I shot him where he was guarding his cattle in the open veldt, that first person I murdered. Later we build a hut and later a proper house. And always, in the distance, the dogs. When we fine-comb the veldt for Caffre cattle, red-brown smudges flash in the corners of our eyes. At night their eyes gleam in the bushes around the house. My Hottentots try hard not to see them. Nobody mentions them, nobody chases them away, nobody takes aim at them; God help the scumbag who dares.

A year later I walk into the wattle-and-daub house. The swallow darts in at the door before me and up to its clay nest under the rafters. We’d hardly moved in or the swallow pair followed and devised their own clay-and-wattle home against the roof. I wanted to clear them out, but Maria insisted that they brought good fortune to any marriage. The little creatures mate for life. I said it’s not as if we were married and Maria said they come and go with the seasons and the rain. Any farmer would thank his lucky stars for a pair of swallows that foretell the weather. The bird-brains twitter all day in their nest but I let them be. They’re not that much worse than the chickens and the suckling pig and the cats and the kids. It’s Maria’s house, I’m not here very often. If she wants to build an ark, it’s her story. The veldt is mine.

The veldt is mine, as it belongs also to my cattle and the Hottentots who look after my cattle and the Caffres who bring their cattle to graze and don’t clear out again. What kind of a Colony is this, where you can’t move your arse at the furthest reaches, as if those who are inside want out and those who are outside want in? And there on the borderline, on the riverbank where the whole lot come face to face, no tribe wants to back down before any other; there’s a chronic butting of heads and a preening like young cocks.

I regularly do my rounds on the other side of the border. No Cape-bred fellow with silk stockings and scented powder in his wig is going to tell me which river I’m not permitted to cross. If the river wants to stop me, the river can stop me, but that is between me and the waters. And the Great Fish is a bugger when it’s in flood. Then that border is a bloody border and you can talk all you like, you’re not going to get across it. But sometimes the Great Fish is no more than a waterhole in a barren riverbank where hippopotami yawn with gruesome teeth. Sometimes it’s narrow and deep, sometimes broad and vague and shallow. Sometimes you can cross by foot. But it is always brown with soil, as if the very sand wanted to get out of the Zuurveld and march down to the sea, the great and eternal boundary where everything flows into everything else and drowns itself and from which all Christians and pen-pushers emanate. In no place and on no day does the eastern border look the same. Nobody steps into the same Fish River twice.

Barely an hour’s trek from where we struck camp this morning, the yellow grass of the plain feels like a long day’s journey away, as if time itself got snagged here in the long thorns that claw and clutch. The water, thick and strong as Maria’s coffee, winds through the kloofs where the thorns grow lush and kudus appear and disappear in tracks that only they can see. In these thickets you could disappear very quickly, for ever if that was what you wanted. To cajole the cattle through this lot is a bloody manoeuvre, even where the water is shallow. There are hiding places aplenty; here everything happens mysteriously. I don’t hear the shell of the tortoise crack under the wagon wheels in the drift, only see the river floating the shards of shell and limbs downstream. This primordial creature that for thousands and thousands of years has been scrabbling unchanged under the indifferent sun. How do I know this? you ask. When I wonder about the soul, I read about vertebrae and magma.

The stream is powerful. It takes what it will. It doesn’t ask before it takes. You have to heed it, even though you don’t heed laws. I frequent the river. I know the river almost as well as the Caffres know it. See, the two groups are standing on opposite banks of the Fish. They don’t look at each other. They are standing on opposite sides of the border watching the border between them coming down in flood and swallowing a sweet thorn and swirling it along and calving a chunk of clay soil into the water. The bartering of cattle and tobacco and copper proceeds without violence. The Christians and the Caffres are wary of each other and joke coarsely among themselves to cover up the tension, but the Hottentots riding with the Christians are taciturn and watch both groups with narrowed eyes.

I pick up words readily as they drop around me. A year or so after my arrival on the border I’m fluent enough to laugh with the Caffres about the Christians who have foreskins and nothing else. If you want to survive here, you buddy up with folks. Farmers of the area who know with whom and how cattle can be bartered. If they turn up on your farm to hear if you want to go and barter cattle with the Caffres, you saddle up and trot along. You must first learn the rules of the game before you can play on your own. Before you can rewrite the rules. Eight or ten armed horsemen are better than one Christian and his gang of Hottentots. This doesn’t mean that you have to strike up bosom friendships. It doesn’t mean that you can’t laugh with the Caffres about the lot on your side of the river. The Christians laugh too, because they see me laughing. I wink at my white pals and I nod at the Caffres.

When both groups have taken from the other what they can and both groups are satisfied that they’ve screwed over the other, they return in opposite directions to their respective wives and children and their just about identical homes of reed and clay.

At home we all sleep next to one another on a pile of hides. The baby is swaddled separately in a hide against the wall. Maria lies in the middle, Elizabeth and I on either side of her, each with the head on one of her breasts. Somewhere in the night Elizabeth crawls over Maria and comes to lie between her parents. The hides don’t cover us properly. I lie awake, uncomfortable with the child half across me. The little body is thin, I feel the skeleton under her skin. I think of how easily the little bones can break. I can’t settle. If I change position, Elizabeth will wake up. Then Maria will wake up. Then all repose will be shattered. I lie dead still and stare at the rush ceiling above me. I listen to the wind buffeting the house, how the rafters gnash and the reed door hammers at the thong tying it down. The wind inhales through every crack and then exhales again in a great sigh as if we’re lying inside an organ of a larger animal of wood and reed and stone. I take one little arm in my hand, lift it up, feel it, the fine frangible bones, the soft flesh, the little hand seeking my hand and clamping a finger. The child huddles up against me, the little head pressed into my stomach, a soft sigh, then a gurgle. Elizabeth has caught a cold. Tomorrow she’ll be ill. The child is weighing down my arm, but I don’t change position. If I were to move now, she’d wake up and start crying and turn around, away from me. She’s never before lain against me like that. Even if to her I’m just a warm object she snuggles up against and even if she doesn’t know what she’s doing, it’s something that must last as long as possible. I don’t move. I listen to the child and watch the little body slowly inhaling and exhaling and now and again twitching in a dream. We lie like that till the sun rises. I get up stiff and sore, and the day begins.

They pay me almost a year’s rent to supply wood for the new extensions in Graaffe Rijnet. In 1787 I borrow a few wagons and load them with yellowwood planks – more than a thousand-five hundred feet of wood – and five Hottentots and two Caffres and trek to the settlement that the Cape periwig-pansies transmogrified a few months ago from farm to town. Word is that they offered one Dirk Coetzee a shit-sack of money for his woebegone farm in a horseshoe bend of the Sundays River and baptised the place Graaffe Rijnet, for the bibulous governor and his wife who between them pour and cram the contents of the Company’s coffers down their gullets.

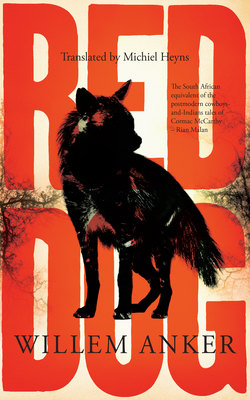

As we travel, the mountains multiply slowly, one calf at a time, like elephants. The dogs turn up the day after I leave Brandwacht. The red dog takes up position by my side and trots next to my horse. The rest of the pack spread out around the wagons, at a distance from the wagon trail, glimpsed only here and there and now and then. The dogs make the Hottentots uneasy. They are used to the phantom dogs that always hover somewhere around me in the veldt, but normally the dogs keep their distance. This trip is different. We are far from home and from any habitation. By the time we outspan, the dogs are around the camp, usually eight or ten of them, sometimes as many as fifteen. They lie around the camp in groups of two or three. A few venture as far as the fire, where the one-ear is lying by my feet. I don’t touch the dog. He doesn’t snool for attention like tame dogs. The dogs gobble up the bones that are thrown in their direction, but for the rest keep their distance. It is as if the dogs are traversing the same territory as us, but in a different sphere. As if they’re moving across the same veldt, but in a different time, and would canter straight through you like ghosts if you didn’t get out of their way in time. A day before we reach Graaffe Rijnet, the dogs disappear: I wake with the first light, tightly wrapped in my kaross. The red dog is lying gazing at me. He trots along next to Horse till late in the morning and then suddenly swerves east and is gone among the low shrubs.

We cross the shallow river, the wagons creaking and screeching over the rock shelves. The trampled strip of soil would seem to be the street; the huts and clay hovels sporadically on either side then presumably the town. Horses stand tethered in front of the houses, here and there smoke drifts out of a chimney, more often out of doors and windows. The geese in the street heave and hiss at the oxen. Some curs trot up to the wagons and try to piss on the turning wheels. One of the thatched roofs is on fire. A few bystanders in the street are watching the inhabitants carrying out their possessions and dousing the roof with buckets of water. I ride past a wagon smith, a carpenter, advertising their trades and skills on the street. After the journey across plains that extend as far as the earth’s warping like rotting wood, it seems as if the town is huddled up against the mountainous mass emerging from the soil like a wall. As if you would sleep more soundly with a mountain at your back. Overripe quinces lie on the ground in front of a scanty hedge. Goats gnaw at everything they see. I ride past what I’m told was once Coetzee’s stable and shed, apparently now the jail and church and school. My wagons have to pull up when a Hottentot drives a herd of oxen along the street, heading out of town. A falcon sits on a roof tearing at a thing with a tail that is still quivering.

I park my wagons next to the drostdy, the converted homestead of the Coetzee family. Part of the thatched roof collapsed with the conversion. Two Hottentots are thatching the roof with reeds. From what I can make out the poor dumb sot Woeke was sent to come and lord it over the wilderness and keep the peace from here to Swellendam. I start undoing the thongs securing the wood. A man walks past in the street. He looks me straight in the eye. He bothers me. His face is long, his beard is trimmed and his hair cut short. He is big, almost as tall as I, but slimmer. His bearing is that of a rich man, even though his clothes are old. Where the material has been scuffed through, it’s been neatly patched. Tears have been darned with a meticulous hand. His shoes are worn but clean. He stops, gazes at the clouds massing around the mountain. His nostrils dilate and contract as he sniffs the air. He nods at me, lifts his hat. I don’t return his nod. He walks on. His footfall is light. Only in antelopes have I seen such ease in a body. He doesn’t look around again. Who does this upstart think he is?

Somebody comes running from the drostdy, a puny little fellow in a too-large uniform, ironed and clean as far as the knees, muddied all the way further down as far as the just about invisible shoes. I regard the fellow. We’re both about twenty-five, but to me the man looks like a child. To the pipsqueak I must, I suppose, look as all the border farmers look to the Cape-coddled powder puffs: bloody-minded, brutish and feral, garbed in leather and hides with the regulation long beard and longer hair. Do you think he wonders where the hair ends and the pelt starts? I square my shoulders and tower over him. I introduce myself.

I ask the soldier who the man is who walked past a moment ago. He says it’s Markus Goossens, the new schoolmaster.

That smug little snob and his little attitude won’t last long on the border, I say.

The soldier looks at the retreating schoolmaster. I ask him where I should dump the wood. The soldier directs me to the back of the buildings where construction is already under way. My workers start unloading the wood. I stoop at a fire, rake out an ember and light my pipe. A tallish man, prematurely bald, with a body soft as a woman’s, comes to stand next to me. He puts his pipe in his mouth and glares at the fire at his feet. He stoops to the flames and staggers. I rake out an ember from the flames for him. The man is neatly dressed, his waistcoat embroidered in more colours than I’ve ever seen on a single piece of cloth.

You’re not from here, I say.

The man tries to talk while clenching his pipe between his teeth. A drooling of slobber dribbles down his chin.

Stellenbosch. I’ve been in the Cape and Stellenbosch all my life.

What does it look like there?

Greener. Mountains. People don’t eat with their hands.

The man laughs. He takes a metal flask from his inside pocket and offers it to me. I swallow the genever. It’s too sweet, but I don’t say no when it’s proffered again. The soldier from earlier fusses around us again. He whispers something in the man’s ear. The man says he’s busy, he can’t be disturbed now. The man taps me on the arm, starts saying something. When the soldier interrupts him again, he turns around too fast. He has to clutch the young man’s shoulder for a moment to keep his balance. In my ear he slurs something about the singular qualities of a Caffre cunt. The whippersnapper clears his throat, embarrassed on behalf of his boss. I accompany both gents into the drostdy. Behold: Landdrost Moritz Hermann Otto Woeke with his arm around the neck of Coenraad de Buys, cackling. I sit the landdrost down in his chair behind his oaken desk and the little soldier ushers me out as quickly and politely as possible, with an extra rix-dollar in my pocket for my loyalty to the Company and their seventeen lousy lordships and my sealed lips.

We pitch camp outside the town. There are plenty of dry thorn trees around to lug together into a makeshift kraal for the oxen. Towards evening fires are lit and my Heathens hunker down, each lost in his own dream. I saddle Horse and ride into town. I ride down the main street and peer into lighted windows and sometimes a hand waves at me. Horse carries me past dark vegetable patches with trailing shadows. When I pull up I hear water dripping from the leaking canal into the parched soil. I’ve heard many stories of the carousing in the Cape, but in this Colonial backwater only the treetops dance in the breeze. I stop a passer-by and ask him if there are women to be found anywhere in this town and the man says Nothing to rent, here you have to marry or buy, Mijnheer, and he laughs and I ride on as far as the last building and turn around and ride down the road again to the other end from which I came. The moon droops low and depleted.

I’ve just galloped past the last house when I see a small group of men walking into the veldt. In the distance I see fires. I follow the men, join them. They don’t talk much among themselves. They walk fast. They say they’re going to watch the fight. Somewhere in the darkness I hear something that could be singing. Who in God’s name would stand serenading the veldt at this hour of the night? We walk in silence until the singing subsides. Then the conversations start up again. A while later a rider trots past, back to town. By his hat I recognise the damn schoolmaster. I ask the men if our master is coming from the fight. They laugh and say No, Master Markus wouldn’t let himself be caught there. I ask them why the piece of misbegotten misery is so uppity. They look at me askance. They say he’s quite a good sort; he simply keeps to himself. I ask them whether it was he who was caterwauling like that in the darkness. They say they don’t know and what business is it of mine.

Arriving at the kraal, we find a few men waiting next to a wagon with animal cages covered with hessian bags. Fires are burning in the corners of the kraal. Twenty or thirty men are dawdling around, laughing and telling jokes, most of them are drunk. Three men are standing to one side where the fire doesn’t reach. Two bull-baiting terriers, seasoned and raddled fighters, and a massive German mastiff. They are standing well apart from each other. As soon as the dogs come within range, they leap and snap at each other. A man with bandy legs and long arms summons two Caffres. They lift one of the cages from the wagon, haul it over the kraal wall and place it in the middle of the kraal next to an iron pole hammered into the ground. The bandy-legged man drags a chain from the depths of the cage and locks the chain to the pole. One Caffre stays behind in the shallow pit of scuffed mud and straw and sawdust. There’s a shout and suddenly everybody presses up to the kraal wall. The men jostle each other to have a better view. The Caffre rattles the bars of the cage and something grunts and bumps in there. The faces around the kraal seem bizarrely distorted and inhuman in the shadows of the flames. I see the smith and the owner of the inn in his absurd velvet suit and farmers and builders and everybody laughs and drinks and gobs. Somebody tosses the Caffre a spade. He picks up the spade and scrambles onto the cage and knocks out the peg locking the cage and jumps from the cage and swears in his language and runs to the wall. The men jeer at him and nothing happens. Then a big baboon comes walking out of the cage with a chain around its neck. He runs as far as the chain permits, the chain tightens, jerks at his neck and pulls him off his feet. He falls on his arse and the men guffaw and gob. A man with new shoes climbs onto the wall and walks all around it waving his arms and his hat and asking for bets. As soon as his hat is full, he climbs down. As if this were a signal, the men with the dogs climb over the wall. They release the three dogs. The dogs charge the baboon. Creatures human and animal go berserk and blood flows. From the direction of the wagon other shrieks from the throats of what could be baboon and leopard and hyena and jackal and other animals that no human has contemplated for long enough to name.

The baboon utters a hoarse bark, fights furiously until it sees the dogs are drawing strength from its fury. It goes onto its hind legs, extends its arms to the younger of the terriers and screams. The dog charges at the baboon, leaps aside and feints and leaps again. The dog’s fur is marked with the scars of previous bouts. He won each encounter because see, he’s alive. The dogs shiver and yelp, but keep a wary eye on the length of the chain, stay out of reach of the baboon. See the dogs dancing around the baboon. One goes straight for the baboon, then jumps back from the fangs. If they can’t get hold of the baboon, they snarl and snap at each other.

The baboon has been fighting in the veldt from infancy, because see, he too is still alive. When a dog comes close, he jumps up in the air, but the curs are clever enough not to be trapped under him. Sometimes a sudden cuff with the arms, or a more surprising grab with the back legs. The ape tightens its circle, the chain slack enough for a leap. The dogs know these monkey tricks. See, they’re tiring him out.

In the kraal there are no orderly formations; the fatal circle becomes a universe where soil and skin and straw and teeth and hair and blood blend into new terrifying creatures that suck everything around them into a sinkhole. Surprise attacks, then moments that expand into ghastly silences before the teeth find one another once more. The baboon rips open the mastiff’s throat, chucks it aside with a human hand, the graceful animal instantly a limp heap of skin and meat.

The terriers charge when the baboon tries to climb up the pole. The biggest dog gets hold of the ape’s hind quarters and rips him open from below. The baboon’s hands let go and the other dog is on top of him and digs into the innards and tugs at the guts. The ape is hanging between the throttling chain and the dogs that each has hold of a length of gut. The gaze and the screams of the baboon, like those of somebody on a rack, floundering between forces tearing him apart from three directions, are unbearably human.

A man vomits and his friends laugh and gob. Somebody bumps into me and I look around into the beggar’s face and he looks away.

The baboon grabs the nearest dog and brings the animal’s face up to its own. Do they know how much they look like each other? With the ravishing jaws that decorate many a farmhouse, it tears off the face of the fighting dog, who until recently resembled the proto-wolf from which all dogs are descended.

I rub my thumbs and index fingers together until I can feel a static crackling. The remaining dog keeps tugging at the guts. The baboon curls up against the carcase next to him and there is a tremor in one hand and something like a yawn and I see something in his eyes and then he is dead.

Money is exchanged; the panting young terrier’s tongue is hanging out. He tries to shake off the blood. He stamps his paws. His ears are drawn back. His eyes dart to those of his owner and then to the baboon. His owner puts on the chain and takes him home. The two Caffres throw the dead animals over the wall and bury them. I stand watching until the kraal is deserted. Young men my own age try offering me spirits, try telling me about the most accommodating girl in Graaffe Rijnet, try talking about anything else.

I ride back to our camp and find Windvogel and Gert Coetzee the half-caste Hottentot by the last embers of the campfire. They don’t talk, each thinking his own things.

A star shoots across the length of the Milky Way. I see the wonderment of the two men.

God has chucked out his old milk again, I say. It’s beneath him to drink clabbered milk. He only scoffs sacrificial lamb.

Master mustn’t blaspheme like that, says Gert.

Some or other preacher put all sorts of things into the Hottentot’s head. Gert has never been able to tell me who the man was, one of the wandering prophets criss-crossing De Lange Cloof in donkey carts hoping to come across lost souls. According to Gert the man’s name is Master and when I ask Master who, then the reply is Master Master, Master.

That’s the backbone of the night, up there, says Windvogel. It keeps the sky up in the sky.

That’s no bone, it’s the Lord bringing light to our dark land.

Oh, bugger off, Gert!

You don’t know the Lord, Vogel. I shall smite thee by God! Ishall devour thee by God!

How do you know the Lord, Gert? I ask.

Master told me about him. We were all in the garden together, don’t you know, and then we had to get out and then everything got buggered up.

And when were you in that garden, Gert?

No, Master, don’t you know, it was before Jan Rietbok came to plant vegetables here.

And then you had to get out of Eden?

Yes, Master. And then the flood came, don’t you know. And everybody drowns and we sail that ark.

Gert is silent for a minute, lost in thought.

I still remember that pigeon.

I start spluttering. Windvogel erupts in a fit of laughter implausibly violent in a body as thin as his.

What’s Master laughing for, and you, you good-for-nothing Bushman?

It’s quite a story, Gert. Master Master taught you well, I placate him.

Master thinks it’s all just stories. What does Master believe?

The Caffres say that smear of stars is the hair bristling on the back of a fierce dog, I say.

Does Master believe it?

That as well, yes. Come on, you must get some sleep, we’re moving on tomorrow.

The two men walk off, jostling each other, to where they made their bed under the wagon. I remain sitting. Later I add more wood to the fire and watch the dry wood surrendering to the reborn flames.

The next morning the men start loading the wagons. I walk off into the veldt. In the distance I see a dog-like creature darting from a bush. It could be a wild dog, or a jackal caught short by the sun. The animal is far away, all I can see is the red-brown stain skimming over the level ground. The creature is on its way somewhere, or simply gone. I watch the animal becoming a piece of running grassland, how it disappears into the grass and then leaps out from the brushwood again. As if it’s playing. As if there’s enough velocity to allow for play as well. As if velocity is itself a game not needing anything else.

I walk on, the wagons get smaller and disappear.

I clamber on top of a large anthill. I look around me. It is grassland as far as I can see, in front of me as far as the Graaffe Rijnet mountains; behind and next to me the flatness stretches as far as the eye seeks a point to focus on and finds nothing. The horizon is not a point, it’s where everything perishes. I look around me:

Red dog!

Then as loudly as I can:

Red dog!

I look all around me.

Later I climb down and walk back to the camp. Windvogel sees me and comes running to meet me.

Buys, where have you been? he shouts.

He comes to stand in front of me, out of breath, hands on the knees.

We’ve done packing. The men are waiting just for you.

You must stop calling me Buys when the others can hear. They think you’re trying for white.

Yes, Master, he says mock-deferentially.

Bugger off, man. Tell that lot to have done and start moving on. I’ll catch up with you tomorrow.

As you say, Master.

I’ll thrash the hell out of you, you cheeky Bushman, I shout and take off and chase my only friend on earth through the scrub back to the wagons.

In the camp I think my thoughts and the lot leave me alone. I saddle Horse, roll up a hide blanket behind the saddle, fill my powder horn, throw a few lead pellets into my jacket pocket and take my rifle. I also take one of the Hottentots’ rifles and a Caffre’s short assegai. I push the extra rifle and assegai into the rolled-up kaross. Windvogel fusses around me again.

Do you need a hand?

You stay with them, see that the lot keep to the road.

What are you going to do?

Make trouble.

I ride back to Graaffe Rijnet. The people out and about talk about the Bushmen who are attacking families at Bruyntjeshoogte and the commandos that are useless and aren’t shooting enough of the creatures. People talk about the rain that no longer listens to prayers. People tell how a crow pecked out the eyes of a baby the previous week. The veldt is empty and dry and soft flesh is scarce.

When the moon is drifting discarded in the sky like a dented tin plate, I lie in wait at the kraal for the men and their dogs and the doomed zoo on the wagon. It is weekend, there are more people here tonight. The wagon with the cages comes trundling along. Tonight’s dogs are standing in wait already. The young bull terrier is back, its wounds not yet healed. Its comrades for the evening a greyhound and a mongrel, a solid chunky animal without a tail and the eyes of a true believer. There are four cages on the wagon. They lift one of the cages down and open it for a large hyena with an outsized muzzle over its snout. The hyena is calm, used to people. It’s also been here before.

The men howl at the moon like ruttish backyard curs. The wind is keen and bleak; the only cloud in the sky is covering the moon’s shame. The two Caffres drag the hyena on its chain over the low stone wall, the hind legs dig in on this side until the neck can take no more and the animal stumbles over into the pit. The Caffre removing the muzzle gets nipped and the men roar with laughter.

Outside the kraal the dogs are barking more loudly. The hyena shrinks back into itself and tugs at the chain. A drunk stumbles over the wall and staggers and kicks at the hyena and turns around to the onlookers with his hands in the air and laughs. Behind him the animal leaps forward until it’s checked by the chain, just short of the drunken sot’s mug. The man gets a fright and his friends laugh at him and gob. I walk up to the wagon. With the short assegai I aim lightning-fast jabs at the soft pelts in the three cages until all sound ceases. I drop the wet assegai and walk in among the crowd with the two rifles over my shoulders and nobody looks at me and to everybody I’m just another face with something in the eyes and a clenched mouth that has something to bite back.

The hyena trots along the circle circumscribed by the length of the chain, then hunkers down next to the iron pipe. It looks at the people, then at the dogs and then at the fires. It lies down. It gets up when the dogs scramble over the wall after their handlers. The chains are slipped off; they make for the hyena. The hyena barks and howls from the depth of its throat. They snap and bark and embrace each other on their hind legs with the front paws around each other’s necks. The open mouths seek each other out like those of hungry lovers. The greyhound grabs hold of the hyena by the snout. The hyena shrugs itself free and bites the dog across the back with the mongrel also already upon him from behind. He shakes the mongrel off and bites. The bull terrier is keeping to the sidelines, still sated with last night’s blood. The hyena pins the greyhound to the ground and bites at the throat and misses and bites again and adjusts its grip and bites deeper.

Somebody asks me about the hyena in the middle.

It’s not my hyena.

The man looks confused, asks me how much I’ve got on the hyena. I say I did not bet anything.

On whose side are you? the man asks.

A windbag with a sack for a shirt scolds and hisses and apes the fight in a farcical mime. When the hyena pounces he and a henchman grab each other in the same grip as that in which the hyena and the dogs are tearing at each other. His mouth gapes open when the hyena barks, his teeth gnash when the dogs growl, as if he’s the puppet and the dogs the ventriloquists.

The hyena retreats, its mouth stretched open, a sharp yelping. The dogs circle. The hyena leaps, first at one dog, then the other. The greyhound lies bleeding. The bull terrier has an open gash across the back, the mongrel’s snout is in shreds. The hyena is red all over except for the white sinew dangling from its paw. The animals fight without surrender, as if they’ve fought and died a thousand times in other bodies in other arenas.

The men around the kraal are now talking more to each other, bored with the bloodbath. They’re staying for the bets, but the fervour has dissipated.

The firelight finds the hyena’s eyes. I once again see the same thing I saw in the baboon. A pure thing, something that I have only seen this close up in animals in traps.

I make my way through the wall of shoulders, firmly push aside those who don’t give way. The mongrel is in tatters and has no chance any more but does not stop charging. Its owner climbs over the wall, tries to get the chain on his dog again. The dog bites him and the man curses and his friends echo his curse raucously. I look at the men on the other side of the kraal, some of them with spatters of the fight on their faces. They shout and bark and gob and wipe the blood from their eyes and how can they not see it? I step back, suddenly afraid that the hyena’s chain will snap, and then I hope the chain will snap and I smile and then I’ve already swung the one flintlock from my shoulder and aimed it at the hyena and pulled the trigger. The powder ignites and while I have to keep the rifle aimed at the target for an eternity while the powder burns and launches the bullet out of the barrel, the men around me all of a sudden stand struck sober and stupid. The hyena crashes down. I already have the second rifle in the foul face of the drunken lout next to me and I open up a passage through the crowd and have to smack one pipsqueak with the butt of the rifle and then I’m on my horse and gone.

Some distance along I hear somebody calling after me. A rider follows me and shouts about the value of the hides and how much I owe him and you can’t just shoot another man’s animals. I gallop on and the man carries on shouting after me, but never tries to catch up with me. A few hundred yards along he adjusts his pace to mine. He hollers until his voice is raw and the words are mere sounds and the shouting just a shouting and he gives up and turns back to his pals.

At daybreak I wait for the men to wake up while I boil water. We travel back to Brandwacht. I sit silent in my saddle and wonder why wagon trails always wind even though everything is flat and straight in front of you and nobody asks me any questions but they talk among themselves.

On the second day out of Graaffe Rijnet we notice the dogs in the underbrush again. A red one trots out in front of Horse. It’s not the one-eared dog that I wrestled. This one has a fresh mark across the snout; both ears are erect. He is broader and darker and younger than old One-ear, his eyes wilder. The pack leader is dead, long live the pack. What happened to old One-ear? Tick bite? Old age? Did he have to defend his position with his teeth and was he too old? Was he bitten to death or did he wander into the wilderness, a defeated loner? Life surges on, the pack lives for ever. The dogs have a new captain and I have a new shadow.

At home I bustle to and fro around the place and at night I lie awake. Maria manages after a few days to drag the story out of me.

And so they let you go just like that?

They wouldn’t shoot a man for a hyena and a few apes.

You know they shoot for far less.

How must I know why they didn’t shoot me.

You were angling for it.

I went back for the animals on that wagon. I knew I was going to blast the daylights out of whatever was let loose in that kraal.

Oh come on, Buys, I know you. You also wanted to see what they would do to you. The Graaffe Rijnet boys.

I’m silent.

You didn’t shoot the dogs?

What for? They’d been tamed already.

In winter when the river can hardly flush away your piss, my comrades and I and our Hottentots trek through the bushes and kloofs and river to Caffreland and return with cattle from the Mbalu kraals. A few nights later Langa’s people trek through the bushes and kloofs and river and get away with cattle from my kraal. A few days later I trek through the bush-grown kloofs and the dry river and return with Langa’s cattle, and a few days later Langa treks through the overgrown kloofs and the Great Fish River and returns with my cattle. Langa is eighty and he’s always fought and he’ll always carry on fighting.

When I come home on a strange horse with a herd of strange cattle and a wagonload of ivory, buck hanging from the wagon tilt, and guns – chests full of smuggled guns – Maria comes running out of the house and she takes up position a few paces in front of me and I walk up to her and she steps back and stops when I stop and looks down and closes her hands tightly over her thumbs and presses her hands to her sides and looks up quickly:

Your child is dead, she says.

The baby was buried behind the house against a hill, a heap of stones piled on top of her little carcase. Maria takes me to the heap of stones. I have still not said a word.

You couldn’t have waited? I say.

How was I to know when you’d be coming home? You’re forever drifting about.

I am silent. I sit down and pick up one of the stones. I stroke it, knock it against another stone.

I should have waited with the burial, she says. But I didn’t think you’d mind. You were gone. It was starting to stink.

That’s all right, I say. It wouldn’t have been of any use.

I wait for the afternoon to heat up properly. I go and chop wood and ride a distance on my new horse that does not yet recognise my body’s signals. The following morning I’m awake before sunrise. I walk up to the hill with a pickaxe. I hew rocks from the incline that one day when we’ve all copped it will become a mountain. I take out the rocks and split them further until I can pick them up. When my people come and ask whether they can help me I chase them away. I carry the rocks to the heap and pile them on my daughter’s body.

After a week the pile is higher than the house and wider. Maria comes to stand before me with her arms akimbo.

You never even gave her a name. You never touched her. She was nothing to you.

Now she’s become something.

She wasn’t a heap of stones.

I can touch the stones.

In the course of the next few days I spend less and less time with the stones. The new horse is clever. The person from whom the Caffres took him, whoever he was, had taught the animal things that other horses don’t know. The horse is big and dappled, and when he runs, the speckles blend into a snowy nightmare bearing down on you. My flame-haired Elizabeth can’t keep her eyes off the massive animal that runs so fast. It looks as if his hoofs don’t touch the ground, as if he’s going to slide into the air and rend it apart. She draws a picture of the horse in the sand and shows it to me. The horse has eight legs. She names him Glider and I call him, for her sake and despite my aversion to animal names, Glider. I teach my daughter to ride the horse. I teach the horse subtle signals that others won’t notice. I teach the horse to pick up its hooves all the way under its chin and put them down thunderously as the Frenchman’s horse did, but with more fury.

In these days it comes to pass that a couple of cattle disappear every now and then. When the herdsmen come to complain, I tell them to shoot when they see Caffres wandering around where they have no business to be. I hand out guns. When the number of missing cattle on my farm increases to about twenty, Coenraad Bezuidenhout turns up on my turf. I’ve heard stories about this farmer, one of the most notorious in the district. I offer him a bowl of coffee. He says, Pleased to meet you, we must join forces against the Caffres. He’s heard I can shoot like no Christian in these parts and that my horse can outrun an assegai. He says talents like that should not be hidden under a bushel. Bezuidenhout and I and a few armed Hottentots set out for the Caffre kraals and return a week or so later with more cattle than were missing.

Elizabeth talks to me about the horse. I’m allowed to lift her onto the horse. In the evenings I go to add more rocks to the pile until one evening I start chucking them down. I climb onto the pile and look around me and then I start breaking down the pile. When all the rocks are lying about around me, I call two Hottentots and order them to cart off the rocks so that nobody will ever see that there used to be a pile here. I leave only the few stones of Maria’s little heap. I walk into the house that evening. Maria is a few weeks pregnant and is salting biltong.

May I ask? she asks.

What for?

That night the little woman holds me tight and strokes my head and slowly rubs me hard. I mount her and she touches me gently and tenderly and that infuriates me. She becomes aware that I’m trying to hurt her; she goes quiet. Later we lie together, careful not to touch each other, like two wounded animals.

It’s in that year or the next that Gert-who-remembers-the-pigeon absconds. Just check in the Colony’s documentation how the baptised bastard-Hotnot Gerrit Coetzee starts tattling. Read there how the scoundrel in 1793 declares on oath that I, on pretence of hunting elephants, cross the Fish River to the Caffres and rob them of their cattle, as many as I see fit. According to the declaration, I drive the cattle to my farm and if the Caffres object I make them lie on the ground and then I flog them with whips or sticks or whatever. The bastard of a convert declares further that in the course of one such incident I allegedly instructed the Hottentots Platje and Piqeur to fire on the Caffres. The first-named killed five and the last-named four. To this the reborn Hotnot then adds a declaration from Platje that testifies to my so-called mistreatment of my goddam farm labourers.

Look me in the eye and ask me straight out and I won’t deny any of this. Why should I? I listen to these accusations and I nod. I don’t know and don’t care a damn where he digs up these stories, but don’t tell me that that god-cursed lump of typhoid-turd called Gert ever went along on these raids. That Hotnot couldn’t have hit his own misbegotten foot at close range. I would never have taken him along. He was there about as much as he ever played with Noah’s pigeon.

On 21 March 1788 I receive a letter from my uncle:

My heartily commended nephew Coenraad de Buys

I have to inform you that Langa has let you know he demands payment from your good self for beating his Caffre, otherwise he will immediately attack afresh. He considers it a challenge to himself and the Christians must not think that he is scared of waging war.

With greetings from us all.

I remain your uncle,

Petrus de Buys.

I don’t receive many letters and I save the letter and read it again and again. While I’m reading it, my fingertips tingle.